In the words of literary historian Pál Ács, “...Attila József’s national, patriotic poetry of incomparable beauty is structured around the themes of his own—if you like, evangelical—poverty. It is not the poet who is the reason why ‘national poverty’ is still a threat today." For Attila József, the homeland also evidently meant all those places (abandoned factory yards, gloomy suburban plots), phenomena (unemployment, social injustice) and people (the poor, the suffering) that never were and never are welcome by the authorities.

The period of the poem “A Breath of Air!” in Hungary was, of course, not as dark for everyone as Attila József wrote in his poems. The country had more or less recovered from the economic crisis, and the beneficial veil of the economic boom masked the discontent of those in the depths of society. It is no coincidence that, looking back from today, the face of the era that comes to the fore is one of “peaceful, bourgeois” nostalgia: the world of the new Hungarian sound movies and picture magazines, where little was said about the excesses of power or social injustice. As the historian Ignác Romsics wrote, the “Hungarian system of government of the period is considered to be a limited form of parliamentarism, i.e. one that also contains authoritative elements... The view that considers this system of government to be a totalitarian state of the Nazi or fascist type ignores certain basic facts, as does the view that juxtaposes it with the parliamentary democracies of England, France, Scandinavia or even Czechoslovakia. The Hungarian system, like most Central and Eastern European regimes, is characterized by its transitory nature and by the ‘hybridity’, which is most often described in international literature as authoritarian.”

