In 1935, Korunk [Our Time], the left-wing literary journal of the Hungarian community living in Transylvania, published a long exposé on the works by French writer, André Malraux. According to the author of the essay, Malraux presents “the real drama of the colonies, while he also introduces the grave experience of a continental turmoil into the imaginative rebellion of literary youth.” Beside the novel La Condition humaine, [Man’s Fate, 1933], the article also mentioned Malraux’s latest work, Le Temps du mépris [The Days of Wrath, 1935], in which he tells a story of the underground resistance to the Nazis within Hitler’s Germany. “This story (which is based on the trip to Germany that he made to save Dimitrov), is a monologue of the distressed individual with a deep experience of prison; within and above him is the desire to sacrifice himself and struggle for solidarity.” Malraux was among those left-wing French intellectuals who formed the Association des Écrivains et Artistes Révolutionnaires [AEAR – Association of Revolutionary Artists and Writers], an organization set up to fight against Fascism and for “the Defense of Culture.” Anti-Fascism became the common ground on which the Popular Front governments of France and Spain could emerge in 1936, despite the ideological differences of their respective constituent entities. In a country like Hungary, where the so-called Hazafias Népfront [Patriotic People’s Front] was active during the Communist regime, the notions of anti-Fascism and the Popular Front are considered as part of a larger scheme of Communist propaganda, and figures like André Malraux are held as truthful followers of a Stalinist agenda. As much as the Popular Front idea gained from the resolutions of the 7th Congress of the Communist International (Comintern) in 1935, European intelligentsia was striving for a united front of left-wing parties and organizations long before the official Communist policies changed in this direction. The growing tensions in European politics, as well as the threat of the rapid spread of Fascist and Nazi ideas in almost all countries of Europe, warned many intellectuals that the conflict between left-wing parties was futile and dangerous. Attila József was among these intellectuals who pleaded the importance of a united front. However, he was heavily criticized because of the political essay Az egységfront körül [On the United Front, 1933] by the narrow-minded Muscovite leaders of the Hungarian Communist Party (KMP), which was a consequence of his leaving the Party. And despite Malraux’s evident Marxist sympathies and his bitter criticisms of Fascism, Le Temps du mépris was the only one of his books that was allowed to be published inside the Soviet Union.

In fact, anti-Fascism began where Fascism began, in Italy, with the Arditi del Popolo [“The People’s Daring Ones”] who famously swam across the Piave River with daggers in their teeth. The Arditi del Popolo brought together unionists, anarchists, socialists, communists, republicans and former army officers. From the outset, anti-Fascists began to build bridges where traditional political groups saw walls. While the German Roter Frontkämpferbund [RFB, Red Front Fighters’ League], (which from 1932 became known as Antifaschistische Aktion, or “antifa” for short), was indeed the paramilitary organization of the German Communist Party [KPD, Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands], the famous clenched-fist salute they began to use was picked up as a universal symbol of the fight against intolerance, and was used by anarchists, radicals, civil right activists and all kinds of organizations alike throughout the 20th and 21st century. The symbol of the clenched fist was also adopted by the Popular Front government of France and by the Republican fighters of the Spanish Civil War. Furthermore, it became the logo of the left-wing Artists’ Union in the United States. The language of anti-Fascism was just as universal as the language of Fascism, and it connected all kinds of intellectuals from the political spectrum of the Left.

Some historians have emphasized the prior loyalty of Communist supporters of the Popular Front to the Stalinist regime in the USSR, and have explained their new-found faith in democracy as, indeed, a mere “tactical camouflage” (a view given retrospective weight by the 1939 Nazi–Soviet Pact). Conversely, some historians have chosen to see in the militancy of rank-and-file supporters of the Popular Fronts, and in the volunteers who went to fight with the International Brigades in the Spanish Civil War, the manifestation of a genuine passion for democracy that had its roots in a tradition of popular radicalism. For Stalin, the French Front Populaire or the Spanish Civil War were indeed only testing grounds for how to turn popular democracies into Communist dictatorships in Europe, or in the regions where his hand would reach. Yet, the majority of the left-wing artists and writers who supported the cause of a united front against Fascism—like Malraux, Bertolt Brecht, Antonio Machado, or Attila József—also had their doubts about the Stalinist system, and, with few exceptions, they were even less inclined to follow the Stalinist aesthetic of Socialist Realism. On the grounds of an “anti-Fascist minimum”, they were more concerned about the enormous social inequalities, which were amplified by the Great Depression, and the severe political tensions in their respective countries.

