As Attila József’s friend, the Hungarian-born British writer and journalist Arthur Koestler [Artúr Kösztler] wrote: “Like the best of his generation, Attila József was a Communist. But he turned his back on the movement, the distortion of which had cost the lives or sanity of many of these best men and women. And like many of the best, he was never able to overcome his disappointment. He was never able to rid himself of the mixture of hate and love that characterized his feelings for the Party, as none of us were able to do when we tasted it. For the Party was the card on which we had staked everything and on which we had lost everything.” Koestler was one of the first internationally renowned critics of the Stalinist dictatorship; his novel of 1940 Darkness at Noon explored the world of the Stalinist purges. The novel, quite understandably, was officially published in Hungarian for the first time only around the fall of Communism. Koestler is very apt when he describes the relationship between Attila József and the Party: the poet, who was constantly striving for love, was deeply shocked that the idea of Communism had not turned out as he had expected.

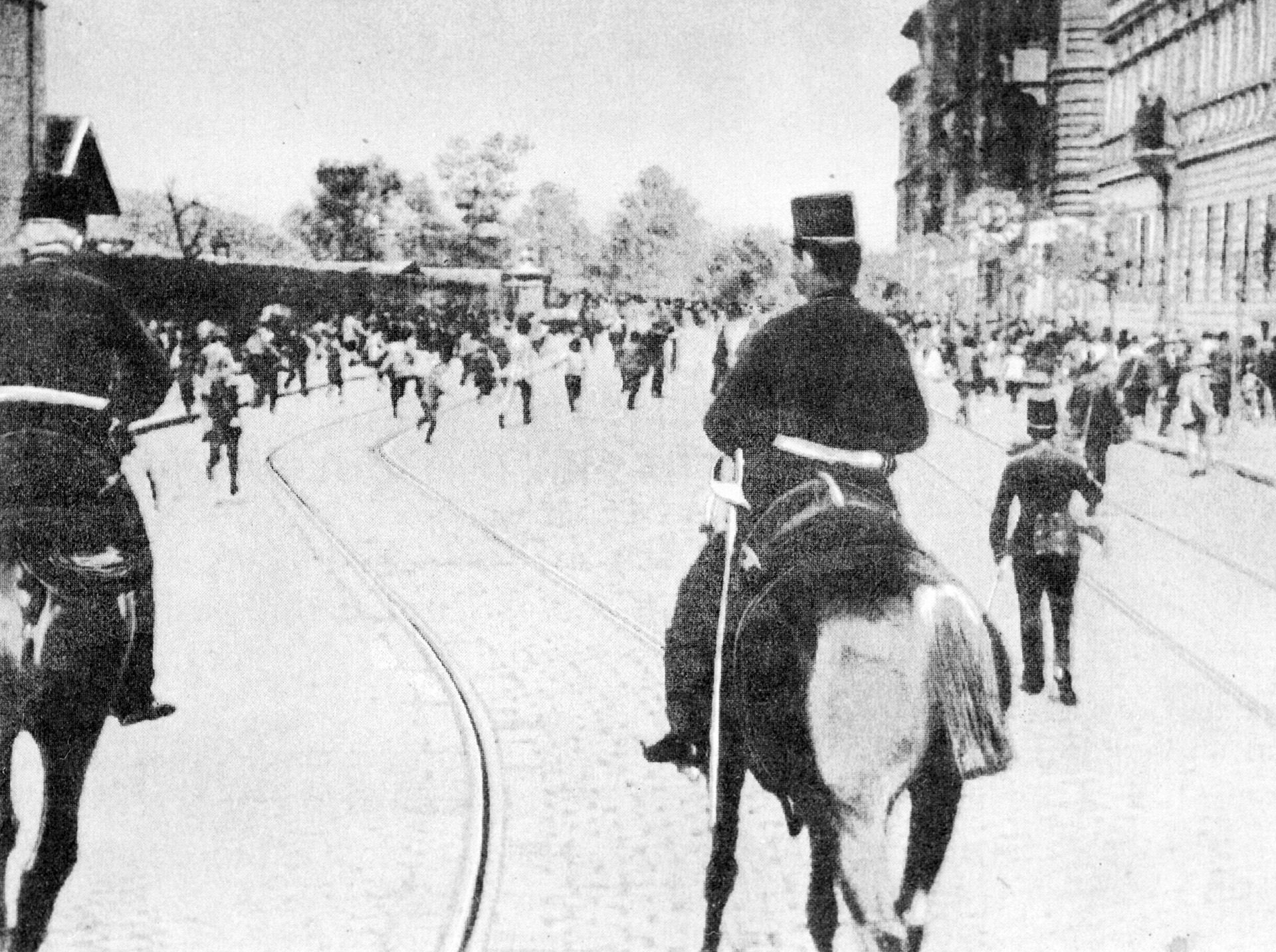

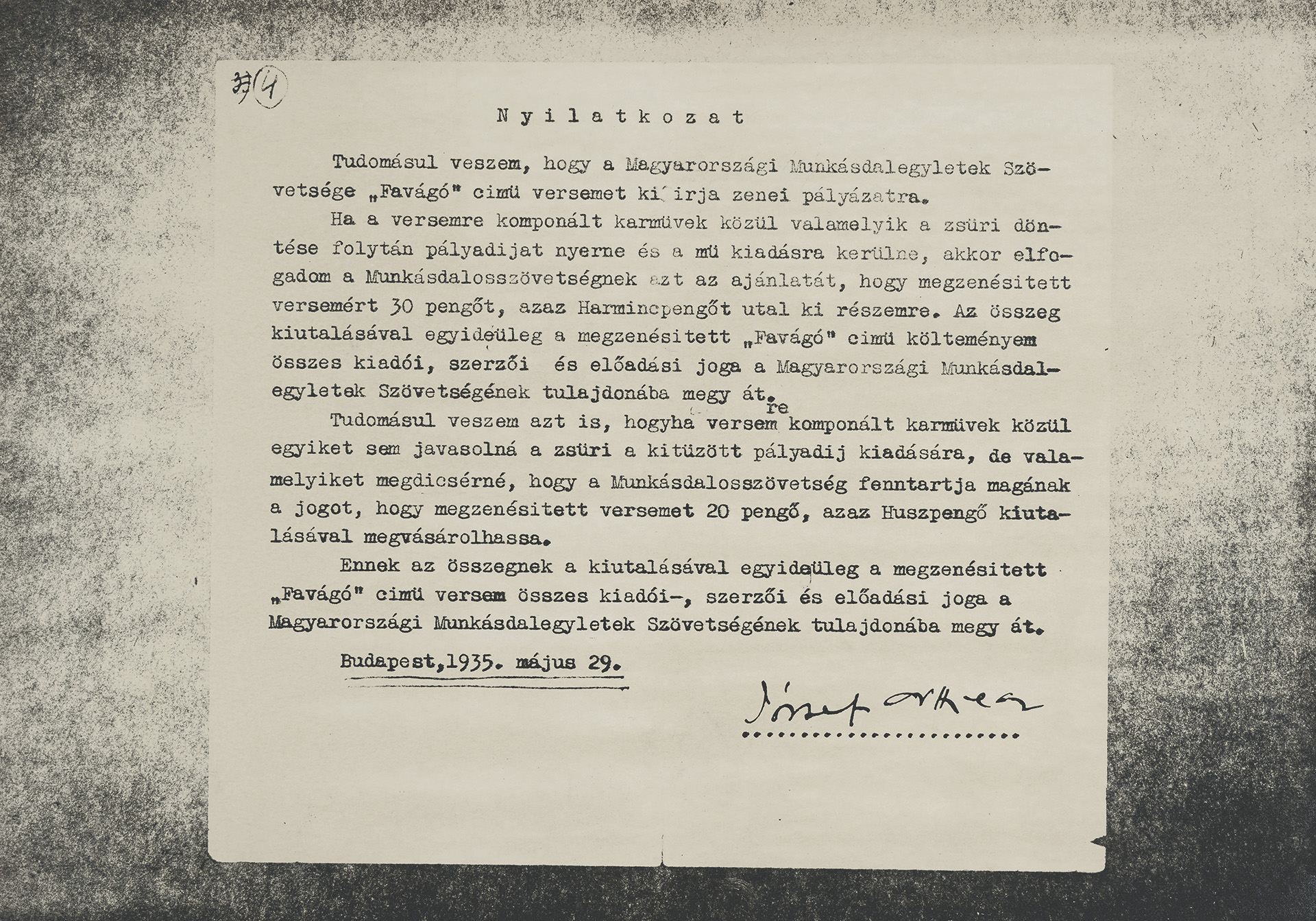

Attila József was inserted into the Communist pantheon, and he was appointed—retrospectively and erroneously—as its “official” poet, even though he was a member of the KMP (Communist Party of Hungary) for only a short time, and even these few years did not pass without friction. He already had links with left-wing (illegal or semi-illegal) organizations before he joined the KMP after the great workers’ demonstration of September 1930. (His poem Tömeg [Mass] was inspired by this event). A year later, in September 1931, he wrote to a friend: “I have been an active member of the illegal Communist Party for more than a year; as a party member I started out typing pamphlets and stencils, I have seven seminars and I give lectures to hundreds of people every Sunday.” Attila József worked first for trade unions and then for semi-legal cultural organizations. Later he also gave seminars and lectures to workers, and at one point he was involved in the illegal work of the Party. He went to the factories of Újpest and Csepel to agitate the workers, and on Sundays he took part in the famous Göd excursions (which were important events in workers’ culture at the time). His friend, the writer Andor Németh, recalled this period a few years after his death: “When I think back on him, he was running down the street with a swollen briefcase, frowning, worried. The briefcase was new. It contained pamphlets reproduced for distribution, pamphlets in German and Hungarian on imperialist capitalism and the theory of surplus value, a German book with a blue print: Marx’s works from his youth, café-chantant poems with a bouncing beat and a recurring refrain, recitation poems with an incendiary effect. [...]... at this time he devoted all his talents and time to the Party, [...] doing Party work, giving seminars and writing poems that could only be distributed in secret.”

