In 1935, Korunk [Our Time], the left-wing literary journal of the Hungarian community living in Transylvania, published a long exposé on the works by French writer, André Malraux. According to the author of the essay, Malraux presents “the real drama of the colonies, while he also introduces the grave experience of a continental turmoil into the imaginative rebellion of literary youth.” Beside the novel La Condition humaine, [Man’s Fate, 1933], the article also mentioned Malraux’s latest work, Le Temps du mépris [The Days of Wrath, 1935], in which he tells a story of the underground resistance to the Nazis within Hitler’s Germany. “This story (which is based on the trip to Germany that he made to save Dimitrov), is a monologue of the distressed individual with a deep experience of prison; within and above him is the desire to sacrifice himself and struggle for solidarity.” Malraux was among those left-wing French intellectuals who formed the Association des Écrivains et Artistes Révolutionnaires [AEAR – Association of Revolutionary Artists and Writers], an organization set up to fight against Fascism and for “the Defense of Culture.” Anti-Fascism became the common ground on which the Popular Front governments of France and Spain could emerge in 1936, despite the ideological differences of their respective constituent entities. In a country like Hungary, where the so-called Hazafias Népfront [Patriotic People’s Front] was active during the Communist regime, the notions of anti-Fascism and the Popular Front are considered as part of a larger scheme of Communist propaganda, and figures like André Malraux are held as truthful followers of a Stalinist agenda. As much as the Popular Front idea gained from the resolutions of the 7th Congress of the Communist International (Comintern) in 1935, European intelligentsia was striving for a united front of left-wing parties and organizations long before the official Communist policies changed in this direction. The growing tensions in European politics, as well as the threat of the rapid spread of Fascist and Nazi ideas in almost all countries of Europe, warned many intellectuals that the conflict between left-wing parties was futile and dangerous. Attila József was among these intellectuals who pleaded the importance of a united front. However, he was heavily criticized because of the political essay Az egységfront körül [On the United Front, 1933] by the narrow-minded Muscovite leaders of the Hungarian Communist Party (KMP), which was a consequence of his leaving the Party. And despite Malraux’s evident Marxist sympathies and his bitter criticisms of Fascism, Le Temps du mépris was the only one of his books that was allowed to be published inside the Soviet Union.

In fact, anti-Fascism began where Fascism began, in Italy, with the Arditi del Popolo [“The People’s Daring Ones”] who famously swam across the Piave River with daggers in their teeth. The Arditi del Popolo brought together unionists, anarchists, socialists, communists, republicans and former army officers. From the outset, anti-Fascists began to build bridges where traditional political groups saw walls. While the German Roter Frontkämpferbund [RFB, Red Front Fighters’ League], (which from 1932 became known as Antifaschistische Aktion, or “antifa” for short), was indeed the paramilitary organization of the German Communist Party [KPD, Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands], the famous clenched-fist salute they began to use was picked up as a universal symbol of the fight against intolerance, and was used by anarchists, radicals, civil right activists and all kinds of organizations alike throughout the 20th and 21st century. The symbol of the clenched fist was also adopted by the Popular Front government of France and by the Republican fighters of the Spanish Civil War. Furthermore, it became the logo of the left-wing Artists’ Union in the United States. The language of anti-Fascism was just as universal as the language of Fascism, and it connected all kinds of intellectuals from the political spectrum of the Left.

