These days any evaluation of the Horthy era, and within that of the Gömbös government, is conducted within an extremely complex interpretive framework fraught with highly charged political and social debates. An unbiased interpretation is—paradoxically—hampered by the historical perspective: the Second World War and the Holocaust, as well as the Soviet occupation and Communist rule in Hungary retroactively shape our conception of this historical period. Many historians and experts try to judge this era based on their own current political affiliation, ideological disposition, temperament, or even events in their own family history. Our knowledge in hindsight thus settles on this era, which, like almost every period in history, had contradictions and uncertainties rather than definite outlines for those who lived through it.

An in-depth study of contemporary sources is therefore important, and this is why contemporary authors who, due to their artistic sensitivity or professional expertise, had a better understanding of all the social and political processes that remained mostly hidden from ordinary people, can play a special role in interpreting the era. Furthermore, it is especially important to critically compare these contemporary sources with each other. In interpreting the Horthy era, these authors should be read side by side, so to speak, “closely”. One such author is Gyula Szekfű, whose book of 1934 Három nemzedék és ami utána következik [Three Generations and What Follows] describes Hungarian society after the Treaty of Trianon, which itself had a significant influence on the ideological atmosphere of the period. In this book, Szekfű, in a much-criticized way, focused primarily on describing the situation of the social elite. Today, Szekfű is seen by many—quite correctly—as an historian who served several political courses. His above-mentioned work is considered by many—also justly—as downright “soul-poisoning” due to its anti-Semitism. But his anamnesis of the “neo-Baroque world” of the Horthy era is very much to the point, as this term provides a particularly impressive critique of the period. With “neo-Baroque” Szekfű defined the nobility-obsessed, authoritarian, deeply hierarchical mentality and political values that were characteristic of the era. According to Szekfű, there was no real mobility in the society of his time; as he writes, “neither the social division nor the social thinking has changed much; and everything in this field has remained as people were accustomed to during the third generation”.

The Horthy regime remained essentially unchanged during a period of constant—economic, political and social—change. Gömbös and his government started out in the spirit of change and won over the masses with their ostentatious reform policy. However, in addition to the economic successes, it is also worth noting the voices that call attention to the restrictive-repressive features of the regime. In assessing Gömbös’s achievements as Prime Minister, in addition to monitoring macroeconomic data and the development of external relations, it is therefore worthwhile to draw on these sources. It is instructive, for example, how similarly the conservative, “bourgeois” writer, Sándor Márai and the left-wing poet, Attila József described the “filing” practice of the Gömbös government: how the governing party (the National Unity Party, NEP) collected data on voters.

Gyula Gömbös and Miklós Horthy, 1935

bw. photo, exhibition print

Hungarian National Museum – Historical Photo Department, Budapest, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Szabó I. Jr., Magyar Nép Hete – Szenzációs riportkiállítás az Iparcsarnokban [Week of the Hungarian People, Sensational reportage exhibition at the Industry Hall], October 2–11, 1936

