Bertolt Brecht set out in 1935 on his first voyage to America. He sailed on a grubby, if not black, freighter, from Denmark, where he had spent several years in exile from Hitler’s Germany. His destination was New York and the opportunity to collaborate in a production of the “Lehrstück” [“play for learning”] Die Mutter [The Mother], which was based on the novel by Maxim Gorky, at the Theater Union. The production, however, did not go according to Brecht’s plans, because the ensemble was not open to his concept of an “Epic theater”, and Brecht returned to Europe with a bitter taste in his mouth. The same year, he attended as an exiled German writer the First International Congress of Writers for the Defense of Culture at the Palais de Mutualité in Paris. The Congress was a rallying point for European intelligentsia in the fight against Fascism, and the literary world’s response to the slogan of the “Popular Front”, which was heralded during the 7th Congress of the Communist International. Despite the defining influence of the Soviet delegates and other Communist writers, it was the first congress in history where the notion of cultural freedom and the danger of totalitarianism were so widely debated. In reality, the desire for unity among left-wing organizations preceded the Comintern’s new policy, and it was based on the fact that Fascist and Nazi ideas spread rapidly in almost all countries of Europe and beyond. It was also based on the fear of a new war which, by the mid-1930s, seemed closer than ever. The rearmament of the Germans—in spite of the resolutions of the Treaty of Versailles—as well as Italy’s war in Abyssinia clearly showed that the highly complex alliances and pacts between the powers of Europe would not guarantee peace.

Brecht fled from the war in 1941 to the United States. Along with the exiles fleeing from the Nazi regime, the ideological battles of Europe also reached America. The 1930s was a period of massive pro-working-class social reforms and of a mass socialist presence among working people in the United States. The New Deal policy of the Roosevelt government did not only manifest in different federal agencies that tried to improve the lives of people suffering under the Great Depression and the ecological catastrophe of the Dust Bowl. It also set up various programs to provide work relief for artists in various media, and it also commissioned artists to document the hardships of the Americans during the Great Depression. The artists also formed unions and other organizations to fight for their rights and for artistic freedom, and many of them also joined the fight against Fascism.

After the Second World War, in the years of the Cold War and “Red Scare”, Brecht was summoned to appear in front of the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) in 1947. Much to the surprise of the HUAC, Brecht had never been a member of the Communist Party. He was exposed not as a Communist, but rather as a curiously elusive writer and critic who had championed the right to aesthetic freedom and political dissent throughout his career. His aesthetic legacy is perhaps best represented in the conclusion to the statement that he presented during his hearings, which in no uncertain terms defends the necessity of art for the cause of freedom: “My activities, even those against Hitler, have always been purely literary activities of a strictly independent nature… I feel free for the first time to say a few words about American matters: looking back at my experiences as a playwright and a poet in the Europe of the last two decades, I wish to say that the great American people would lose much and risk much if they allowed anybody to restrict the free competition of ideas in cultural fields, or to interfere with art, which must be free in order to be art.”

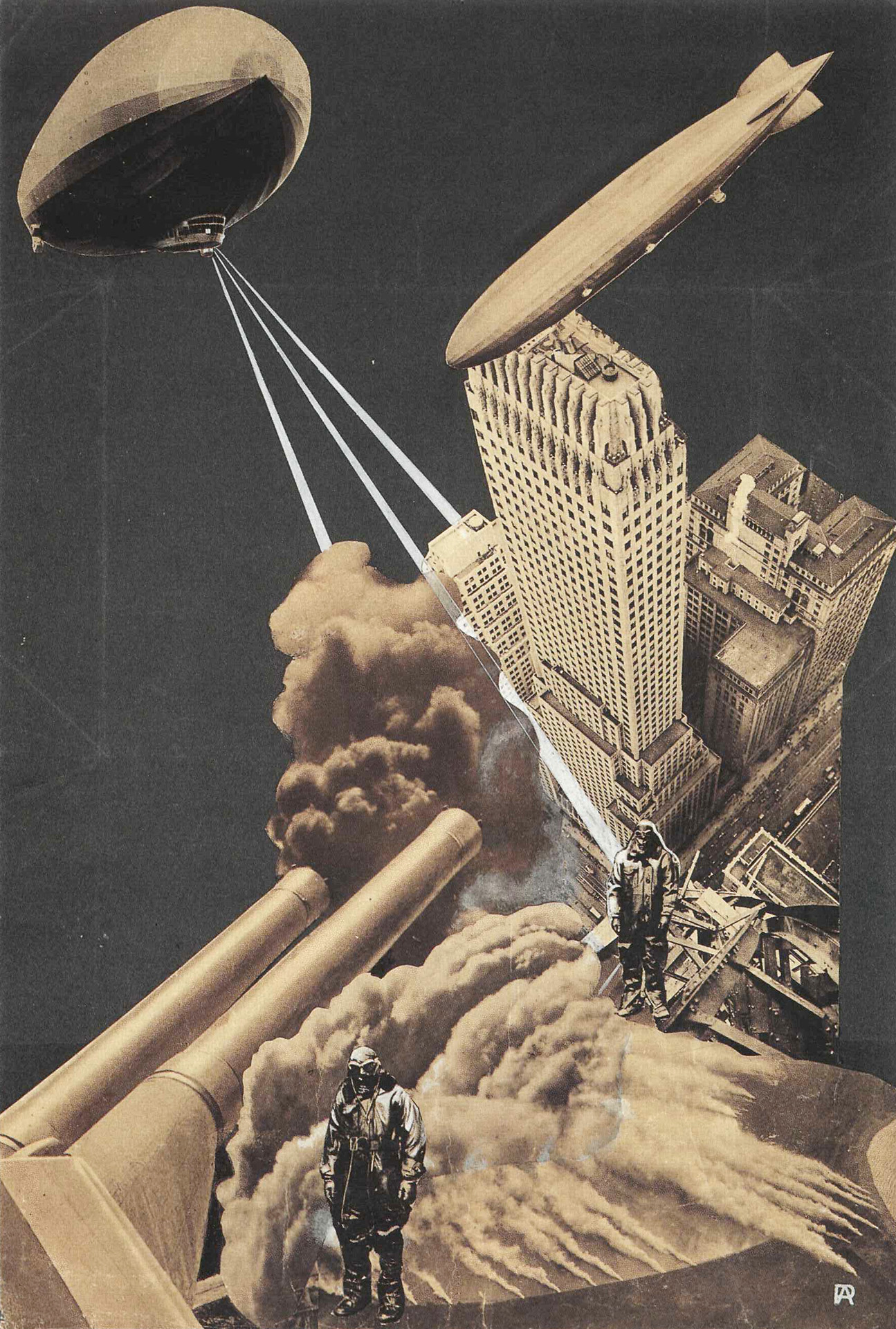

Aleksander Rodchenko, Война будущего [War of The Future], 1936

photomontage, exhibition print

The Rodchenko and Stepanova Archive, Moscow

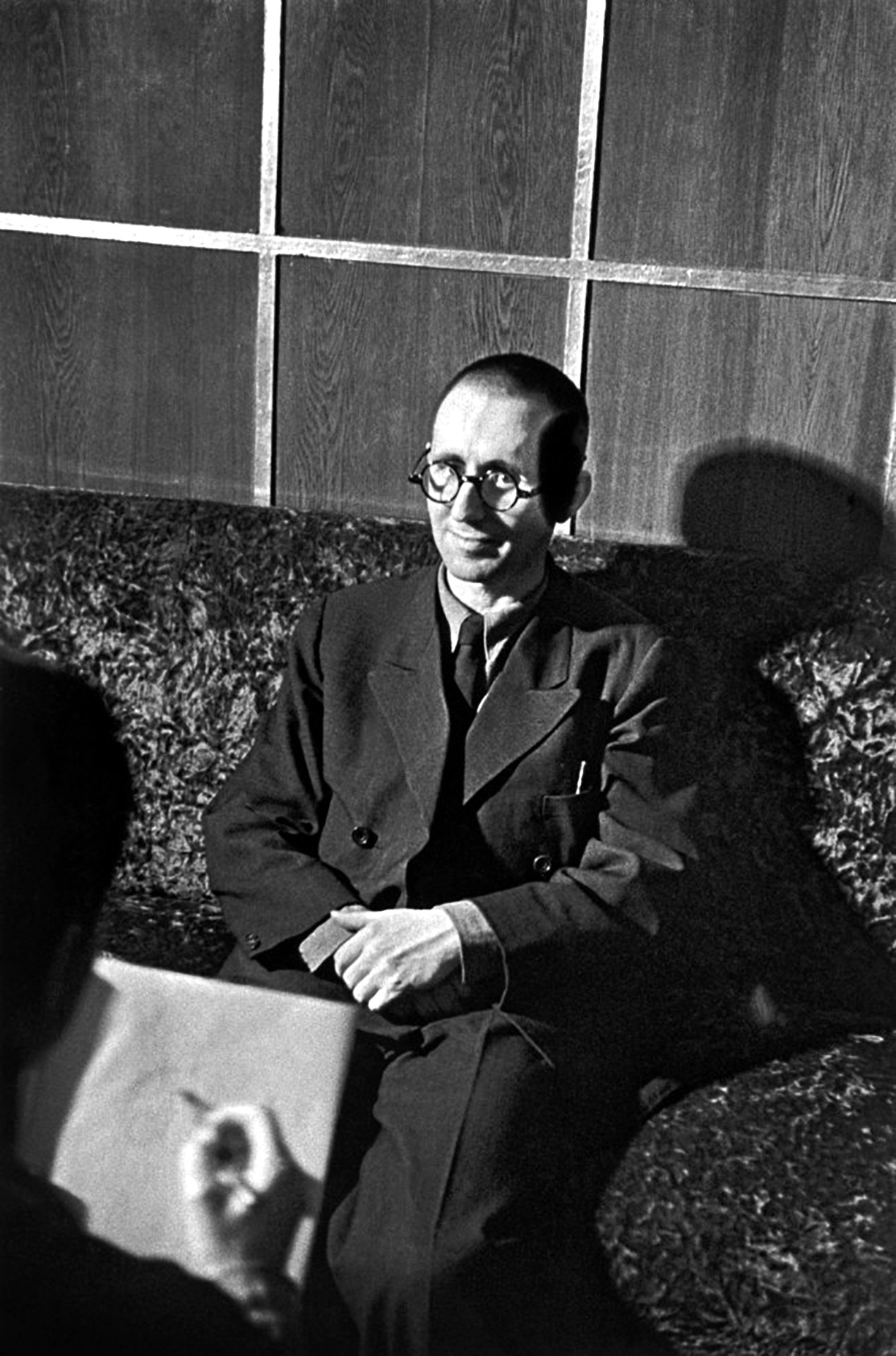

Gisèle Freund, Bertolt Brecht at the First International Congress of Writers for the Defense of Culture at the Palais de Mutualité, Paris, France, 1935

