The period between 1931 and 1936/1939 is known in Spain as the Segunda República Española [Second Spanish Republic]. When the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera fell in 1930, and in 1931 the monarchists lost the elections, the majority of the population welcomed the Republic with joy, and high hopes were attached to democracy. And so the Republic was immediately given a nickname: la niña bonita, [the beautiful girl]. However, as the governments changed again and again, and their attempts to renew Spain failed, these high hopes were lost, and the division between the opposing sides of Spanish society grew deeper than ever. One side of “The Two Spains” (a term coined by the poet Antonio Machado in 1917) was clerical, absolutist and reactionary, and the other secular, constitutional and progressive. Naturally, the populacho—the mass of the common people who were concerned with their everyday struggles—were not loyal to either of these sides on any long term basis. Attila József also dedicated the poem Egy spanyol földmíves sírverse [A Spanish peasant's epitaph, 1936] to the everyday Spaniards, who were torn between the two Spains.

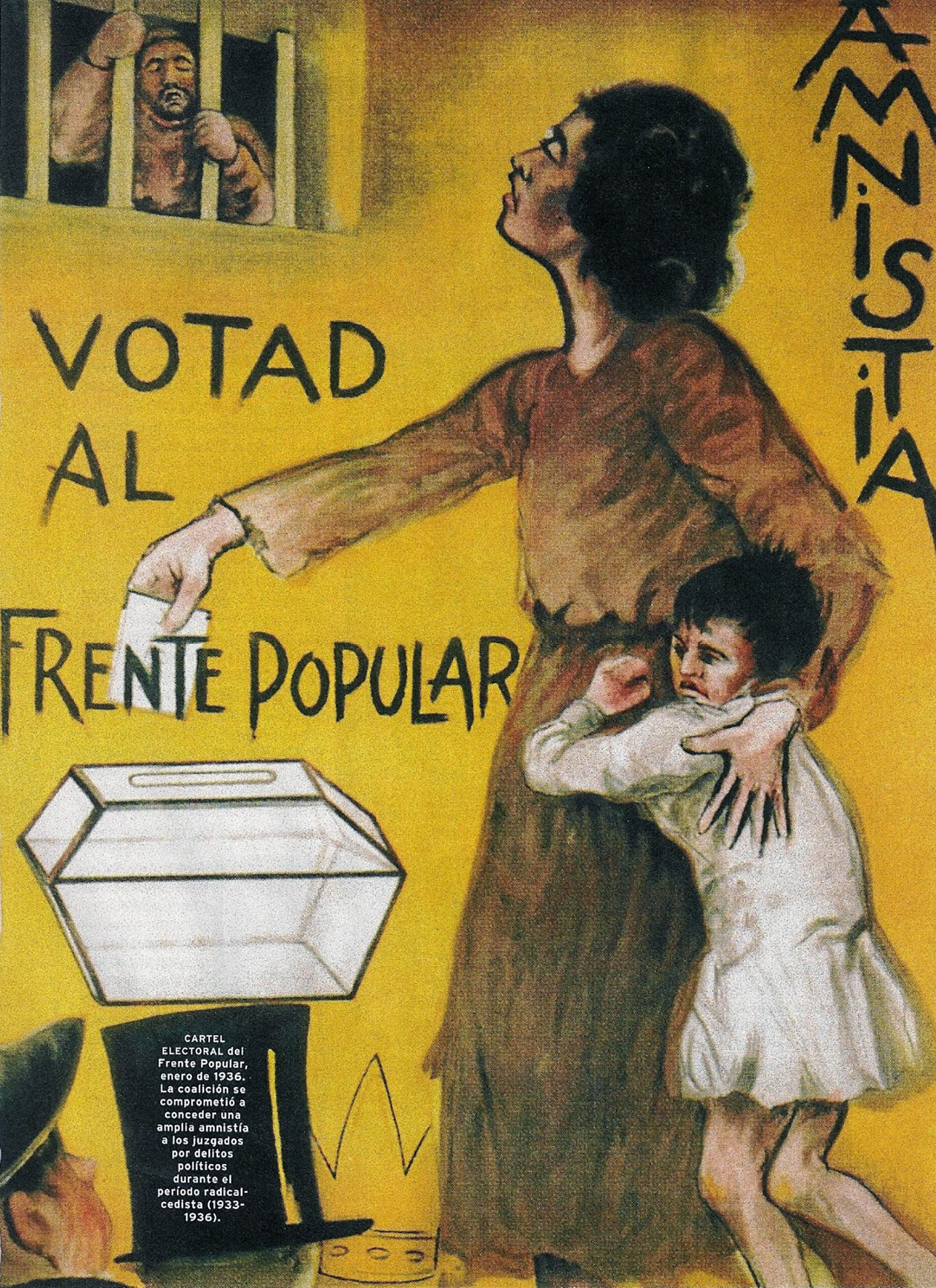

The Spanish Frente Popular [Popular Front] defeated the National Front (a collection of right-wing parties) and won the 1936 elections, three months before the victory of the Front Populaire in France. The new government was welcomed with cheerful enthusiasm by one side, and bitter disappointment and rage by the other. It was only a matter of a few months before the two sides leapt at each other’s throats, and the former political split turned into a bitter armed conflict. From the very beginning of the Spanish Civil War, art was seen by Republicans and Nationalists alike as an essential part of the larger battle. While the Nationalist side condemned the Republicans for being barbaric, the Republicans organized the Second International Congress of Writers for the Defense of Culture, to prove to the world that it was “la república des intelectuales” [the Republic of Intellectuals]. And this was nowhere more clearly shown than at the International Exhibition in Paris in 1937, where the famous pavilion of the Spanish Republic vied with the rival contribution of Franco’s nationalists for the attention of visitors from all over the world.

How had this come about? On July 17, 1936 general Francisco Franco took charge of the troops in Spain’s North African colony and started an armed insurrection against the Popular Front government of the Spanish Republic. The rebels accused the democratically elected rulers of being tools of Moscow, intent on destroying Spain, and proclaimed their intention to reestablish order and protect the unity and integrity of the nation. Specifically, the republicans had introduced dramatic social changes to transform the essentially feudal social structures that the Nationalists wanted to see preserved. Notwithstanding an international non-intervention treaty, Germany and Italy openly supported Franco’s nationalists. The Soviet Union and international left-wing organizations came to the aid of the Republic, though in a far less substantial manner. Interestingly, both Right and Left drew attention to the foreign supporters of the other side and represented themselves as defending Spain against foreign aggression.

The Nationalists’ value system was based on tradition, and in particular on the link between State and Church. They presented themselves as the spiritual heirs of Ferdinand and Isabella, the Reyes Católicos [Catholic Kings], who first united Spain in the 15th century in the name of Christianity. Shadowing the Italian Fascist fascination with the Roman Empire and similar mythologizing by the Nazis, they drew on the symbolic insignia of the former Spanish empire for their own corporate identity. The very manifesto with which Franco launched the military uprising “in the Holy Name of Spain” aimed to justify armed intervention by accusing the Republican government of supporting attacks on “monuments and artistic treasures”. This set the tone for the most sustained strand of the Nationalists’ propaganda effort. The Republicans, on the other hand, saw art as part of a program of social-political change informed by the theories of the progressive and political left in Europe and Latin America; they eagerly espoused the revolutionary art and culture of the Weimar Republic, Mexico and the Soviet Union, on the clear understanding that aesthetic and political concerns were part of the same package. It was evident that culture had been instrumental in shaping the ideological battleground, on which later the Second World War and the Cold War were to be waged.

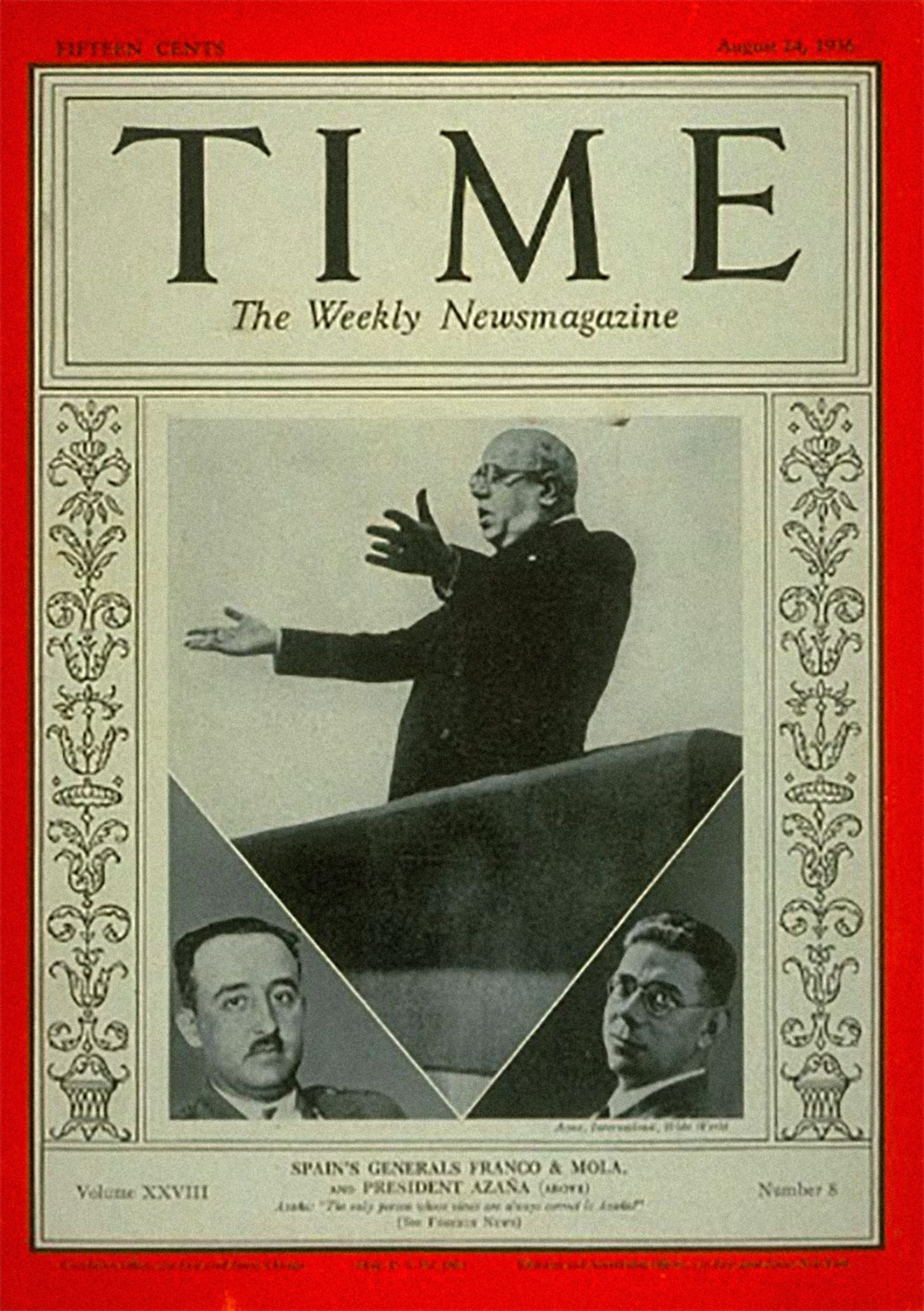

Cover of Time Magazine: (from left to right) Spanish General Francisco Franco, President Manuel Azaña and General Emilio Mola, August 24, 1936

exhibition print

© ACME; INTERNATIONAL; WIDE WORLD / Time Inc.

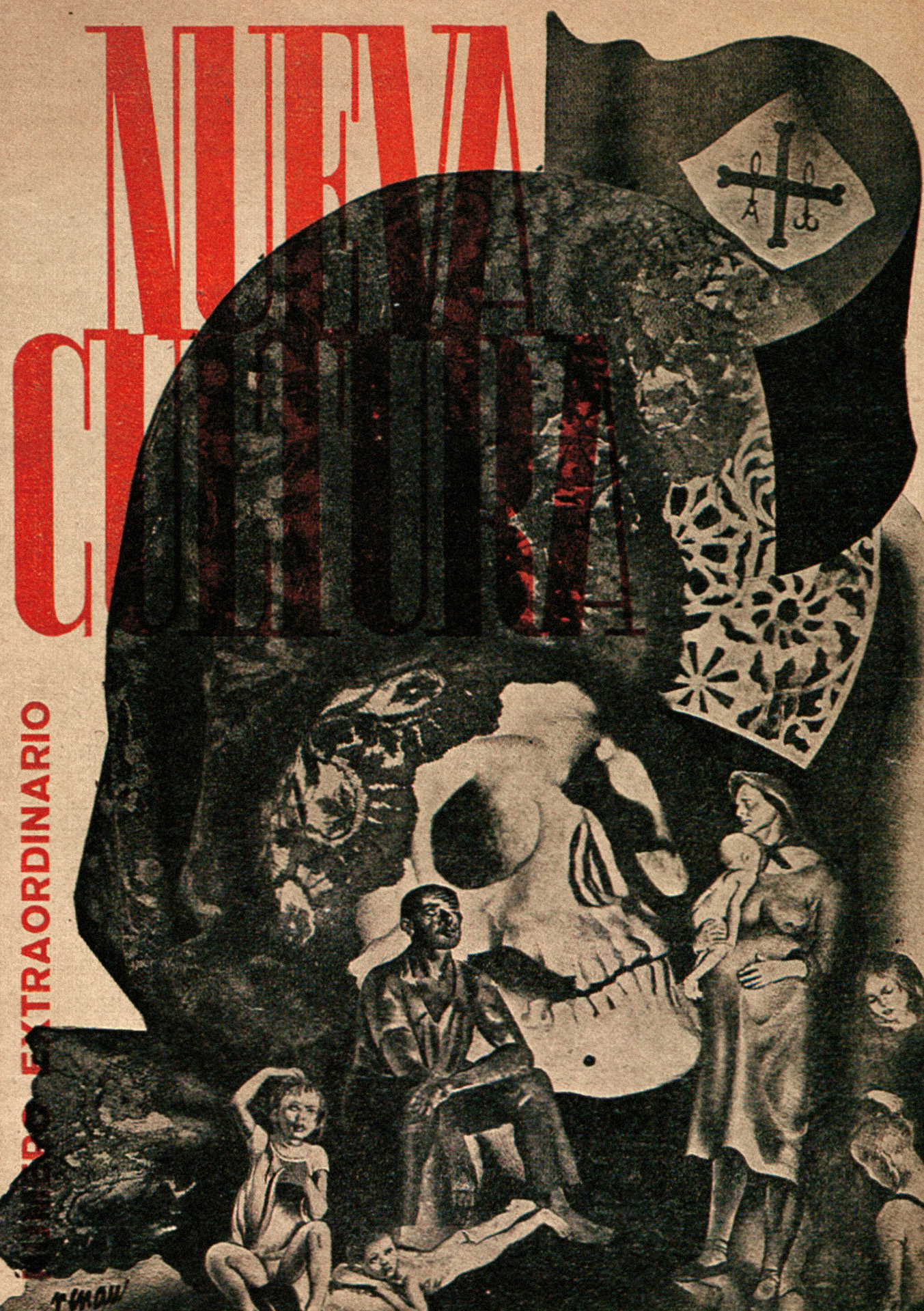

Josep Renau, Cover of a special issue of Nueva Cultura [New Culture], 1935

magazin cover, exhibition print

IVAM – Instituto Valenciano de Arte Moderna, Valencia

Report in the illustrated supplement of Pesti Napló on the Spanish Civil War, 1936

exhibition print

Pesti Napló Képes Melléklete [Illustrated Supplement of Pesti Napló], November 22, 1936 / Arcanum