lithography, exhibition print

Budapest Poster Gallery

Company in goggles for quartz lamps, 1925

bw. photo, exhibition print

Fortepan / Ákos Lőrinczi

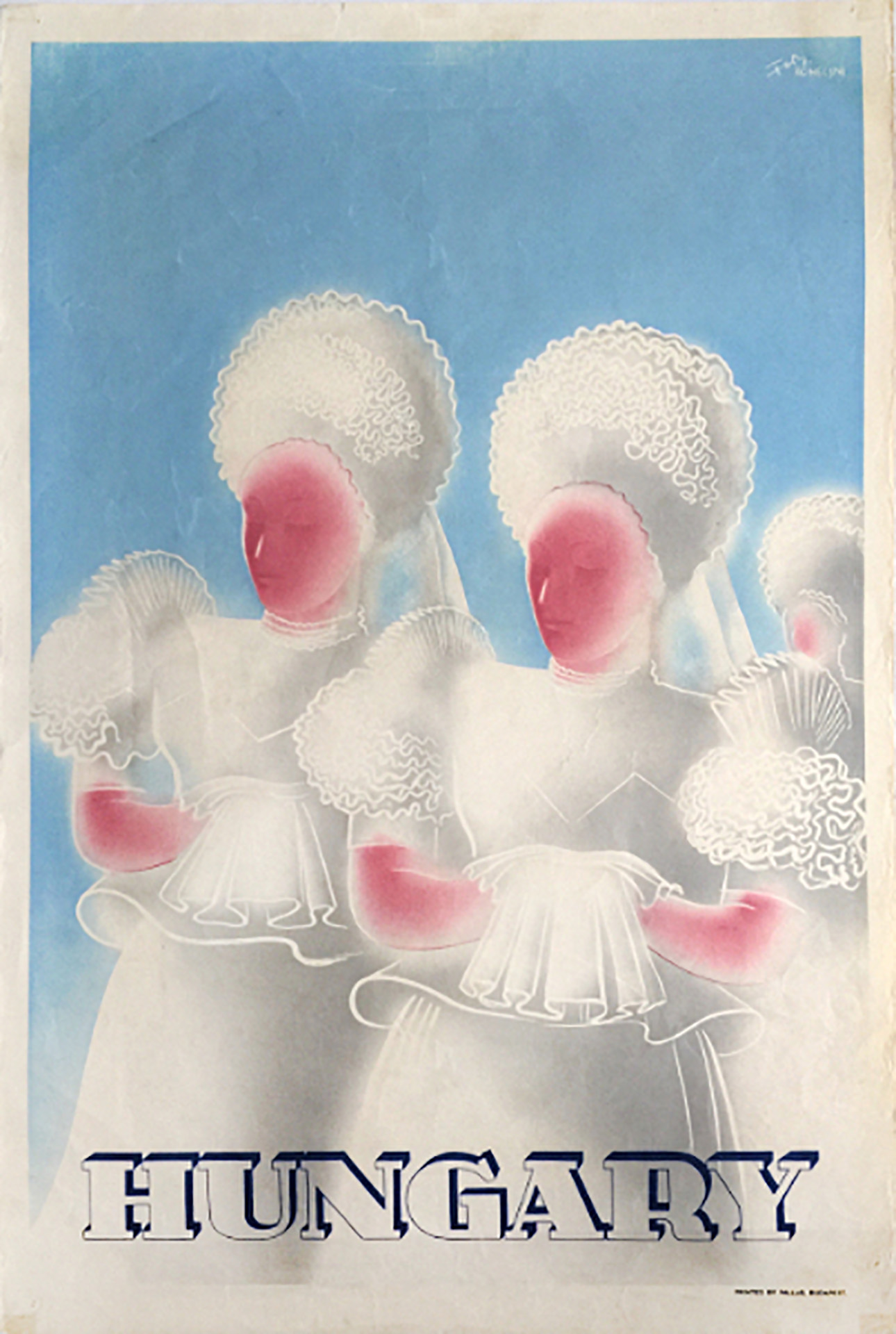

Konecsni György, Fery Antal: Hungary, 1936

lithography, exhibition print

Budapest Poster Gallery

Vice-Admiral “Vitéz” Miklós Horthy de Nagybánya served as Regent of the Kingdom of Hungary from March 1, 1920 until October 16, 1944. During this period of nearly 25 years, Hungary was an authoritarian democracy with a functioning multi-party parliament, though with significant restrictions on civil liberties and political pluralism—this is what we would now call a “hybrid regime”. The main objectives of the governments functioning under Horthy’s regency were: in domestic terms, to strengthen the neo-feudal Christian-nationalist foundations of the Hungarian state and contain the spread of Bolshevism; and, in external terms, to regain territories that Hungary lost under the terms of the Treaty of Trianon signed in June 1920. Hungary allied itself with the Axis powers in order to achieve the latter objective in the 1930s. As head of state of the Kingdom of Hungary, Miklós Horthy did not participate directly in the legislative and executive processes of the National Assembly / House of Representatives and the government. However, Horthy did exercise considerable political authority through the powers invested in him as regent. These powers underwent gradual expansion in the 1930s. The Regent was empowered with the following prerogatives the year he came to power in 1920: these included; the right to appoint the prime minister; the right to approve or reject legislation that the government intended to submit to the National Assembly; and the right to suspend the activity of the National Assembly for up to 30 days. In 1933, the House of Representatives approved a law investing the Regent with authority to suspend the operations of the legislature for an indefinite period of time and to dissolve the body at his discretion. Regent Horthy, however, rarely invoked these prerogatives during his 24 years as head of state. His power remained mainly symbolic, and Horthy himself became a symbolic figure. The Horthy-cult consisted of several images of the Regent: he was primarily depicted as the “savior of the nation”, who, as the Head of the National Army had rebuilt the country from its ruins after the short-lived Soviet Republic in 1919 and the Romanian occupation. Later another layer was added to this image: that of the Regent who governs the country taking it to prosperity. And, finally, after the first and second Vienna Awards (in 1938 and 1940), Horthy’s cult was extended with the image of the “nation-builder”, who managed to right the wrongs of the Treaty of Trianon, with the return of a part of Transylvania and the Partium from Romania, as well as the Magyar-populated territories in southern Czechoslovakia to Hungary. Horthy’s cult also represented the “royal” aspect of the Hungarian Kingdom, which was a country without a king. (The former Habsburg kings had been dethroned in accordance with the Treaty of Versailles). Horthy’s image was omnipresent (replacing the image of the Habsburg rulers), and his name-day (the celebration of one’s guardian saint) was made into a national holiday. And just as the districts and bridges of Budapest had in the past been named after the members of the Habsburg family, the newly-built bridge (today’s Petőfi Bridge) on the Danube was named after Horthy.