Bertolt Brecht set out in 1935 on his first voyage to America. He sailed on a grubby, if not black, freighter, from Denmark, where he had spent several years in exile from Hitler’s Germany. His destination was New York and the opportunity to collaborate in a production of the “Lehrstück” [“play for learning”] Die Mutter [The Mother], which was based on the novel by Maxim Gorky, at the Theater Union. The production, however, did not go according to Brecht’s plans, because the ensemble was not open to his concept of an “Epic theater”, and Brecht returned to Europe with a bitter taste in his mouth. The same year, he attended as an exiled German writer the First International Congress of Writers for the Defense of Culture at the Palais de Mutualité in Paris. The Congress was a rallying point for European intelligentsia in the fight against Fascism, and the literary world’s response to the slogan of the “Popular Front”, which was heralded during the 7th Congress of the Communist International. Despite the defining influence of the Soviet delegates and other Communist writers, it was the first congress in history where the notion of cultural freedom and the danger of totalitarianism were so widely debated. In reality, the desire for unity among left-wing organizations preceded the Comintern’s new policy, and it was based on the fact that Fascist and Nazi ideas spread rapidly in almost all countries of Europe and beyond. It was also based on the fear of a new war which, by the mid-1930s, seemed closer than ever. The rearmament of the Germans—in spite of the resolutions of the Treaty of Versailles—as well as Italy’s war in Abyssinia clearly showed that the highly complex alliances and pacts between the powers of Europe would not guarantee peace.

Brecht fled from the war in 1941 to the United States. Along with the exiles fleeing from the Nazi regime, the ideological battles of Europe also reached America. The 1930s was a period of massive pro-working-class social reforms and of a mass socialist presence among working people in the United States. The New Deal policy of the Roosevelt government did not only manifest in different federal agencies that tried to improve the lives of people suffering under the Great Depression and the ecological catastrophe of the Dust Bowl. It also set up various programs to provide work relief for artists in various media, and it also commissioned artists to document the hardships of the Americans during the Great Depression. The artists also formed unions and other organizations to fight for their rights and for artistic freedom, and many of them also joined the fight against Fascism.

After the Second World War, in the years of the Cold War and “Red Scare”, Brecht was summoned to appear in front of the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) in 1947. Much to the surprise of the HUAC, Brecht had never been a member of the Communist Party. He was exposed not as a Communist, but rather as a curiously elusive writer and critic who had championed the right to aesthetic freedom and political dissent throughout his career. His aesthetic legacy is perhaps best represented in the conclusion to the statement that he presented during his hearings, which in no uncertain terms defends the necessity of art for the cause of freedom: “My activities, even those against Hitler, have always been purely literary activities of a strictly independent nature… I feel free for the first time to say a few words about American matters: looking back at my experiences as a playwright and a poet in the Europe of the last two decades, I wish to say that the great American people would lose much and risk much if they allowed anybody to restrict the free competition of ideas in cultural fields, or to interfere with art, which must be free in order to be art.”

Like other popular fronts of the interwar years, (such as those in Germany, Chile, and Spain), in France Le Front Populaire [The Popular Front] was formed in response to the imminent threat of a Fascist takeover of the national government. Socialists, Communists, and other left-wing parties deferred their disagreements and mobilized as an anti-fascist coalition. Triggering the mobilization in France were the riots of February 1934, which followed scandalous revelations of government corruption. The movement against Fascism peaked in May 1936 with the leftist victory in the national elections, which brought into power the Popular Front government of Léon Blum, whose mandate lasted for just over a year, expiring in June 1937. The Popular Front was an alliance of left-wing movements, including the communist French Section of the Communist International [SFIC – Section française de l’Internationale communiste, also known as the French Communist Party, (PCF – Parti communiste français )], the socialist French Section of the Workers’ International [SFIO – Section française de l’Internationale ouvrière], and the progressive Radical-Socialist Republican Party [PR – Parti radical, originally: PRRRS – Parti républicain, radical et radical-socialiste]. The “victorious” elections lead to the formation of a government first headed by SFIO leader Léon Blum and exclusively composed of republican and SFIO ministers.