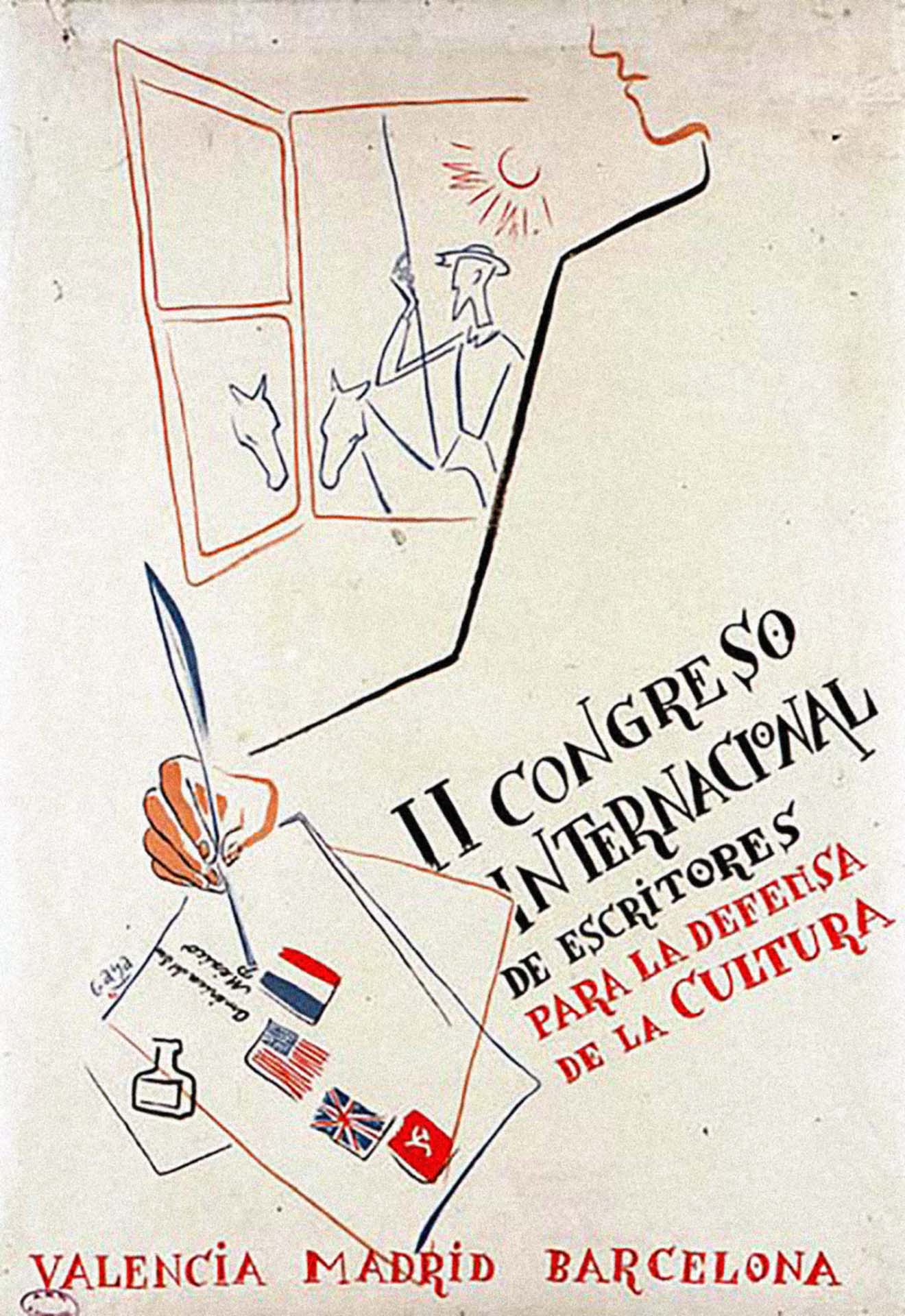

Poster of the Second International Congress of Writers for the Defense of Culture, 1937

poster (design by Ramón Gaya), exhibition print

wikimedia commons

The Frente Popular [Popular Front, or Front d'Esquerres, Left Front] was initiated by the writer and left-wing radical politician Manuel Azaña for the purpose of contesting the 1936 election. The Popular Front included the Partido Socialista Obrero Español [PSOE, Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party], the Partido Comunista de España [PCE, Communist Party of Spain], the Trotskyist Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista [POUM, Workers’ Party of Marxist Unification] and the republicans: Azaña’s party, the left-wing Izquierda Republicana [IR, Republican Left] and the Unión Republicana [UR, Republican Union], led by Diego Martínez Barrio. This pact was supported by the Galician nationalist Partido Galeguista [PG, Galician Party] and the Catalan nationalist Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya [ERC, Republican Left of Catalonia] and other minor parties, as well as the socialist trade union, the Unión General de Trabajadores [UGT, Workers’ General Union], and the anarchist trade union, the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo [CNT, National Confederation of Labor]. Many anarchists who would later fight alongside Popular Front forces during the Spanish Civil War did not support them in the election, urging abstention instead. The strategy of the Popular Front was successful: the coalition secured 34.3% of the votes and a majority of seats in the Cortes. To the dismay of many moderates and political conservatives, the new government began taking bold political steps, such as freeing of leftist political prisoners from jail without any due process of law, giving back to Catalonia much of its previous political and administrative autonomy, and taking the initiative in agricultural reforms. As part of their political strategy, the Frente Popular sought to dominate the Spanish government and to expel out all political conservatives. This agenda was made dramatically clear when Manuel Azaña, a prominent member of the Frente Popular, took the presidency away from the moderately conservative Niceto Alcalá-Zamora. In this political assault on conservatives, many Spanish Army officers began considering plans to restore a more conservative Spanish government. Within months, the plan became a reality as General Franco and several other disaffected Spanish officers initiated the coup d’etat that eventually became the Spanish Civil War on July 17, 1936. The Popular Front government retreated to Valencia, and beside the war, it was torn by conflicts between the ideologies of many of the parties. The only factor that held them together was the common struggle against Fascism. After the Republican defeat in the Spanish Civil War, the Frente Popular was dissolved and the dictatorship of Francisco Franco began, lasting until his death in 1975.

“Votad al Frente Popular. AMNISTIA” [Vote for the Popular Front. AMNESTY], election poster, 1936

poster, exhibition print

University of California San Diego, Southwork Collection

The birth of the Frente Popular was not only a direct consequence of the Comintern’s new policy: Spain’s left-wing parties had already come to the conclusion that a unified front was necessary after the failure of the so-called Asturian Revolution in 1934. For two and a half years, from April 1931 to October 1933, the Second Spanish Republic was governed by a Republican-Socialist coalition. Successive cabinets, under the leadership of Manuel Azafia, initiated the separation of church and state, a massive program of school building, the granting of regional autonomy to the province of Catalonia, and the restructuring of the inefficient and politically dangerous army. In 1933, a right-wing coalition won, and struck down the radical labor movement. Franco’s colonial troops suppressed the rebellious coal miners in Asturias (winning the recognition of the Nationalist parties). When the Frente Popular won the election, several military leaders were “exiled” into colonial garrisons, including the notoriously anti-communist Franco.

Column of Guardias Civiles [civil guards] during the Asturian Revolution, Brañosera, 1934

bw. photo, exhibition print

Narodowe Archiwum Cyfrowe, Warsaw

During the election campaign of 1936, the program of the Frente Popular included a plan to free political prisoners. One of the beneficiaries of this policy was Lluis Companys, the President of the Generalitat of Catalunya [the Catalan Government], who had been jailed—along with the members of the Catalan Cabinet—after the Catalan Nationalist Uprising, and the proclamation of the Catalan state [Estat Català], which was envisioned as part of the Federal Republic of Spain. The question of the autonomy of Catalonia also became one of the program points of the Frente Popular. After the elections, Companys once again was in charge of the Catalan Government, which remained loyal to the Republic during the civil war. Exiled to France after the war, he was captured and handed over by the Gestapo to Madrid. He was executed by a firing squad on October 15, 1940 at the Montjuïc Castle. During his execution, he refused to wear the blindfold. When the execution squad executed the order, Companys allegedly shouted, “Per Catalunya!” [For Catalonia!].

The Catalan President Lluís Companys and the Catalan government in prison after declaring the independence of Catalonia, 1932

bw. photo, exhibition print

World History archive / Alamy

Lluís Companys, President of the Catalan Government, 1936

bw. photo, exhibition print

Arxiu Fotogràfic de Barcelona

One of the most burning issues the Frente Popular inherited from the previous governments of the Second Republic was the unsolved problem of the land reform. On the eve of the Second Republic, enormous estates were believed to be under-cultivated by their absentee owners, denying landless workers employment, and leading to widespread rural poverty in southern Spain. The slow implementation of a land reform deeply divided Spanish society, and is often cited as a cause of the outbreak of the civil war. In Extremadura, during the 1936 election campaign, Popular Front candidates had promised rapid land reform. Rather than wait for the government to deliver on its pledges, on 25 March 1936, 60,000 landless peasants in Badajoz led by the socialist land union, the Federación Nacional de Trabajadores de la Tierra or FNTT, took over 3,000 farms and started to plow. The government, faced with popular unrest, legalized the early occupations. By June 1936, 190,000 landless peasants had been settled in southern Spain. During the spring and summer, several meetings were held where the new farmers discussed whether the occupied farms should be collectivized or allotted to individual owners. The seizures—which were condemned by the former land-owners—thus provided not just land and work for the poor, but also a democratic forum, a focus for arguments about the future development of the society. But before the harvest was in, the Nationalist forces of General Franco occupied the territory and slaughtered many peasants and their leftist leaders during the Estremadura campaign.

David Seymour “Chim” [Dawid Szymin], Crowd at a land reform meeting, Estremadura, Badajoz, April–May 1936

bw. photo, exhibition print

© David Seymour / Magnum Photos

While Hitler and Mussolini shipped weapons and ammunition to the insurgents soon after the outbreak of the war, both France and Great Britain, fearing a general European war, adopted a policy of non-intervention in Spanish affairs. In this way, they effectively deprived a fellow democracy of the military assistance it urgently needed to put down the uprising. Partly to compensate for this policy, in the fall of 1936 the Soviet Union began to send military advisers and experts (and later weapons) to help the republicans, and also began to organize the International Brigades [Brigadas Internacionales]. However, in return for this not very substantial support, Stalin asked for the gold reserves of the Spanish Republic. (In addition to the Soviet Union, Mexico also provided assistance to the Spanish government). The International Brigades consisted of about 35,000 volunteers, not all of them Communists, from 50 countries who journeyed to enlist in the fight against Spanish Army troops, at that time rapidly advancing to Madrid. The first volunteers were the worker athletes who traveled to Barcelona to take part in the Olimpíada Popular—a Workers’ Olympics intended to counterbalance the Summer Olympics in Berlin—, which was canceled because of the outbreak of the civil war. Subsequently, the first major foreign contingent arrived in Spain in November and December 1936. They were mainly involved in the fighting around Madrid. A total of 1,200 Hungarians took part in the civil war until the spring of 1939, 600 of whom perished. Another 350-400 of them lost their lives in World War II fighting on the side of the Allies, or in German concentration or forced labor camps. In 1945, there were about 250 “spanyolos” [“from Spain]”, former fighters of the International Brigades, in Hungary. For many of them the real tribulations began only after the war: they were considered as “foreign agents” during the Stalinist Rákosi regime, and, as such, many of them fell victim to the purges related to the show trial of Foreign Secretary (former Minister of Interior) László Rajk, who was also a “spanyolos”.