bw. photo, exhibition print

© Gisèle Freund

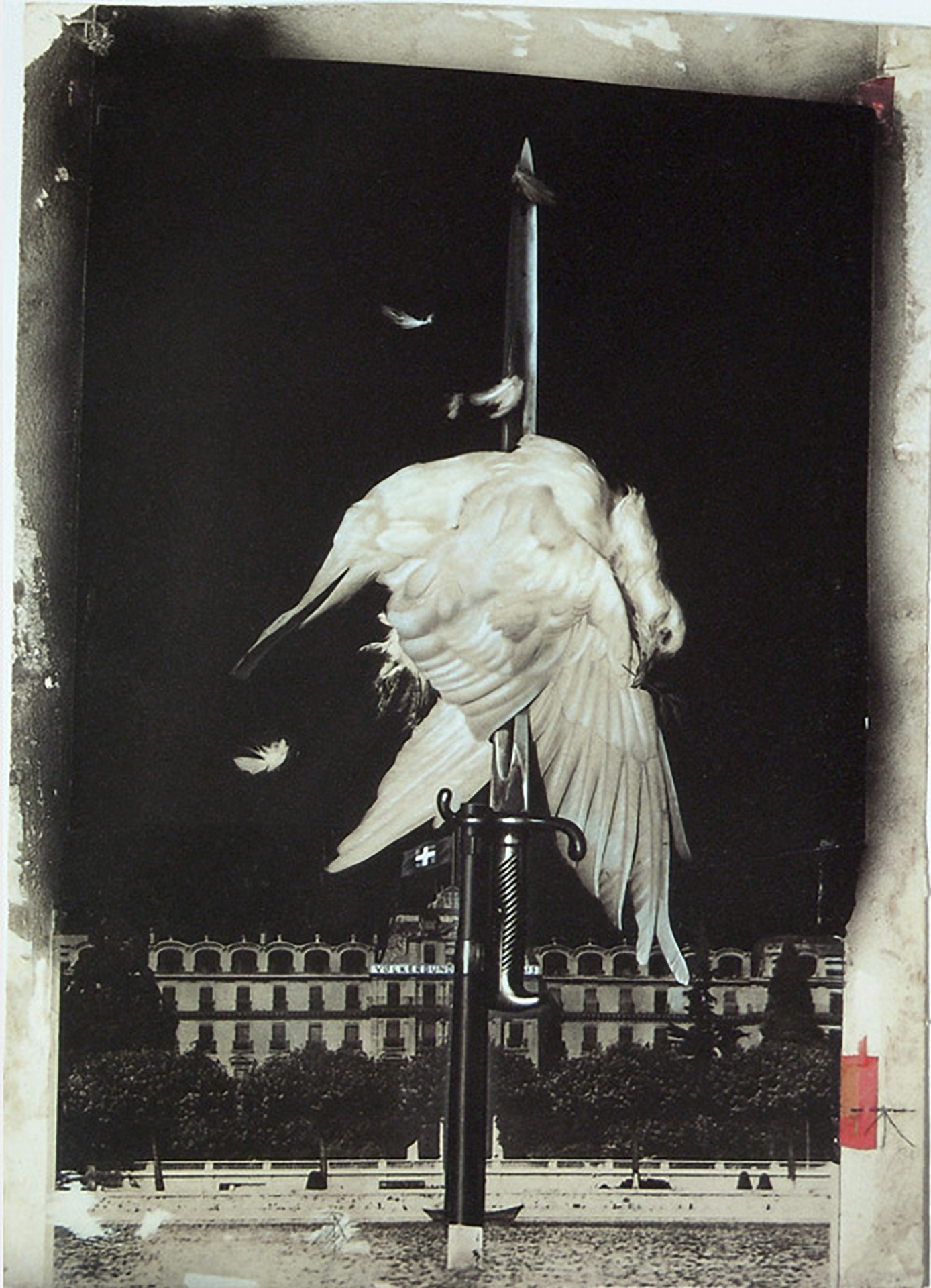

John Heartfield [Helmut Herzfeld], Niemals wieder! [Never Again!], 1932

For the cover of AIZ – Arbeiter-Illustrierte-Zeitung, November 27, 1932

photomontage, exhibition print

© 2019 Heartfield Community of Heirs. All Rights Reserved

https://www.johnheartfield.com/John-Heartfield-Exhibition

Stuart Davis, Artists Against War and Fascism, 1936

gouache on paper, exhibition print

Collection of Louisa and Fayez Sarofim

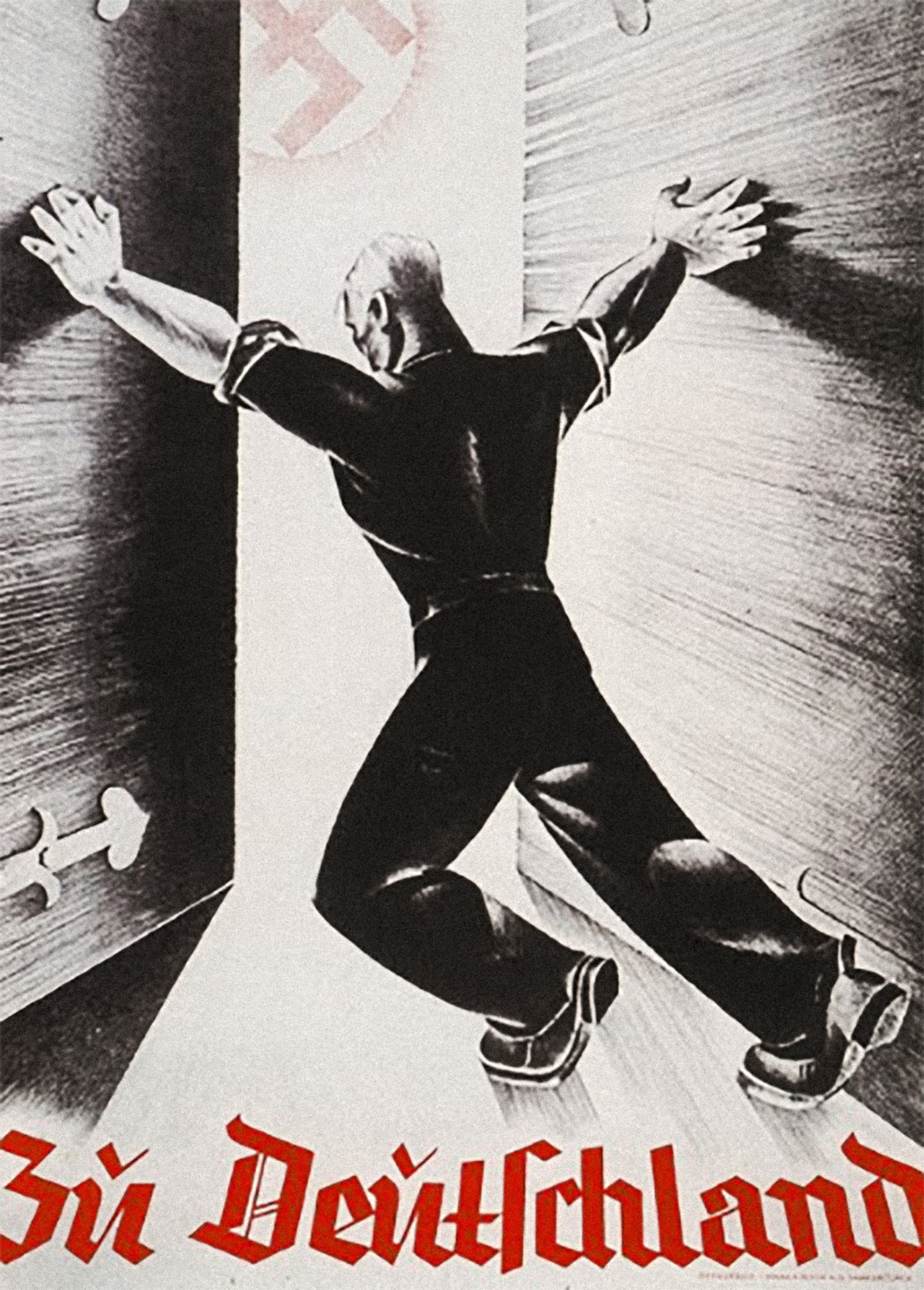

By the time of the birth of the poem “A Breath of Air!”, the re-armament of Germany, which ran counter to the resolutions of the Treaty of Versailles, was of great concern to the countries of Europe. Germany began to challenge the new borders that were defined by the Treaty, yet the first territory, the Saar region, “returned to the homeland” in a peaceful way. During the negotiations of the victorious powers of the First World War in Versailles in 1919, the French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau demanded the complete annexation of the Territory of the Saar Basin—a 2500-square km region on the border—to France as reparation for the war damage caused by the German Reich in France. After long disputes with the other victors of WWI (Great Britain, Italy and the USA) a compromise solution was reached, according to which a newly created Saar area was to be temporarily subordinated to an international government commission . The population of the Saar should only vote on their future fate themselves after a certain (not predefined) period had expired. The Treaty put the Saar under League of Nations control and allowed the French to run its valuable coal mines for the next fifteen years. At the end of that period the people of the Saar would vote to decide their future, whether they would remain under the control of the League of Nations, become part of France, or return to Germany. The plebiscite was finally held in early 1935. While most political groups in the Saar supported a return to Germany before Adolf Hitler’s rise to power, opponents of Nazism in the Saar began having doubts and misgivings afterwards. The Communists and Socialists supported a continuation of the League of Nations administration and a delay in the plebiscite until after the Nazis were no longer in power in Germany. In order to achieve victory, the Nazis resorted to “a mixture of cajolery and brutal pressure”. Finally, 90.8% of those voting favored rejoining Germany. The referendum created a particularly tense moment in international politics, with Western powers sending international protection forces to the region because of the aggressive campaign by Germany. Finally, “the Saar’s return to the Homeland” went peacefully.

“Zu Deutschland” [To Germany], Election poster of the Deutsche Front [German Front] in the Saar campaign, (design by Sepp Semar), 1935

poster, exhibition print

Staatskanzlei Saarland, Saarbrücken

Anti-fascist demonstration in the Saar, during the Saar voting campaign. 60,000 anti-fascists assembled to show people that Hitler meant war, 1934

bw. photo, exhibition print

Staatskanzlei Saarland, Saarbrücken

Arrival of the soldiers of the international protection forces before the referendum on January 13, 1935

bw. photo, exhibition print

Staatskanzlei Saarland, Saarbrücken

On March 7, 1936, a total of 30,000 Wehrmacht soldiers crossed the bridges over the Rhine and thus began the German invasion of the demilitarized Rhineland. They set up garrisons in Aachen, Trier and Saarbrücken. With the occupation of a 50 km wide zone, the German Reich broke both the Versailles Treaty of 1919 and the Locarno Pact of 1925. Adolf Hitler justified the breach of the treaties by referring to the German right to self-determination and to the so-called Franco-Soviet Treaty of Mutual Assistance, which he described as a breach of the Locarno Pact. The occupation was extremely risky: a military reaction by the Western powers would have forced the German troops to withdraw immediately. Fascist Italy, however, had already promised in advance that it would not take part in international actions. France refrained from invading because it did not have the support of Great Britain. Foreign countries contented themselves with harsh verbal criticism and condemnation of Germany before the League of Nations. With reference to Alsace-Lorraine, Hitler claimed on March 7th that he had no territorial claims against France. He offered his western neighbors non-aggression pacts and Germany’s return to the League of Nations, but his weak proposals were not accepted. Once again Hitler succeeded in his policy of exploiting the differences between the Western powers, and a combination of peace-loving rhetoric and aggressive measures. In the German Reich, the occupation of the Rhineland meant an enormous gain in prestige for Hitler and reinforced his assumption that the states of Europe would tolerate his expansion policy.

German forces cross into the Rhineland during the reoccupation, March 1936

bw. photo, exhibition print

© Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin

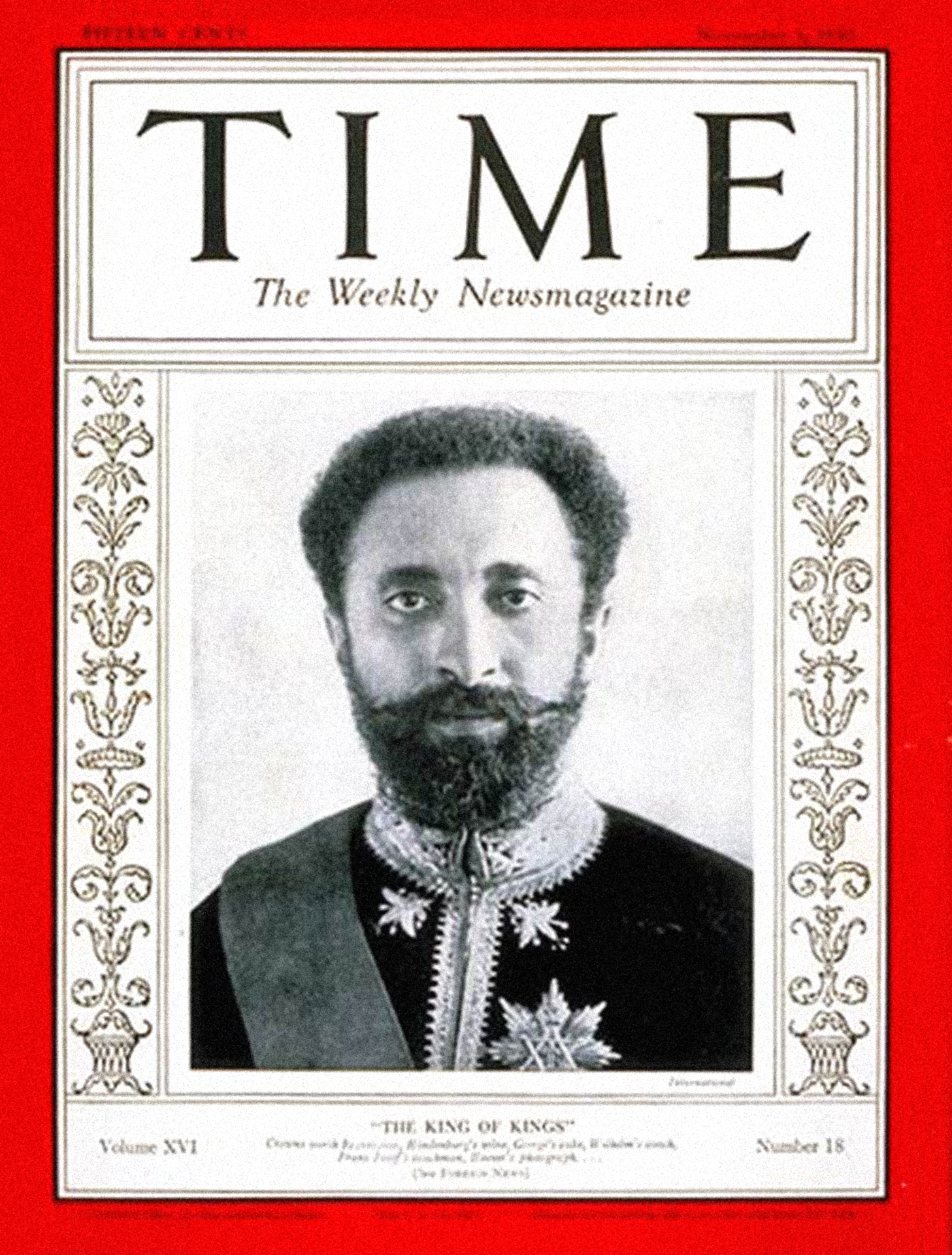

According to a report of the Journal of the Royal African Society on the unfolding conflict between Italy and Abyssinia in October 1935, “It is not often that Africa provides the setting for an international issue of world-wide concern. Such, however, is the Italo-Abyssinian dispute, and one can only hope that it may… find a peaceful solution. Its developments, whatever their nature, must inevitably modify current conceptions both of international relations and responsibilities and of the attitude of Europe towards undeveloped Africa and its people.” The journal’s predictions, however, turned out to be erroneous. The Second Italo-Ethiopian War (also referred to as the Abyssinian War) started in October 1935 and ended in May 1936. The origins of the conflict are diverse and can be traced back to the late 19th century, but the immediate political reasons lie in Benito Mussolini’s interest in renewing the Roman Empire. Ethiopia, the only uncolonized country in Africa and surrounded by Italian colonies (Eritrea and Somalia), was the obvious target for the expansionist policies of the Fascist state. Ethiopia was also the only country that had been able to obtain a lasting victory over a colonial power during the scramble for Africa. The Ethiopian victory at Adwa (1896), which ended the First Italo-Ethiopian War was a thorn in Italy’s imperial pride. The 1935–36 war was short but very costly in human lives, especially on the Ethiopian side. Emperor Haile Selassie was forced to escape into exile, Italy announced the annexation of the territory of Ethiopia on 7 May, and Italian King Victor Emmanuel III was proclaimed emperor. Yet, the country was far from vanquished: two thirds of it were still under Ethiopian control and there had not been any formal surrender. Armed conflicts resumed throughout the years leading up to the Second World War, where Africa, once again, suffered from the wars of the European powers.

Mussolini inspecting troops during the Second Italo-Ethiopian War, 1935

bw. photo, exhibition print

Istituto LUCE, Rome

Abyssinian soldiers, 1936

bw. photo, exhibition print

Åhlen & Åkerlund via IMS Vintage Photos

Cover of Time Magazine: Haile Selassie, the Emperor of Ethiopia, November 3, 1930

exhibition print

© INTERNATIONAL / Time Inc.