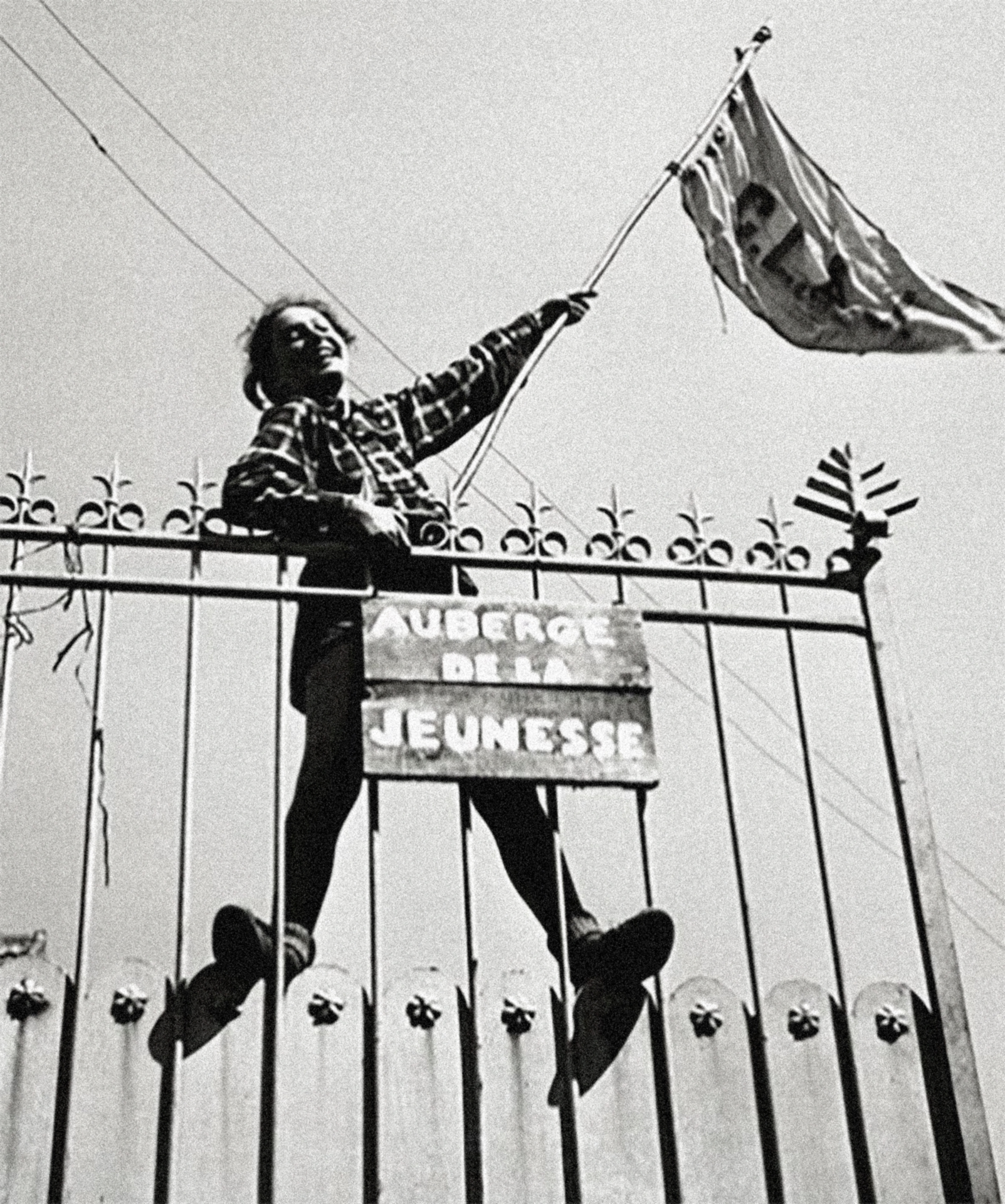

The Popular Front period unfolded against a backdrop of sharp political polarization and collective fear. The impact of the Great Depression, the ascendancy of international Fascism, particularly after Hitler’s seizure of power in 1933, and strategic shifts on the part of Stalin and the Communist International in favor of Popular Front alliances combined to produce a re-evaluation of the intellectual’s role in the struggle for political and social justice. Antifascist intellectuals provided the French coalition with moral authority, prestige, ideological legitimacy, a rhetoric of hope, and a cultural effervescence in the theaters, cinemas, universities, and artistic associations. Left-wing artists such as Romain Rolland participated in or supported experiments in popular education: worker universities, agitprop theater, social cinema, and the proliferation of Houses of Culture. The cultural goal of the Popular Front was to “open the gates of culture”. It coincided with the tendency of French cultural life from the early 1930s: artists and intellectuals—especially the younger generation—forsook academic careers in favor of the political engagement of writing mass-market journalism or direct “field work”. The Association des Écrivains et Artistes Révolutionnaires [AEAR – Association of Revolutionary Artists and Writers], with its extensive and prestigious membership was at the forefront of this movement. The move of French intellectuals out of the ivory tower and into the street was closely followed by Hungarian left-wing intellectuals—among them Attila József, who regularly discussed the latest writings by André Malraux and André Gide with his circle of friends.