David Seymour “Chim” [Dawid Szymin], A Spanish Civil War unit, composed of anti-Nazi Germans who fought for the Republic of Spain against Franco, Spain, 1936

bw. photo, exhibition print

© David Seymour / Magnum Photos

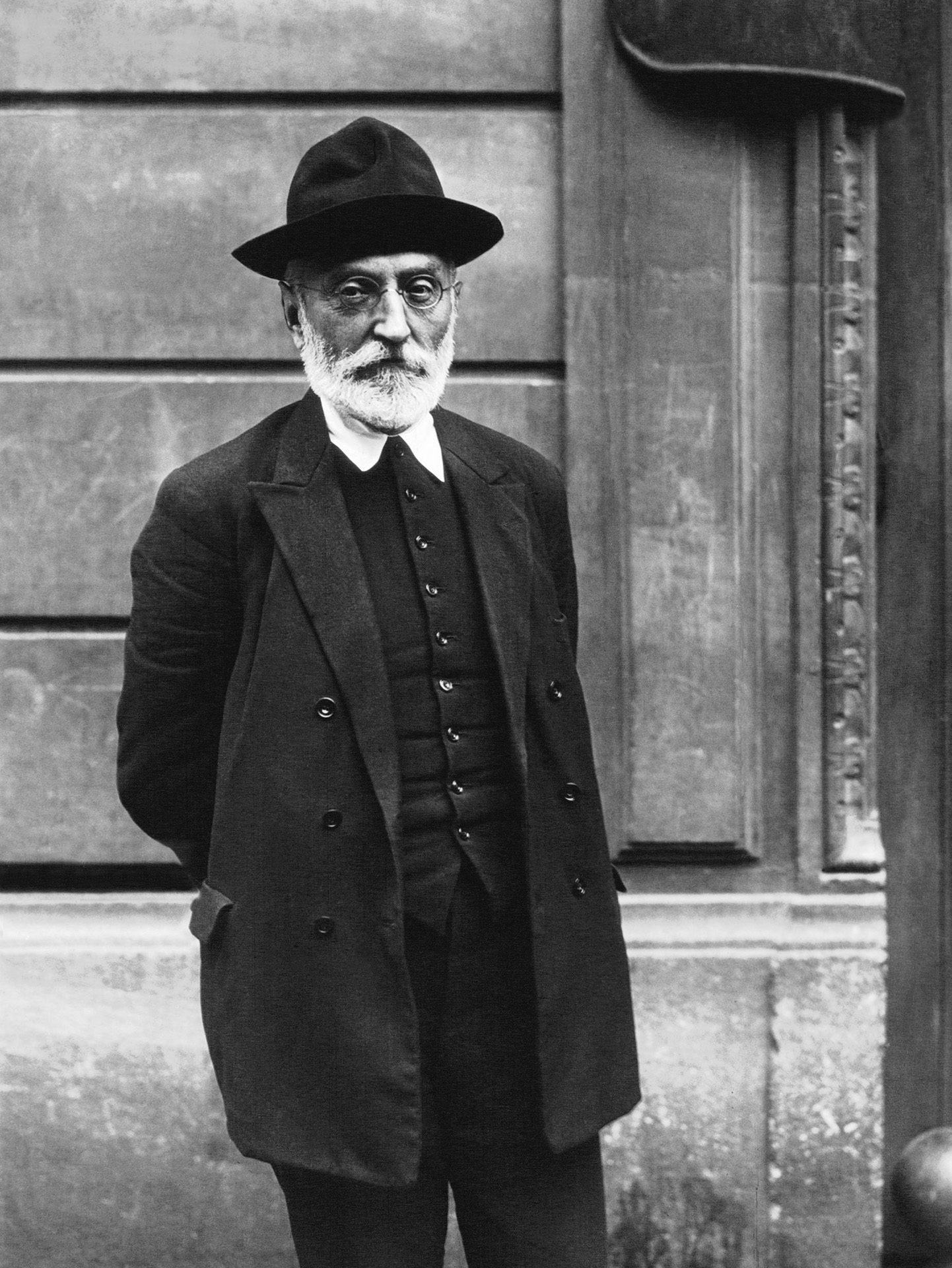

Celebrated philosopher and writer Miguel de Unamuno was an ardent supporter of the Republican cause under the military dictatorship of Primo de Rivera. He took up the struggle against the regime as a moral and political duty. Because of his constant attacks on King Alfonso XIII and the dictator Primo de Rivera he was banished to Fuerteventura, one of the Canary Islands, in 1924, from where he escaped to France. He lived in exile until 1930, the end of Rivera’s regime. He was sixty-six years old when he returned to Spain, and was given a triumphant reception in Salamanca. Furthermore, he was awarded the honor of officially proclaiming the Second Spanish Republic in the Plaza Mayor of Salamanca on April 14, 1931. He also took on a formal political role as a member of the Cortes in the new Republic. However, unhappy with the Republican governments and their weak reforms, Unamuno gradually grew disenchanted with the Second Republic. He became convinced that Spain’s essential qualities would be destroyed if they were too strongly influenced by outside forces. When the Spanish Civil War broke out on July 18, 1936, Unamuno indicated that he would join the cause of the rebels under General Francisco Franco. When a journalist asked how he could side with the military and “abandon a Republic that [he] helped create,” Unamuno responded that it “is not a fight against the liberal Republic, but a fight for civilization. What Madrid represents now is not socialism or democracy, or even communism”. He mistakenly believed in a “pacífica guerra civil-civil” [a peaceful civil war]; but he soon realized that it was going to be a brutal “guerra civil-incivil” [an uncivilized civil war]. After the first murders of intellectuals, including his close friends, he also recognized that the uprising did not intend to renew the Republic, but to restore the Monarchy against which he had fought for so long. In a famous speech he gave on October 12, 1936, during the traditional “Fiesta de la Raza”, he allegedly said to the Falangist General José Millán Astray: “You are waiting for my words. You know me well, and know I cannot remain silent for long. Sometimes, to remain silent is to lie, since silence can be interpreted as assent. […] This is the temple of intelligence, and I am its high priest. You are profaning its sacred domain. You will win [venceréis], because you have enough brute force. But you will not convince [pero no convenceréis]. In order to convince it is necessary to persuade, and to persuade you will need something that you lack: reason and right in the struggle. I see it is useless to ask you to think of Spain. I have spoken.” After this event, Unamuno spent the rest of his days under voluntary house arrest and died in December 1936.

Miguel de Unamuno, c. 1925

bw. photo, exhibition print

Agence de presse Meurisse – Bibliothèque nationale de France

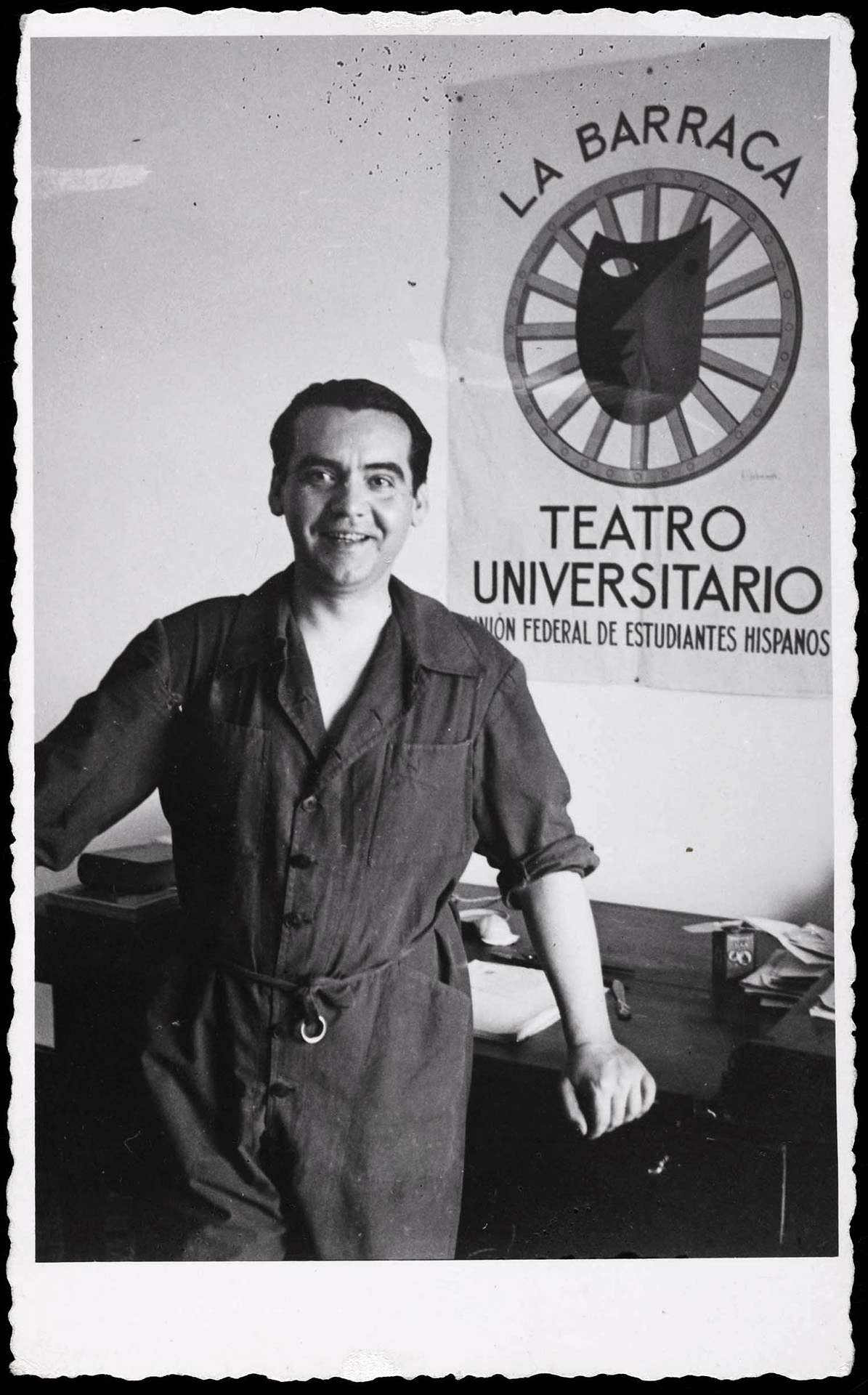

Among the first victims of the civil war was poet and playwright Federico García Lorca. In addition to his literary talent, García Lorca was gifted in almost every field of the arts: he painted, played music, while simultaneously working as a theater director. He studied at the University of Granada in Madrid, and, in the vibrant cultural milieu of the Residencia de Estudiantes, he befriended Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí, and other creative talents of the era. He gained international recognition with Romancero Gitano (Gypsy Ballads, 1928), part of his Cancion [Series] series, with which he also attracted many enthusiasts and followers in Hungary. At the same time, during his successes, the artist’s private life was marked in failures and bitter disappointments. The growing estrangement between García Lorca and his closest friends reached its climax when Dalí and Buñuel collaborated on their 1929 film Un Chien Andalou [An Andalusian Dog]. García Lorca interpreted it, perhaps erroneously, as a vicious attack upon himself. The offended writer traveled to America in 1929, where he studied at the Columbia University, and witnessed the collapse of Wall Street. His return to Spain in 1930 coincided with the fall of the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera and the establishment of the Second Spanish Republic. In 1931, García Lorca was appointed director of a student theatre company, the Teatro Universitario La Barraca [The Shack], which was touring Spain’s rural areas in order to introduce audiences to classical Spanish theater free of charge. While touring with La Barraca, García Lorca wrote his now best-known plays, the “Rural Trilogy” of Bodas de sangre [Blood Wedding], Yerma and La casa de Bernarda Alba [The House of Bernarda Alba], which all rebelled against the norms of bourgeois Spanish society. La Barraca’s subsidy was halved by the right-wing government elected in 1934, and its last performance was given in April 1936. García Lorca was a committed supporter of the Republic—and a well-known liberal public figure—so in the summer of 1936, in an increasingly tense atmosphere he saw fit to move to the countryside. The famous writer arrived in Granada a few days before General Franco’s coup. On August 18, his cousin, the mayor of the city, fell victim to the Francoist militia. García Lorca was also arrested that day and presumably shot dead the next day, near the village of Víznar. The body of the legendary writer was buried in an unmarked mass grave. After Franco’s victory in the civil war, García Lorca’s works were banned for several years, and it was not until 1953 that a carefully examined selection of them appeared. At the same time, Federico García Lorca not only won the respect of the world with his work; he also became regarded as one of the martyrs of freedom and democracy.

Federico García Lorca, Huerta de San Vicente, Granada, 1932

bw. photo, exhibition print

Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid

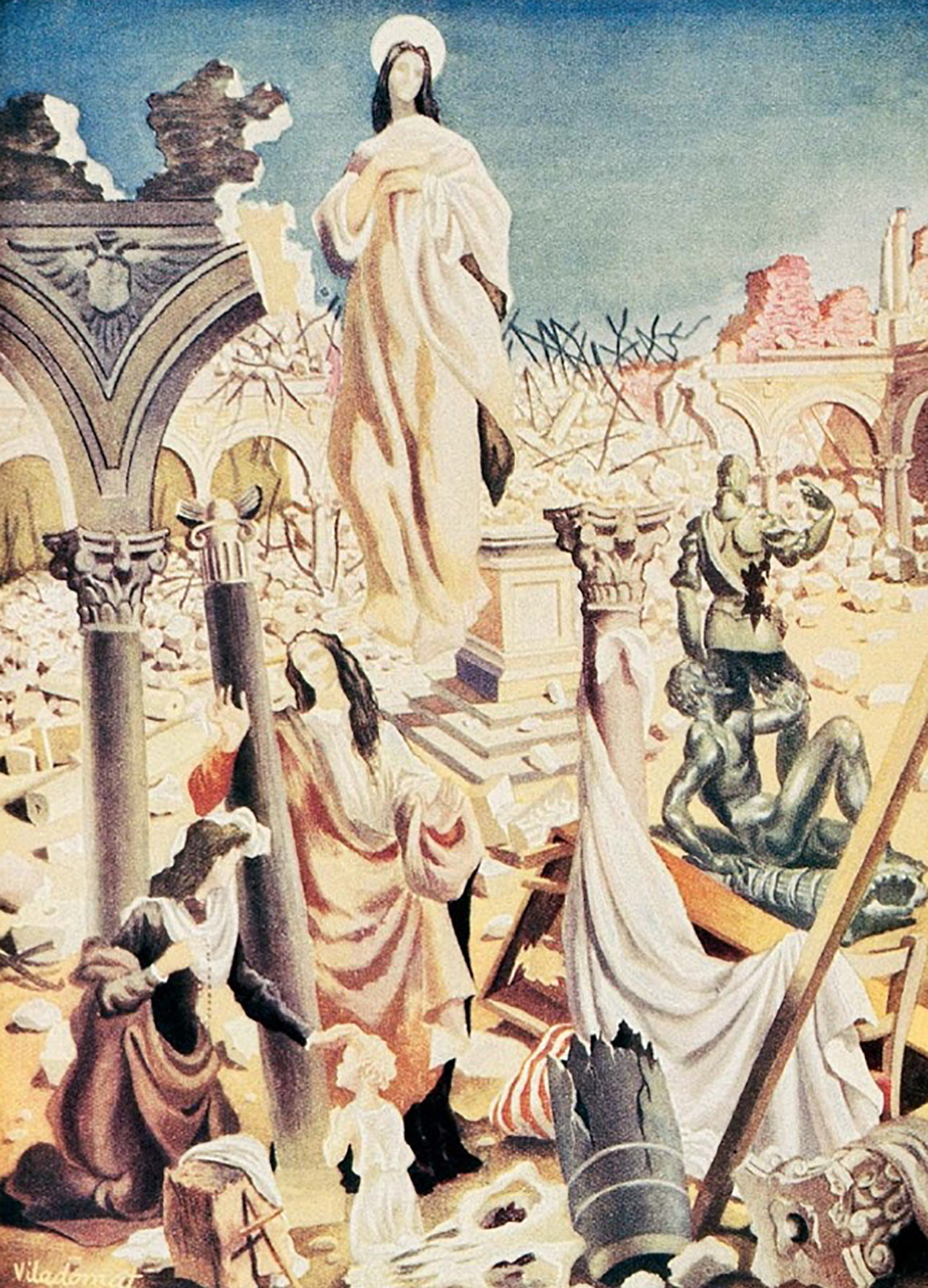

It was not only people who perished during the war. Many historical monuments as well as artworks also fell victim to the violence. In the early days of the civil war, anti-clerical sentiment reached its peak when it became clear that the Francoist uprising was backed by the Church. Churches and monasteries were attacked and set on fire. The Republicans set up militias in order to preserve the artistic and cultural heritage of Spain from radical anticlerical outbursts. The Nationalist propaganda used these attacks against the Republic throughout the civil war, claiming an alleged lack of concern for culture on the Republican side—even though it was the Republicans who organized the protection of artworks of the Prado Museum. An early cultural clash came at the beginning of the civil war, with the siege of the Alcázar in Toledo. This medieval citadel was used as an academy for elite officers, all of whom supported Franco; a group of nationalist soldiers and some civilians took refuge there and successfully sustained a protracted Republican siege during which the famous national monument was subjected to heavy bombing and shelling. By a historical fluke, the supporters of a military coup, the insurrectionists, could thus be depicted as engaged in heroic resistance, and the republican/national opposition appeared in terms of destruction/protection. In the official history of the war written immediately after Franco’s victory, the Alcázar incident featured not only as a chapter of military history but with a special emphasis on the “destruction of the artistic treasure of Toledo”. In a sumptuously illustrated book, the Laureados de España 1936–1939 [Laureates of Spain], in honor of nationalists recipients of the Cruz Laureada de San Fernardo for heroism, slightly surreal imagery was used for its capacity to mythologize the events through visual associations. Domingo Vildomat’s image for the Los héroes del Alcázar [Heroes of the Alcázar] focuses on the destruction of the monument by the Republicans: an accusing El-Greco-like Madonna hovers over the ruins.