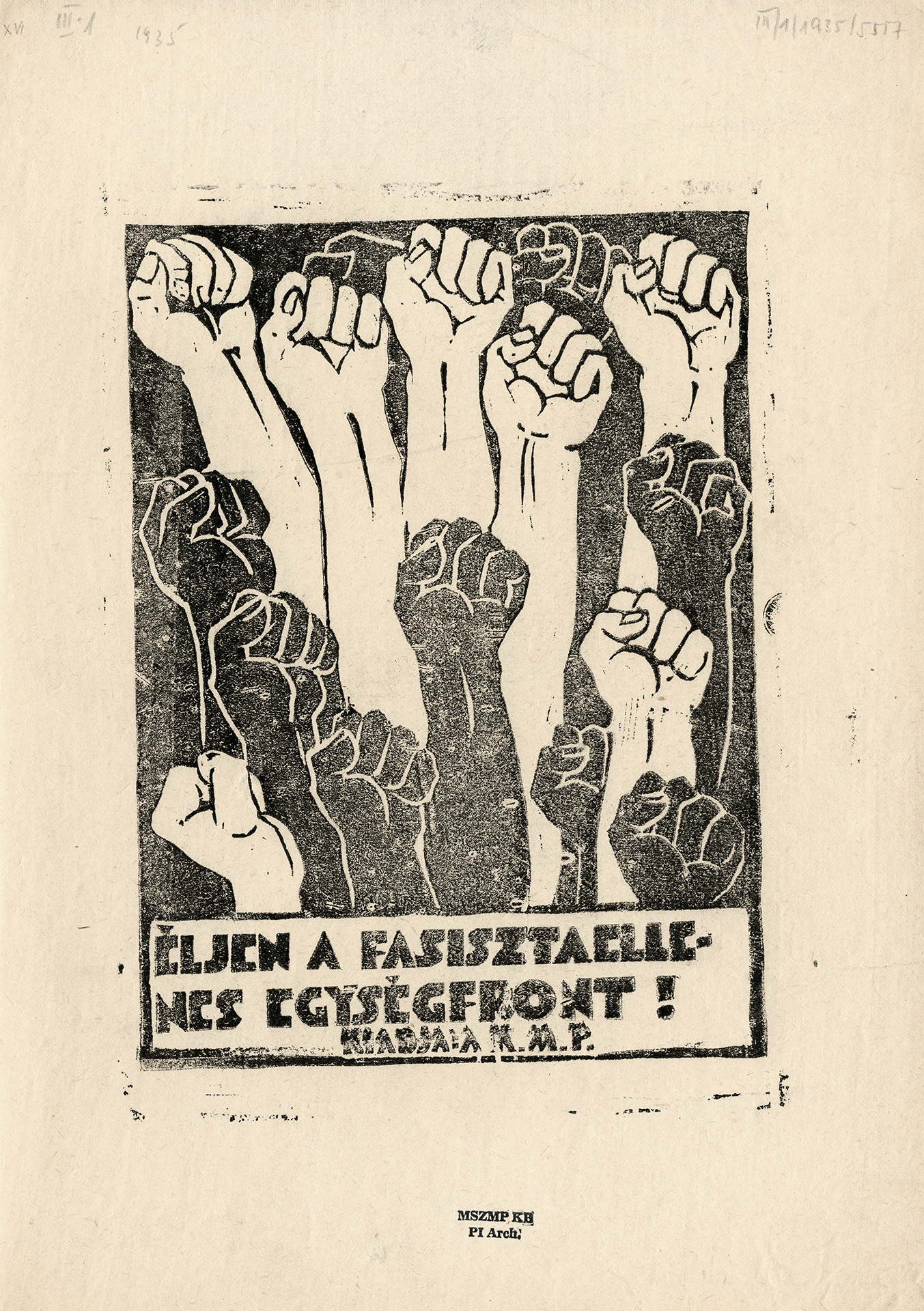

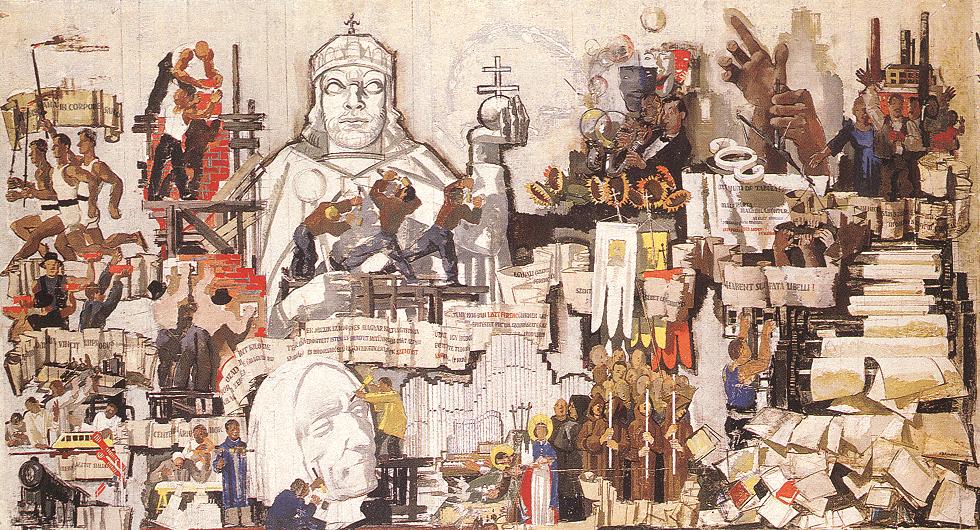

Several proposals were made to solve the problems: the National Work Plan of Prime Minister Gyula Gömbös; or the Communist Party, which was operating illegally at the time; and the emerging extreme-right parties made different and disparate proposals to remedy the country’s problems. But Hungary has always been in the grip of various great powers, while global politics and the global economy have had a huge impact on domestic processes. Various ideological trends have also infiltrated the sphere of culture, where numerous debates and fronts have emerged among its actors. Like today, there was little transition between the two sides, but there were also many artists who worked tirelessly to reconcile folk and national traditions with progression, and create a world where people of different minds can peacefully live together.

These days any evaluation of the Horthy era, and within that of the Gömbös government, is conducted within an extremely complex interpretive framework fraught with highly charged political and social debates. An unbiased interpretation is—paradoxically—hampered by the historical perspective: the Second World War and the Holocaust, as well as the Soviet occupation and Communist rule in Hungary retroactively shape our conception of this historical period. Many historians and experts try to judge this era based on their own current political affiliation, ideological disposition, temperament, or even events in their own family history. Our knowledge in hindsight thus settles on this era, which, like almost every period in history, had contradictions and uncertainties rather than definite outlines for those who lived through it.

An in-depth study of contemporary sources is therefore important, and this is why contemporary authors who, due to their artistic sensitivity or professional expertise, had a better understanding of all the social and political processes that remained mostly hidden from ordinary people, can play a special role in interpreting the era. Furthermore, it is especially important to critically compare these contemporary sources with each other. In interpreting the Horthy era, these authors should be read side by side, so to speak, “closely”. One such author is Gyula Szekfű, whose book of 1934 Három nemzedék és ami utána következik [Three Generations and What Follows] describes Hungarian society after the Treaty of Trianon, which itself had a significant influence on the ideological atmosphere of the period. In this book, Szekfű, in a much-criticized way, focused primarily on describing the situation of the social elite. Today, Szekfű is seen by many—quite correctly—as an historian who served several political courses. His above-mentioned work is considered by many—also justly—as downright “soul-poisoning” due to its anti-Semitism. But his anamnesis of the “neo-Baroque world” of the Horthy era is very much to the point, as this term provides a particularly impressive critique of the period. With “neo-Baroque” Szekfű defined the nobility-obsessed, authoritarian, deeply hierarchical mentality and political values that were characteristic of the era. According to Szekfű, there was no real mobility in the society of his time; as he writes, “neither the social division nor the social thinking has changed much; and everything in this field has remained as people were accustomed to during the third generation”.

The Horthy regime remained essentially unchanged during a period of constant—economic, political and social—change. Gömbös and his government started out in the spirit of change and won over the masses with their ostentatious reform policy. However, in addition to the economic successes, it is also worth noting the voices that call attention to the restrictive-repressive features of the regime. In assessing Gömbös’s achievements as Prime Minister, in addition to monitoring macroeconomic data and the development of external relations, it is therefore worthwhile to draw on these sources. It is instructive, for example, how similarly the conservative, “bourgeois” writer, Sándor Márai and the left-wing poet, Attila József described the “filing” practice of the Gömbös government: how the governing party (the National Unity Party, NEP) collected data on voters.