French Communists in the Popular Front must be credited with “greatly and permanently enhancing the state’s administrative and financial responsibility for cultural life”, but their view of culture was extremely conservative: it was high French culture, as the surrealists found during their brief alliance with the PCF. Under the Popular Front, the remarriage of social revolution and patriotic sentiment was an extremely complex phenomenon. The right had to a certain extent forfeited its nationalist claims by expressing sympathy with Fascism: there was a French phrase: “better Hitler than Léon Blum”. The Stalin-Laval mutual aid pact, moreover, had directly contributed to the change of policy on the part of the PCF, and to the ex-surrealist Louis Aragon’s new-found, nationalist enthusiasm for “Réalisme socialiste, Réalisme français” [Socialist realism, French Realism].

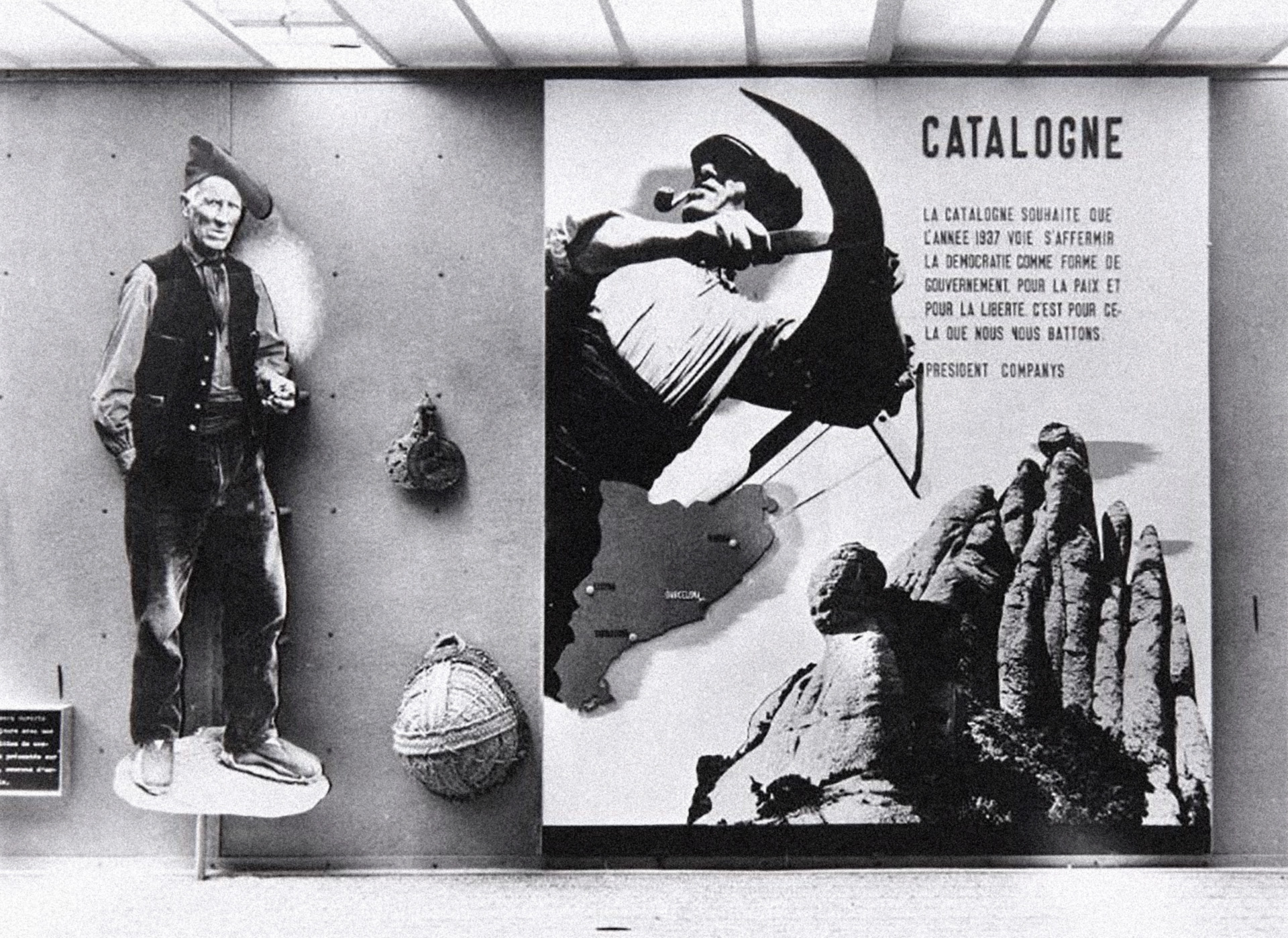

But it was not only French intellectuals and artists who formed the culture of the Popular Front period. Paris was not only the art capital of the world at this time, but also a safe haven for artists fleeing their respective countries (such as Germany, Italy, Hungary, etc.), who organized and participated in the cultural life of the Popular Front, as well as documenting its major events. One of the most important cultural events of the period was the International Exhibition of Art and Technology in Modern Life [Exposition international des Arts et des Techniques dans la Vie moderne], which was intended to be a people’s festival, a real celebration of international culture. Instead, it became a power demonstration for Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, as well as a cry for help by the Spanish Republic.