David Seymour “Chim” [Dawid Szymin], Arson attacks on churches and monasteries were common during the first days of the civil war. Militias were created in order to preserve the artistic and cultural heritage of Spain from radical anticlerical outbursts. Their mission was to protect churches, museums and libraries. Barcelona 1936

bw. photo, exhibition print

© David Seymour / Magnum Photos

Domingo Viladomat, Los héroes del Alcázar [Heroes of the Alcázar] in the book Laureados de España 1936–1939 [Laureates of Spain], 1939

exhibition print

[Dawn Ades et al, Art and Power. Europe under the Dictators 1930–1945, London: Hayward Gallery, 1995, 102.]

From its founding in 1937, the Falangist publication Vértice was intended to provide a propagandistic image for the side that would eventually be victorious in the Spanish Civil War. One of its early contributors was José Caballero, a friend of Federico García Lorca, who in the mid-1930s was introduced to surrealism through Luis Buñuel, and started to adopt surrealism in his work. The 1936 Francoist coup d’état found him in the part of the country occupied by Franco’s troops. In the words of art historian Jaime Brihuega, “In July 1936, José Caballero was in Huelva, which would soon fall into rebel hands. Caballero’s friendships and activity would cause him to be looked on with suspicion […] [and] the price he had to pay was collaborating with Fascist publications. He drew for the Falangist magazine Vértice and for the collected book Laureados de España [Laureates of Spain]. The works he signed are accompanied by those of D’Ors, Cela, Alfaro, de la Serna, Samuel Ros, Teodoro Delgado, Laín Entralgo, Sáez de Tejada, Neville, Montes, Cunqueiro, Michelena, Correa Calderón, Viladomat and many others. Some acted out of conviction, others out of opportunism and others for survival. But the drama facing Caballero is that of a bloody contradiction. However, it is much more ironic that, paradoxically, Spanish Fascism, which would never succeed in orchestrating a cohesive representative culture, began by expressing itself through images loaded with the most revelatory Surrealism.”

José Caballero, Sin título [Untitled], 1937

gouache on cardboard, exhibition print

Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid

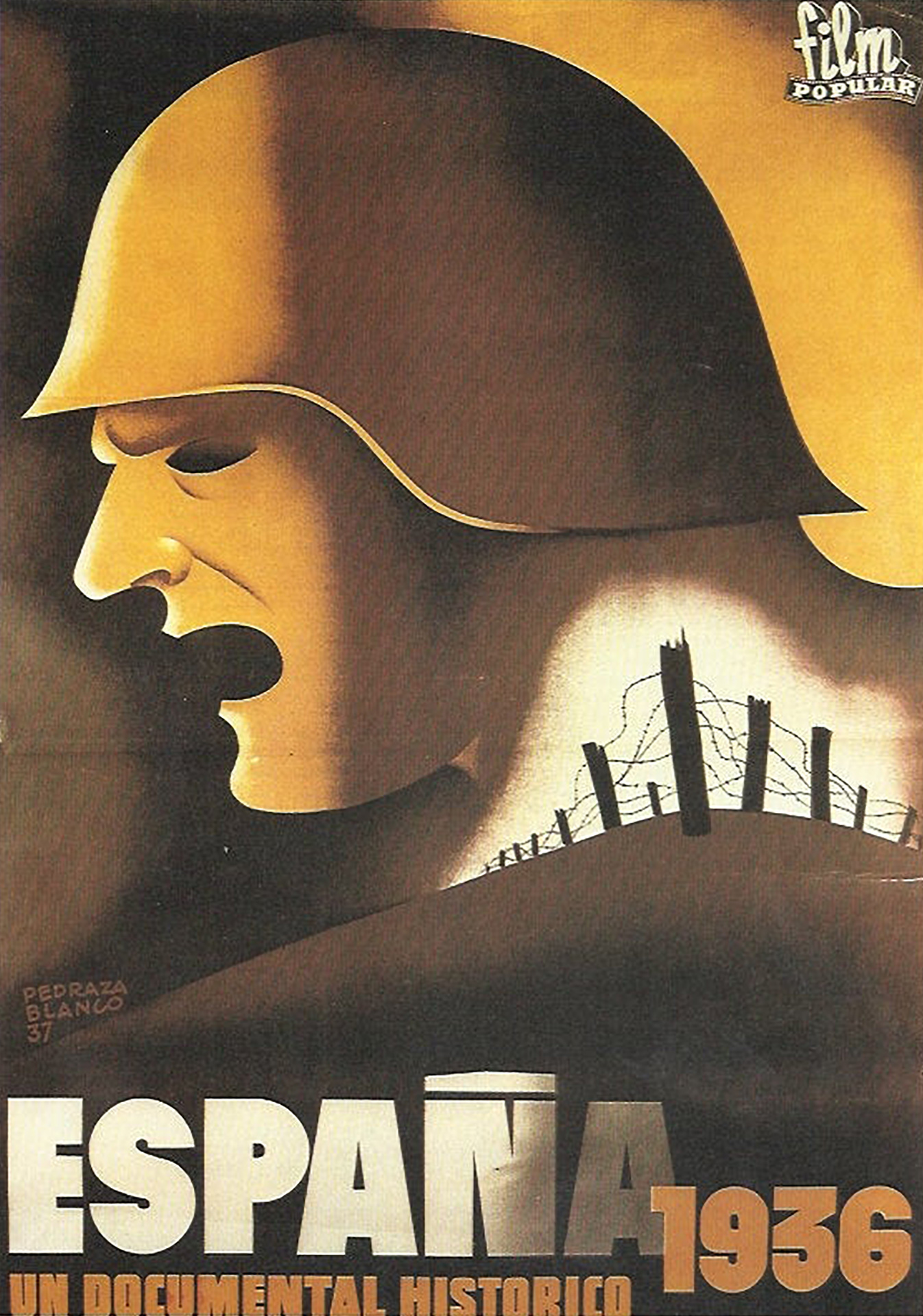

The Republican government established the Ministry of Propaganda in January 1937. This ministry controlled all advertising services and propaganda both in Spain and abroad, and had access to various communication media, including film. One of the film directors working for the Republican cause was Luis Buñuel. Buñuel gained international recognition with his first two films, the gems of surrealist cinema, Un Chien Andalou [An Andalusian Dog, 1928, which he co-directed with Salvador Dalí] and L’Âge d’Or [Age of Gold, 1930]. A few days before the proclamation of the Second Spanish Republic (on April 14, 1931), Buñuel returned to Spain after his years in Hollywood and Paris. His third film, Las Hurdes: Tierra Sin Pan [Las Hurdes: Land without Bread, 1933], was a “surrealist documentary” about life in Las Hurdes, the most backward region in Spain at that time, near the Portugese border, which had been a symbol of medieval backwardness and fathomless poverty, an emblem of “España negra” [Dark Spain] since the 17th century. Las Hurdes was at first banned by the Second Spanish Republic, and premiered only in 1936, under the Frente Popular government when it was praised as “one of the best documentaries in the world.” (The film was again banned during the Franco dictatorship). In 1933, Luis Buñuel voluntarily left the Surrealist movement, and began working for the Filmófono film company, supervising a series of commercial films. The news of the military uprising came as a surprise to Buñuel, who was at the time in Madrid. In his memoirs Mi último suspiro [The Last Breath] he wrote: “Had the outbreak of the war found me in Salamanca (which was one of the first cities to fall to the Fascists), I would certainly have been executed,” referring to the fate of his friends, poet Federico García Lorca and film critic Juan Piqueras Martínez, who were murdered by Fascists. In the summer of 1936, Buñuel signed the Manifesto of the Alianza de Intelectuales Antifascistas para la Defensa de la Cultura [AIDC, Alliance of Anti-Fascist Intellectuals in Defense of Culture]. During the war, he made no attempt to disguise his sympathy for the Spanish Communist Party (PCE), and he was secretly involved in various left-wing political actions. In the Fall of 1936, he was sent to the news service of the Paris embassy as an attaché for the Republican government. There he collaborated on the film España 1936 with French film director Jean-Paul Le Chanois. The film was compiled from a variety of sources: footage recorded by Soviet filmmakers Roman Karmen and Boris Makashev, film newsreel clips and Republican documentaries. Although the film was made with the support of the French Communist Party (PCF), it lacks much of the overt bias common to political documentaries of this time, showcasing the inhumanity, death, and destruction of the Spanish Civil War rather than focusing solely on a political message supporting one side or the other.

Jean-Paul Le Chanois – Luis Buñuel, España 1936, 1937

film poster (design by Pedraza Blanco), exhibition print

wikimedia commons

One of the most famous surrealist painters, Buñuel’s former friend and collaborator Salvador Dalí had a far more genuine relationship with the Franco regime than José Caballero. Dalí was famously accused by André Breton and the Surrealists of defending the “new” and the “irrational” in “the Hitler phenomenon” and was subjected to a “trial” in 1934, in which he narrowly avoided being expelled from the Surrealist group. As some scholars suggest, Dalí’s controversial statement might only “have been motivated by the painter’s desire to offend Breton.” But his relationship with and admiration for Francisco Franco is well-documented: there are many photographs, documents and anecdotes about their friendly rapport. It is also a fact that after the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936, Dalí avoided taking a public stand for or against the Republic, but immediately after Franco’s victory in 1939, he praised Catholicism and the Falange, for which he was finally expelled from the Surrealist group. After his return to his native Catalonia in 1948, he publicly supported Franco’s regime until its end. Yet, in the case of Dalí it is exceedingly hard to separate the statements he made as a public persona—often intended as mere provocations—from his actual views, not to mention his enigmatic and bizarre visual language. In any case, George Orwell, author of Homage to Catalonia (which is based upon his experiences of the Republican militias he joined to fight against Fascism) considers the Dalí-phenomenon in its entirety. “In his outlook,” writes Orwell in the 1944 essay Benefit of Clergy: Some Notes on Salvador Dalí, “his character, the bedrock decency of a human being does not exist. He is as anti-social as a flea. Clearly, such people are undesirable, and a society in which they can flourish has something wrong with it.” However, Orwell was also unwilling to cast aside Dalí’s work. The artist, he writes “has fifty times more talent than most of the people who would denounce his morals and jeer at his paintings.” Orwell, for his part, was definitely taking sides in the matter of Spain, as did many foreign intellectuals who showed their support in many ways, for instance by attending the Second International Congress of Writers for the Defense of Culture, held in the war-torn country in 1937.