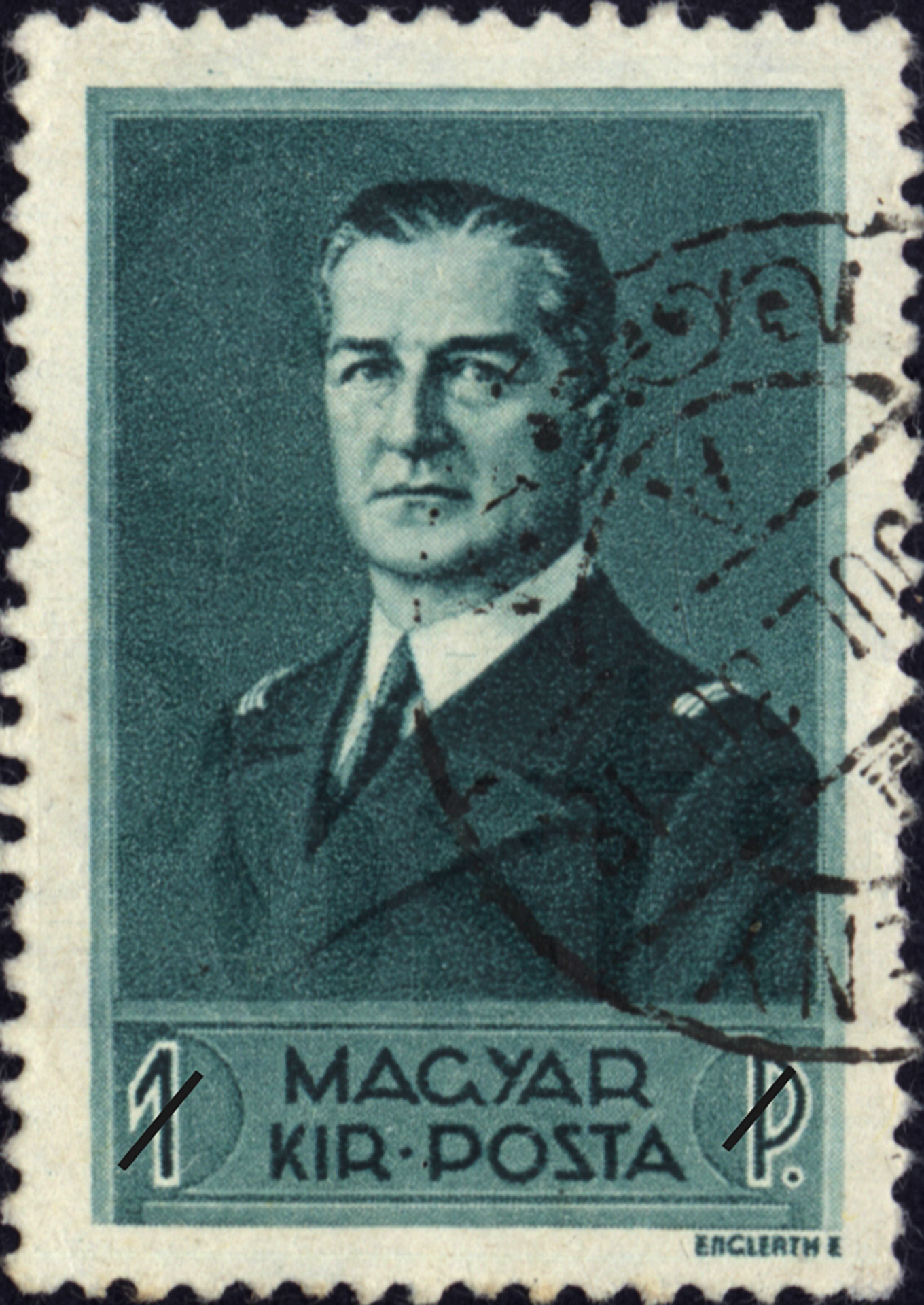

Regent Miklós Horthy on the stamp of the Hungarian Royal Post (Regent’s portrait series I), 1930s