The utopian impetus of the Front Populaire was broken by the realities of the mid-1930s. The Front Populaire saw its adventurous plans for social reform increasingly frustrated by a policy of non-intervention in Spain, internal strikes, the devaluation of the franc and the necessity for rearmament. The coalition fell in June 1937; Blum was reelected again in March 1938, but was only Prime Minister for a couple of months—at least, long enough to ship heavy artillery and other much needed military equipment to the Spanish Republicans. April 1938 saw the reinstatement of the centrist Édouard Daladier as Prime Minister—and Europe on the brink of the Second World War. The Popular Front coalition itself collapsed definitively in November 1938, two months after the signing of the Munich Accords that made war between France and Germany inevitable.

The period between 1931 and 1936/1939 is known in Spain as the Segunda República Española [Second Spanish Republic]. When the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera fell in 1930, and in 1931 the monarchists lost the elections, the majority of the population welcomed the Republic with joy, and high hopes were attached to democracy. And so the Republic was immediately given a nickname: la niña bonita, [the beautiful girl]. However, as the governments changed again and again, and their attempts to renew Spain failed, these high hopes were lost, and the division between the opposing sides of Spanish society grew deeper than ever. One side of “The Two Spains” (a term coined by the poet Antonio Machado in 1917) was clerical, absolutist and reactionary, and the other secular, constitutional and progressive. Naturally, the populacho—the mass of the common people who were concerned with their everyday struggles—were not loyal to either of these sides on any long term basis. Attila József also dedicated the poem Egy spanyol földmíves sírverse [A Spanish peasant's epitaph, 1936] to the everyday Spaniards, who were torn between the two Spains.

The Spanish Frente Popular [Popular Front] defeated the National Front (a collection of right-wing parties) and won the 1936 elections, three months before the victory of the Front Populaire in France. The new government was welcomed with cheerful enthusiasm by one side, and bitter disappointment and rage by the other. It was only a matter of a few months before the two sides leapt at each other’s throats, and the former political split turned into a bitter armed conflict. From the very beginning of the Spanish Civil War, art was seen by Republicans and Nationalists alike as an essential part of the larger battle. While the Nationalist side condemned the Republicans for being barbaric, the Republicans organized the Second International Congress of Writers for the Defense of Culture, to prove to the world that it was “la república des intelectuales” [the Republic of Intellectuals]. And this was nowhere more clearly shown than at the International Exhibition in Paris in 1937, where the famous pavilion of the Spanish Republic vied with the rival contribution of Franco’s nationalists for the attention of visitors from all over the world.

How had this come about? On July 17, 1936 general Francisco Franco took charge of the troops in Spain’s North African colony and started an armed insurrection against the Popular Front government of the Spanish Republic. The rebels accused the democratically elected rulers of being tools of Moscow, intent on destroying Spain, and proclaimed their intention to reestablish order and protect the unity and integrity of the nation. Specifically, the republicans had introduced dramatic social changes to transform the essentially feudal social structures that the Nationalists wanted to see preserved. Notwithstanding an international non-intervention treaty, Germany and Italy openly supported Franco’s nationalists. The Soviet Union and international left-wing organizations came to the aid of the Republic, though in a far less substantial manner. Interestingly, both Right and Left drew attention to the foreign supporters of the other side and represented themselves as defending Spain against foreign aggression.

The Nationalists’ value system was based on tradition, and in particular on the link between State and Church. They presented themselves as the spiritual heirs of Ferdinand and Isabella, the Reyes Católicos [Catholic Kings], who first united Spain in the 15th century in the name of Christianity. Shadowing the Italian Fascist fascination with the Roman Empire and similar mythologizing by the Nazis, they drew on the symbolic insignia of the former Spanish empire for their own corporate identity. The very manifesto with which Franco launched the military uprising “in the Holy Name of Spain” aimed to justify armed intervention by accusing the Republican government of supporting attacks on “monuments and artistic treasures”. This set the tone for the most sustained strand of the Nationalists’ propaganda effort. The Republicans, on the other hand, saw art as part of a program of social-political change informed by the theories of the progressive and political left in Europe and Latin America; they eagerly espoused the revolutionary art and culture of the Weimar Republic, Mexico and the Soviet Union, on the clear understanding that aesthetic and political concerns were part of the same package. It was evident that culture had been instrumental in shaping the ideological battleground, on which later the Second World War and the Cold War were to be waged.