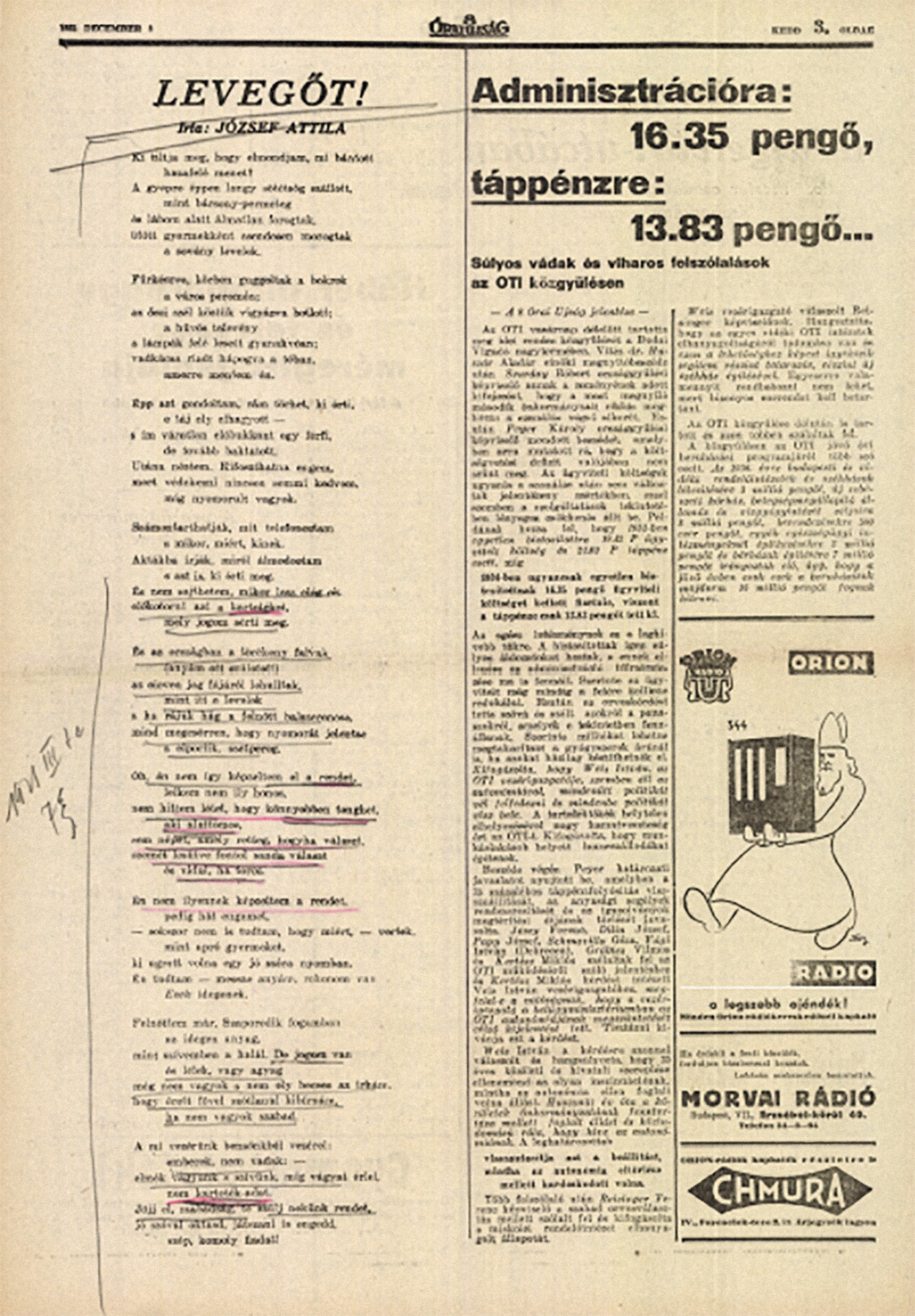

As the literary historian Miklós Szabolcsi, Attila József’s monographer, wrote, “The poem A Breath of Air! [Levegőt!] was originally an ‘occasional poem’“. The occasion was the election of 1935, when Endre Bajcsy-Zsilinszky, the joint candidate of the opposition parties “was overthrown by open threats, the deployment of gendarmes and bribery in favour of the pro-government candidate.” The poet’s original intention was indeed to write an occasional poem, but it turned out to be something quite different—a universal exclamation, or as Szabolcsi puts it, an “ode to freedom.” The poet originally titled the poem “Rend és szabadság” [Order and Freedom], and only changed it to “A Breath of Air!” on the advice of the editor of the newspaper (8 Órai Újság [8 O’clock News]) that published it. Indeed, the poem makes many references to the immediate political context: the image of the “fragile villages” that “have fallen from the tree of living rights” is a reference to electoral fraud, but it also indicates the enormous differences in social and political opportunities between rural and urban areas. One of the important themes of the poem is the “filing” practice of the ruling party (Nemzeti Egység Pártja, Party of National Unity, NEP): the party collected data on voters and used it successfully during the elections. This practice was sharply criticized by several intellectuals at the time, for instance by the conservative, “bourgeois” writer, Sándor Márai who, very much like Attila József, described this practice as a threat. But the poem does not stop at topicality: its universal message, its categorical stand for freedom, is as intelligible today, in the age of surveillance capitalism and newer types of hybrid regimes, as it was at the time of its writing.

A Breath of Air!

Who can forbid my telling what hurt me

on the way home?

Soft darkness was just settling on the grass,

a velvet drizzle,

and under my feet the brittle leaves

tossed sleeplessly and moaned

like beaten children.

Stealthy shrubs were squatting in a circle

on the city’s outskirts.

The autumn wind cautiously stumbled among them.

The cool moist soil

looked with suspicion at streetlamps;

a wild duck woke clucking in a pond

as I walked by.

I was thinking, anyone could attack me

in that lonely place.

Suddenly a man appeared,

but walked on.

I watched him go. He could have robbed me,

since I wasn’t in the mood for self-defense.

I felt crippled.

They can tap all my telephone calls

(when, why, to whom.)

They have a file on my dreams and plans

and on those who read them.