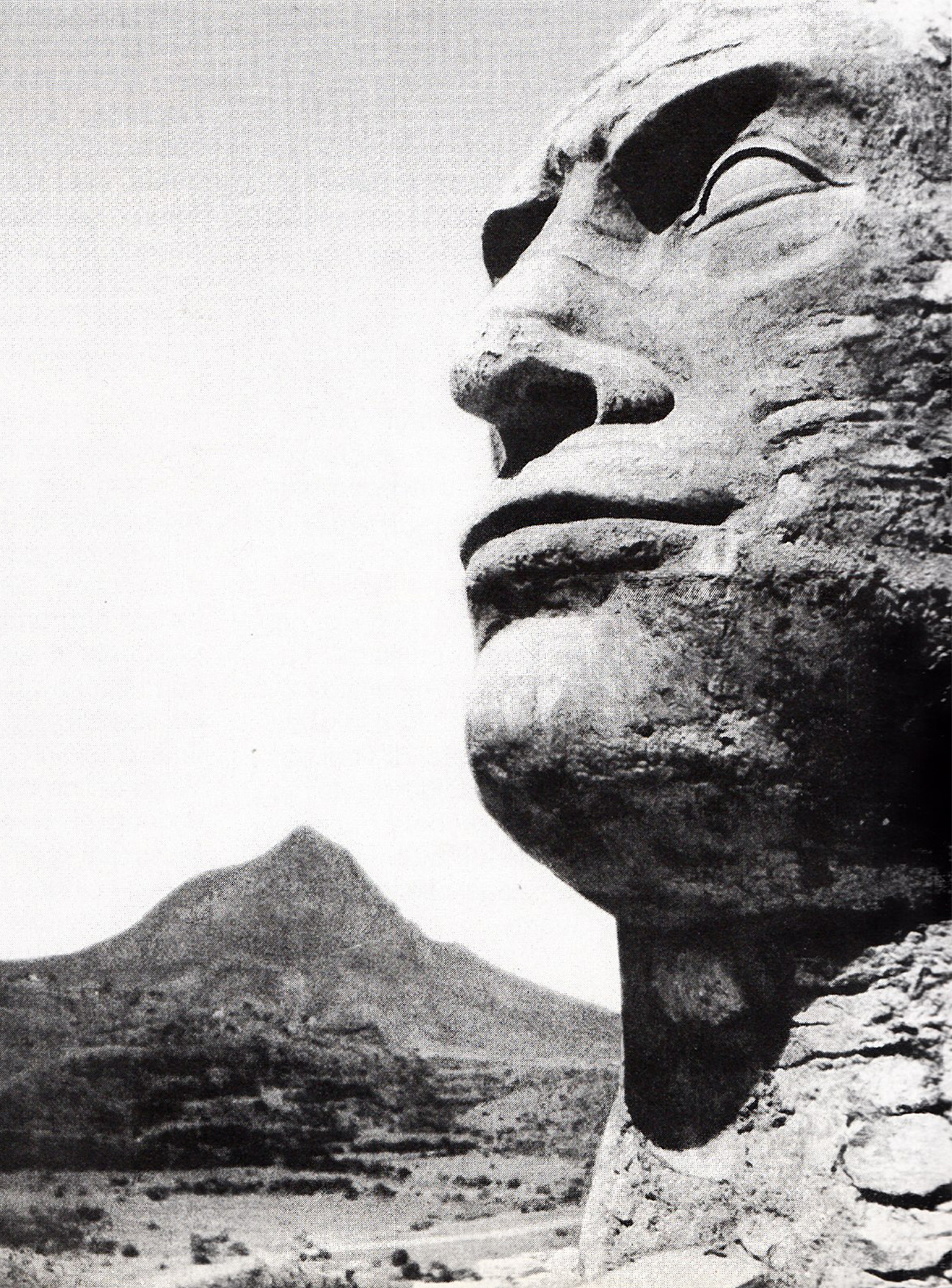

Colossal head of Mussolini built by Italian troops in Ethiopia, 1936

as shown in a LUCE newsreel

bw. photo, exhibition print

Istituto LUCE, Rome

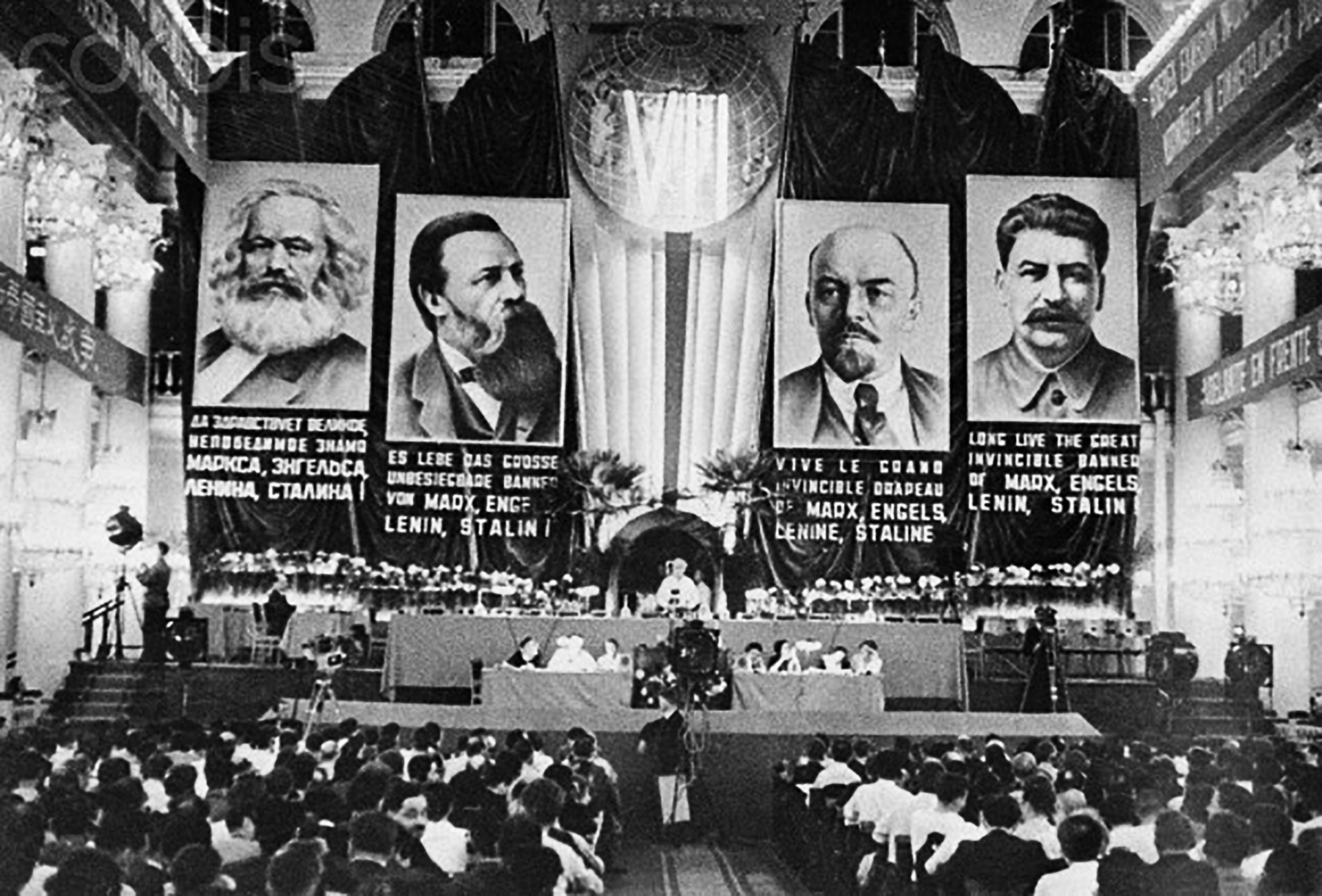

The growing tensions in European politics, as well as the threat of the rapid spread of Fascist and Nazi ideas in almost all countries of Europe warned many intellectuals that the fight between left-wing parties was futile and dangerous. Attila József was among these intellectuals who pleaded the importance of a united front. However, he was heavily criticized because of the political essay Az egységfront körül [On the United Front, 1933] by the narrow-minded Muscovite party leaders of the Hungarian Communist Party (KMP), which was a consequence of his leaving the Party. Two years later, the official politics of the Communist International changed—they no longer saw an enemy in the Social Democrats, whom they previously considered “social fascists.” This U-turn in Comintern policy was announced during the 7th World Congress of the Communist International (Comintern), which was held between July 25 and August 20, 1935 in Moscow. At the Congress, representatives of Communist parties from around the world met representatives of various political and labor organizations. Held seven years after the last Comintern World Congress (in 1928), the Congress in 1935 significantly altered the agenda of its previous meeting. Instead of orienting towards class warfare, concerned with the unprecedented danger of spreading of Fascism in Europe, the 7th Congress focused on the need to advocate for collective security between the Soviet Union and European capitalist states. The 7th Congress was marked by two keynote reports. The first was delivered on the second day of the gathering by Wilhelm Pieck of the Communist Party of Germany (KPD), who warned about certain advantages that the Fascists had over the Communists, including in mobilizing the masses. The second keynote, delivered by Georgi Dimitrov, Bulgarian Communist politician, chosen by Joseph Stalin in 1934 to be the head of the Comintern. Dimitrov, whose position among the Communist leadership was secured after his victory at the Leipzig trial, was eventually elected General Secretary of the Comintern during the 7th Congress. In his keynote speech, Dimitrov emphasized the need for the working class to unite forces to efficiently oppose Fascism. Dimitrov’s proposition was generally accepted by the delegates, and the new “Popular Front” policy resulted in successful political alliances of left-wing parties in the French and Spanish elections of 1936. The idea of the “Popular Front” also emerged in various cultural initiatives and events, including the First International Congress of Writers for the Defense of Culture in Paris in 1935.

The 7th World Congress of the Communist International (Comintern) in the Halls of Pillars of the House of Unions in Moscow, 1935

bw. photo, exhibition print

RIA Novosti

The 7th World Congress of the Communist International (Comintern): John Ross Campbell, Joseph Stalin and Georgi Dimitrov, the latter was appointed General Secretary at the 1935 Congress, 1935

bw. photo, exhibition print

SPUTNIK / Alamy

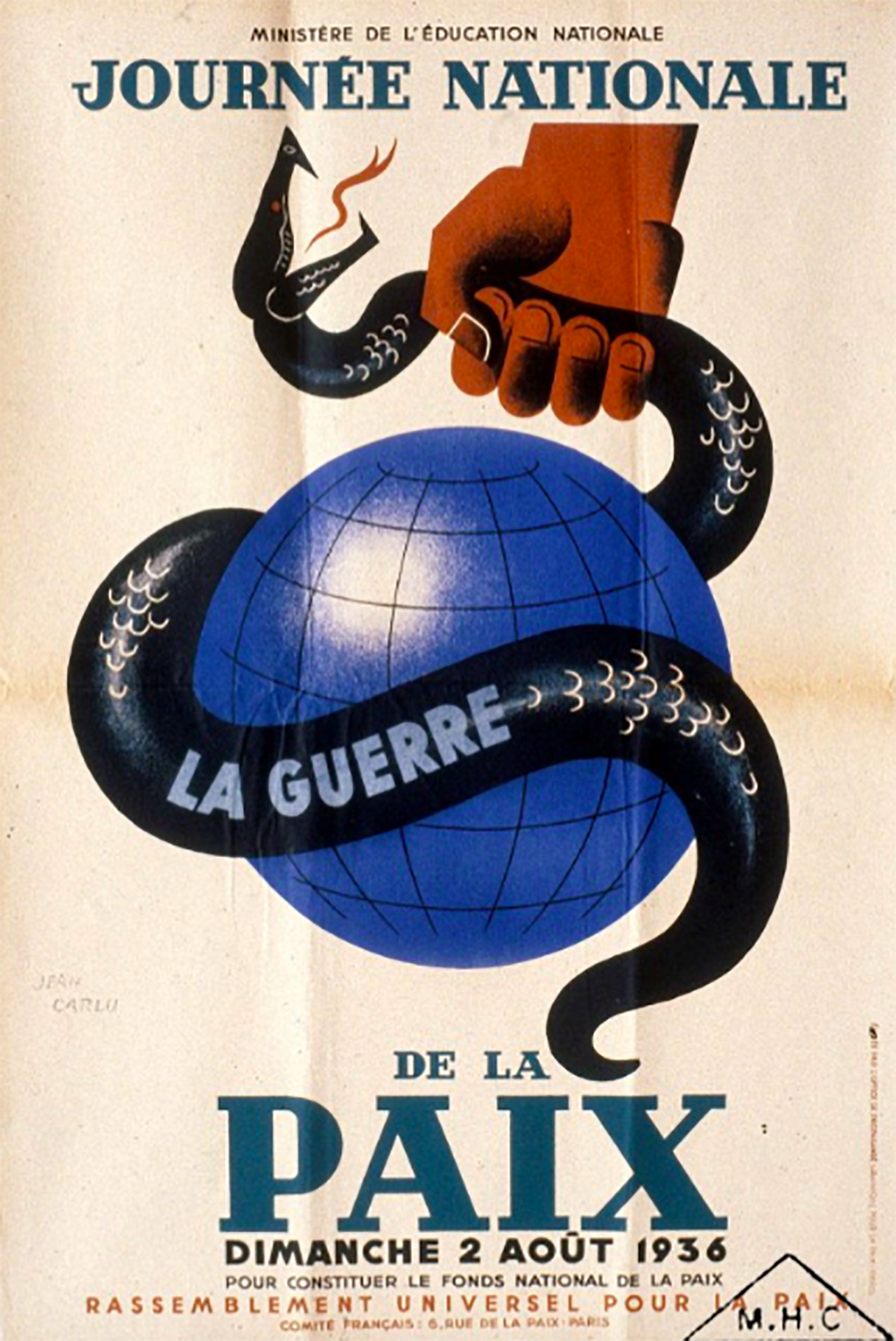

The fight against Fascism was backed by the new Comintern policies, and it found supporters also outside of the political left. One of the major issues that occupied—sometimes literally—the public space was the possibility of a new war. The immense loss of life during the First World War, for what became regarded as futile reasons, caused a sea-change in public attitudes to militarism. In the aftermath of WWI many organizations formed, including the War Resisters’ International, the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom, the No More War Movement and the Peace Pledge Union, that led international anti-war campaigns. The League of Nations also convened several disarmament conferences in the inter-war period such as the Geneva Conference in 1927. By the mid-1930s, the war seemed closer than ever. Massive anti-war demonstrations and campaigns protested the accelerating armament, often backed up by left-wing or Popular Front governments, as was the case in France.