design by Emil Englerth

postage stamp, exhibition print

National Széchenyi Library, Budapest / DKA

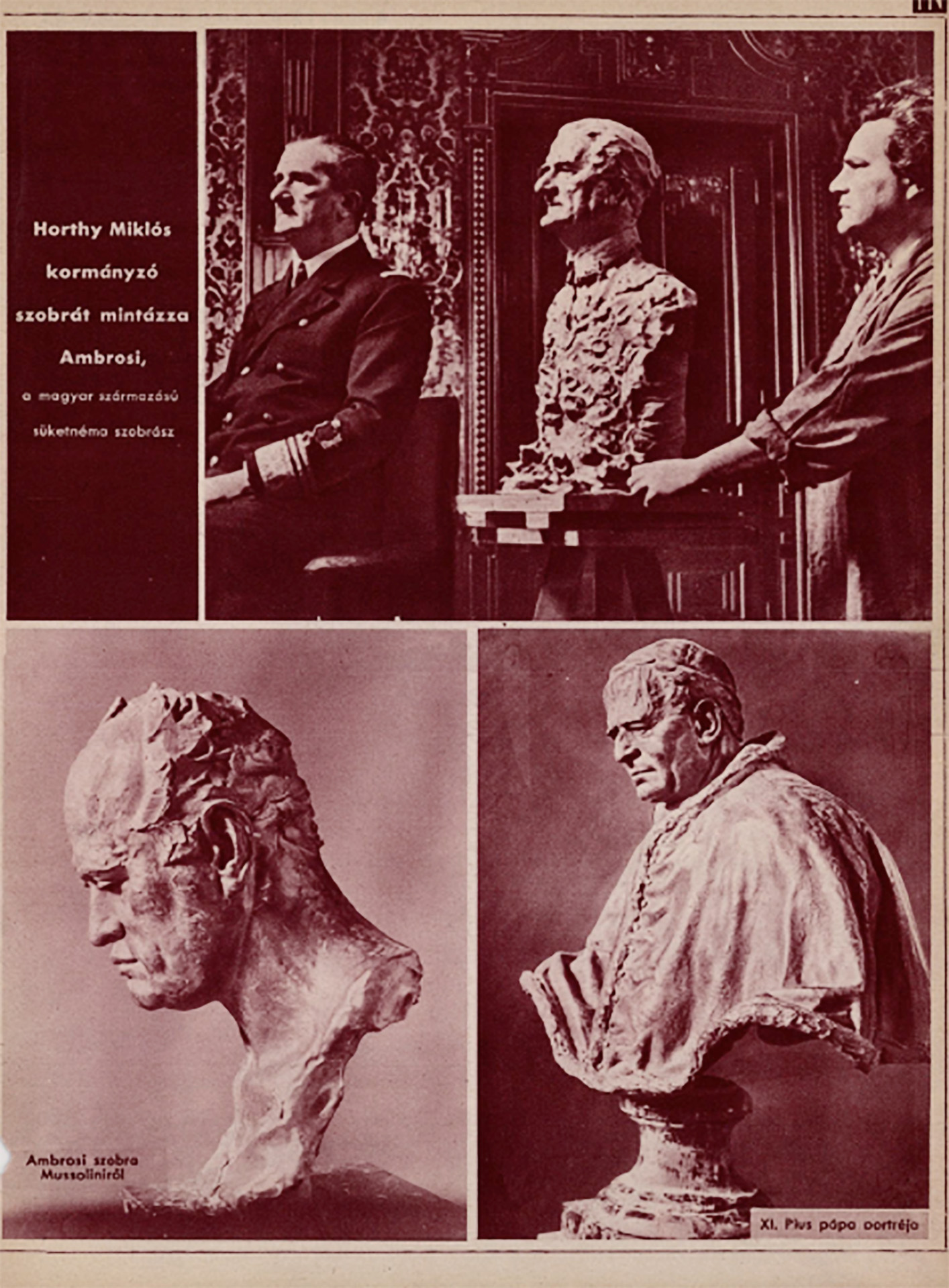

“The statue of Regent Miklós Horthy was modeled by Ambrosi, a deaf-mute sculptor of Hungarian origin (Below: the bust of Mussolini and of Pope Pius XI, also by Ambrosi), 1934

exhibition print

Pesti Napló Képes Melléklete [Illustrated Supplement of Pesti Napló], February 25, 1934 / Arcanum