Carl Van Vechten, Salvador Dalí in Paris, 1934

bw. photo, exhibition print

United States Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs division

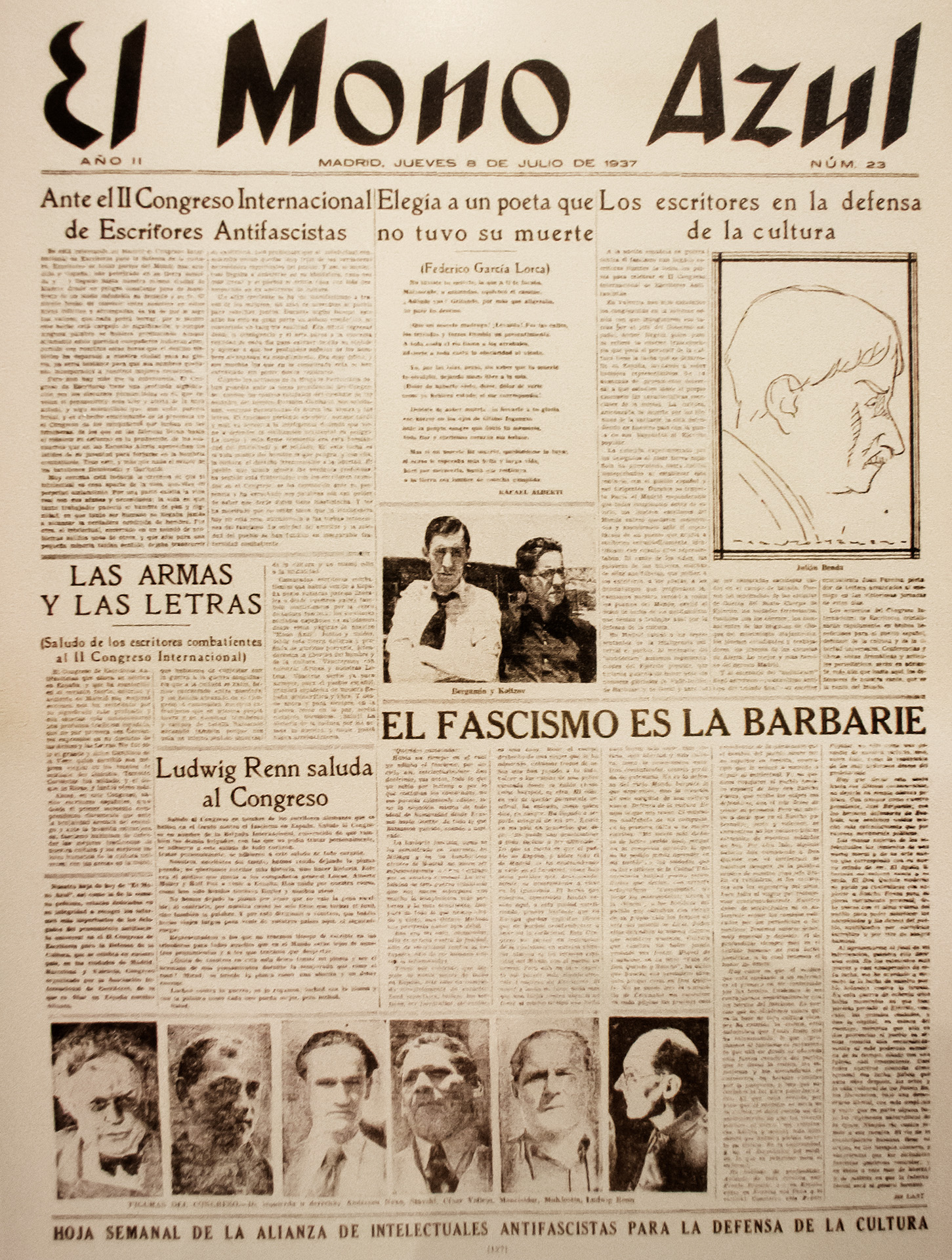

The Alianza de Intelectuales Antifascistas para la Defensa de la Cultura [AIDC – Alliance of Writers for the Defense of Culture] was the Spanish section of the International Association of Writers for the Defense of Culture, and its origin dates back to the First International Congress of Writers for the Defense of Culture, held in Paris between 21 and on June 25, 1935. In June 1936, before the beginning of the Spanish Civil War, the extended Secretariat of this international organization met in London, where the Spanish delegates (Ricardo Baeza and José Bergamín) put Madrid up as a candidate venue for the Second International Congress, to strengthen the bonds between the French and Spanish Popular Fronts. The Spanish AIDC was officially founded after the outbreak of the war; it was set up by writers, artists and intellectuals on July 30, 1936, in order to support the Spanish Republic. Among its members were María Teresa León, Miguel Hernández, Luis Buñuel, Emilio Prados, Josep Renau, and Ramón Gaya. The AIDC had several committees dedicated to different thematic areas and it carried out a great variety of cultural activities, such as series of conferences and publications, the most notorious of which was the magazine El Mono Azul [The Blue Monkey], named after the overalls worn by the militiamen on the war front. Its objective was to reach the soldiers and make them aware of their role in defense of the Second Republic and democracy against Fascism. However, the greatest achievement of the Spanish AIDC was the organization of the Second International Congress of Writers for the Defense of Culture, held between July 4 and 17, 1937, with the participation of numerous Spanish and foreign writers.

The weekly El Mono Azul [The Blue Monkey], July 8, 1937

exhibition print

wikimedia commons

Almost exactly a year after Franco’s uprising against the Second Republic, two hundred writers from about thirty countries—from Algeria to Iceland, from Peru to China—met in major cities in Spain and France to express their solidarity with the Spanish people and their unyielding opposition to Fascism. The fact that the Second International Congress of Writers in Defense of Culture came about was seen as a great moral victory for the Republican government. The Congress, which was organized by the Alianza de Intelectuales Antifascistas para la Defensa de la Cultura [AIDC, Alliance of Anti-Fascist Intellectuals in Defense of Culture], proved what the anti-Fascists had declared over and over again over the previous twelve months: that not a single respected Spanish writer had joined the Nationalist cause (with the exception of Miguel de Unamuno, who, after the military attacks of the Francoist troops, publicly retracted his previous statements). In contrast, many of the most recognized writers and intellectuals in both Europe and America unequivocally expressed their support for Republican Spain, or as it was termed “la república des intelectuales”. The number of delegates and the prestige they enjoyed in the mid-1930s made the Second Writers’ Congress one of the most remarkable events in European literary history in the 20th century. In attendance—among others—were André Malraux and Tristan Tzara from France; W.H. Auden and Edgell Rickword from England; Malcolm Cowley and Anna Louise Strong from the United States; Pablo Neruda from Chile, Raúl Gonzalez Tuñón from Argentina; Carlos Pellicer and Octavio Paz from Mexico; Alejo Carpentier and Nicolas Guillén from Cuba; Ilya Ehrenburg and Aleksey Tolstoy from the Soviet Union; and Bertolt Brecht, Anna Seghers, Lion Feuchtwanger, and Heinrich Mann from Germany (or exile). Beside the official attendees, many other writers were present: Ernst Hemingway allegedly also attended. Although no Hungarian writers were officially listed in the Congress’s program, the poet Miklós Radnóti (who was brutally killed during the Holocaust in Hungary), participated at a Paris meeting of the Congress, as a newly elected member of the Hungarian PEN Club. The Second International Congress of Writers in Defense of Culture was a collective statement of solidarity; yet, as recent scholarly research shows, it was also where the Soviets began to turn the discourse around peace and anti-Fascism into their own shameless propaganda.

Gerda Taro [Gerta Pohorylle], Attendees at the Second International Congress of Writers for the Defense of Culture, Valencia, 1937

bw. photo, exhibition print

International Center of Photography, New York / The Robert Capa and Cornell Capa Archive, Gift of Cornell and Edith Capa, 2010

Robert Capa [Friedmann Endre Ernő], Ernest Hemingway and Ilya Grigoryevich Ehrenburg, Valencia, 1937

bw. photo, exhibition print

International Center of Photography, New York / The Robert Capa and Cornell Capa Archive, Gift of Cornell and Edith Capa, 2010

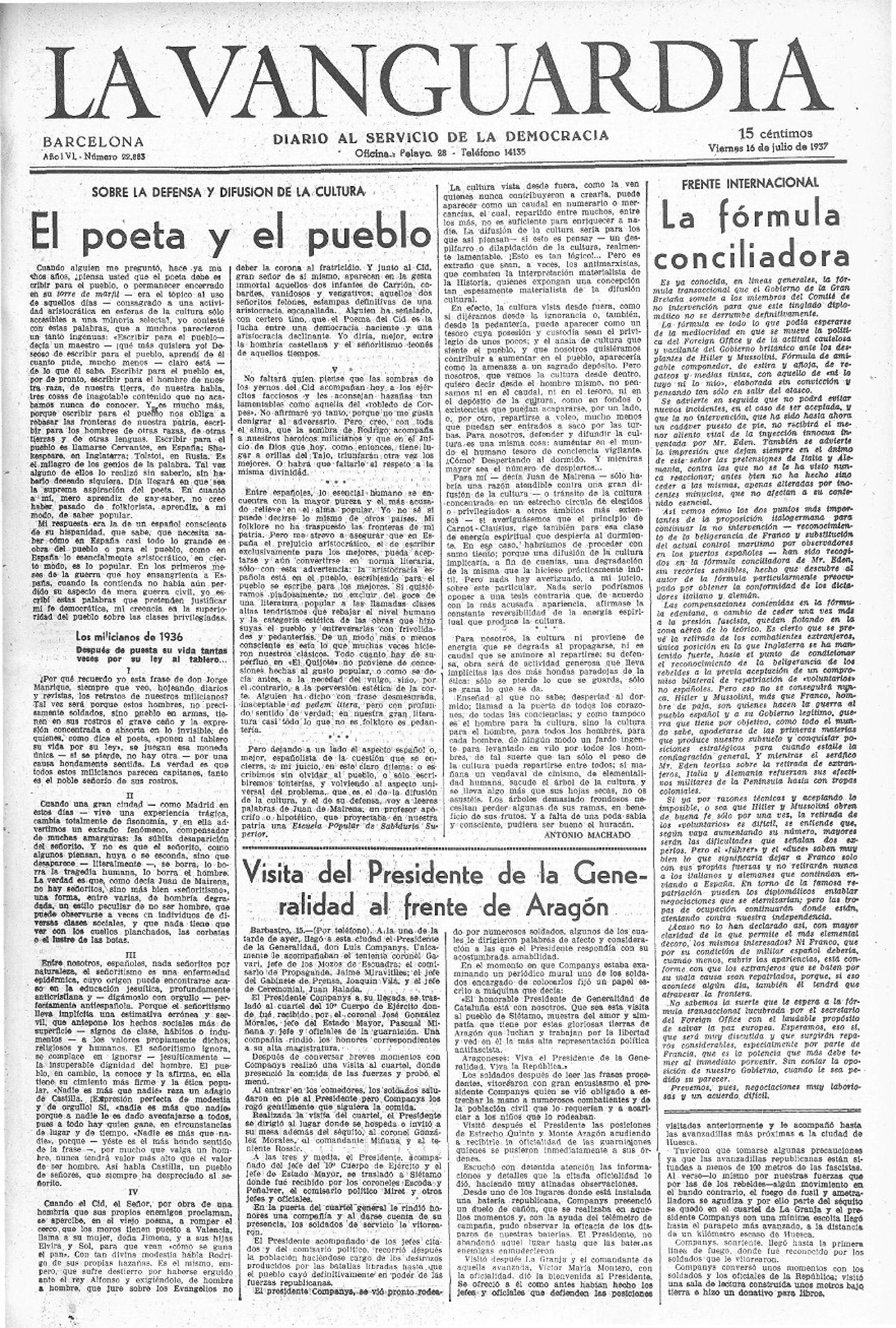

Antonio Machado, a leading figure of the Spanish literary movement known as the Generation of ’98, coined the term of “las dos Españas” [The Two Spains] in a short, untitled poem, number LIII of his Proverbios y Cantares [Proverbs and Songs] in 1917. The term, which refers to the left-right political divisions that later led to the Spanish Civil War, is an example of Machado’s deep understanding of Spain’s common people. From the 1930s, his poems increasingly focused on their collective psychology, social mores, and historical destiny. When Spain erupted in civil war in 1936, Machado initially remained in Madrid. Among many other emergency measures, the Republicans decided to evacuate writers and artists to safer areas, including Machado (due to his advanced age and importance). Machado was evacuated to Valencia in November 1936, which became the second capital of the Republic during the war. In Valencia, he continued to support the Republican cause with his writings and he also attended the Second International Congress of Writers for the Defense of Culture, where he gave the speech El poeta y el pueblo [The poet and the people]. He dedicated the sonnet, A Líster, jefe en los ejércitos del Ebro [To Lister, Chief of the Armies of the Ebro] to Enrique Líster, who was widely regarded as a war hero for the Republican cause: “Si mi pluma valiera tu pistola /de capitán, contento moriría” [If my pen were worth your gun, / Captain, I would happily die.] The volume of his collected poems, Poesías Completas was published in 1938 and contained the cycle Poesias de Guerra [Poems of War], with El crimen fue en Granada [The crime took place in Granada], an elegy to Federico García Lorca. As a strong supporter of the Spanish Republic, Machado fled Spain when the Republic collapsed in early 1939. He died of ill health in the final days of the war, tired and overcome by a long journey into the relative safety offered by France. Although not a direct casualty of the war, like Federico García Lorca, Machado has been heralded since his death as one of the highest-profile victims of the war.

Leonardo Oroz, Portrait of Antonio Machado, 1925

carbon on paper, exhibition print

Fondos de la Fundación Ortega y Gasset, Madrid

El poeta y el pueblo [The poet and the people], a speech by Antonio Machado to the Second International Congress of Writers for the Defense of Culture, 1937