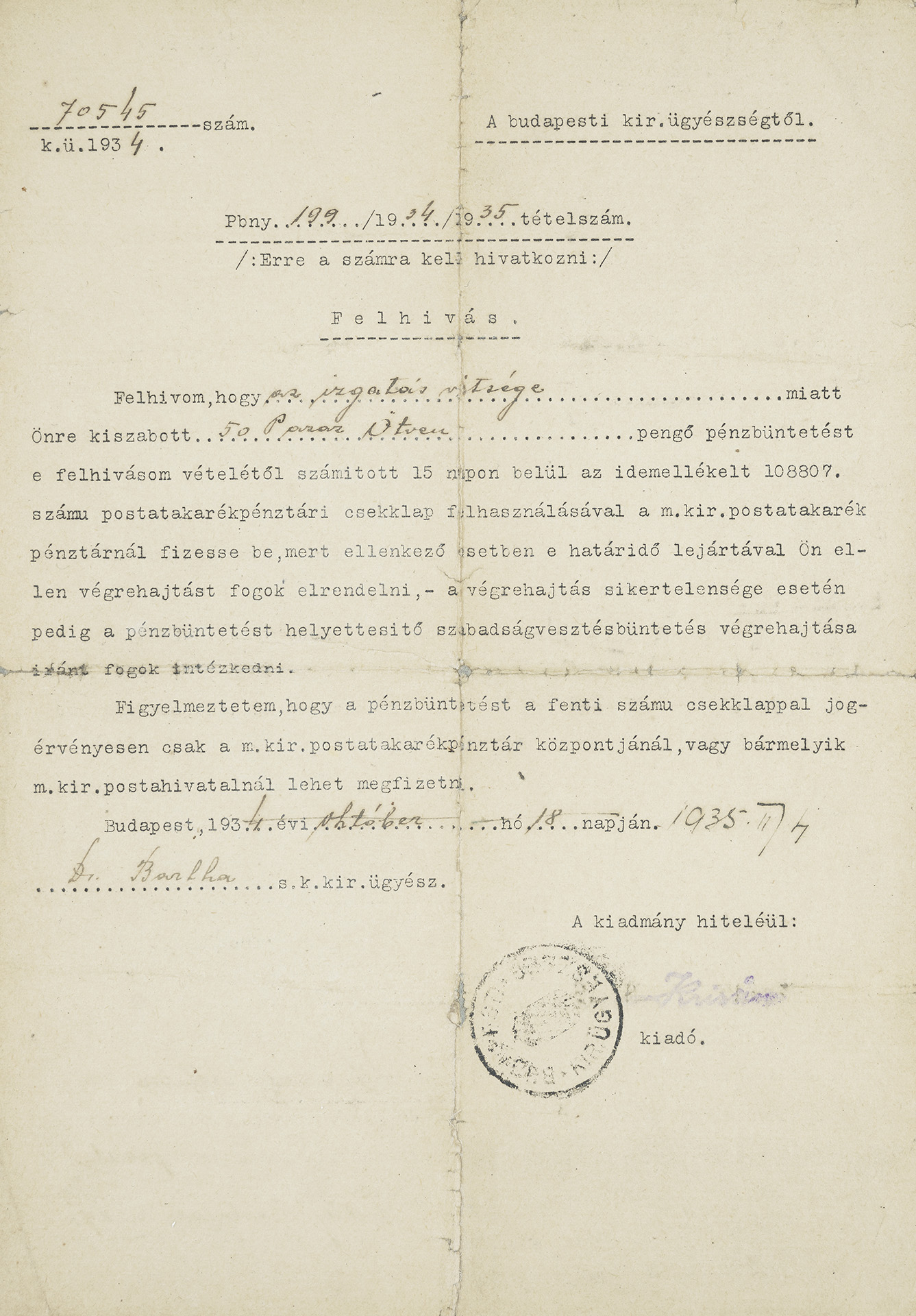

Indeed—and not for the first time—, he had several run-ins with the authorities: his book of poems of 1931, Döntsd a tőkét! [“Chop the Roots!” or “Knock Down the Capital!”], was confiscated by the authorities, and he also had to stand trial for another of his poems, Lebukott [Busted]. His steadfastness and enthusiasm, however, were seen by many of his fellow party members as over-excited unreliability; on the other hand, the “narrow conceptual culture” promoted by the Soviet party guidelines and some Hungarian writers was unacceptable to the poet. Although he was writing poems to agitate at this time—including poems for workers’ choirs—he often clashed with the party leadership. The final break came in 1933, with the publication of his essay Az egységfront körül [On the United Front], in which he called for the unity of left-wing parties and organizations at a time when the official Communist position had not yet moved towards the idea of the Popular Front. He still had left-wing affiliations after his break with the Party, but this confrontation left deep scars, and he became increasingly blunt in his condemnation of Communism. He came to see—as many other enthusiastic left-wing intellectuals were to see a generation later – that for all their noble ideals, the Communists’ methods were hardly distinguishable from those of the Fascists they were so valiantly combating. He expressed his disappointment most accurately in his poem Világosítsd föl [Enlighten your Child]: “the world needs order, and order exists … to ban what is good”. This ironic “new tale of fascist-communism” became the reality of the Stalinist era. The most striking proof of this is that this poem was omitted from his collected volumes at the very time when he was heralded as the official poet of the regime he ultimately condemned.

Visitors to the Attila József exhibition at the National Salon, June, 1955

bw. photo, exhibition print

Hungarian National Museum – Historical Photo Department, Budapest, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Mounted police disperse a workers’ demonstration in Budapest, September 1, 1930