David Seymour “Chim” [Dawid Szymin], Anti-war rally, St Cloud, Paris, 1936

bw. photo, exhibition print

© David Seymour / Magnum Photos

Poster of the Journée nationale de la Paix [National Peace Day], 1936

design by Jean Carlu

poster, exhibition print

© Adagp, Cirip – Photo Alain Gesgon

In the spring of 1935 a group of French intellectuals organized the International Writers’ Congress for the Defense of Culture [Congrès international des écrivains pour la défense de la culture], perhaps the largest and most ambitious mobilization of its kind. Held in June at the Palais de la Mutualité, the congress was intended to rally the European intelligentsia in the fight against Fascism. More than 250 participants from 38 countries attended the discussions that took place between 21 and 25 June every afternoon and evening. Among the participants were esteemed literary and artistic figures of the decade: André Malraux, André Gide, Tristan Tzara, Aldous Huxley, Edward Morgan Forster, Boris Pasternak, and Isaac Babel. The congress, initiated and organized by Romain Rolland and Henri Barbusse, became an attempt by the literary world to respond to the slogan of the “Popular Front”. The event was held under the patronage of Maxim Gorky; and the contributions of many well-known German and Austrian émigrés, among these, Anna Seghers, Heinrich and Klaus Mann, Robert Musil, Bertolt Brecht and Lion Feuchtwanger, had a considerable impact on the Congress. The agenda dealt with subjects like “cultural heritage”, “nation and culture” and “the role of the author in society”. Many of the French participants—including Malraux, Gide, playwright Jean-Richard Bloch and Louis Aragon—were Communists or philo-Communists. The Soviet delegates—Boris Pasternak, Ilya Ehrenburg and others—also supported the Stalinist agenda. Aldous Huxley was indignant and complained of five days of “endless communist demagogy”. On his return to England, he wrote that he had hoped for “serious, technical discussions... but, in fact, the thing simply turned out to be a series of public meetings organized by the French Communist writers for their own glorification and the Russians as a piece of Soviet propaganda”. But some writers managed to protest against the imprisonment of opponents of Stalin. Magdeleine Paz courageously delivered a long plea for the liberation of Victor Serge, a dissident Belgian-born Muscovite official of the Third International deported to the Urals. Postponed from an evening plenary session, her speech did not conform to the organizers’ purpose of condemning only Nazi abuses and praising Soviet antifascism. The Paris congress proved to be a failure. No binding decisions were made on the common position of the progressive creative community as the positions of those who attended it were far too diverse—a dispute between the surrealist André Breton and the Soviet delegate Ilya Ehrenburg was particularly symbolic. Yet it was the first congress in history where the notion of cultural freedom and the danger of totalitarianism were so widely debated. After the congress, Brecht summed it up in words of acid irony: “We have just saved culture. It took a total of four days, during which we decided that it’s better to sacrifice everything than to let culture be destroyed. If necessary we are ready to sacrifice 10 or 20 million people to this end.” Nevertheless, it was seen by many as a success as it had given space to a voice of protest, those who attended gave each moral support and networks were established. In the three years following, further congresses of different formats were held in Lviv, Valencia and in London. During the Paris Congress, the organization “International Association of Writers for the Defense of Culture” was formed, to which—according to the reports of Hungarian newspapers—writers from all states applied with the exception of Germany, Italy, Romania and Hungary.

Gisèle Freund, Henri Barbusse, Alexey Tolstoy and Boris Pasternak at the First International Congress of Writers for the Defense of Culture at the Palais de Mutualité, Paris, France, 1935

bw. photo, exhibition print

© Gisèle Freund

David Seymour “Chim” [Dawid Szymin], First International Congress of Writers for the Defense of Culture at the Palais de Mutualité, Paris, France, 1935

(from the left) Paul Vaillant-Couturier, André Gide, Jean Richard Bloch, speaking: André Malraux.

bw. photo, exhibition print

© David Seymour / Magnum Photos

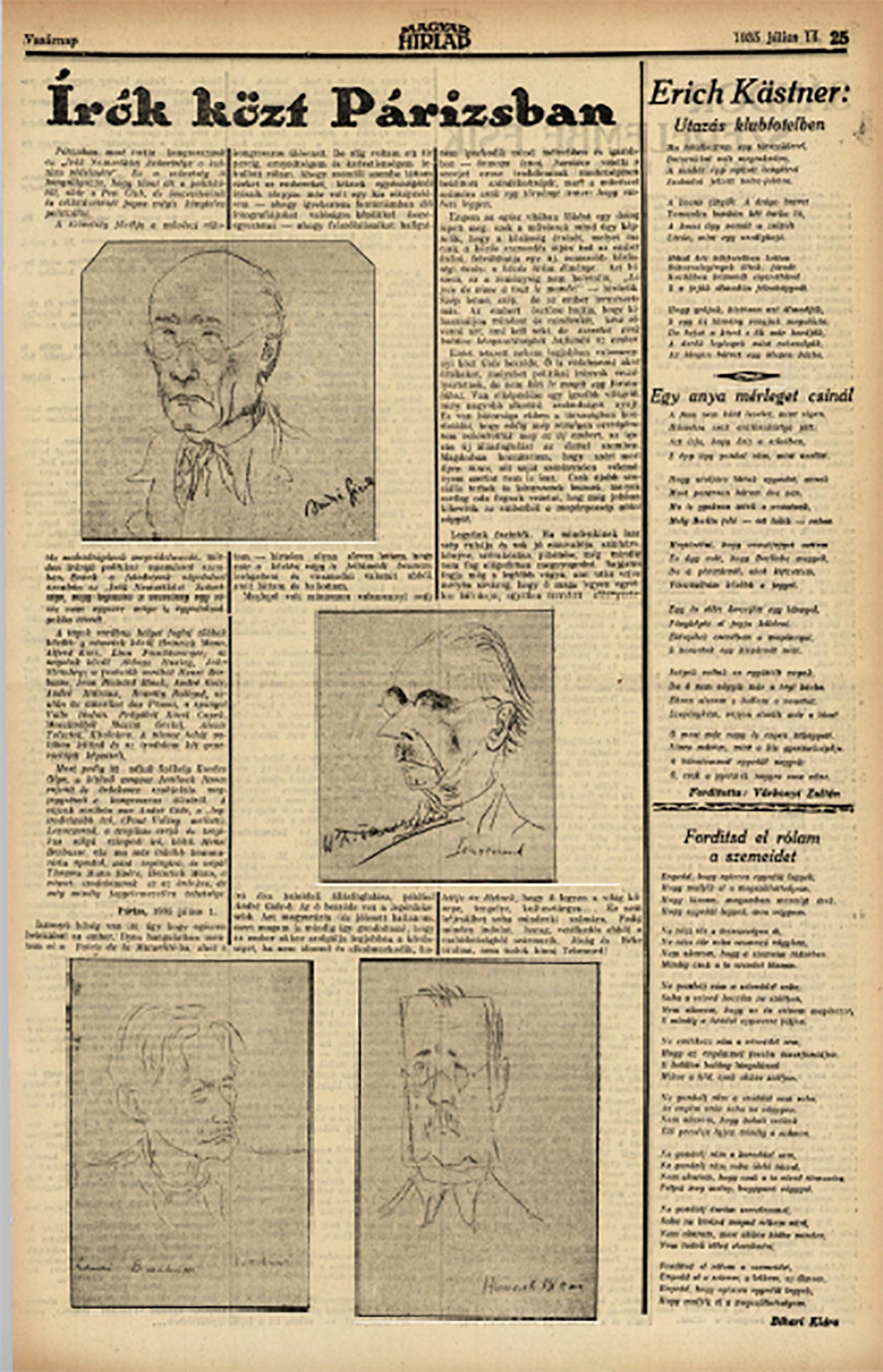

“Among writers in Paris” – report in the Magyar Hírlap on the First International Congress of Writers for the Defense of Culture, 1935

exhibition print,

Magyar Hírlap, July 14, 1935 / Arcanum

Gisèle Freund, Anna Seghers and Gustav Regler at the First International Congress of Writers for the Defense of Culture at the Palais de Mutualité, Paris, France, 1935

bw. photo, exhibition print

© Gisèle Freund

Bertolt Brecht left Berlin one day after the Reichstag fire in February 1933, and fled abroad, going from one city to the next (Prague, Vienna, Zurich, and Paris), finally settling down in Demark in 1933. By this time, he was one of the most well-known German playwrights, his Dreigroschenoper [The Threepenny Opera, 1928], with Kurt Weill’s emblematic music, had been translated into 18 languages and performed more than 10,000 times on European stages. His poems (like the volume Hauspostille [Devotions for the Home], 1927) were also highly appreciated by the literary public all over Europe; Brecht’s “songs” also influenced the poetry of Attila József in the first half of the 1930s. Brecht’s plays in the 1930s, written in exile, illustrated the views and theorems of left-wing ideology with a consciously applied and voiced intent, and sought a direct enlightening and educational effect. As an ardent anti-fascist and defender of the freedom of culture, he was very vocal in his theoretical writings as well, as in the political-literary essay Fünf Schwierigkeiten beim Schreiben der Wahrheit [Writing the Truth: Five Difficulties, 1934], where he stated that a writer needs “the courage to write the truth when truth is everywhere opposed; the keenness to recognize it, although it is everywhere concealed; the skill to manipulate it as a weapon; the judgment to select those in whose hands it will be effective; and the cunning to spread the truth among such persons.” In 1941 Brecht fled the war and went to the United States. In the years of the Cold War and “Red Scare”, he was blacklisted by movie studio bosses and interrogated by the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1947. Unlike many of the accused, including the “Hollywood Ten”, Brecht decided to testify, where he stated he had never been a Communist Party-member. Brecht’s decision to appear before the committee led to criticism, including accusations of betrayal. The day after his testimony, Brecht returned to Europe. First he lived in Zurich, but then he moved to East-Berlin where he established the theatre company the Berliner Ensemble. Brecht’s involvement in agitprop and lack of clear condemnation of the purges resulted in criticism from many contemporaries who became disillusioned in Communism earlier. Today, his poems and plays belong to the most important literary achievements of the 20th century, and, because of his ardent fight for the freedom of culture, many scholars have stressed the significance of Brecht’s original contributions in political and social philosophy.

David Seymour “Chim” [Dawid Szymin], German poet and playwright Bertolt Brecht having his portrait drawn at the First International Congress of Writers for the Defense of Culture at the Palais de Mutualité, Paris, France, 1935