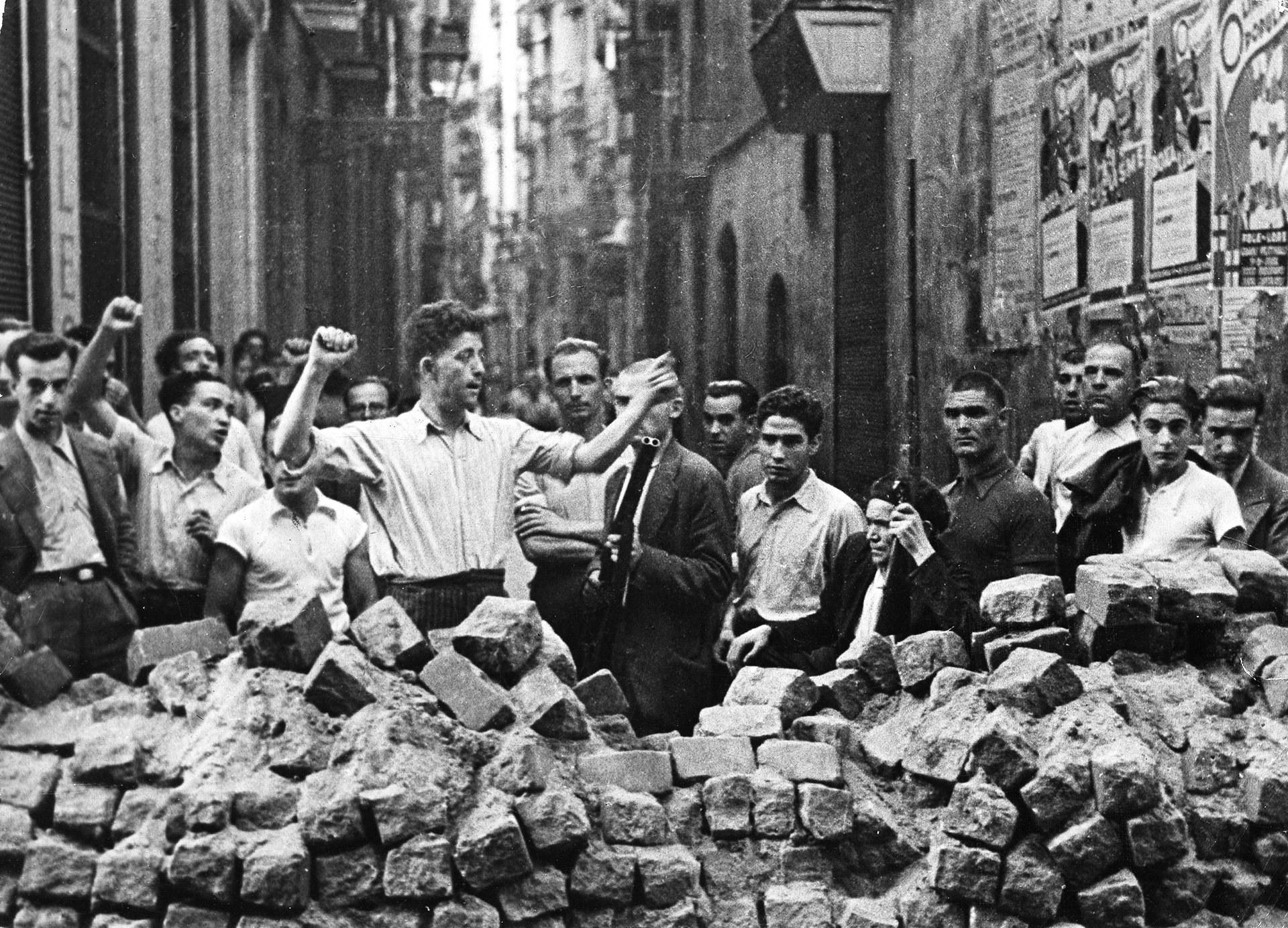

Some historians have emphasized the prior loyalty of Communist supporters of the Popular Front to the Stalinist regime in the USSR, and have explained their new-found faith in democracy as, indeed, a mere “tactical camouflage” (a view given retrospective weight by the 1939 Nazi–Soviet Pact). Conversely, some historians have chosen to see in the militancy of rank-and-file supporters of the Popular Fronts, and in the volunteers who went to fight with the International Brigades in the Spanish Civil War, the manifestation of a genuine passion for democracy that had its roots in a tradition of popular radicalism. For Stalin, the French Front Populaire or the Spanish Civil War were indeed only testing grounds for how to turn popular democracies into Communist dictatorships in Europe, or in the regions where his hand would reach. Yet, the majority of the left-wing artists and writers who supported the cause of a united front against Fascism—like Malraux, Bertolt Brecht, Antonio Machado, or Attila József—also had their doubts about the Stalinist system, and, with few exceptions, they were even less inclined to follow the Stalinist aesthetic of Socialist Realism. On the grounds of an “anti-Fascist minimum”, they were more concerned about the enormous social inequalities, which were amplified by the Great Depression, and the severe political tensions in their respective countries.

Gisèle Freund, André Malraux at the First International Congress of Writers for the Defense of Culture at the Palais de Mutualité, Paris, France, 1935

bw. photo, exhibition print

© Gisèle Freund

German anti-Fascists (Roter Frontkämpferbund / Rofront) give the clenched fist salute, 1928

bw. photo, exhibition print

©Fox Photos/Getty Images

Membership card of the Artists’ Union, 1935

ephemera, exhibition print

Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington

Workers on strike on the construction site of the International Exhibition at the Trocadéro, Paris, 1936

bw. photo, exhibition print

Süddeutsche Zeitung Photo / Alamy

Republican (Loyalist) forces set up barricades in Barcelona during the Spanish Civil War, July 20, 1936.

bw. photo, exhibition print

ullstein bild