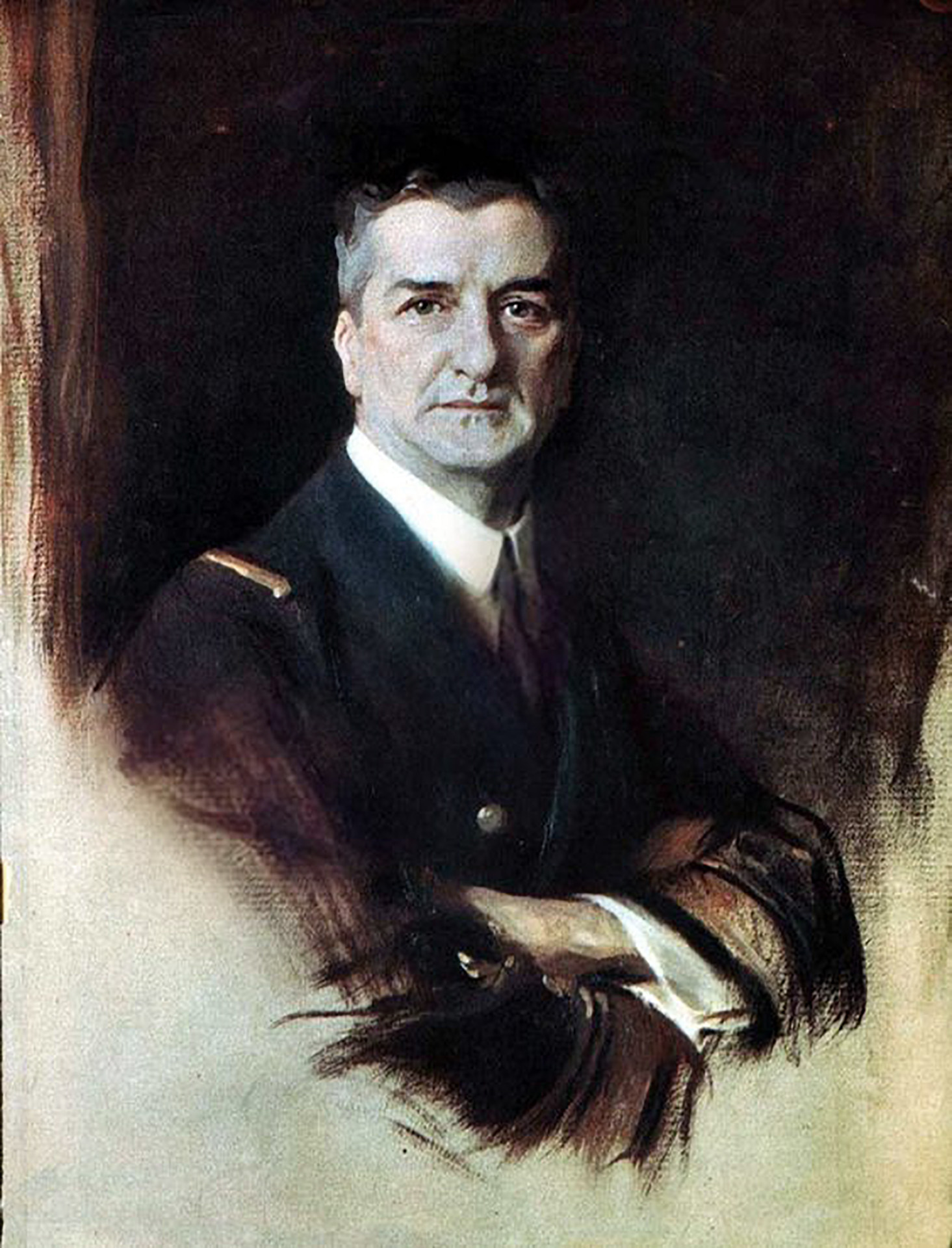

Fülöp Elek László, Portrait of Miklós Horthy, 1927

oil on canvas, exhibition print

©The de Laszlo archive Trust

Vilmos Aba-Novák: Hősök Kapuja (Porta Heroum) [Gate of Heroes], Szeged, 1936–1937

detail: Horthy, “Hungarians! Our heroes’ sacrificial blood obliges us!“

fresco, reproduction (photo by János Kozma)