And who knows when they’ll find

sufficient reason to dig up the files

that violate my rights.

In this country, fragile villages

– where my mother was born –

have fallen from the tree of living rights

like these leaves

and when a full-grown misery treads on them

a small noise reports their misfortune

as they’re crushed alive.

This is not the order I dreamed of. My soul

is not at home here

in a world where the insidious

vegetate easier,

among people who dread to choose

and tell lies with averted eyes

and feast when someone dies.

This is not how I imagined order.

Even though

I was beaten as a small child, mostly

for no reason,

I would have jumped at a single kind word.

I knew my mother and my kin were far,

these people were strangers.

Now I have grown up. There is more foreign

matter in my teeth,

more death in my heart. But I still have rights

until I fall apart

into dust and soul, and now that I’ve grown up

my skin is not so precious that I should put up

with the loss of my freedom.

My leader is in my heart. We are

men, not beasts,

we have minds. While our hearts ripen desires,

they cannot be kept in files.

Come, freedom! Give birth to a new order,

teach me with good words and let me play,

your beautiful serene son.

November 21, 1935

Translated from the Hungarian by John Bátki.

(Winter Night. Selected Poems of Attila József.

Oberlin College Press, 1997.)

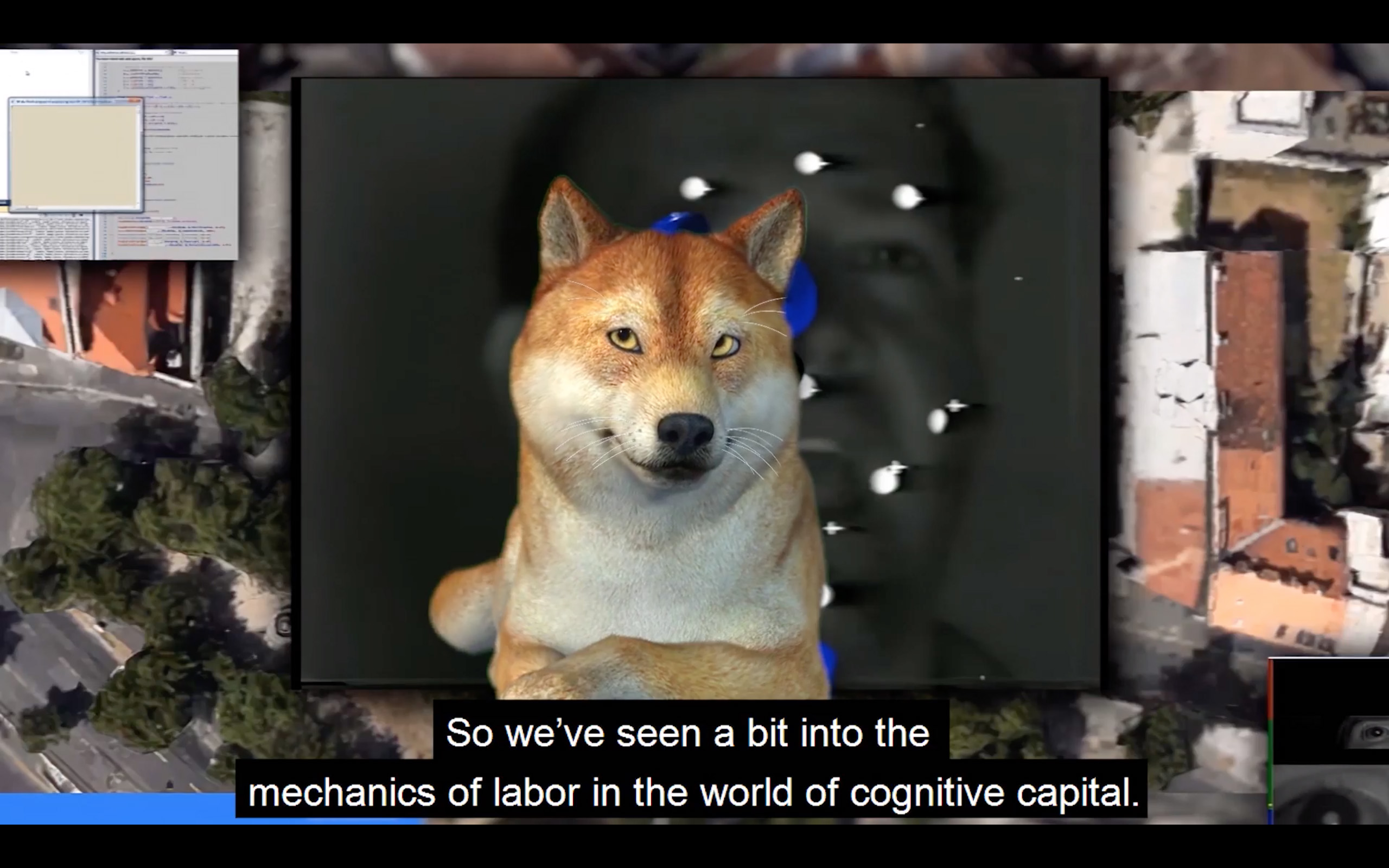

The main motif of the poem Inhale! by Attila József is surveillance: among other things, in his poem the poet steadfastly protested against the practice of the Gyula Gömbös-led National Unity Party of keeping records on voters. But surveillance is not only a problem of autocratic regimes, what is called surveillance capitalism has become a serious political and economic issue in the 21st century.