bw. photo, exhibition print

© David Seymour / Magnum Photos

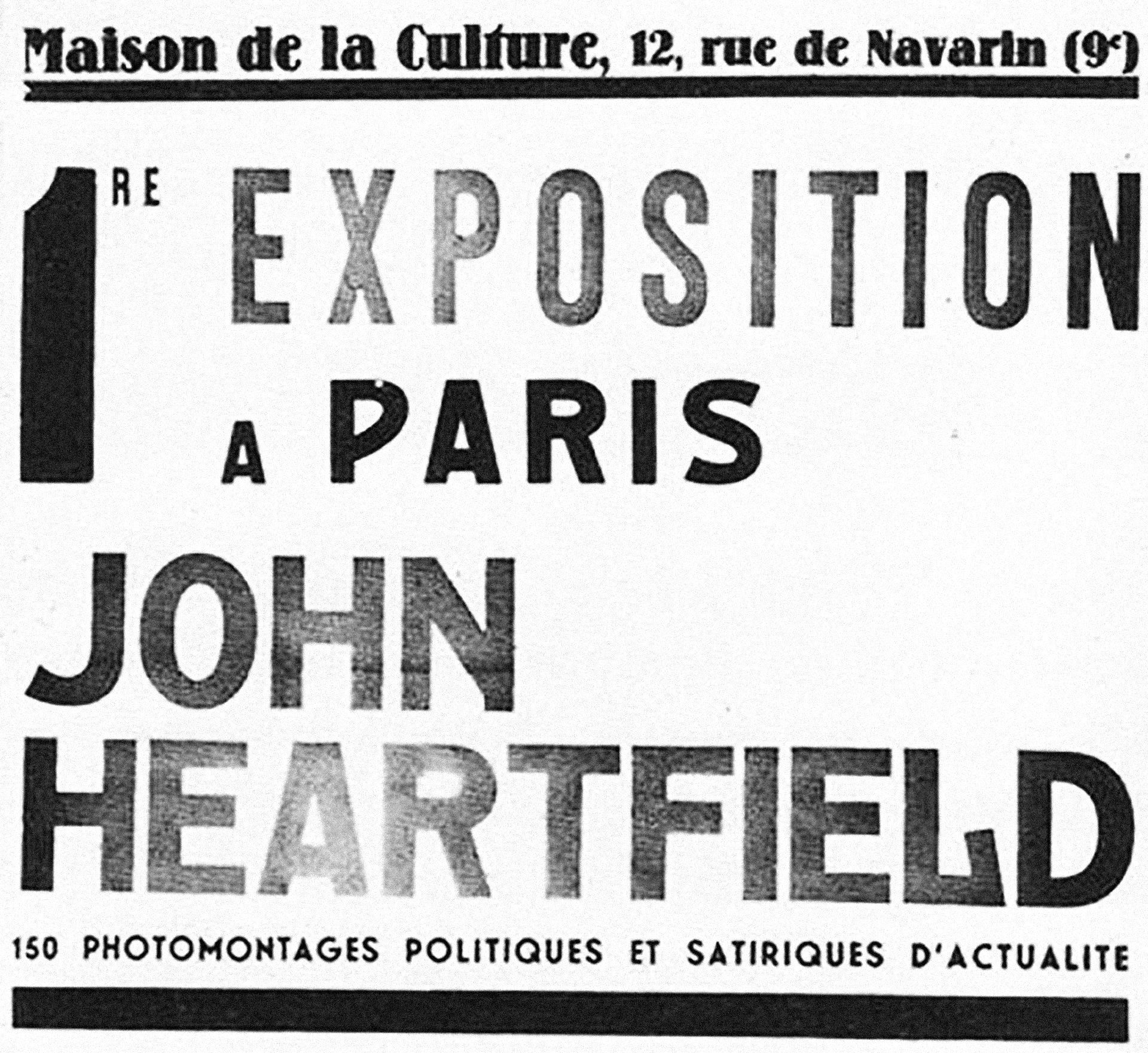

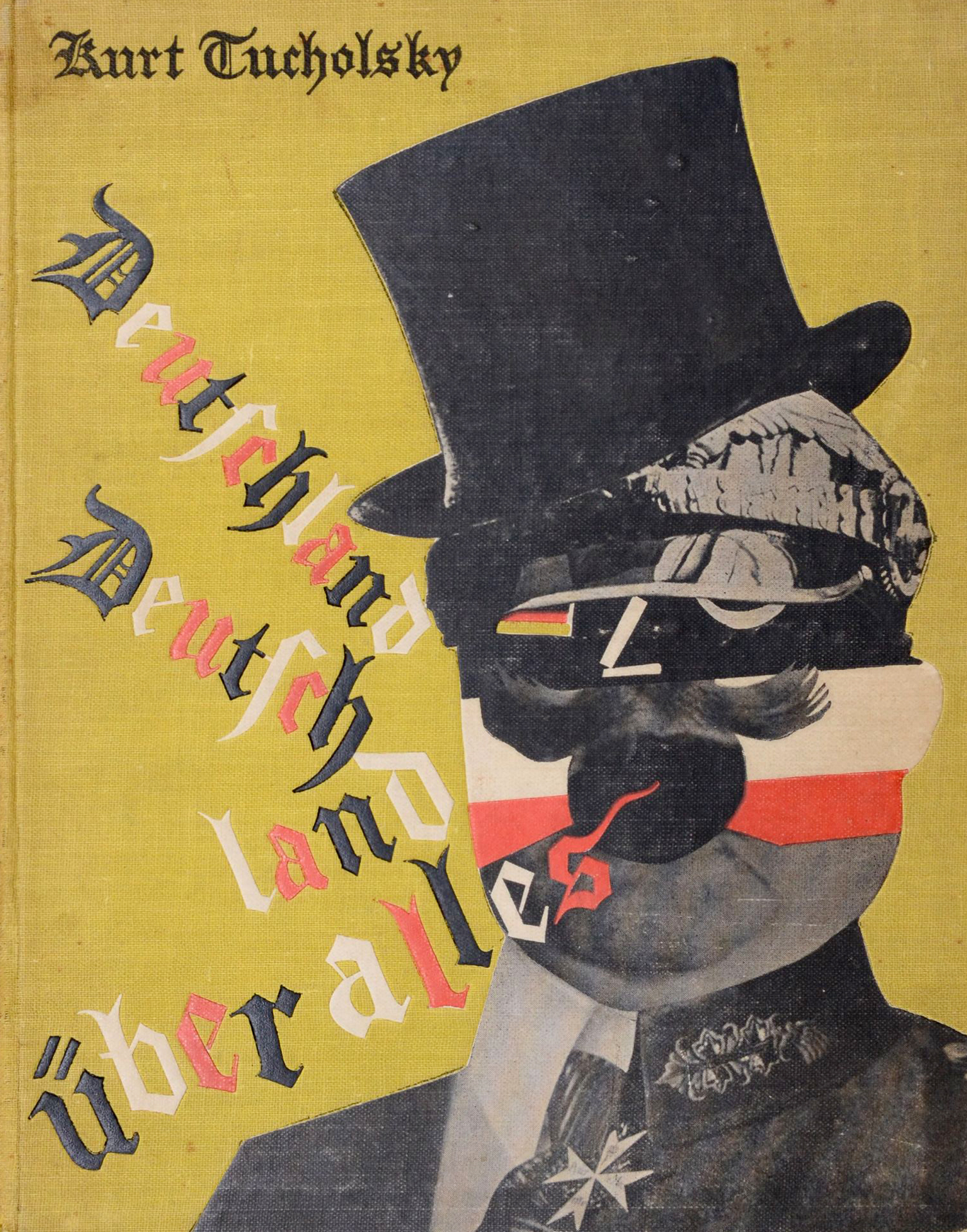

In 1935, John Heartfield, co-founder of the Berlin Club Dada and famous contributor to the communist weekly Arbeiter-Illustrierte-Zeitung (commonly abbreviated as AIZ), was invited to Paris by the Association des écrivains et artistes révolutionnaires [Association of Writers and Revolutionary Artists], then directed by Louis Aragon, to present the first French exhibition of his works at the Maison de la Culture. The exhibition, heralded by the subtitle “150 current political and satirical photomontages”, took place in the context of the vast debate, which animated the French artistic and cultural scene around the issues of realism. On the occasion of the exhibition, Louis Aragon published the essay John Heartfield et la Beauté Revolutionnaire [John Heartfield and the Revolutionary Beauty, 1935] in the Commune, the journal of the association. In this text Aragon described Heartfield as a follower of artists such as Francisco de Goya and Honoré Daumier, who always pointed to the most burning issues of their time with their satirical and acerbic works. Indeed, Heartfield’s montages merged avant-garde formal experimentation with trenchant political satire. As one researcher pointed out, Heartfield’s work “has also often been understood as straightforward ‘popular front’ propaganda and the accomplished embodiment of the ‘dialectical’ method that were significant aspects of the cultural policy of the official left.” By no coincidence—Heartfield signed up with the KPD (Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands, Communist Party of Germany], allegedly at its first congress in 1918, receiving his party membership card from Rosa Luxemburg herself. Yet, Heartfield’s works were addressing issues—the Nazi threat, socials inequalities, the impending war—and attracted a broad audience from all over the political Left. He depicted the society of the Weimar Republic with biting sarcasm in the book published with Kurt Tucholsky, Deutschland, Deutschland über alles [Germany, Germany above all], and in the montages he created for the Arbeiter-Illustrierte-Zeitung (AIZ). After the Nazi takeover, the AIZ had to relocate to Prague, and Heartfield also fled the Nazis to Czechoslovakia after the SA stormed his home. From Prague he continued his work for the AIZ, in which his political photo montages appeared regularly until 1938. After the occupation of the Sudetenland, Heartfield fled to Great Britain where he took part in events organized by the Freier Deutscher Kulturbund in Großbritannien [Free German League of Culture in Great Britain] and worked as a book designer for English publishers. After WWII he followed his brother, Wieland Herzfelde to the German Democratic Republic.

Poster of John Heartfield’s exhibition at the Maison de la Culture, Paris, 1935

poster, exhibition print

[Laurent Baridon, Frédérique Desbuissons and Dominic Hardy, ed, L’Image railleuse (The mocking image), Paris: INHA, 2019, 287]

Kurt Tucholsky, Deutschland, Deutschland über alles. Montiert von John Heartfield [Germany, Germany above all. Assembled by John Heartfield], 1929

Berlin: Neuer Deutscher Verlag, 1929

Foldvaribooks, Budapest

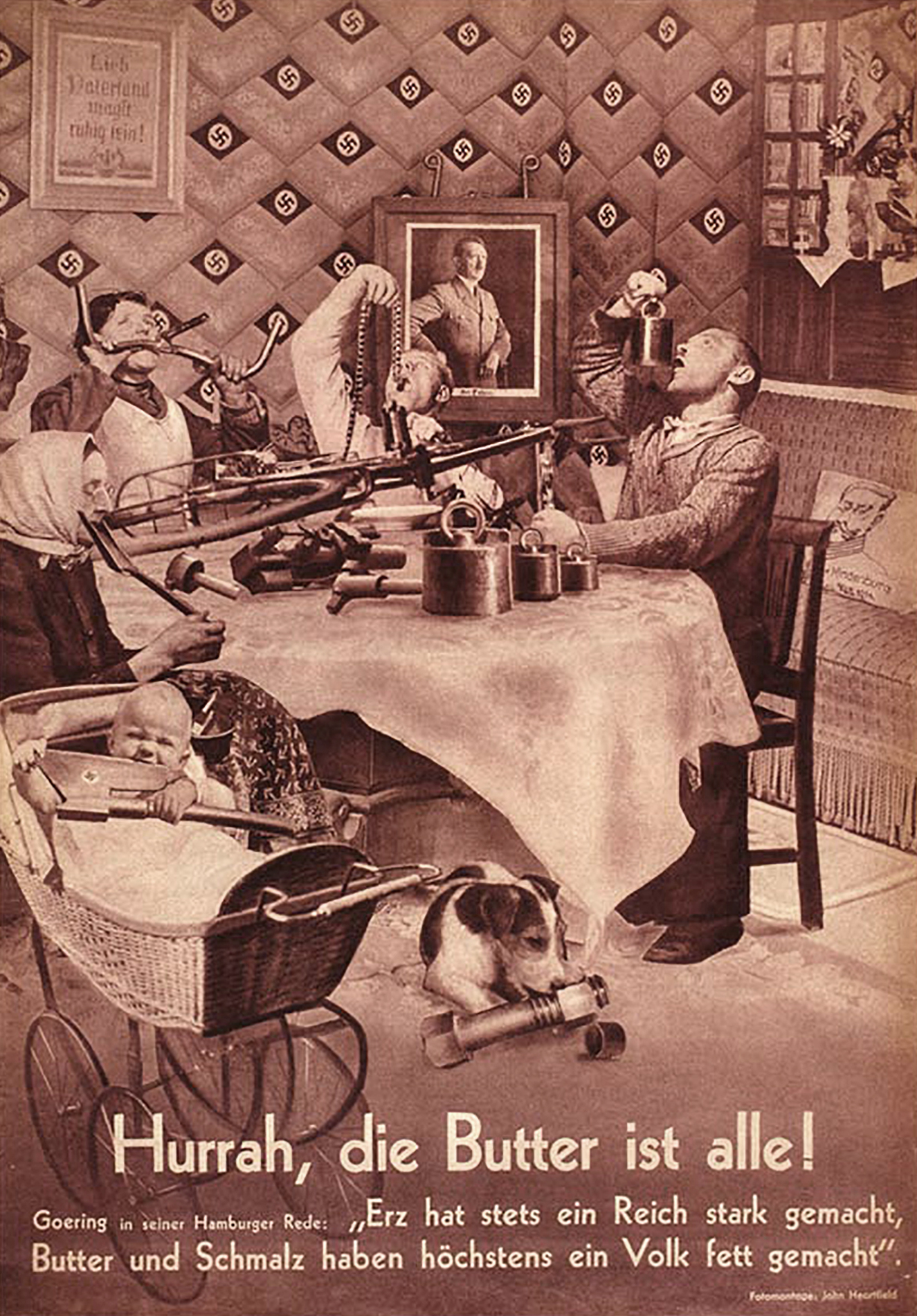

John Heartfield [Helmut Herzfeld], Hurrah, die Butter ist alle! [Hurrah, There’s No Butter Left!], 1935

“Goering in seiner Hamburger Rede: ‘Erz hat stets ein Reich stark gemacht, Butter und Schmalz haben höchstens ein Volk fett gemacht’.” [Göring in his Hamburg speech: “Ore has always made an empire strong, butter and lard have made a people fat at most.”]

Cover of AIZ – Arbeiter-Illustrierte-Zeitung (Prague), December 19, 1935

photomontage, exhibition print

© 2019 Heartfield Community of Heirs. All Rights Reserved

https://www.johnheartfield.com/John-Heartfield-Exhibition

George Grosz, member of the Berlin Dada movement, and friend of John Heartfield and his brother Wieland Herzfelde, was an ardent supporter of pacifism. In his autobiography, Ein kleines Ja und ein großes Nein [George Grosz: An Autobiography] he wrote about his experiences of the First World War: “What can I say about the First World War, a war in which I served as an infantryman, a war I hated at the start and to which I never warmed as it proceeded? I had grown up in a humanist atmosphere, and war to me was never anything but horror, mutilation and senseless destruction….” By the war’s end in 1918, Grosz had developed an unmistakable graphic style of ferocious social caricature. Based on his wartime experiences and his observations of the chaotic post-war period, he created a series of works savagely attacking militarism, war profiteering, and social inequalities. In his drawing series such as Das Gesicht der herrschenden Klasse [The Face of the Ruling Class, 1921] and Ecce Homo (1922), Grosz depicted the Junkers, greedy capitalists, smug bourgeoisie, drinkers, and lechers—as well as hollow-faced factory laborers, the poor, and the unemployed. Gradually, Grosz became associated with the Neue Sachlichkeit (“New Objectivity”) movement, which embraced realism as a tool of satirical social criticism. Along with Heartfield, Grosz clearly saw the danger of Nazism and social decadence. So famous and threatening were Grosz’s depictions of war and corruption that the Nazis designated him “Cultural Bolshevist Number One.” Bitterly anti-Nazi, Grosz left Germany shortly before Hitler came to power. In his absence, his work was included in the infamous 1937 Entartete Kunst [Degenerate Art] exhibition that opened in Munich before touring throughout Germany. After emigrating to the USA in 1933, Grosz gradually moved away from his previous work, and caricature in general. In place of his earlier corrosive vision of the city, he now painted conventional nudes and many landscape watercolors. Works, such as Kain, oder Hitler in der Hölle [Cain, or Hitler in Hell, 1944], were the exception. In his autobiography, he wrote: “A great deal that had become frozen within me in Germany melted here in America and I rediscovered my old yearning for painting. I carefully and deliberately destroyed a part of my past.” Although a softening in his style had been apparent since the late 1920s, Grosz’s work assumed a more sentimental tone in America, a change generally seen as a decline.

George Grosz, Der Botschafter des guten Willens [The Ambassador of Good Will], 1936

watercolor, ink, exhibition print

New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art © George Grosz Estate

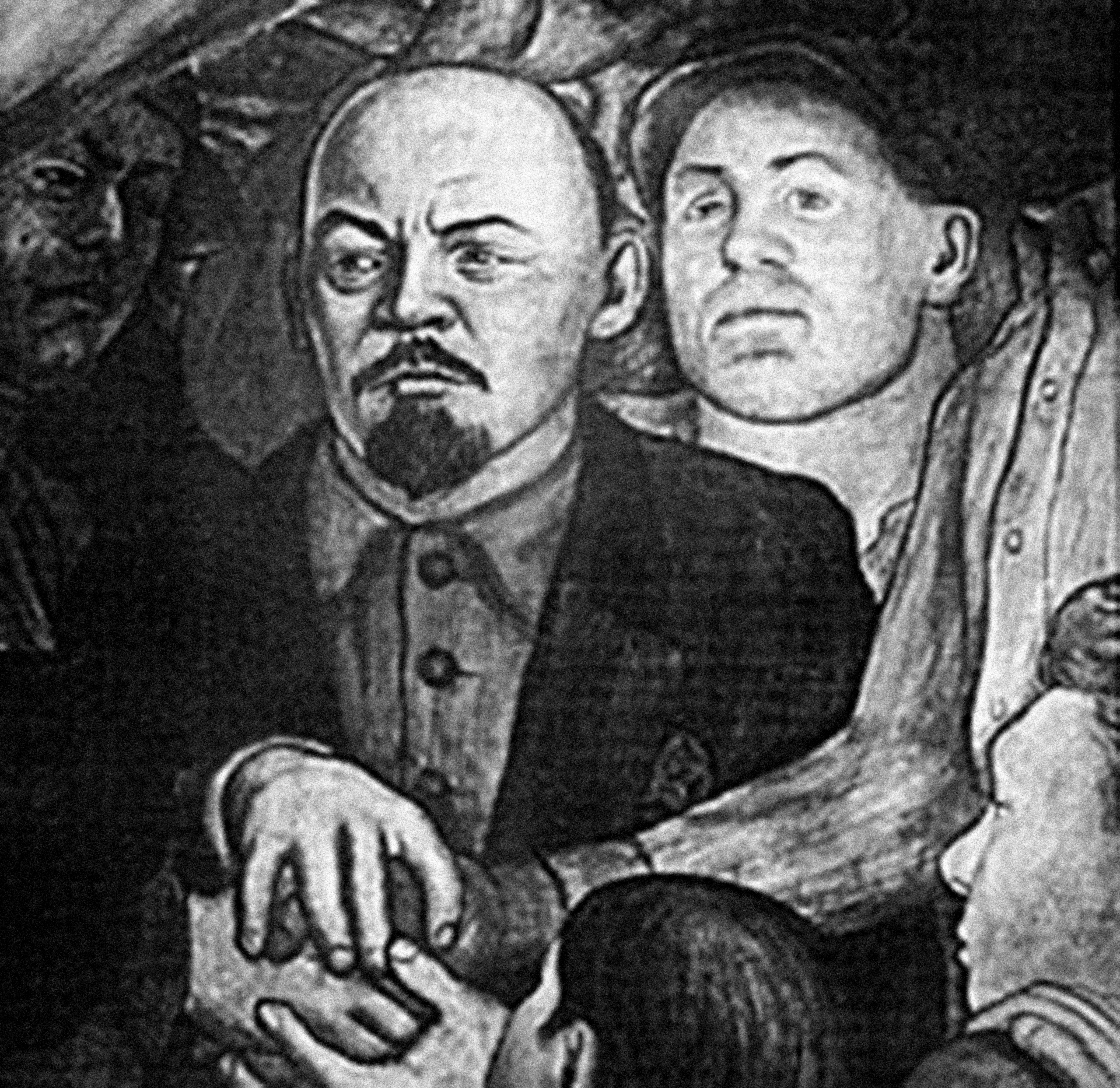

The United States—though it was far from the tensions of European politics—was not free from ideological artistic debates, either. One of the major controversies of the 1930s in the American art scene was the removal of Diego Rivera’s mural, Man at the Crossroads from the Rockefeller Center in 1934. By the 1930s, Mexican muralist Diego Rivera had gained international reputation with his lush and passionate murals. As a left-wing (Trotskyite) artist, in the United States he found himself at the center of a circle of left-wing painters and poets. His talent also attracted wealthy patrons, including Abby Aldrich Rockefeller. In 1932, she convinced her husband, John D. Rockefeller, Jr., to commission a Rivera mural for the lobby of the soon-to-be-completed Rockefeller Center in New York City. Rivera proposed a 63-foot-long portrait of workers facing symbolic crossroads of industry, science, socialism, and capitalism. The controversy began when the New York World-Telegram complained about the piece, which was still in progress, calling it “anti-capitalist propaganda.” Rivera, defiantly, added an image of Vladimir Lenin and a Soviet Russian May Day parade to the mural in protest. Horrified by the scandal, Nelson Rockefeller—at the time a director of the Rockefeller Center—decided to hide the mural behind a massive drape. Rivera was paid his full fee, and despite demonstrations by fellow-artists, and despite negotiations to transfer the work to the Museum of Modern Art, the mural was demolished. It was replaced by a mural from Josep Maria Sert three years later. Only black-and-white photographs exist of the original incomplete mural, which were used by Rivera when he later recreated the frescoes in the Palacio de Bellas Artes [Palace of Fine Arts] in Mexico City, under the alternative title Man, Controller of the Universe. The Rockefeller–Rivera dispute has become an emblem of the relationship of politics, aesthetics, creative freedom and economic power.