wikimedia commons

Miklós Horthy Bridge (today Petőfi Bridge), 1933–1937

bw. photo, exhibition print

National Széchenyi Library, Budapest / DKA

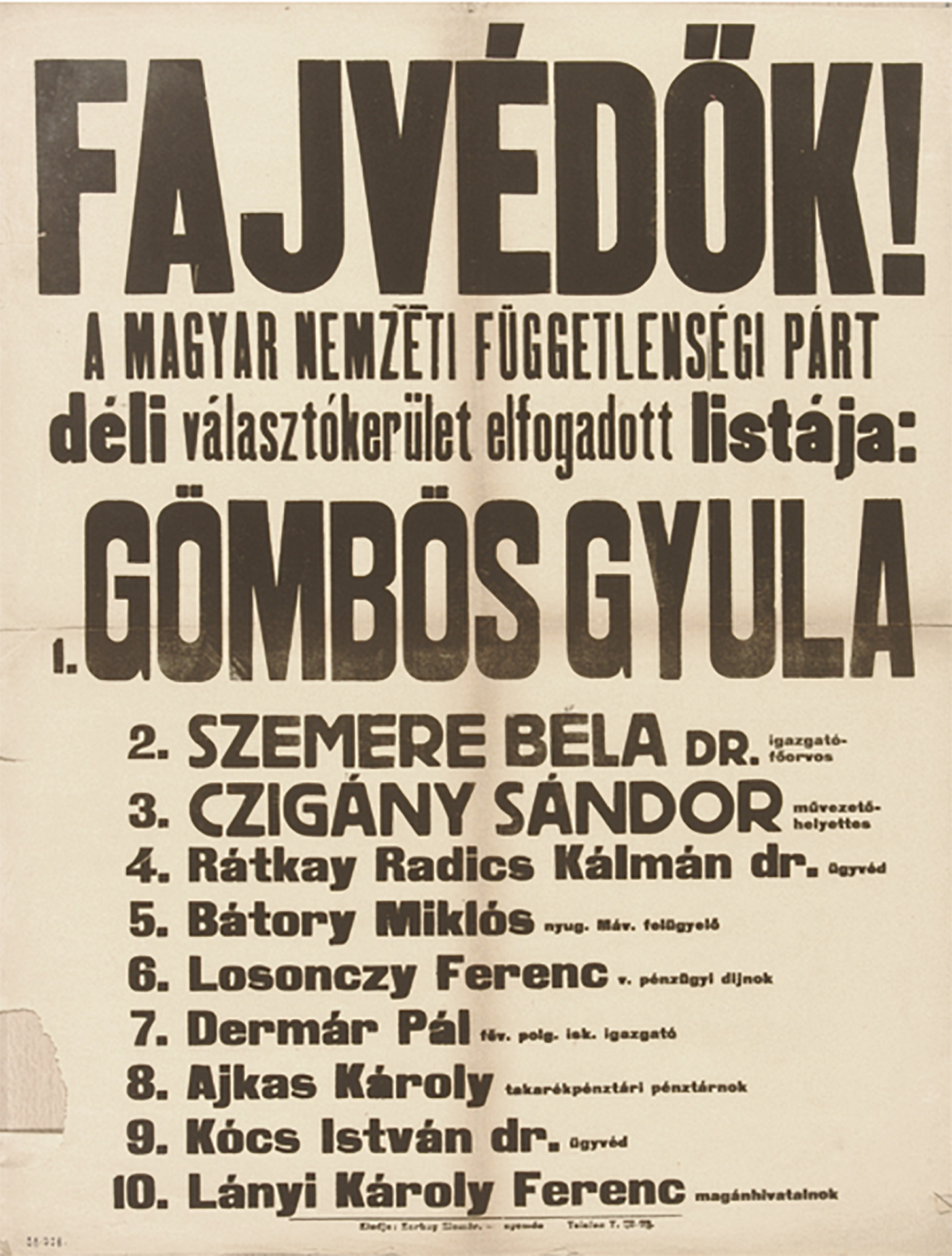

Gyula Gömbös, former staff officer and honorary general received his mandate as prime minister from Regent Miklós Horthy on October 1, 1932, at the height of the Great Depression. Gömbös was no newcomer to Hungarian politics. He had entered the political arena in January 1919, when he established the Magyar Országos Véderő Egylet [MOVE, Hungarian National Defense Association], a paramilitary organization based on the notions of racial defense. After the collapse of the Hungarian Soviet Republic in the Summer of 1919, he took part in the organization of the future “eternal” governmental party, the Egységes Párt [Unity Party], on the side of István Bethlen, the president of the party and Premier of Hungary between 1921 and 1931. In the 1920s, he established the extreme right Racial Defense Party, an opposition force. But as this enterprise did not take off he dissolved it and returned to the governmental party, for which he was awarded with top administrative positions. In 1932, before he assumed Premiership, he was Minister of Defense in the failed Gyula Károlyi government.