Tamás Páll’s Self Spam Simulation (S.S.S.) of 2016 is an immersive multimedia room installation that invites viewers into the prolific world of online surveillance. The installation aims to form a picture the social effects of 21st century technology-based surveillance and data markets and their philosophical interpretations from diversified and arbitrary perspectives in the mid-2010s. The project Reaction (2021) presented by OFF-Biennale takes this idea even further as a multimedia reaction to the installation Self Spam Simulation (S.S.S.).

The secret police of the Horthy era (and within that, the Spherical Government) paid close attention to controlling political extremists. However, the Royal Hungarian State Police did not succeed in liquidating both sides of the political spectrum—the Communists and the various party formations of the Hungarist movement—with exactly the same efficiency. The head of the political police was Deputy Chief Captain Imre Hetényi, who had led the area since the mid-1920s. Under the leadership of Hetényi, the Political Police Department pushed back illegal left-wing movements on all fronts by the mid-1930s. After the infamous bomb attack of the railway bridge at Biatorbágy in September 1931, a state of siege was proclaimed and a nationwide man-hunt for KMP-activists was unleashed. Two leaders of the Party, Imre Sallai and Sándor Fürst were captured, sentenced to death and executed in a martial law procedure in 1932, although they (or the Party) had nothing to do with the bomb attack. Most of the KMP-activists were also detained (like Mátyás Rákosi or Zoltán Vas) or were forced to emigrate. During the continuous raids, Attila József also “got busted” in February 1933: in connection with a Communist movement organized among the university youth, where he was accused of “demanding and exciting the violent overthrow of the legal order of the state and society” with his poem Lebukott [Busted]. (The case had no major consequences for him).

While this way the police successfully repressed various left-wing organizations, , they were unable to take effective action against the Arrow Cross and far-right organizations that became active in the mid-1930s. But it was not Hetényi’s fault; he also tried to take action against the Arrow Cross and other National Socialist-inspired organizations with the full rigor of the law. However, the actions sparked attacks by far-right forces. German-friendly politicians and members of the state apparatus sympathetic to the Arrow Cross (several members of the General Staff and the Army, as well as the commanders of the gendarmerie) expected the realization of the Hungarian revisionist goals only from Nazi Germany. Nor could the conservative government elite entirely escape this. The “fascization” experienced in Hungarian domestic politics became decisive in the operation of the state to such an extent that it even reached the position of the powerful police chief, Imre Hetényi. The organizer of the Political Law Enforcement Department was sent into retirement in 1938.

The utopian impetus of the avant-garde was broken by the realities of the 1930s. Many avant-garde artists were chased away or crushed by the various regimes of the 20th century. In this moment of crisis, some artists retreated to their ivory towers, focusing on the matters of their own métier. Others decided to join forces with the political powers they still believed in, often at the cost of losing their artistic integrity. And some continued to believe that the world can be changed through their words and works. And what can be said about the impetus of the socially-engaged art of the 21st century? In our moment of crisis, do artists decide to stay out of socio-political issues that—as individuals—they do not have any major influence over? Or do they still believe that art can have a say in these matters? Do they still bother?