Diego Rivera stands with a copy of the mural Man at the Crossroads, 1934

bw. photo, exhibition print

© Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico City

Diego Rivera. Detail of the mural A Man at the Crossroads, portrait of Lenin, 1934

bw. photo, exhibition print

© Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico City

Diego Rivera, Man, Controller of the Universe, 1934

mural on the Palacio de Bellas Artes, Mexico City, photo reproduction

wikimedia commons

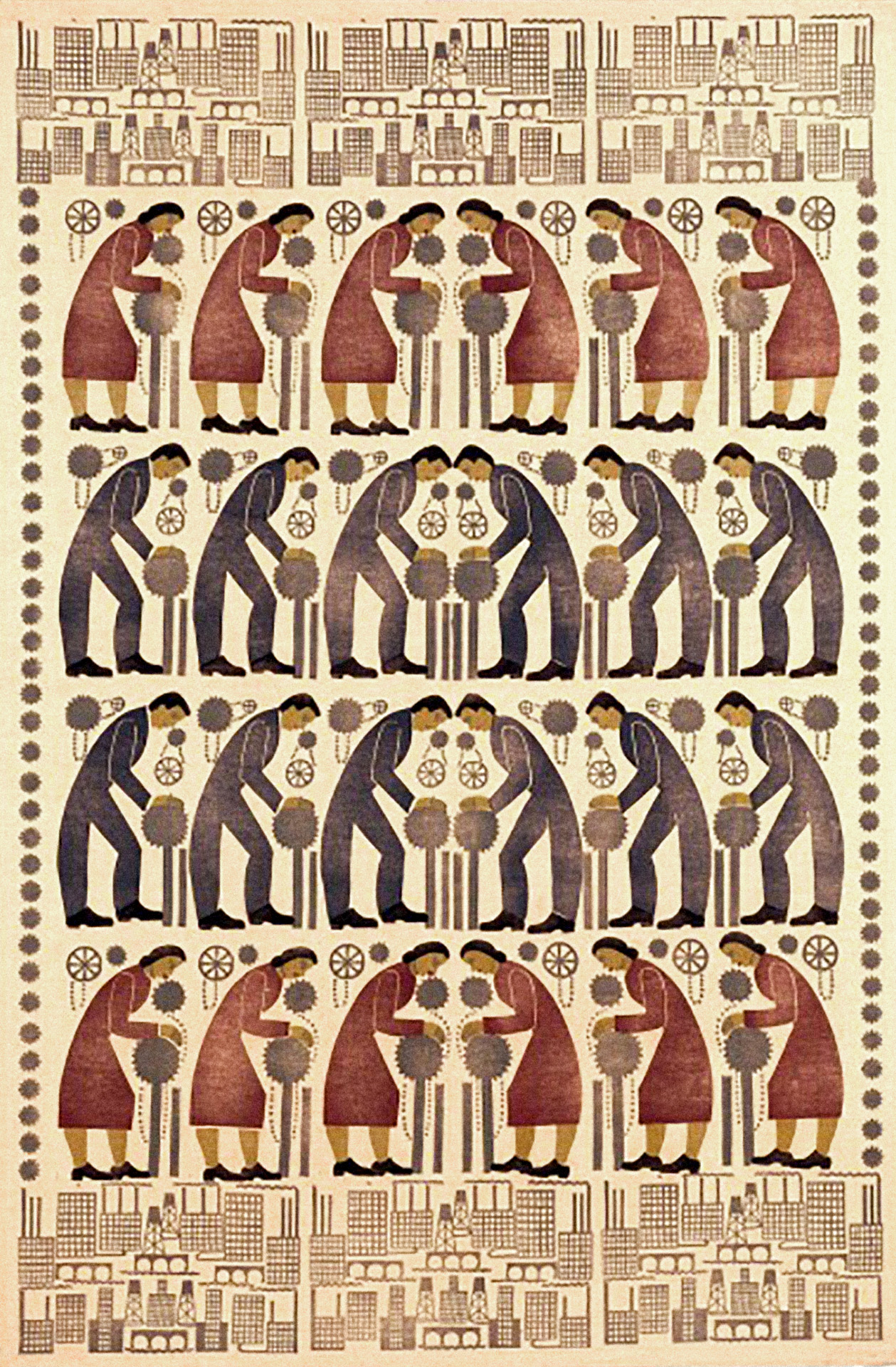

While artists in Europe had to endure many hardships because of the threatening European political climate and the Great Depression, the United Stated Government set up several programs, as part of the New Deal Program, to support artists in these hard times. The Federal Art Project (FAP) was created in 1935 to provide work relief for artists in various media—painters, sculptors, muralists and graphic artists, with various levels of experience; it was supported by the Works Progress Administration (WPA). Holger Cahill, a curator and fine and folk art expert, was appointed director of the FPA. Cahill and his staff could rely on the experience gained from a similar project, the Public Works of Art Project of 1933–34. As with other Federal cultural projects of the time, the program sought to bring art and artists into the everyday life of communities throughout the United States, through community art centers, exhibitions and classes. The Federal Art Project was just one of several government-sponsored art programs of the period. Others included the Department of the Treasury's Section of Painting and Sculpture (1934–42; renamed the Section of Fine Arts in 1938), and its Treasury Relief Art Project (TRAP) (1935–38). The WPA Federal Art Project established more than 100 community art centers and galleries throughout the country, researched and documented American design, commissioned a significant body of public art without restrictions on content or subject matter. The project employed more than 5,000 artists and craft workers at its peak in 1936 and probably twice as many over the eight years of its existence. The total federal investment was about $35,000,000. Some of the most important works that came out of these projects were murals in public buildings inspired by the example of the Mexican Muralists. These programs gave an enormous boost to art in America, not least by raising the morale of artists, and are now considered to have been a crucial factor in the explosion of creativity in American art following the Second World War.

Harry Herzog, Forging Ahead. Poster of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), 1930s

poster, exhibition print

United States Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs division

Florence Kawa, The Workers, c. 1935

wall-hanging created for the Milwaukee Handicraft Project, exhibition print

[David Larkin, When Art Worked: The New Deal, Art, and Democracy. New York: Rizzoli International Publications,2009]

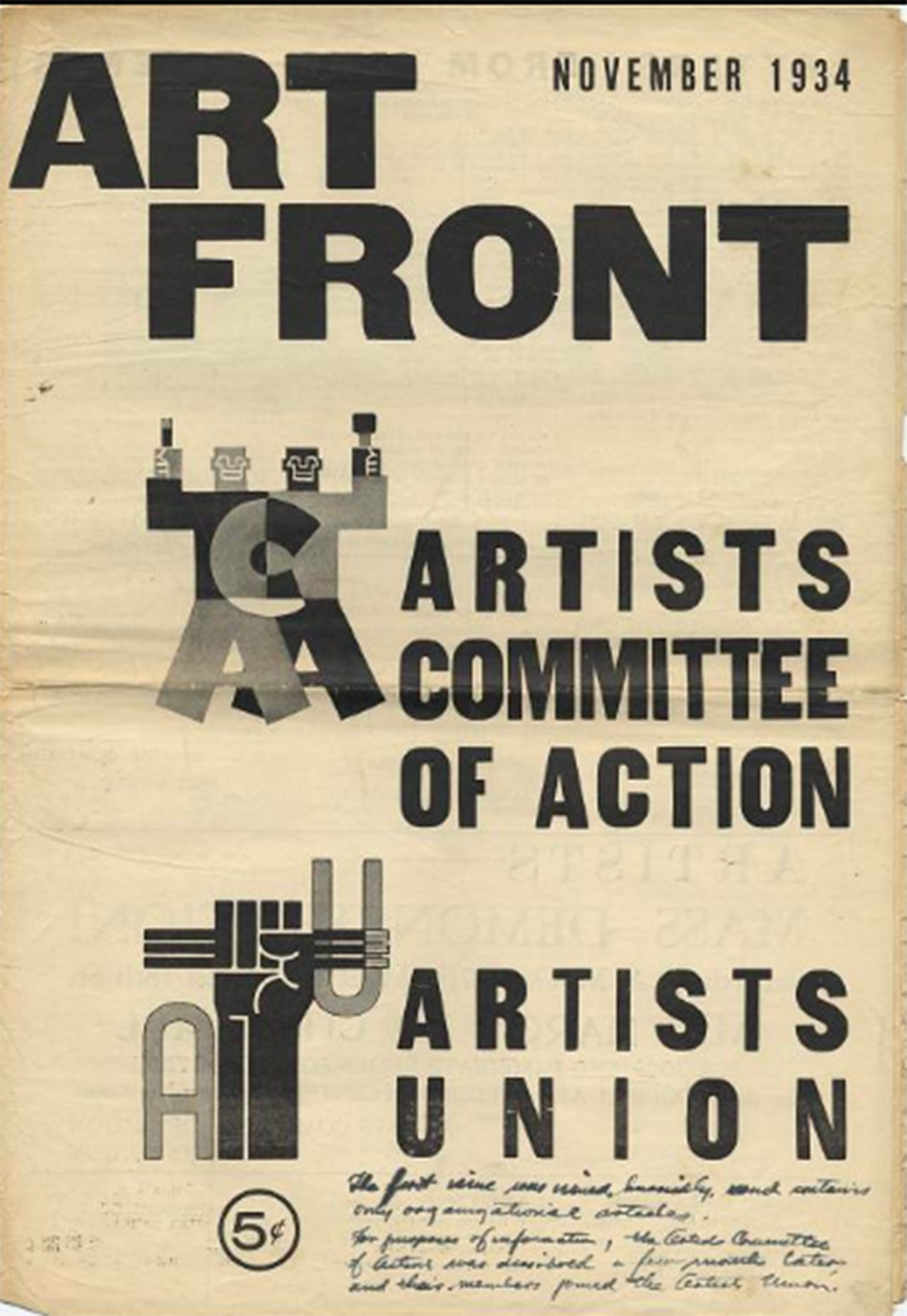

Federal programs such as the Federal Art Project (FAP) were not without fault. The project’s greatest problem was to balance the whims and irregular schedules of the creative process with the rigid timekeeping rules of the WPA/FAP bureaucracy. Furthermore, the work of the artists was still very precarious: the FAP budget was cut several times, eliminating artists from the pay rolls. In an effort to win and increase government patronage, a group of militant artists formed a trade union of painters, sculptors, and print-makers, many of whom were close to or influenced by the Communist Party. The dynamic, colorful Artists’ Union soon became known for its aggressive tactics—engaging in mass picketing, strikes, and sit-ins. Stuart Davis, the first editor for Art Front, wrote: “Artists at last discovered that, like other workers, they could only protect their basic interests through powerful organizations. The great mass of artists left out of the project found it possible to win demands from the administration only by joint and militant demonstrations. Their efforts led naturally to the building of the Artists’ Union.” Others were less apt to pay compliments to these tactics, or to the Artists’ Union: “It was grotesque and an anomaly to have artists unionized against a government which for the first time in its history was doing something about them professionally.” But the Artists’ Union represented the workers’ perspective, not the management’s. They had little faith in the sincerity of government bureaucrats and believed that it was the artists’ job to organize; after all, it was thanks to their lobbying that programs like FPA started in the first place. Members of the Artists Union were active participants in aiding strike lines in New York City, agitating for workers’ rights and demanding better pay. Among other things, they advocated for permanent funding for art, demanded rental fees from museums, and established municipal art centers in urban and rural areas. For three years, between 1934 and 1937, the union published Art Front, probably the liveliest art periodical of the time.