Gömbös took his new mandate with ambitious plans and with the conditional support of István Bethlen, who remained the effective leader of the governmental faction, and whose reputation still remained unchallenged. Gömbös’ principals, Bethlen and Horthy believed that Gömbös, on the basis of his political past and with his daring reform ideas, might be able to pacify and integrate those social groups and political movements—the growing camp of the extreme right, the disillusioned workers, the farmers whom the economic crisis had thrown into a critical situation, and the poorer peasantry—whose disaffection and rebellious sentiments had already threatened the stability of the system. As Gömbös put it in one of his speeches in 1932: “If I integrate the Hungarian workers into the society of the nation, the Socialists will not have a place in politics in Hungary anymore.”

He outlined his reform plans in his Nemzeti Munkaterv [National Work Plan] that consisted of 95 clauses, with the key motive at its focus, “national autotelicness” [“nemzeti öncélúság”, “self-sustaining”]. Besides the measures of economic stabilization, it envisaged social reforms aiming at a fairer distribution of wealth between the grand capital and the working class, the farmers, peasants and landlords. Its proposed institutional construction followed the model of the corporative system of Mussolini’s Fascist state. The most important slogans of his agenda were: the brotherhood of capitalists and workers, the unification of farmers and landlords, the tearing down of the walls between the social classes, and relieving the injustices of capitalism while still preserving respect for private property. However, his integrational aspirations were highly controversial since, instead of extending democratic political rights and institutions, he planned to achieve these goals by the centralization of state power, and the further reinforcement of the autocratic character of governance, the curtailment of traditional municipal rights and powers as well as by constraining a unified “Hungarian” worldview and public opinion.