As Attila József’s friend, the Hungarian-born British writer and journalist Arthur Koestler [Artúr Kösztler] wrote: “Like the best of his generation, Attila József was a Communist. But he turned his back on the movement, the distortion of which had cost the lives or sanity of many of these best men and women. And like many of the best, he was never able to overcome his disappointment. He was never able to rid himself of the mixture of hate and love that characterized his feelings for the Party, as none of us were able to do when we tasted it. For the Party was the card on which we had staked everything and on which we had lost everything.” Koestler was one of the first internationally renowned critics of the Stalinist dictatorship; his novel of 1940 Darkness at Noon explored the world of the Stalinist purges. The novel, quite understandably, was officially published in Hungarian for the first time only around the fall of Communism. Koestler is very apt when he describes the relationship between Attila József and the Party: the poet, who was constantly striving for love, was deeply shocked that the idea of Communism had not turned out as he had expected.

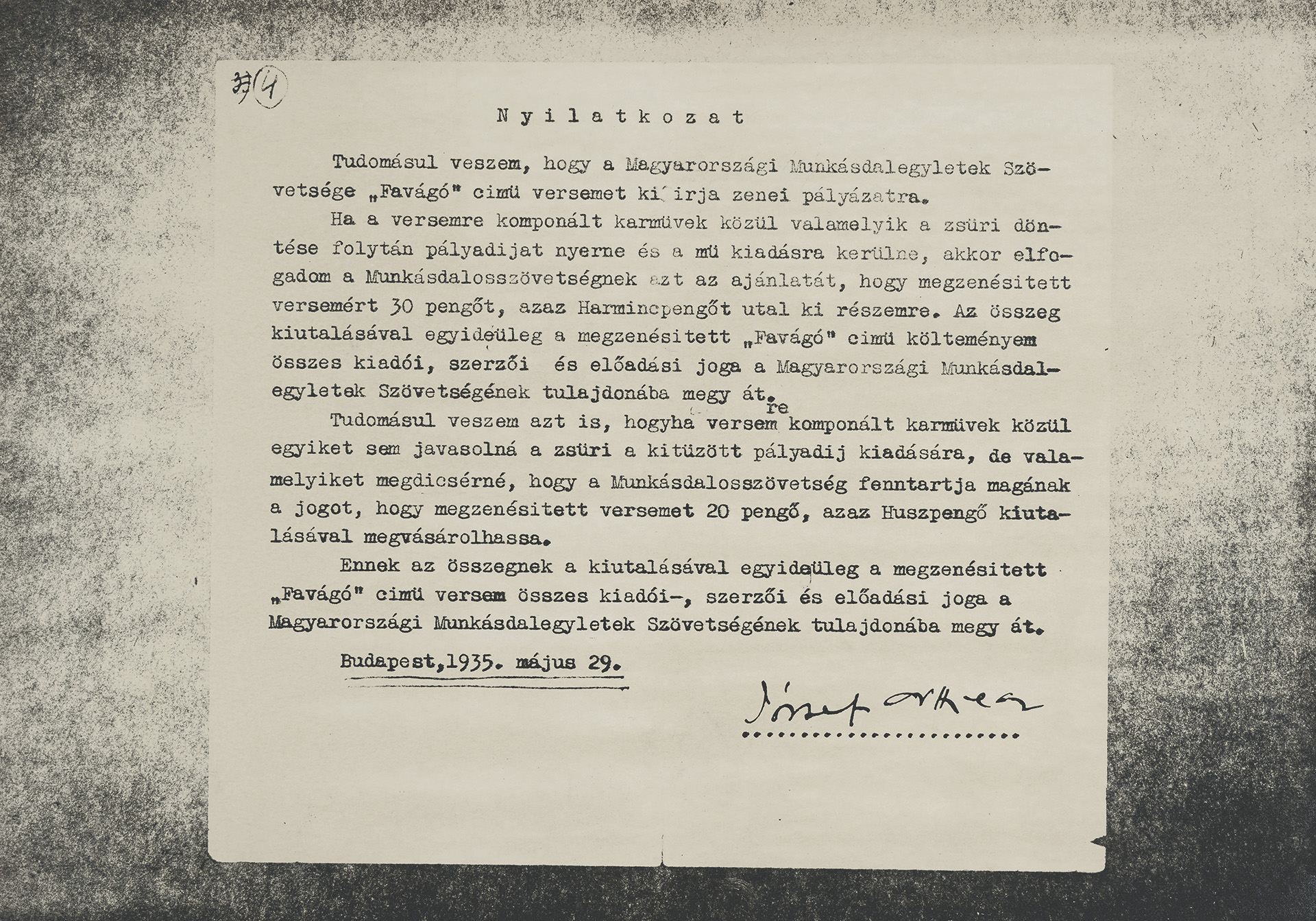

Attila József was inserted into the Communist pantheon, and he was appointed—retrospectively and erroneously—as its “official” poet, even though he was a member of the KMP (Communist Party of Hungary) for only a short time, and even these few years did not pass without friction. He already had links with left-wing (illegal or semi-illegal) organizations before he joined the KMP after the great workers’ demonstration of September 1930. (His poem Tömeg [Mass] was inspired by this event). A year later, in September 1931, he wrote to a friend: “I have been an active member of the illegal Communist Party for more than a year; as a party member I started out typing pamphlets and stencils, I have seven seminars and I give lectures to hundreds of people every Sunday.” Attila József worked first for trade unions and then for semi-legal cultural organizations. Later he also gave seminars and lectures to workers, and at one point he was involved in the illegal work of the Party. He went to the factories of Újpest and Csepel to agitate the workers, and on Sundays he took part in the famous Göd excursions (which were important events in workers’ culture at the time). His friend, the writer Andor Németh, recalled this period a few years