The cover of the first issue of Art Front, the monthly of the Artists’ Union, November 1934

magazine cover, exhibition print

Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington

The Artists’ Union leading a picket line in New York, November 29, 1936

bw. photo, exhibition print

Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington

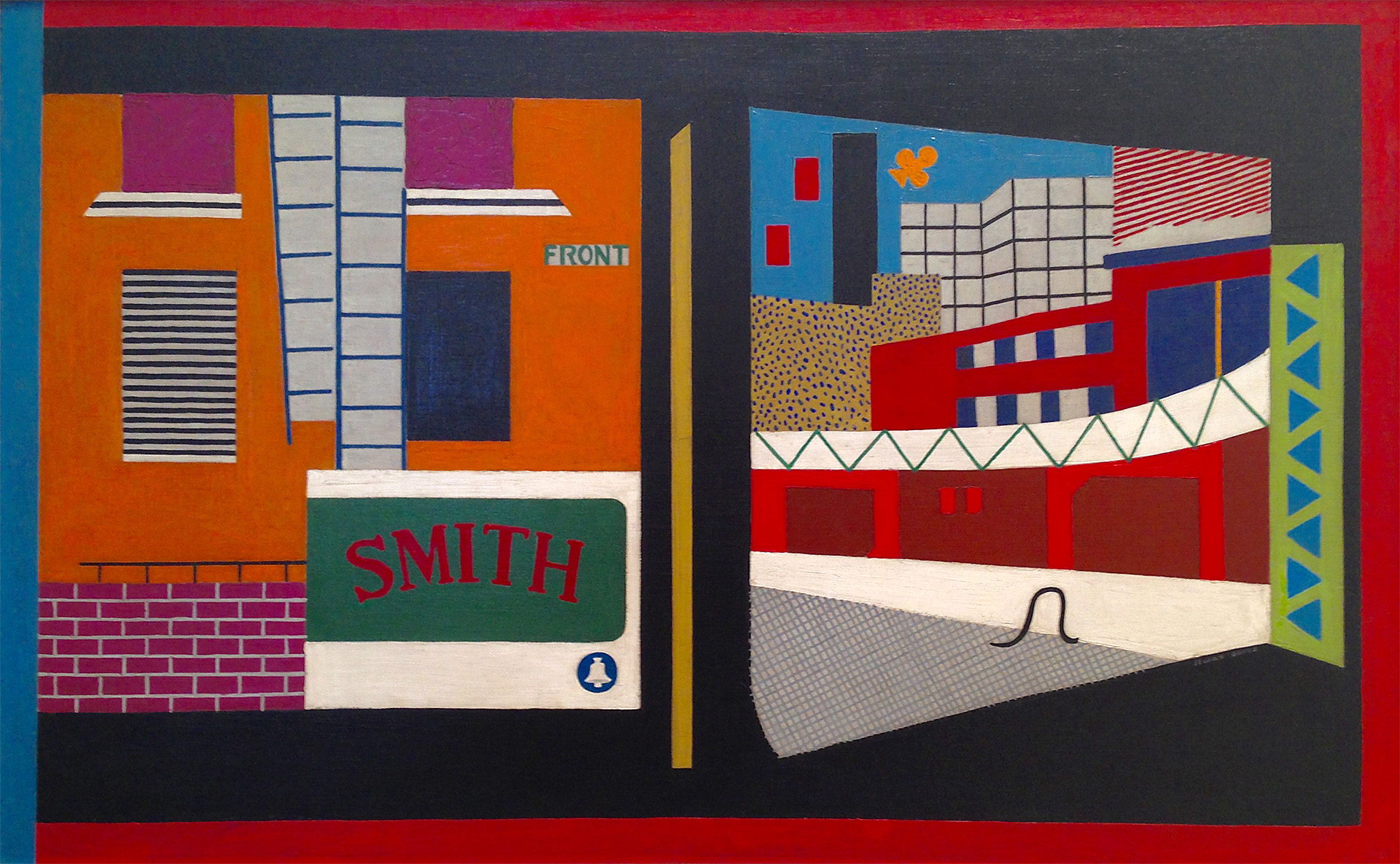

Stuart Davis’ artistic sensibility was formed early on by the revolutionary Armory Show of 1913. By the 1930s, Davis was already a famous American painter, but that did not save him from feeling the negative effects of the Great Depression, which led to his being one of the first artists to apply for the Federal Art Project. Under the project, Davis created some seemingly Marxist works; however, he was too independent to fully support Marxist ideals and philosophies. Despite several works that appear to reflect the class struggle, Davis’ roots in American optimism were apparent throughout his lifetime. He was active in the Unemployed Artists Group, became vice president of the Artists’ Union, and was editor of the organization’s journal Art Front and vice president and then president of the American Artists’ Congress. His paintings in the early 1930s were enlivened with quickly recognizable images of street signs, garage pumps, dock scenes and the New York cityscape.

Stuart Davis, House and Street, 1931

oil on canvas, exhibition print

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, Purchase. © Estate of Stuart Davis

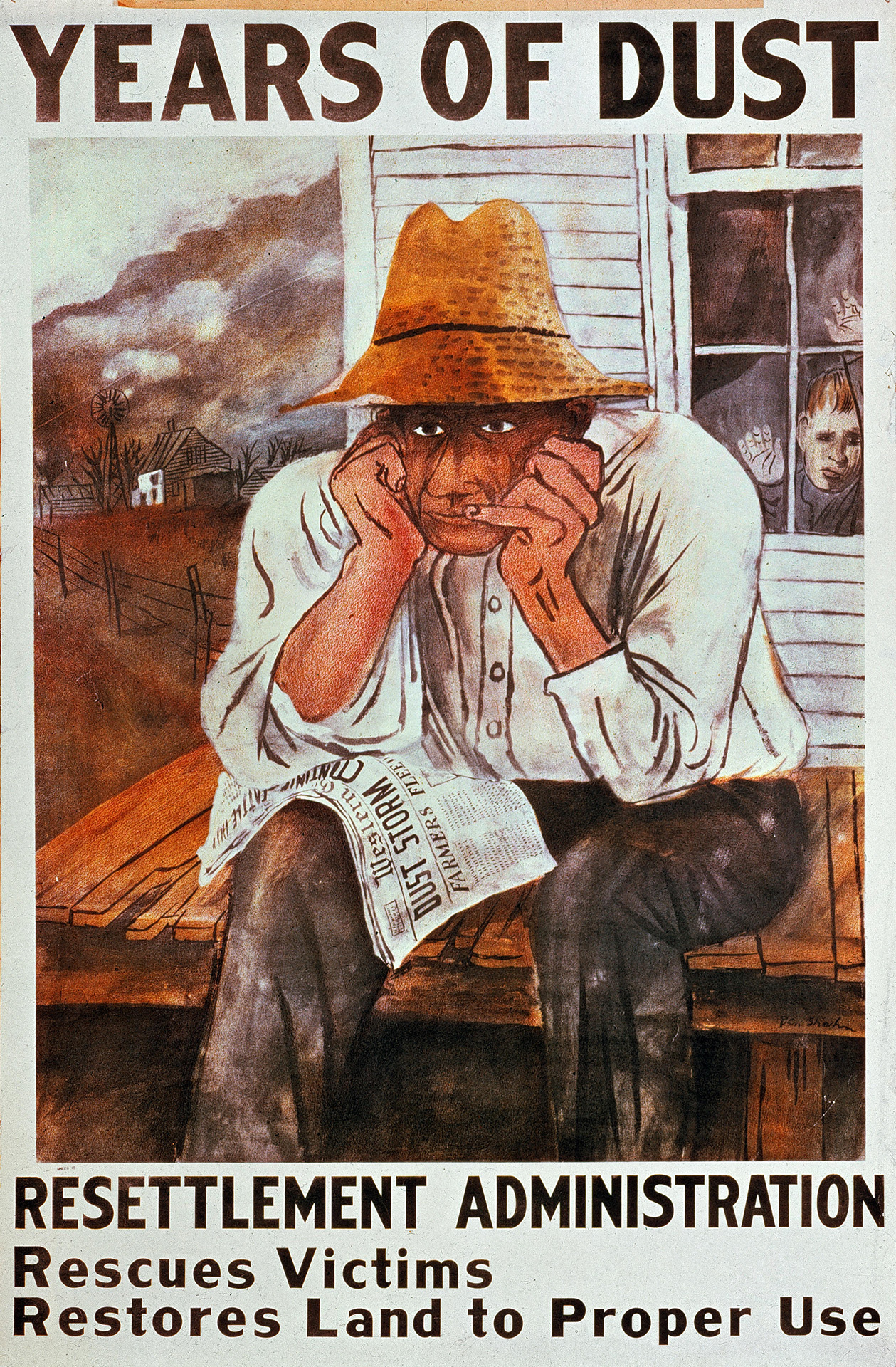

Contrary to Stuart Davis, Lithuanian-born Ben Shahn was among those American artists of the Depression era who turned towards “Social Realism” and were engaged in the great economic and political issues of society. The art period is quite distinct from the Soviet Socialist Realism that was the dominant style in Stalin’s post-revolutionary Russia. Many American artists became dissatisfied with the French avant-garde and wanted to use a style that did not isolate them from greater society. They believed that a more figurative and narrative approach was a more effective weapon to counteract the capitalist exploitation of workers and stem the advance of international Fascism. An apprentice and friend of Diego Rivera, Ben Shahn created many murals for the Federal Art Project. He also worked for the Resettlement Administration, a federal agency that was set up to the help migrant workers fleeing from the so-called Dust Bowl of the Midwest and Southwest of the United States. Ben Shahn brought together different forms of visual culture to break down the barrier between mass media and fine art. In opposition to what Shahn called “the rules for pure art”, the artist consistently inserted words, texts, and quotations into his artwork to emphasize the didactic nature of his art. As he said, “To me, propaganda is a holy word,” and he also created many posters for the different federal agencies he was working for.

Ben Shahn, Years Of Dust, Poster issued by the Resettlement Administration, 1937

poster, exhibition print

United States Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs division

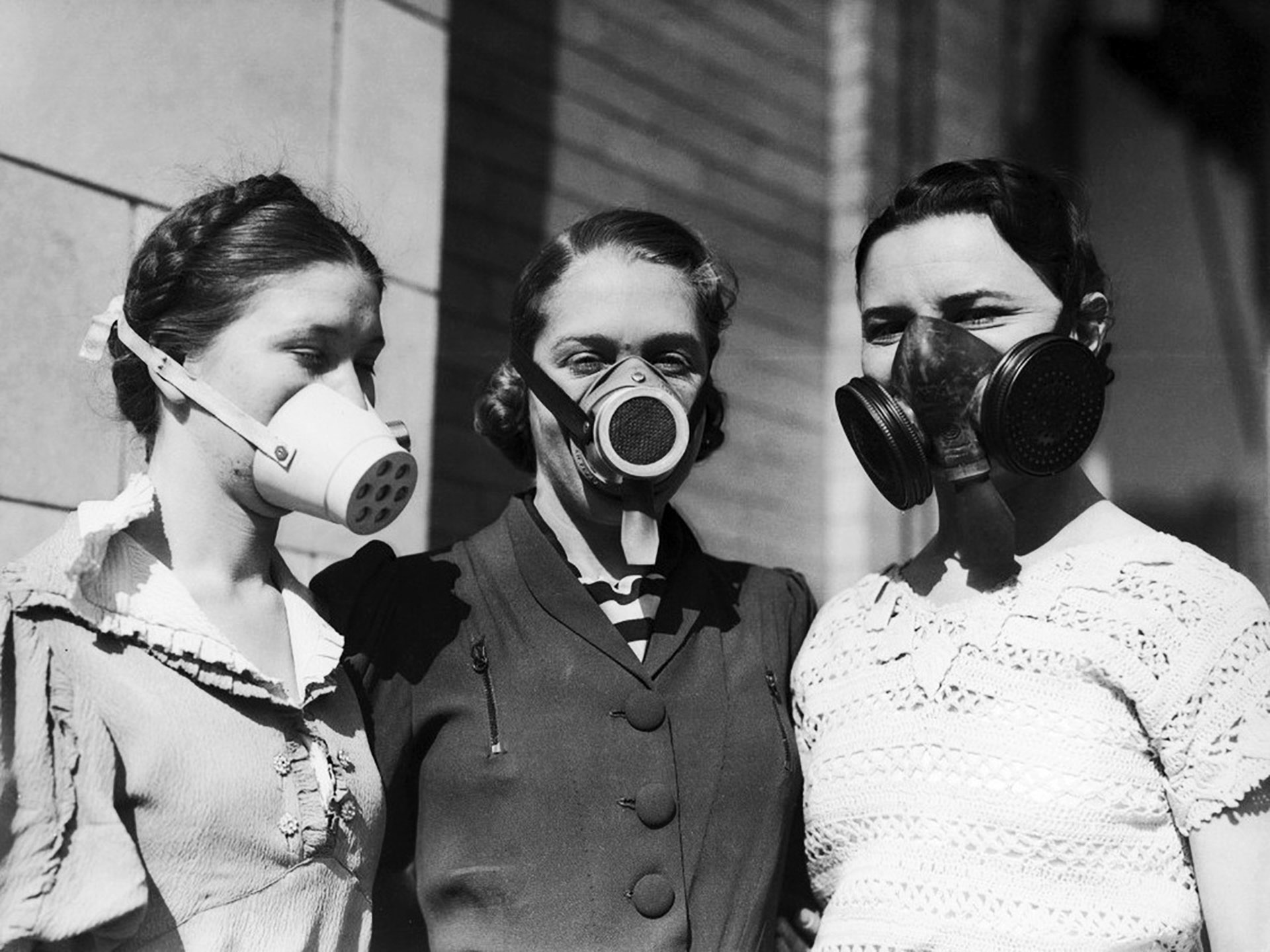

While the member of the Artists’ Union were picketing in New York, fighting for workers’ and artists’ rights, in the Midwest and Southwest of the United States drought and dust storms added to the economic havoc. The heat waves of the mid-1930s were among the most severe in the modern history of the country (until the 21st century). The so-called Dust Bowl of the 1930s caused catastrophic human suffering and enormous economic damage. The disaster was not only caused by the extreme draught, but also by farmers using new technologies to break the hardened soil of the Great Plains and open them to cash-crop agriculture. Due to the lack of crop rotation, the severe, prolonged drought turned the soil into fine dust; and without the native prairie plants to keep it in place, the dust was sucked into “black blizzards”—massive, unpredictable windstorms that derailed trains, suffocated unlucky travelers, and infiltrated every crevice of homes and buildings. Around 7,000 people, including many small children, died of dust pneumonia, and many thousands were left homeless. Some 300,000 men, women, and children migrated west to California, hoping to find work. Broadly, these migrant families were referred to with the derogatory term “Okies” (as from Oklahoma) regardless of where they came from. They traveled in old, dilapidated cars or trucks, wandering from place to place to follow the crops. The Dust Bowl and the Great Depression lasted from 1929 to 1939 and were closely linked, according to environmental historians. As one of these experts said, both events revealed American society’s “fundamental weaknesses” but also offered “a reason, and an opportunity, for substantial reform.”