exhibition print

La Vanguardia, July 16, 1937

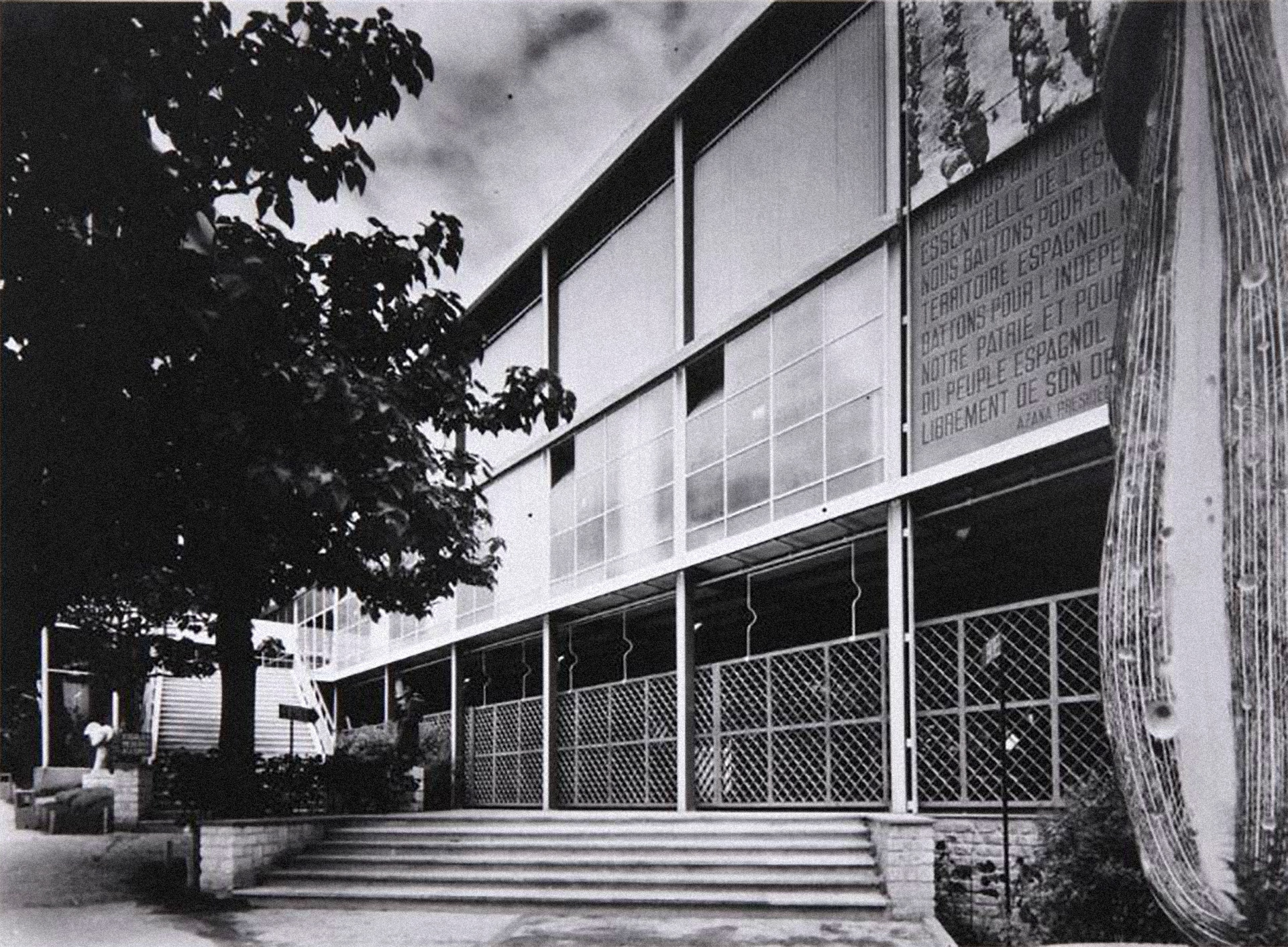

Another major cultural feat of the Republic during the war was its participation in the International Exhibition in Paris in 1937, where the Spanish Republic set up a national pavilion entirely devoted to propaganda. In itself, this would not have been unusual. But instead of displays of industrial and commercial achievements, the Republic chose to represent itself entirely through art and culture. The fact that Spain was in the midst of a civil war with severe disruptions to commerce must to some degree have been responsible for this. The organizers made every effort to show that the government was in control and to counter nationalists claims that Spain had become dangerously destabilized by the Left. They were convinced that a successful participation in such an international event as the Paris Exhibition would raise the standing of the Republican movement and bring tangible benefits in its train. It was the aim of the Spanish Pavilion to draw attention to the ravages of civil war in Spain and to elicit direct support for the Republic. The pavilion was designed by Josep Lluis Sert (the nephew of the painter José María Sert), who was a disciple of Le Corbusier and a founding member of the Catalan rationalist GATCPAC [Grup d’Arquitectes i Tècnics Catalans per al Progrés de l'Arquitectura Contemporània, Catalan Architects and Technicians for the Progress of Contemporary Architecture] group. Sert worked together with Luis Lacasa, who had previously worked for the Republican government on Madrid’s University City project. The pavilion was a light, unostentatious elegant exercise in rationalist architecture. It stood on the main avenue linking the Trocadéro with the Eiffel Tower in the center of the foreign section, where it occupied a highly visible, though relatively small site. Its simple structural exterior was almost self-effacing, in contrast to the attention-seeking German and Soviet pavilions that glared at each other across the approach to the Pont d’Iéna.

François Kollar [Frantisek Kollar/Kollár Ferenc], The Spanish Pavilion at the International Exhibition in Paris, designed by Josep Lluis Sert and Luis Lacasa Navarro, 1937

bw. photo, exhibition print

© RMN-Grand Palais and François Kollar

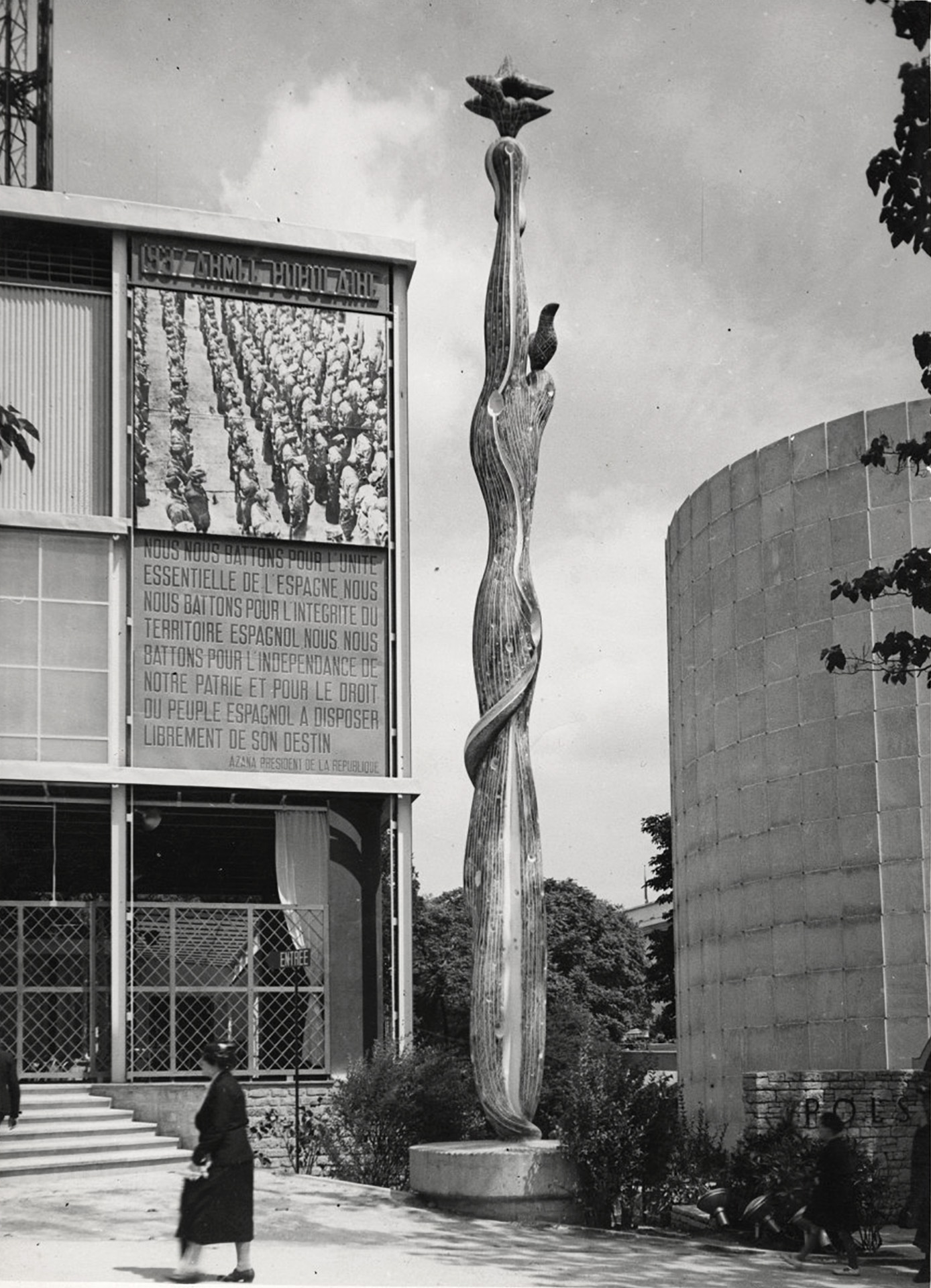

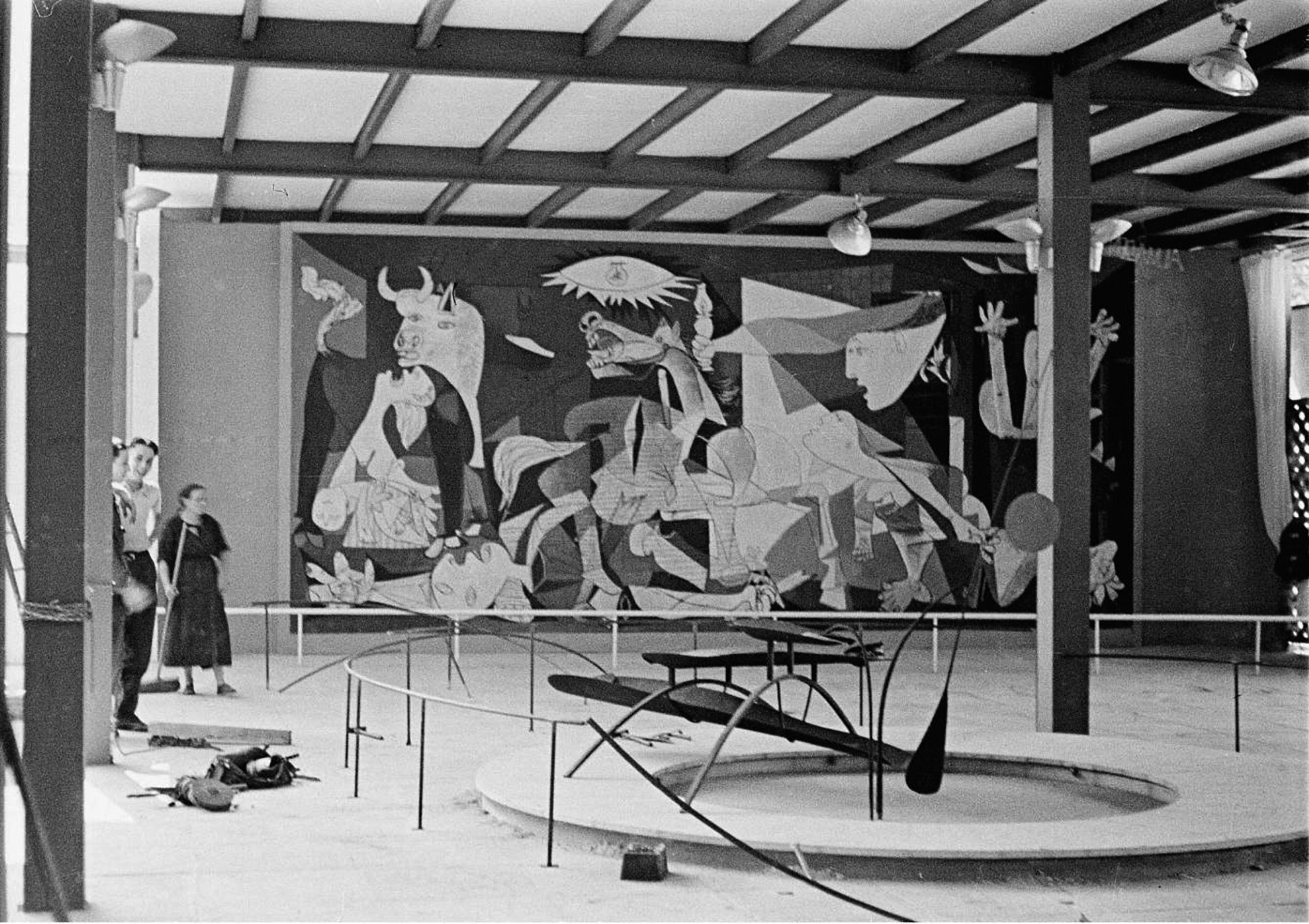

Aesthetically speaking, the Second Spanish Republic had never been so modern as it was at the time of the International Exhibition, just two years before its final defeat. The architects were leading members of the Spanish / Catalan rationalist movement: Josep Lluis Sert and Luis Lacasa Navarro. There were also an array of absolutely unique artistic collaborators, naturally led by Picasso, accompanied by Alberto (Sanchez Pérez), Julio González, Joan Miró and Miró’s American friend, sculptor Alexander Calder, among many other contributors. In the pavilion’s courtyard concerts and dance performances took place, and film shows by Luis Buñuel were held. A fanfare of avant-garde sculpture greeted the visitor. Slightly taller than the building itself, Alberto Sánchez Pérez’s totemic El pueblo español tiene un camino que conduce a una Estrella [The Spanish People Have a Path that Leads to a Star] presided over one side of the entrance area. Picasso’s Woman’s Head, one of five sculptures he showed in the pavilion, stood on the other, with Gonzáles’s Montserrat between them, just to the left of the steps leading up to the main entrance. This impressive display was continued inside the open ground floor, where Alexander Calder’s Mercury Fountain stood opposite to the unquestionable highlight of the pavilion, if not of the whole International Exhibition: the mural painting Guernica, which Picasso had produced especially for this location. The next stage of the tour was the second-floor gallery, reached only by an outside ramp from the courtyard. It started with the fine arts section, which included a plethora of internationally lesser-known Spanish artists, and continued with displays of popular arts and crafts, together with information on the various autonomous regions of Spain. Visitors then descended a flight of stairs, past Joan Miró’s large mural, El segador [The Reaper] to the documentary section on the first floor before leaving the pavilion by another outside staircase that led down to the main front entrance. No object existed solely in its own right: its content, iconography or message was informed or transformed by others in a different medium and in a different part of the building. Victims of the civil war were also commemorated: there was a panel for Federico García Lorca and the sculptors Emiliano Barral and Francisco Pérez Mateo were also remembered. Surrounded by examples of their work with the inscription “Two artists, two heroes of the defense of Madrid” and biographical panels, this section paid homage to the two artists who had died on the Madrid front in 1936.

François Kollar [Frantisek Kollar/Kollár Ferenc], The Spanish Pavilion at the International Exhibition in Paris with Alberto (Sanchez Pérez)’s El pueblo español tiene un camino que conduce a una Estrella [The Spanish People Have a Path that Leads to a Star] in the foreground, 1937