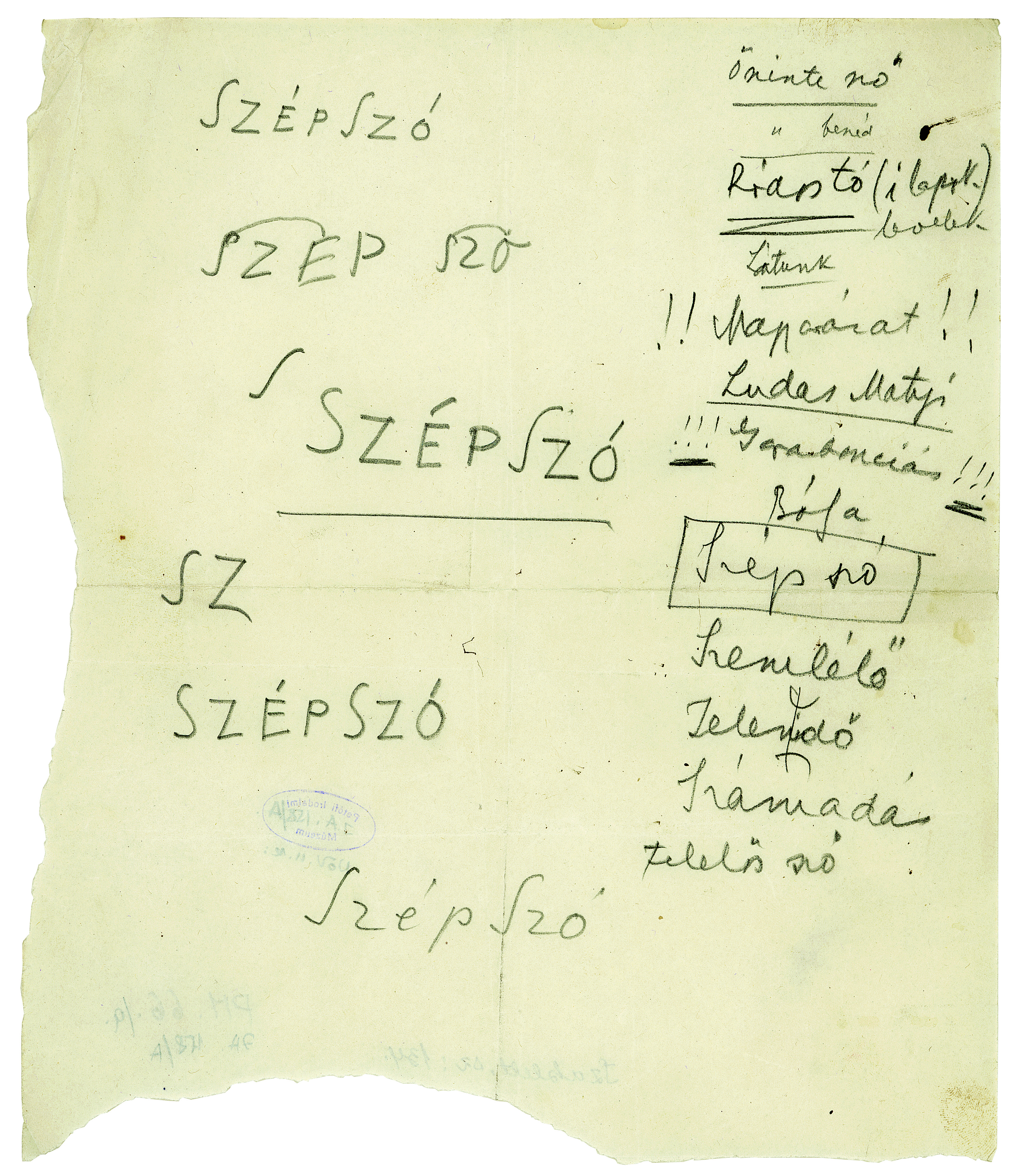

In his final years, after his departure from the Communist Party, Attila József was welcomed by the group of radical-progressive writers (Pál Ignotus and his circle), with whom he became close during the so-called népi–urbánus vita [the debate between “populist” or “folk” writers and the “urban”, progressive writers]. Together they launched the magazine Szép Szó [Beautiful Word] at the end of 1935, of which Attila József became co-editor-in-chief with Ignotus. The literary and social science journal, which was active between 1936 and 1939, did not outlive the poet for long, as its left-liberal ethos became less and less in tune with the prevailing ideology of the period. As the Attila József-researcher, György Tverdota wrote on the occasion of the seventy-fifth anniversary of the launch of the journal, “The poems, short stories, essays, studies, reviews and articles, the sparkling debates published in the journal testify to lasting literary values—and not only those of Attila József. The journal covered topics that are still considered as sensitive topics even today: socialism, leftism, different models and interpretations of liberalism, the nature of the capitalist system, fascism and race theory, the so-called népi-urbánus debate, Freudianism, the national tradition, the literary canon, etc. This thematic, conceptual and aesthetic richness is so up-to-date, that, ‘unfortunately’, it is easy to compile such a collection of quotations from the journal’s texts that is still strikingly topical in 2011.” One of these texts, which is still worth re-reading in 2021, is Attila József’s Szerkesztői üzenet [Editor’s Note], published in the second issue of the journal. The Editor’s Note is, on the one hand, a message written to one of his deeply religious friends and constant debating partners, István Barta, but it is in fact a summary of Attila József’s artistic thinking and the mission statement of Szép Szó, in which he speaks out in favor of artistic freedom, reason, “persuasion, mutual recognition and discussion of human interests”, in an age in which there was less and less room for these ideas.

Editor's Note

Szép Szó [Beautiful Word], 1936:2, excerpts

“You are enthusiastic about the ideal of order, but what you really mean is an ‘orderly state’. But you, who are looking at it from the point of view of moral freedom, must know that order can only express itself on the grounds of freedom and in freedom. […] Finally, you object to the title of this journal. BEAUTIFUL WORD—a phrase which, in your eyes, ‘degrades’ our thoughts into a child’s play in an age of ‘moral regeneration’. I do not see why play or the joy of children, should be inferior. I feel like a child in my happy moments, and my heart is light when I discover play in my work. I am afraid of people who do not know how to play, and I will always strive to ensure that people’s playfulness is not diminished, and that the scanty conditions of life, which discourage and spoil playfulness, are eliminated. In the climate of dictatorships, it is fashionable to denigrate as ‘beautiful or fine words’ all the manifestations of intellectual humanism which have been brought to light by a great deal of suffering and effort and which float before us as principles of our culture. When we want to express, with beautiful words, the human consciousness that the violence— that is taking place all over the world—is forcing into the depths of souls, we cannot acknowledge the spiritual superiority of violence by running away from the beautiful word it mocks. We are willing to endure this mockery. ‘Beautiful word’ in Hungarian does not mean a polished, well-ornated expression, but an embodied argument. The beautiful word is not only our tool, but also our goal. Our goal is a social and public way of life, in which the beautiful word, persuasion, mutual recognition and discussion of human interests, and the idea of interdependence prevail. With our actions, writings, thoughts, and our beliefs in reason, we try to awaken the need for human unity, the need for a more advanced unity than the old ones: the modern, self-disciplining, ‘orderly’ freedom.”