after his death: “When I think back on him, he was running down the street with a swollen briefcase, frowning, worried. The briefcase was new. It contained pamphlets reproduced for distribution, pamphlets in German and Hungarian on imperialist capitalism and the theory of surplus value, a German book with a blue print: Marx’s works from his youth, café-chantant poems with a bouncing beat and a recurring refrain, recitation poems with an incendiary effect. [...]... at this time he devoted all his talents and time to the Party, [...] doing Party work, giving seminars and writing poems that could only be distributed in secret.”

Indeed—and not for the first time—, he had several run-ins with the authorities: his book of poems of 1931, Döntsd a tőkét! [“Chop the Roots!” or “Knock Down the Capital!”], was confiscated by the authorities, and he also had to stand trial for another of his poems, Lebukott [Busted]. His steadfastness and enthusiasm, however, were seen by many of his fellow party members as over-excited unreliability; on the other hand, the “narrow conceptual culture” promoted by the Soviet party guidelines and some Hungarian writers was unacceptable to the poet. Although he was writing poems to agitate at this time—including poems for workers’ choirs—he often clashed with the party leadership. The final break came in 1933, with the publication of his essay Az egységfront körül [On the United Front], in which he called for the unity of left-wing parties and organizations at a time when the official Communist position had not yet moved towards the idea of the Popular Front. He still had left-wing affiliations after his break with the Party, but this confrontation left deep scars, and he became increasingly blunt in his condemnation of Communism. He came to see—as many other enthusiastic left-wing intellectuals were to see a generation later – that for all their noble ideals, the Communists’ methods were hardly distinguishable from those of the Fascists they were so valiantly combating. He expressed his disappointment most accurately in his poem Világosítsd föl [Enlighten your Child]: “the world needs order, and order exists … to ban what is good”. This ironic “new tale of fascist-communism” became the reality of the Stalinist era. The most striking proof of this is that this poem was omitted from his collected volumes at the very time when he was heralded as the official poet of the regime he ultimately condemned.