2 bw. photos, exhibition prints

© RMN-Grand Palais and François Kollar

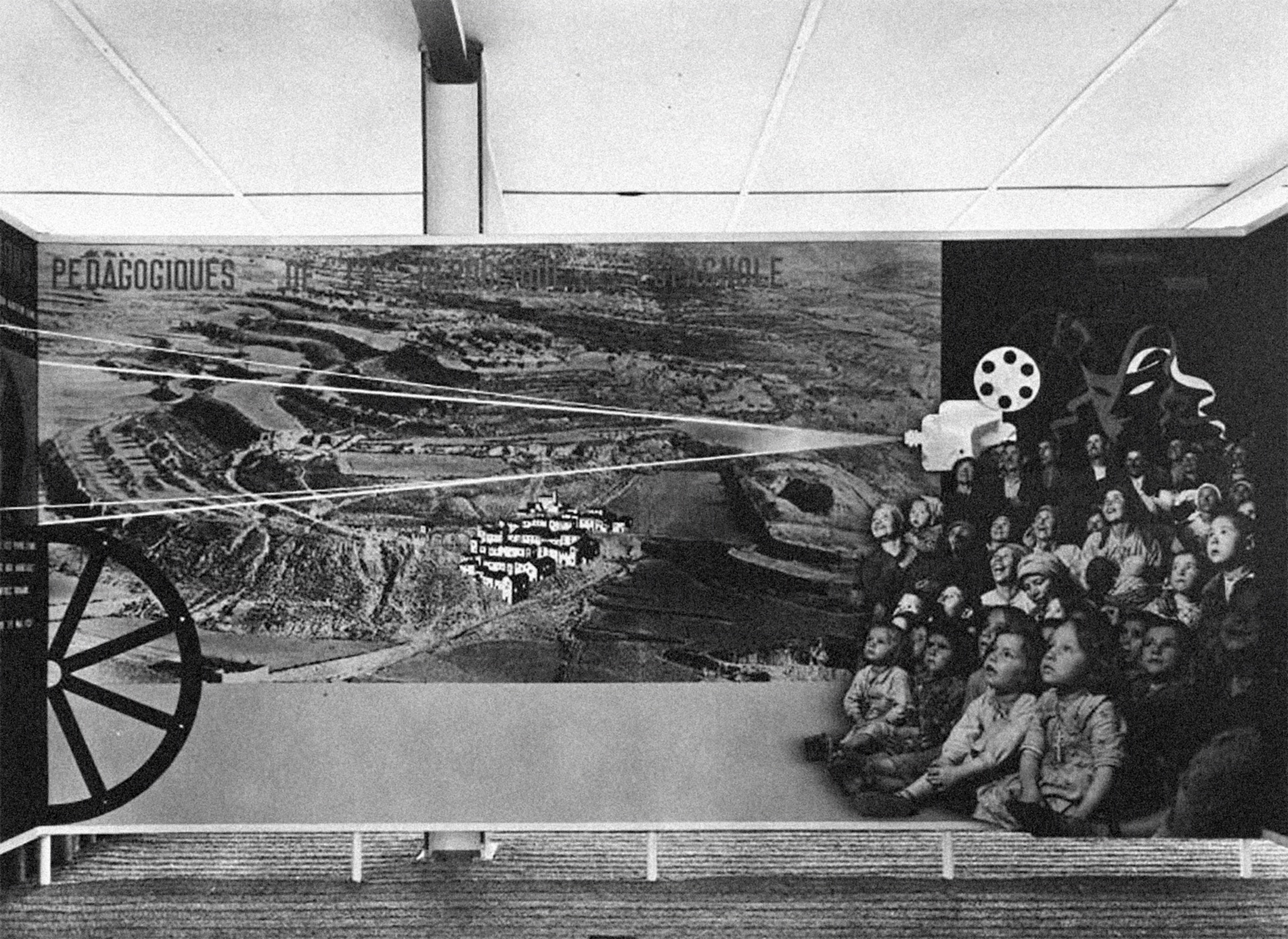

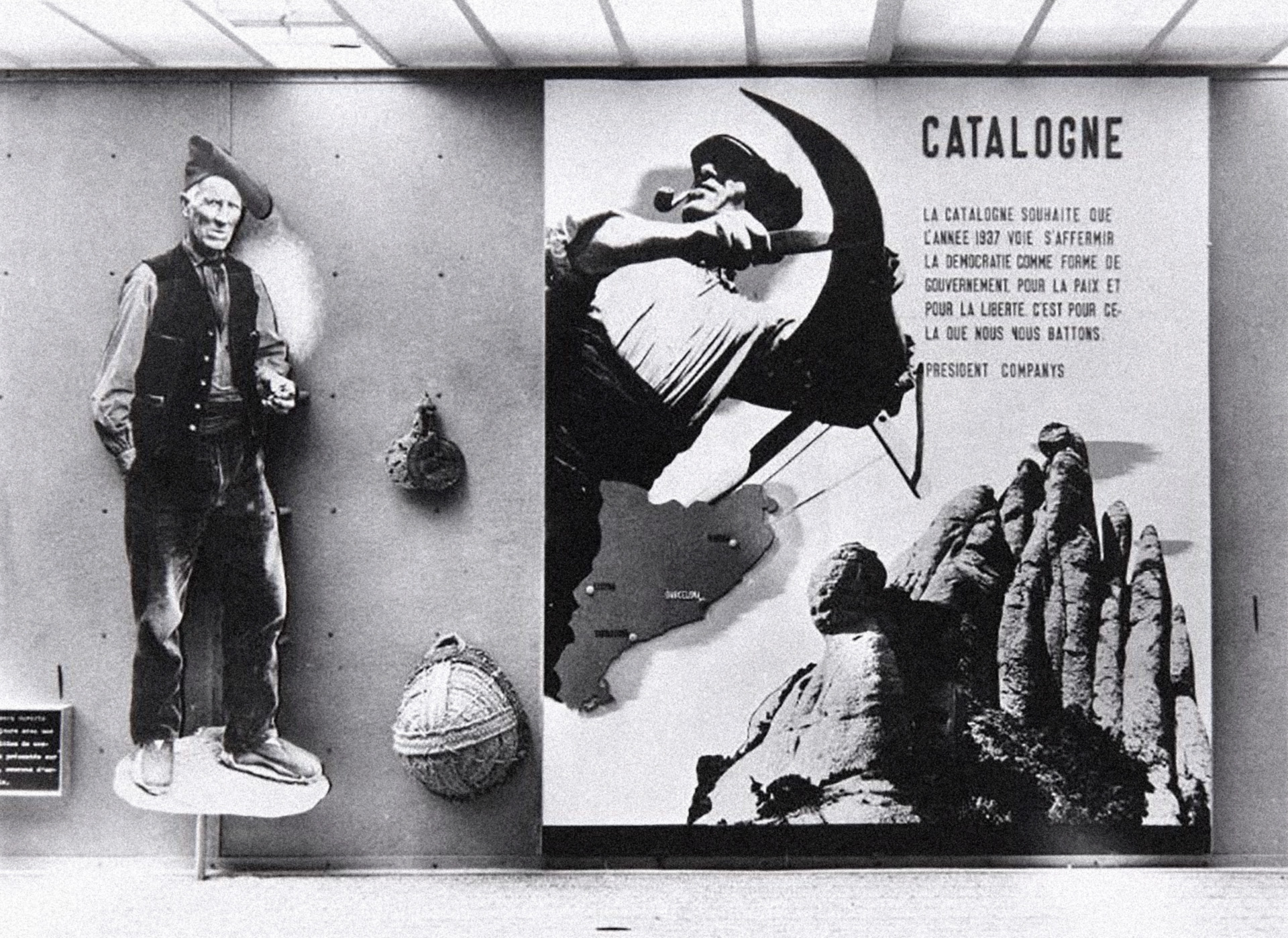

A key element in the pavilion’s scenery was the series of photomontages created by or under the supervision of Josep Renau. Renau, an important figure in the Spanish Communist Party (PCE), was General Director of Fine Arts [Director general de Bellas Artes] from September 1936 onwards. In this position, he appointed Picasso, in a symbolic gesture, as the director of the Prado Museum. During the Second Republic, in his magazine Nueva Cultura [New Culture], and other left-wing media he created a series of political photomontages, and his mastery of the medium, as well as his experience in presenting complex political and social issues in an impressive manner, strongly influenced the displays of the Spanish Pavilion. The panels covered such topics as literacy programs, the provision of schools and hospitals, and help for infants and war widows, as well as the roles of industry and agriculture, and the effects of warfare on Spanish cities. In one of the most striking examples, the role of women in the new society was represented in a photomontage that juxtaposed two life-size images on a “before and after” double panel. The caption left no room for doubt about the changing role of women: “Freeing herself from her wrapping of superstition and misery, from the immemorial slave is born THE WOMAN, capable of taking an active part in the development of the future.” As General Director of Fine Arts, Renau was not only the main commissioner of the Spanish Pavilion, he was also responsible for the evacuation of the Prado Museum. After the Spanish Civil War Renau went into exile in Mexico and later settled in the German Democratic Republic.

François Kollar [Frantisek Kollar/Kollár Ferenc], Photomontages by Josep Renau in the Spanish Pavilion at the International Exhibition in Paris, 1937

3 bw. photos, exhibition prints

© RMN-Grand Palais and François Kollar

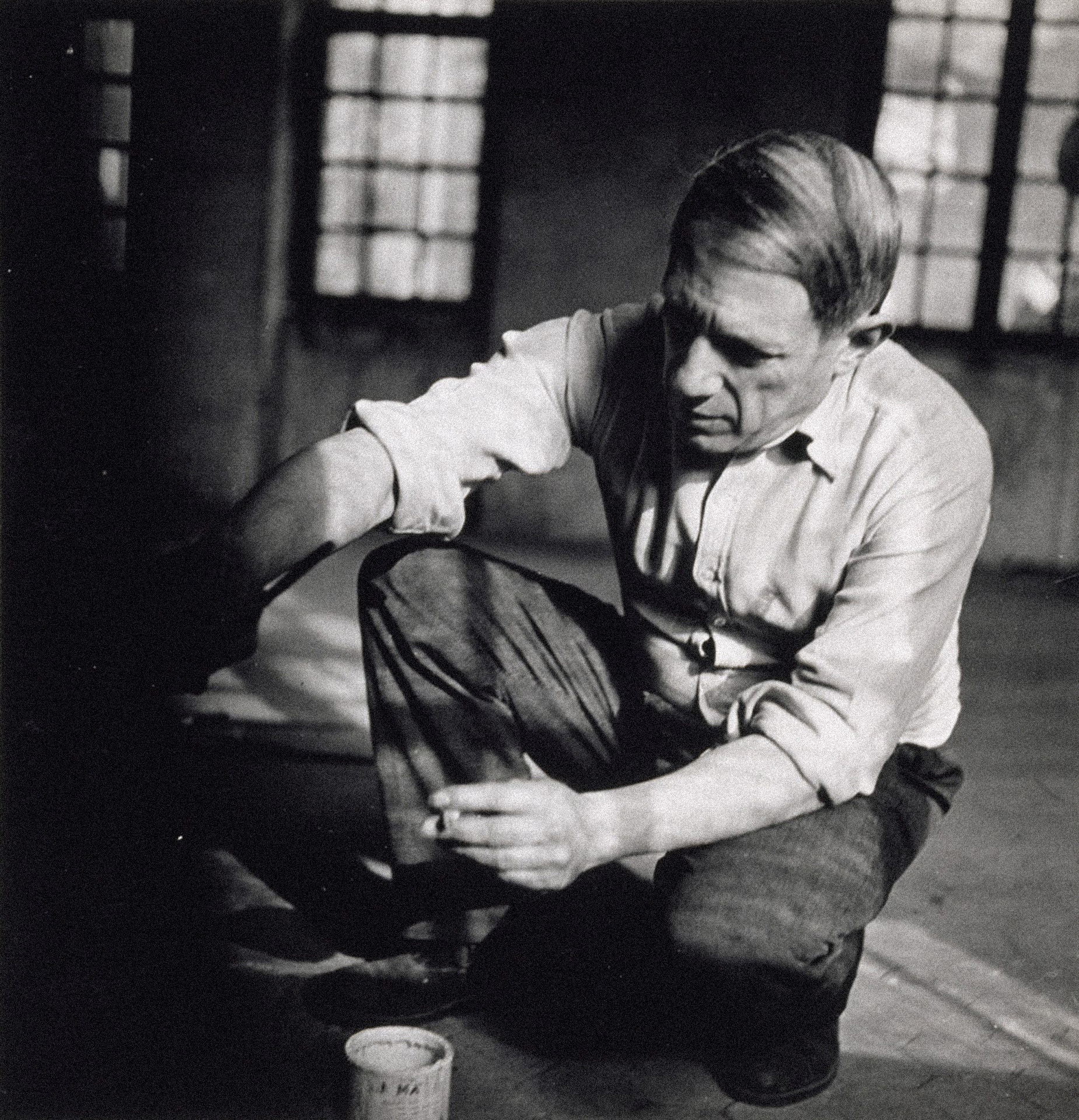

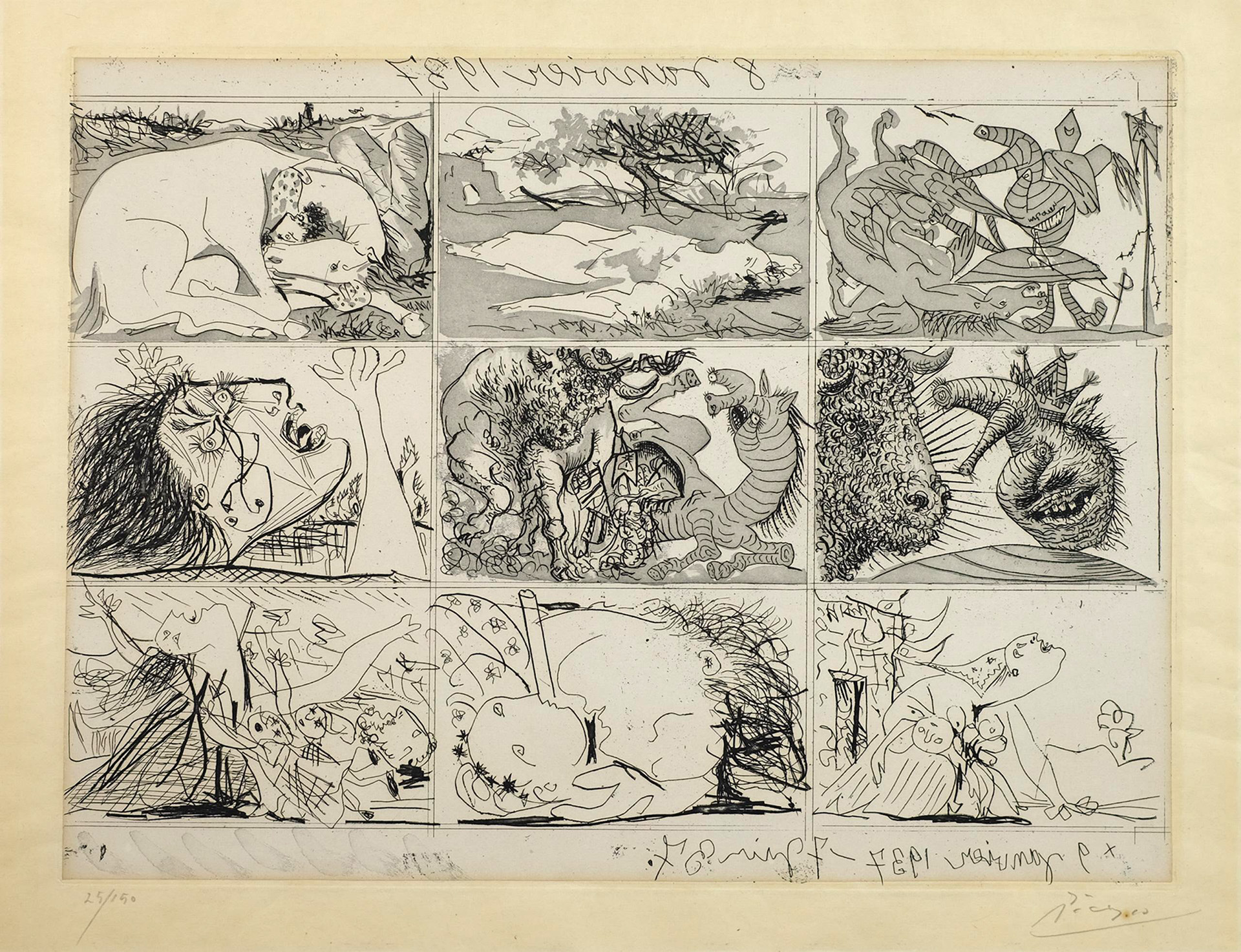

Naturally, the centerpiece of the pavilion was Picasso’s Guernica, inspired by the bombing of the Basque city by the German Condor Legion on 26th April of that year. Guernica became not only a metaphor for the fate of the Spanish Republic, but also a universal symbol for human suffering and a generic plea against the barbarity and terror of war. Picasso painted the monumental canvas in his atelier of the Rue des Grands-Augustins, near the Seine, and the creation process was documented by his partner Dora Maar in a famous series of photographs. The same year, Picasso also contributed to the Republican cause with a set of prints: Sueño y Mentira de Franco [The Dream and Lie of Franco], which is considered to be his first political work. Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, the well-known art historian and art dealer, famously stated in the 1920s, that Picasso was “the most apolitical person I have ever known.” While both Guernica and his prints can be interpreted as universal humanist statements, Picasso gradually became much more open in his political views during the Second World War. Yet, it was a surprise to many of his friends, when he joined the French Communist Party (PCF) in 1944. Moreover, he not only joined but also played an active role in the international Communist movement for about ten years. He supported the French labor movement, created the symbol and participated in the world meetings of the so-called Peace Movement. In 1950 he even received the Stalin Peace Prize from the Soviet government. While his political involvement caused many controversies, Guernica remained among the classic works of art of the 20th century. After the closure of the 1937 International Exhibition, the painting was sent on a money-raising tour round Britain and the United States, and remained “in exile” in the Museum of Modern Art in New York until 1981, when, after the death of Franco and the end of his regime it finally returned to Spain.