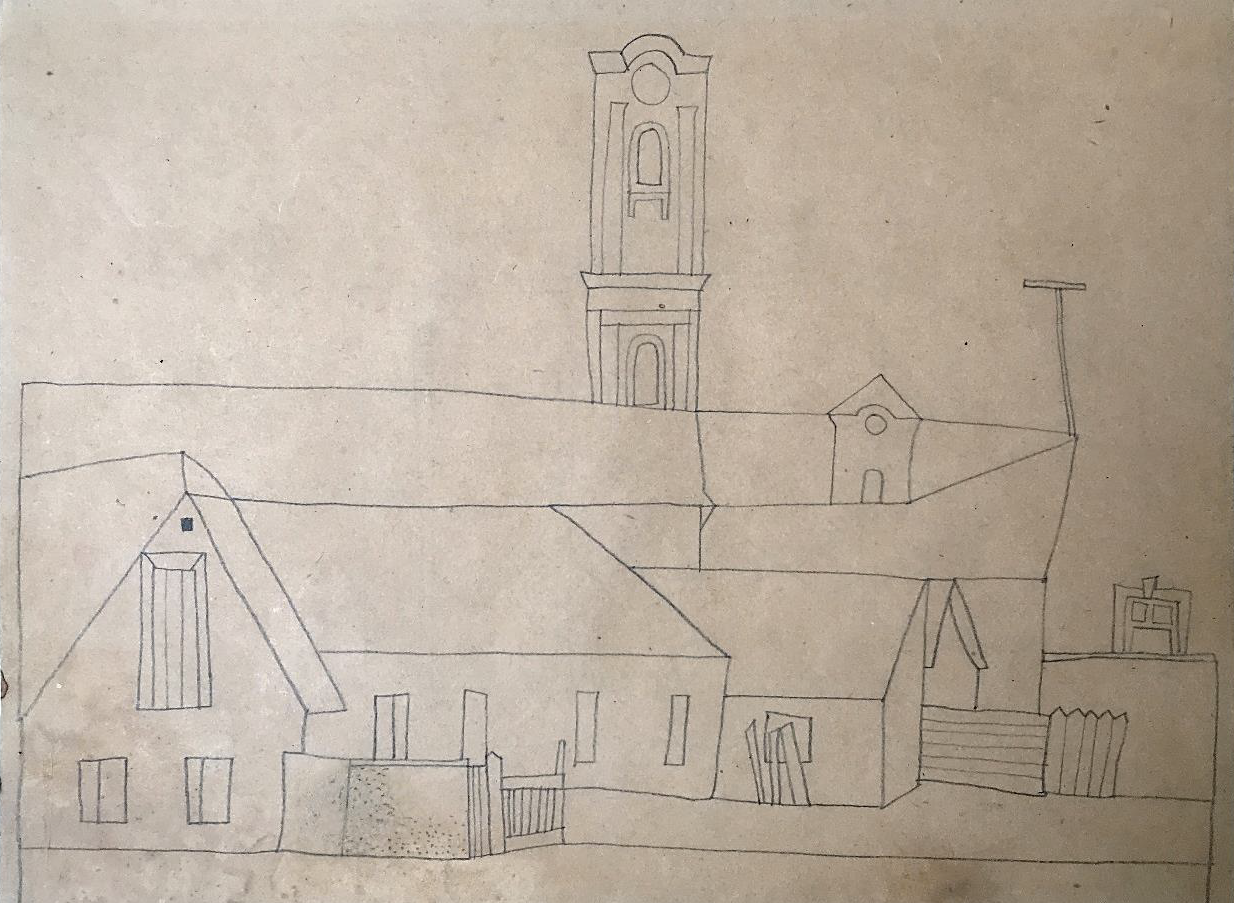

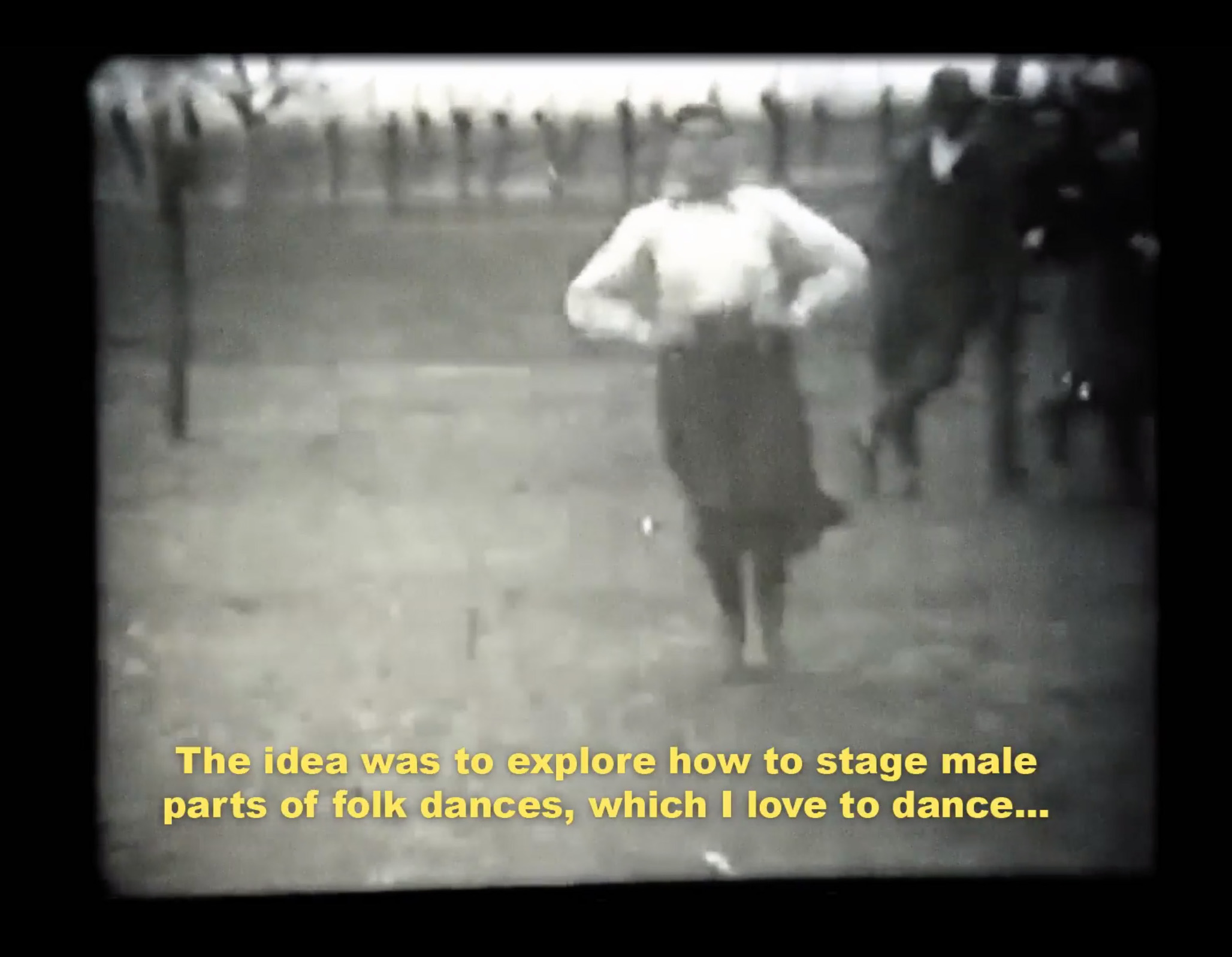

The rural-urban controversy of the 1930s divided the Hungarian intellectual world and it was later revived several times during the 20th century with new characters, new tones and varied intensity. The relationship between rural areas and cities has also been an important issue in various social, political, economic and climate policy discussions in the 21st century. Dominika Trapp has researched transit points of folklore traditions and modernism for a long time. She has interpreted the legacy of Hungarian peasant folk music from a critical perspective with her conceptual orchestra Peasants in Atmosphere, building relations between contemporary artists and a new generation of folk musicians. Her exhibition “Don’t Lay Him on Me” in the Trafó Gallery in 2020 was a reinterpretation of traditional folklore. Trapp and her co-creators turned “towards the archaic in order to find a way out of the crisis of the present” and approached the cultural heritage from a unique “hungarofeminist” perspective related to “hungarofuturism”. She presented her video Maiden’s Dance co-created by folk dancer Kata Szivós and director Noémi Varga that reconsiders the traditionally fixed gender roles in Hungarian folklore, especially in folk dance.

The poem Levegőt! [A Breath of Air!] was published in Attila József’s book of poems titled Nagyon fáj [It Hurts so Much] in early 1936. Although Attila József was already an established poet, it was this volume that brought him real recognition—his new poems were hailed by critics as the beginning of a new phase. For example, one critic wrote: “Few of our new writers have brought so much new value. And yet... I do feel with the acclaimed and popular Attila József, even more than in the case of twenty-year old poets, that I am reading the poems of a poet who, despite his fine past, is still at the beginning of his career, who can bring great surprises, and who, like the age he so honestly and powerfully lives, has not yet found his final balance.” Unfortunately, the critic was not right: the world became more and more out of equilibrium in the years following the publication of the volume, and Attila József also