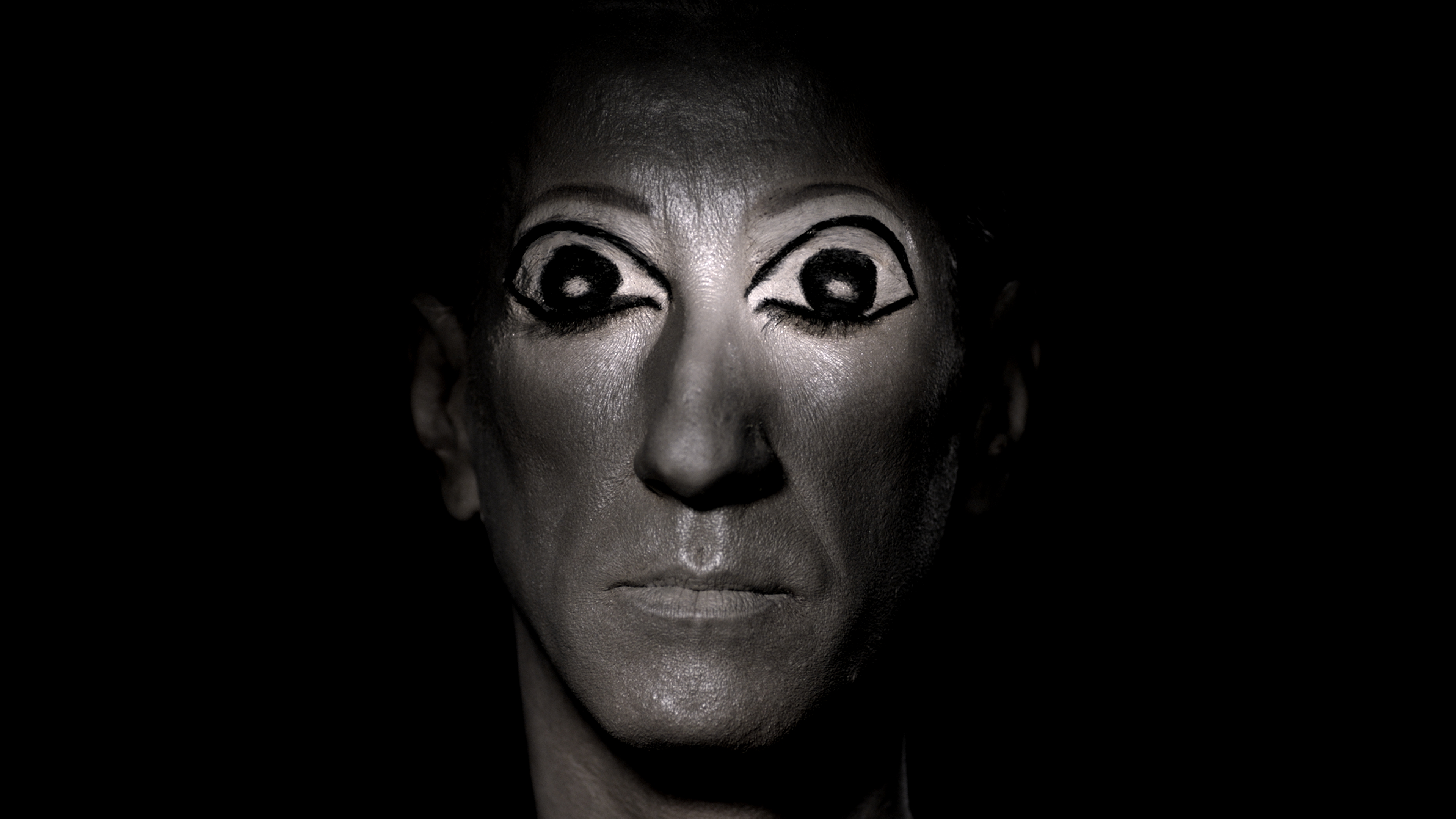

Damir Očko’s video collage, DICTA I. (2017) is the first part of an ongoing series of videos, looking at the impoverishment of language in the public space. “Dicta” comes from the Latin (the plural of ‘dictum’) and it refers to a formal pronouncement from an authoritative source or a short statement that expresses a general truth or principle. The film features the radical reading of a poem composed by the artist based on fragmented cut-outs from Bertolt Brecht’s literary-political essay, Fünf Schwierigkeiten beim Schreiben der Wahrheit [Writing the Truth: Five Difficulties]. Written in 1934, after Hitler’s rise to power, the German exiled playwright directed this text principally at those writers who had remained in Germany, demanding that “a writer should write the truth in the sense that he should not suppress it or keep it to himself and that he should not write anything untrue. He should not bow down to the powerful, he should not betray the weak”. In the film Očko not only revisits and re-reads the text, but by cutting and rearranging the words in a Dadaist manner he composes a randomized, radical, sometimes incomprehensible speech that by means of its own rearranged and manipulated structure proposes a critical commentary on the construction of meaning in the age of “alternative facts”. As he himself put it: “The poem from Dicta I is a Dada cut-out text by Brecht, full of mistakes, strange constellations, and nonsense. I created the subtitles using Google translate, which gave the work a dimension that was conceptually fitting and clear.” The spoken sentences, uttered by a man in theatre greasepaint, are reminiscent of political slogans, their content becoming increasingly meaningless through constant repetition and because of the fact that their presentation always strives for a dramatic effect. In times of alternative facts, Damir Očko’s films seem more relevant than ever: reminiscent of Bertolt Brecht’s call for truth and exposing the lack of content of political slogans. As Očko himself put it, Dicta I. “refers to the idea of fabricating a sense of truth out of completely false information. I find it particularly relevant for how the political discourse currently works, like a manipulative form of mimicry. Dicta I explores this mimicry by re-collaging a very important text by Bertolt Brecht, Writing the Truth: Five Difficulties, into something that sounds right and truthful but is, in reality, complete nonsense.”