bw. photo, exhibition print

MTVA – National Photo Archive, Budapest

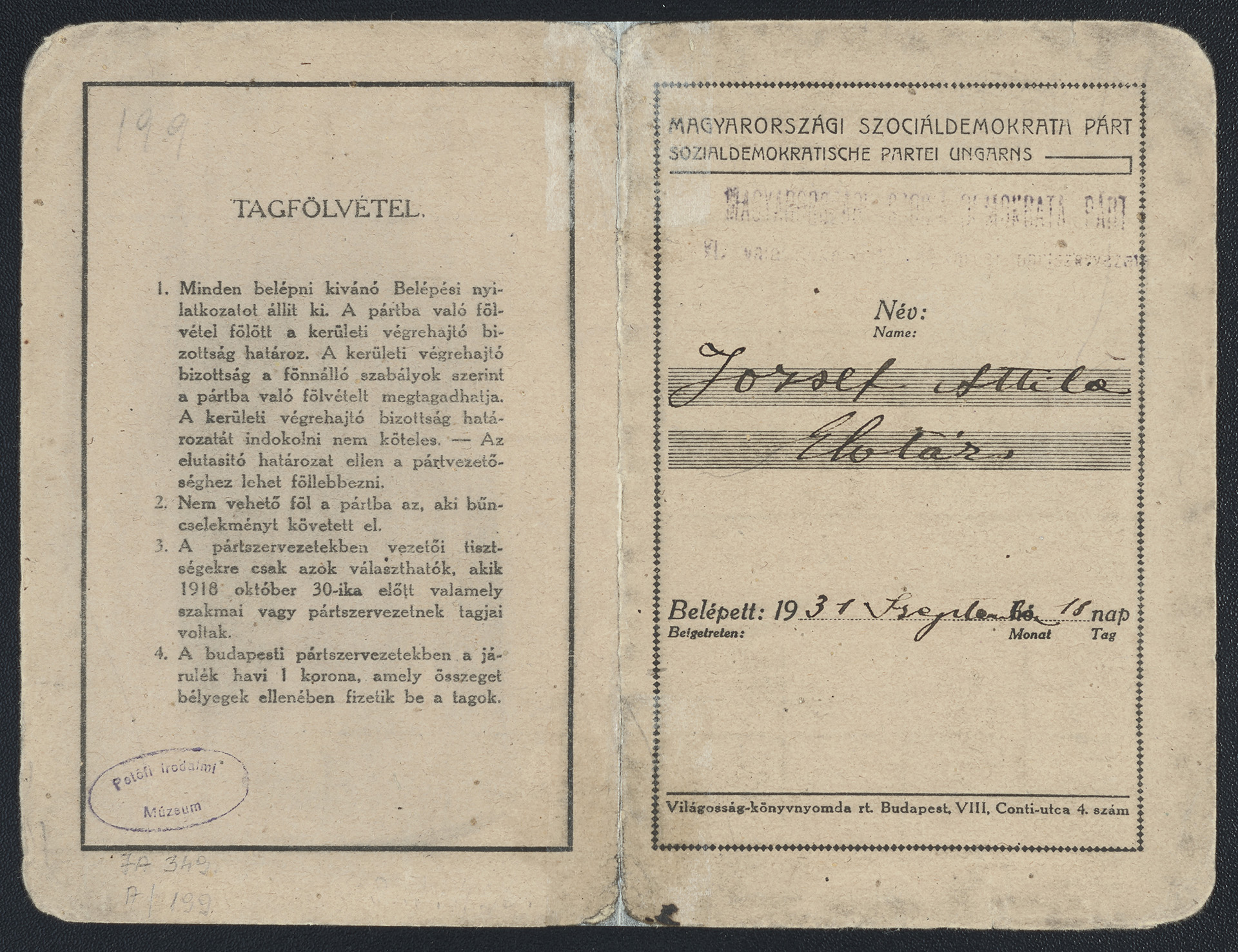

Membership card of the Magyarországi Szociáldemokrata Párt, [MSZDP, Hungarian Social Democratic Party] for Attila József, 18 September 1931

personal document, exhibition print

Petőfi Literary Museum – Manuscript Collection, Budapest

Documents of the press trial for Attila József’s poem Lebukott [Busted], 1934–35

typescript, signed, exhibition print

Petőfi Literary Museum – Manuscript Collection, Budapest

Statement by Attila József to the Magyarországi Munkásdalegyletek Szövetsége [Association of Hungarian Workers’ Choirs], May 29, 1935.

typescript, signed, exhibition print

Petőfi Literary Museum – Manuscript Collection, Budapest