failed to find his spiritual balance. In his last years, his illness became more and more prevalent upon him, and he spent longer periods in a sanatorium. However, he also worked during this period: it was at this time that he wrote his most mature poems, including love poems, or Ars Poetica. But, in his last period, as Miklós Szabolcsi puts it, “In addition to his own hell, Attila József also emerged in the inferno of the age.” Attila József spent his whole life searching for love and the feeling of belonging somewhere with an almost childish stubbornness. When he eventually lost his grip on the world, he felt that life was no longer worth living: ‘What I hold no longer holds me’ (Könnyű emlékek… [Ligh Memories...], 1937). On December 3, 1937, he threw himself in front of a freight train near Balatonszárszó. His last completed, untitled poem, the untitled [Ime hát megleltem hazámat…] [Behold, I found my land…] bears witness to this desperate feeling, but as Szabolcsi put it, “The tragedy of individual existence is not elevated above the tragedy of the existence of others; …even if individual destiny ends in tragedy, it cannot end the same way for humanity.”

(Behold, I have found my land...)

Behold, I have found my land, the country

Where my name's cut without a fault

By him who is to bury me,

If he was bred to dig my vault.

Earth gapes: I drop into the tin,

Since the iron halfpenny,

Which at a time of war came in,

Has outlived its utility.

Nor is the iron ring legal tender.

New world, land, rights: I read each letter.

Our law is war's, the thriftless spender,

And gold coins keep their value better.

Long I had lived with my own heart;

Then others came with many a fuss.

They said: "You kept yourself apart.

We wish you could have been with us."

So did I live in vanity.

I now draw my conclusion thus.

They did but make a fool of me,

And even my death is fatuous.

I have tried all my life to keep

My footing in a whirlwind fast.

The thought is ludicrously cheap

That others' harm matched mine at last.

The spring is good and summer, too,

But autumn better and winter best

For him who finds his last hopes through

Family hearths he knew as guest.

November 24, 1937

Translated by Vernon Watkins