Dora Maar [Henriette Theodora Markovitch], Picasso working on Guernica, 1937

bw. photo, exhibition print

Musée National Picasso—Paris / ©RMN-Grand Palais, Mathieu Rabeau and Succession Picasso

Pablo Picasso [Pablo Ruiz Picasso], Sueño y Mentira de Franco II [The Dream and Lie of Franco II], 1937

aquatint, exhibition print

© Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

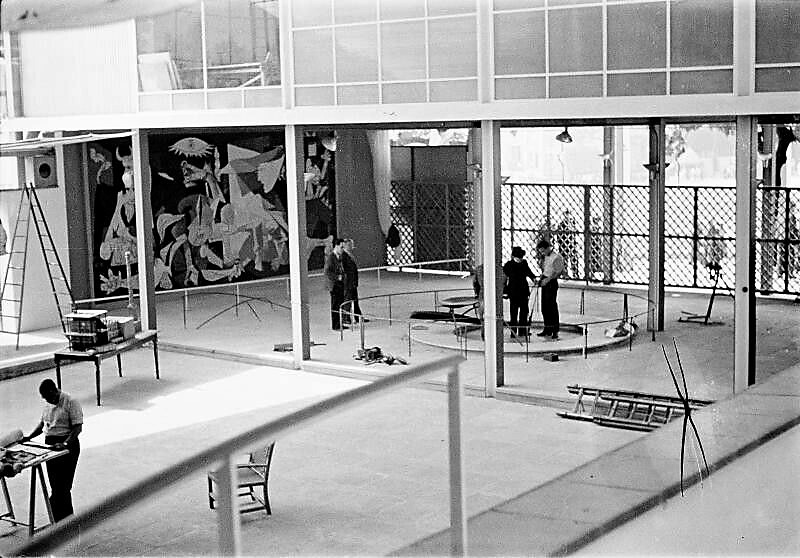

François Kollar [Frantisek Kollar/Kollár Ferenc], Picasso’s Guernica displayed in the Spanish Pavilion at the International Exhibition in Paris, with Alexander Calder’s Mercury Fountain in the foreground, 1937

bw. photo, exhibition print

© RMN-Grand Palais and François Kollar

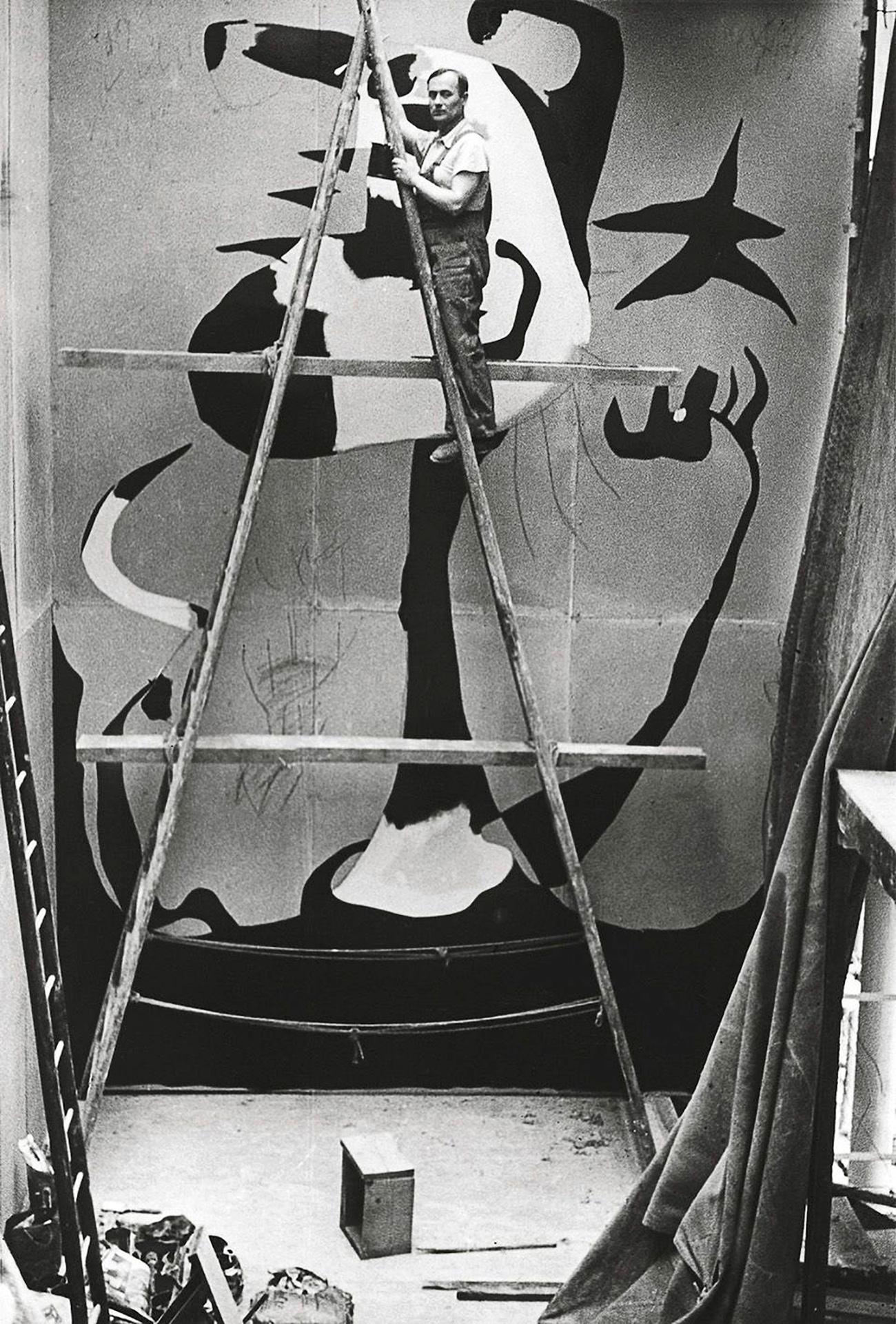

In 1937, at the height of the Spanish Civil War, several Spanish artists were commissioned by the Republican Government to make works for the International Exhibition in Paris. Joan Miró created in situ an extraordinary 5.5-meter high anti-war mural called El segador [The Reaper], also known as El campesino catalán en rebeldía [Catalan peasant in revolt] on the pavilion’s staircase. Miró moved with his family to Paris in 1936 to escape the Spanish Civil War. Until 1937 he had maintained a mostly apolitical stance, but he had Republican sympathies, and the mural was intended as a protest against the violence wracking his home country. He had created a stamp and poster, Aidez l’Espagne [Help Spain], earlier in 1937, which depicted a Catalan peasant wearing a traditional red hat [barretina] and shaking his fist. The peasant had been used as a symbol of Catalan nationalism since the 17th century, and was a theme in Miró’s work since the 1920s. The same figure appears in The Reaper, also wearing a barretina—a potent symbol of Catalan identity and a sign of subtle resistance (the hat had previously been banned) that cleverly combined popular symbolism with a political message. Miró’s work was inspired by a Catalan song, “Els Segadors” [The Reapers], which eventually became Catalonia’s national anthem. Along with Picasso, Miró felt passionately about the opportunity to express his support of his people’s plight: “Of course I intended it as a protest,” he said. “The Catalan peasant is a symbol of the strong, the independent, the resistant. The sickle is not a communist symbol. It is the reaper’s symbol, the tool of his work, and, when his freedom is threatened, his weapon.” He described the act of painting The Reaper in urgent tones that reflected his passion: “I painted on a scaffolding directly in the very space of the building. I first made a few light sketches to know vaguely what I needed to do, but… the execution of this work was direct and brutal.” After the exhibition closed in November 1937, the mural was dismantled along with the rest of the pavilion in early 1938. Miró donated the mural to the Spanish government, and the six panels were packed to be transported to the Ministry of Fine Arts in Valencia, but they were subsequently lost or destroyed, and the painting survives only in a few black and white photographs.

Joan Miró working on his mural El segador [The Reaper], in the Spanish Pavilion at the International Exhibition, Paris, 1937

bw. photo, exhibition print

© Clovis Prévost, Hédouville

Julio González, a friend of Picasso from his symbolist Barcelona days at Els Quatre Gats, who was also residing in Paris at the time, presented the sculpture Montserrat outside the pavilion on the ramp. Started as a piece about motherhood, the sculpture later gained political significance as a result of the Spanish Civil War. The title is a reference to the mountain of Montserrat near Barcelona, a traditional symbol of the sculptor’s native Catalonia. González, who came from a family of workers in precious metals, was taught to work with metal at an early age and later learned industrial welding at the Renault factory. González pioneered welding techniques in sculpture and also guided Picasso decisively in the field of wrought-iron sculpture. His works came to reflect his pessimistic reaction to the war. “It is high time that this metal ceased to be a murderer and the simple instrument of an overly mechanical science. Today, the door is opened wide for this material to be—at last!—forged and hammered by the peaceful hands of artists.” Montserrat is a symbol of universal pain; a sublime work that is more figurative and dramatic than González’s other works; a personal way for its author to reconcile his Cubist heritage with his bitter sentiments over the fate of Spain.

Julio González, Montserrat, 1937

welded and wrought iron, wood; photo reproduction

Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam © Pictoright Amsterdam / Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam

Officially the Republic was the sole representative of the Spain at the International Exhibition, as the Nationalists’ rival government was not recognized by the international community. Given the Nationalists’ fusion of politics and religion, it comes as no surprise that the Vatican provided Franco’s side with an opportunity to participate. The Pontifical Pavilion in the foreign section, just behind the Spanish Pavilion, included votive altarpieces offered by various countries. Among them in the center of the apse was José María Sert’s [Josep Maria Sert] painting Intercesión de Santa Teresa de Jesús en la Guerra Civil Española [An Intercession by Saint Teresa of Jesus in the Spanish Civil War]. (Sert was the uncle of the architect of the Spanish Pavilion, Josep Lluis Sert.) The monumental canvas, often referred to as the “Francoist Guernica”, was commissioned by Cardinal Isidro Gomá y Tomás, though it was presented as a national contribution. (Cardinal Gomá, the Archbishop of Toledo, as the Primate of Spain wrote an open letter to Catholics worldwide legitimizing the Nationalists’ insurrection as a battle against an atheist revolution in 1937). The painting depicts a crucified Christ hovering overhead: with one hand, which he has freed from the cross, he clasps the upraised arm of an earthbound Saint Teresa, who in turn embraces with her other arm a Spanish bishop, the first in a long line of “martyrs” that snakes down to a burning cathedral in the background of the painting. The edifice in question was the Vic Cathedral [Catedral de Vic, Catedral de Sant Pere Apòstol], which Sert himself decorated before the civil war, and which was badly damaged in July 1936 when a band of Republican sympathizers vented their anger at the Church’s role in the Nationalist uprising by going on a rampage. Though never deeply committed, Sert had previously supported liberal politics. Yet, in mid-1937 he presented himself at the Nationalist headquarters in Burgos offering his services. The explanation for this sudden change of heart was most probably the artists’ outrage at the destruction of his lifelong project. He went back to Vic to repaint the cathedral as soon as it was possible and devoted the final years of his life until 1945 on this task.

The Pontifical Pavilion at the International Exhibition in Paris, 1937

bw. photo, exhibition print

Mercury NGA Library, Washington

José María Sert [Josep Maria Sert], Intercesión de Santa Teresa de Jesús en la Guerra Civil Española [An Intercession by Saint Teresa of Jesus in the Spanish Civil War], sketch for the monumental painting presented in the Vatican Pavilion at the International Exhibition, 1937

oil on canvas glued to board, exhibition print

Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid

As Guernica continued on its way to fame and exile in the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Franco prepared to send prisoners of war to build a giant monument: la Santa Cruz del Valle de los Caídos [The Holy Cross of the Valley of the Fallen]. The Valley of the Fallen lies near the battlefield which was immortalized by Hemingway in the novel For Whom The Bell Tolls. The monument, considered a landmark of 20th-century Spanish architecture, as well as one of the most controversial historical sites of Spain, was planned as an homage to the fallen Nationalist soldiers of the “glorious crusade”. At the same time, the Valley of the Fallen was meant to be, according to Franco, a “national act of atonement” and reconciliation. It was designed by Pedro Muguruza and Diego Méndez on a scale to equal “the grandeur of the monuments of old, which defy time and memory.” They revived the sepulchral style of 16th-century Spanish architect Juan de Herrera, but the edifice is also reminiscent of Albert Speer’s monumental style. Although it was not Franco’s intention, his remains were buried in the Basilica of the Valley of the Fallen, and remained there until 2019, when they were exhumed and reburied in the Mingorrubio-El Pardo municipal cemetery, as a result of efforts to eradicate all public veneration of his dictatorship.

Francisco Franco (center) at the inauguration of the Valley of the Fallen, Madrid, April 1959

bw. photo, exhibition print

Agencia EFE