A dust storm approaches Stratford, Texas, 1935

bw. photo, exhibition print

NOAA – National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, George E. Marsh Album

Young women model masks worn during America’s Dust Bowl disaster, circa 1935

bw. photo, exhibition print

©Bert Garai/Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty

Fires in California

Magyar Világhíradó 614. November 1935

Hungarian, with English subtitles, 0’52”

Hungarian National Film Fund

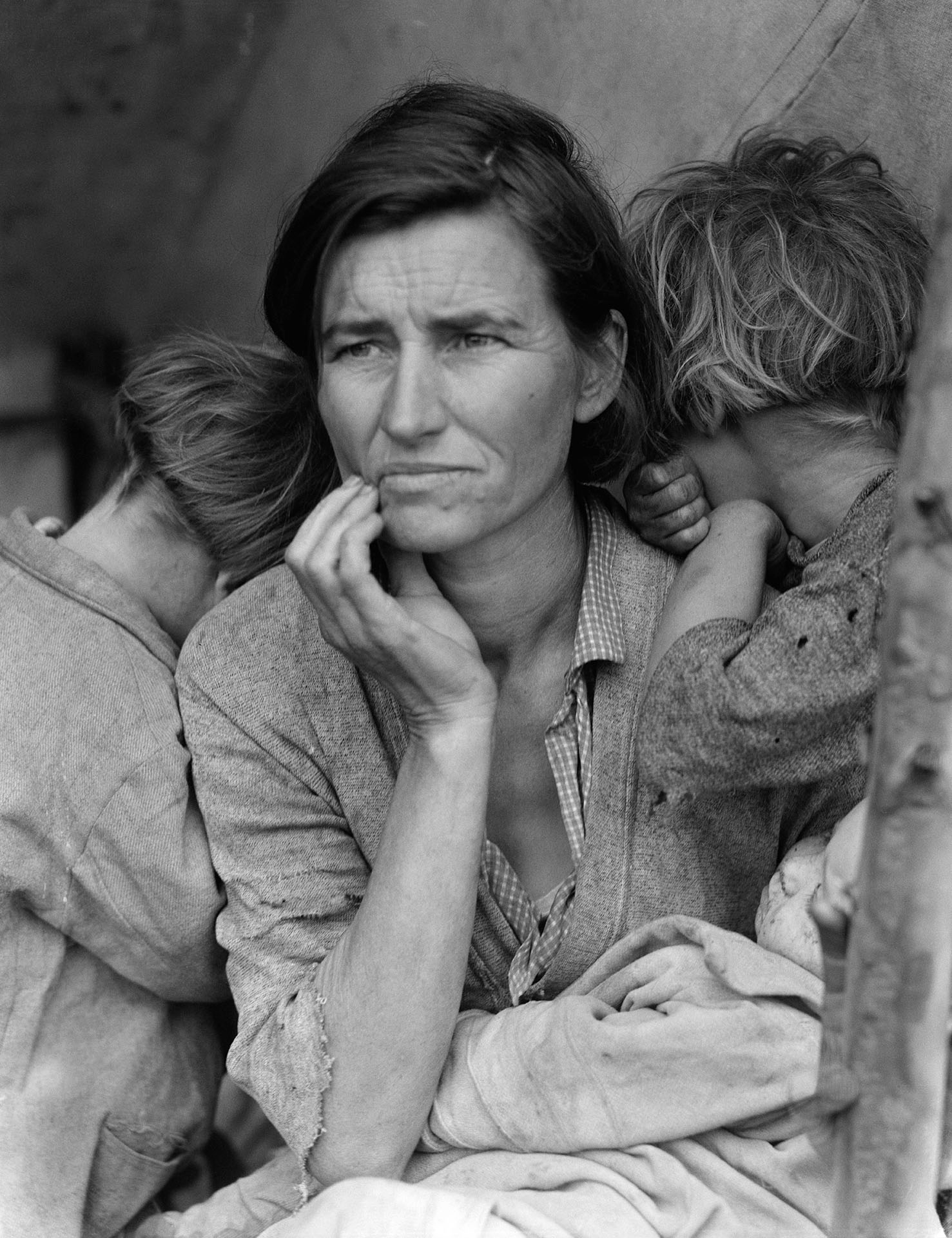

Under the direction of Roy Stryker, the federal Resettlement Administration (RA, later called the Farm Security Administration, FSA), a New Deal agency in the Department of Agriculture, employed photographers—Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, Arthur Rothstein and Russell Lee, among others—who were assigned to document small-town life in the United States and to show how the Federal government was attempting to improve the lives of rural communities during the Depression. Dorothea Lange, however, worked with little concern for the ideological agenda or the suggested itineraries and instead concentrated on getting to know and understand the people she was supposed to photograph. She talked with them while working, putting them at ease and letting them tell their stories. The titles and annotations often reveal personal information about these people, who—thanks to Lange’s sensitivity—are not presented as nameless faces of misery, but as individuals, with whom the viewer also could identify. Lange’s images—and the works of other FSA photographers—brought to public attention the plight of the poor and forgotten: sharecroppers, displaced farm families, and migrant workers. Distributed to newspapers across the country, Lange’s poignant images became icons of the era.

Dorothea Lange, “Dust bowl farmers of west Texas in town”, June 1937

bw. photo, exhibition print

United States Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs division

Dorothea Lange, Drought refugees from Oklahoma camping by the roadside. They hope to work in the cotton fields. There are seven in the family. Blythe, California, 1936

bw. photo, exhibition print

United States Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs division

“I saw and approached the hungry and desperate mother, as if drawn by a magnet. I do not remember how I explained my presence or my camera to her, but I do remember she asked me no questions. I made five exposures, working closer and closer from the same direction. I did not ask her name or her history. She told me her age, that she was thirty-two. She said that they had been living on frozen vegetables from the surrounding fields, and birds that the children killed. She had just sold the tires from her car to buy food. There she sat in that lean-to tent with her children huddled around her, and seemed to know that my pictures might help her, and so she helped me. There was a sort of equality about it.”

(Dorothea Lange in Popular Photography, February 1960)

Dorothea Lange, “Mother of Seven Children”, Florence Owens Thompson, Destitute Pea Pickers in Nipomo, California, 1936

bw. photo, exhibition print

United States Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs division

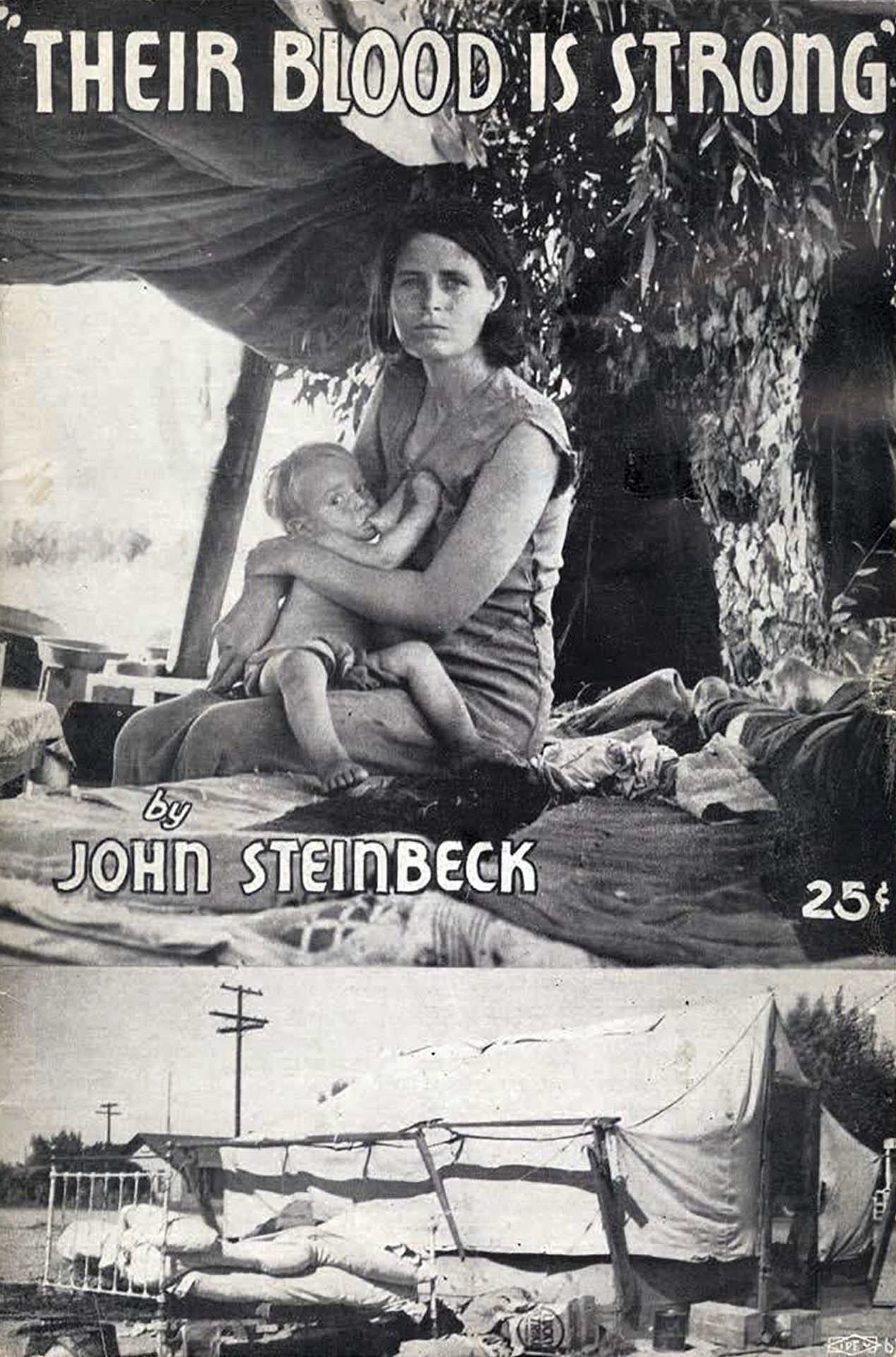

The series of articles The Harvest Gypsies by John Steinbeck focused on the lives of migrant workers who fled the draught in Texas, Oklahoma and other Southern states and tried to make ends meet in California Central Valley. The series was commissioned by the San Francisco News, where it was published daily between October 5–12, 1936; later the seven articles of the series were published along with Steinbeck’s epilogue Starvation Under the Orange Trees and twenty-two photographs by Dorothea Lange. The pamphlet was published by the Simon J. Lubin Society, a non-profit organization dedicated to educating Americans about the hardships of the migrant workers.

John Steinbeck, Their Blood is Strong, 1936

pamphlet cover, exhibition print

published by the Simon J. Lubin Society / wikimedia commons

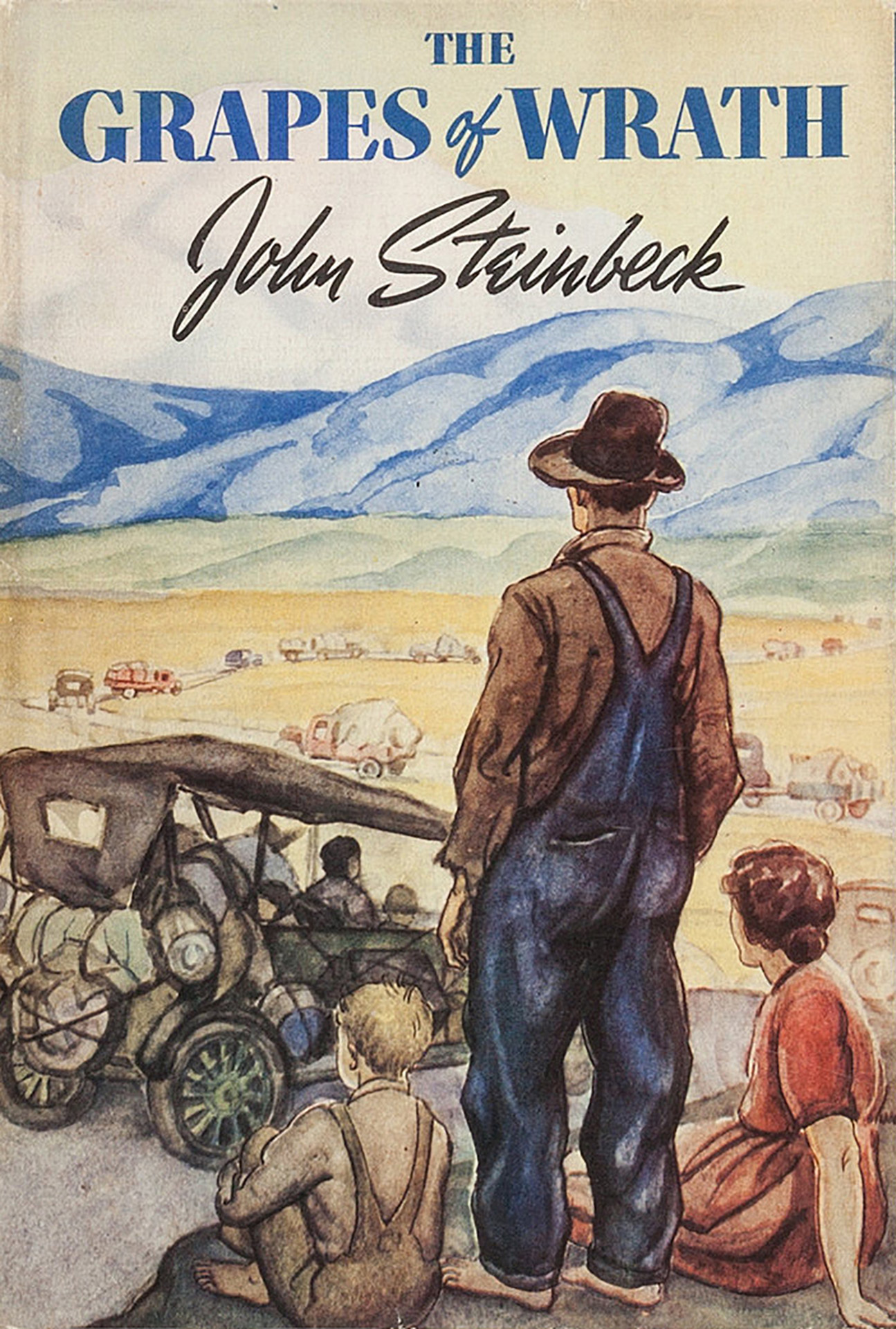

Set during the Great Depression, The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck focuses on the desperate situation of workers, who had to leave their home behind because of the unbearable living conditions caused by the unfortunate mixture of the financial crisis and the Dust Bowl. The novel presents a tenant family from Oklahoma, who, like other “Okies” were forced to leave their home to make ends meet in California as migrant workers, seeking jobs, land, dignity, and a future. Steinbeck developed the novel from The Harvest Gypsies, and he also used field notes taken during 1938 by Farm Security Administration worker and author Sanora Babb. While she collected personal stories about the lives of the displaced migrants for a novel she was developing, her supervisor, Tom Collins, shared her reports with Steinbeck, who at the time was working for the San Francisco News. Babb’s own novel, Whose Names Are Unknown, was eclipsed in 1939 by the success of The Grapes of Wrath and was shelved until it was finally re-published in 2004, a year before Babb’s death. When preparing to write the novel, Steinbeck wrote: “I want to put a tag of shame on the greedy bastards who are responsible for this the Great Depression and its effects.” He famously said, “I’ve done my damnedest to rip a reader’s nerves to rags.” At the time of publication, Steinbeck’s novel “was a phenomenon on the scale of a national event. It was publicly banned and burned by citizens, it was debated on national radio; but above all, it was read”. Many of Steinbeck’s contemporaries attacked his social and political views; he was considered as a propagandist. In any case, The Grapes of Wrath won a large following among the workers, due to Steinbeck’s sympathy for the most vulnerable groups of American society.

John Steinbeck, The Grapes of Wrath, 1939

first edition dust jacket cover (design by Elmer Hader), exhibition print

New York: Viking Press / wikimedia commons