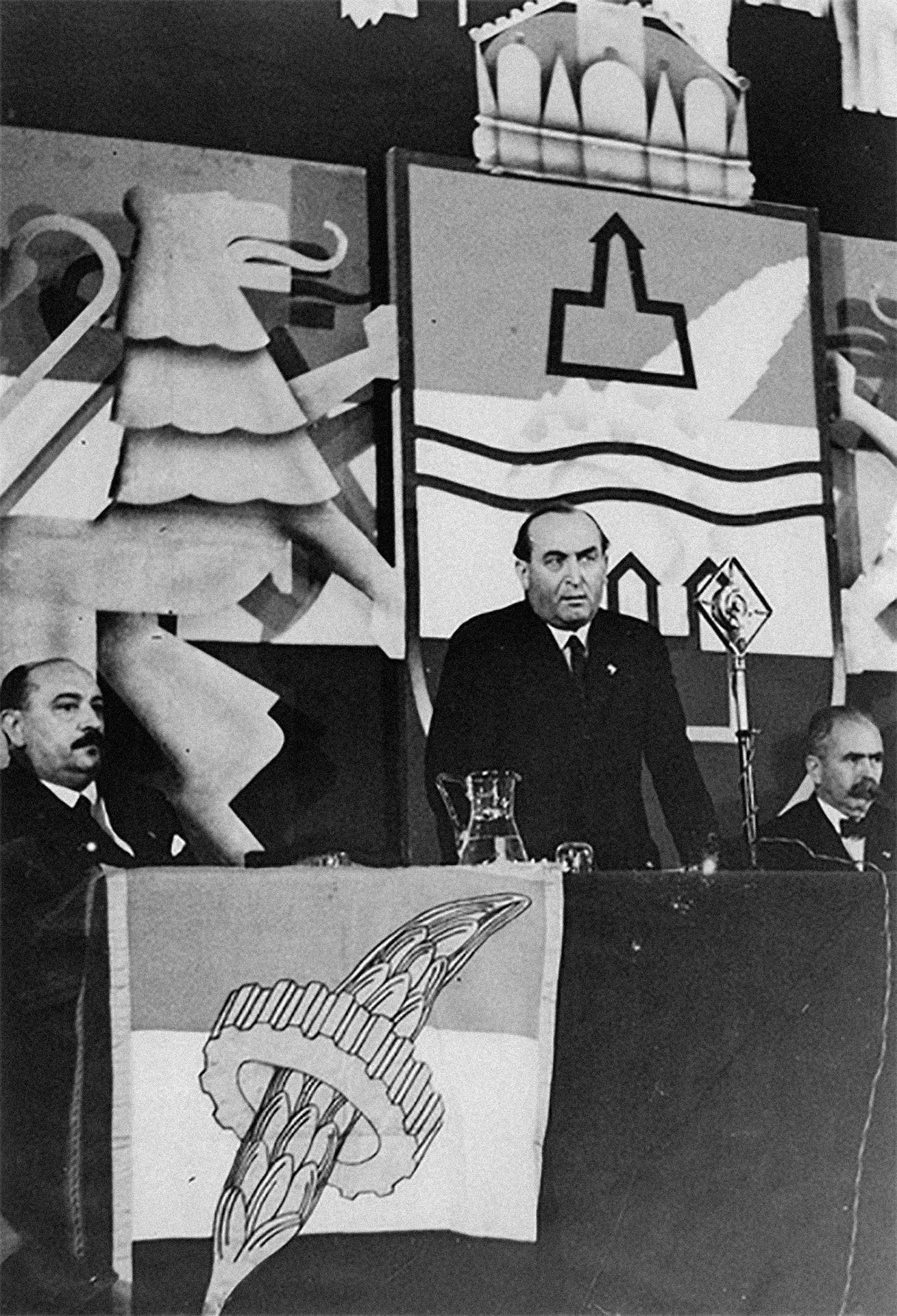

From his reform initiatives Gömbös also expected to construe and expand his own, independent political basis by involving social groups that had previously remained outside of politics. One of his first moves in 1932 was the reorganization of the governmental party under a new name, the Nemzeti Egység Pártja [NEP, Party of National Unity], and to shape it according to his own interests and preferences.

The foreign policy of the Gömbös government tried to consolidate the already existing good relations with Mussolini’s Italy, the model of his political desires, and open up new channels to the Austro-Fascist dictatorship of chancellor Dollfuß in Austria, and towards Germany after Hitler came to power. The corroboration of German contacts were not primarily vital for ideological reasons. The motivations were rather based on the common interest to revise the Treaties of Versailles, and the opening of the German (agricultural) market to Hungarian commodities. These foreign policy maneuverings were not unproblematic, since in those times Italy and the German Reich were to a certain extent still rivals on the international scene. German aspirations for the annexation of Austria (Anschluss) were widely known, while Gömbös had always been a firm proponent of an independent Austria. Still, undoubtedly, that was the period when Hungarian foreign policy, after the attempts at British orientation throughout the 1920s, and after a short and aborted endeavor of French orientation in 1931, gradually, but definitively turned towards the future Axis powers, Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy.

His ostentatious reform ideas were initially received with broad enthusiasm. His measures regarding economic stabilization, partly due to increasing international prosperity, were not unsuccessful. The financial support for the indebted farmers and landlords and the opening up of agricultural markets relieved the agricultural sector, while the protectionist industrial policy facilitated the faster recovery of industrial enterprises. The unemployment rate decreased. However, these achievements came at a price: salaries and incomes stagnated while taxes were raised. The land reform remained unfeasible. Instead of meaningful progress and changes in social relations, the only things that remained were the centralizing efforts of state power, growing authoritarian tendencies, further cuts in political rights and an arrogant nationalistic rhetoric.

The general disappointment can be best described by the contemporary accounts of a meeting between Gömbös and the prominent representatives of the so-called népi [“populist” or “folk”] writers that took place in April 1935 in the villa of the highly esteemed writer, Lajos Zilahy. When Zsigmond Móricz arrived at the gathering he read out the weekly diet of a poor peasant family, which he had recorded on the back of a menu card from the elegant Hotel Ritz. The shocked Prime Minister could only react by saying: “Zsiga, I heard bad things about you, you are destructive.” Then Gömbös turned to Gyula Illyés and asked him: “What would you do in this situation, if you were the governor of Hungary?” The answer was:

“I would hang all the great land-owner vicomtes and the Catholic bishops at once!”

Although the governmental party won a resounding victory at the general election of 1935, the election procedure was tainted with scandalous manipulations and the violence meted out by the gendarmerie, which further eroded the legitimacy and credibility of the Gömbös-government. However, his reign was not shaken by the election frauds or the general disappointment for his unfulfilled promises. His superiors of the political elite, with Bethlen and Horthy at the head, concluded, that his envisaged centralized and corporative state might put their hegemony and the balance of the political system established in 1919 into jeopardy. In January 1936, Gömbös was already a fallen politician. The only reason why he had not been replaced was his lingering kidney failure that led to his death on October 6, 1936.

Tibor Pólya, Gyula Gömbös, c. 1935

oil, canvas, exhibition print

Hungarian National Museum – TK Painting Collection, Budapest

The Gömbös Government after the official swearing-in: Ferenc Keresztes-Fischer, Gyula Gömbös, Endre Puky, Miklós Kállay, Andor Lázár, Bálint Hóman, Béla Imrédy, Tihamér Fabinyi, István Bárczy Bárczy, 1932

bw. photo, exhibition print

Hungarian National Museum – Historical Photo Department, Budapest, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

“Race Defenders! The list of the Southern Constituency of the Hungarian National Independence Party”, 1920

bw. photo, exhibition print

Hungarian National Museum – Historical Photo Department, Budapest, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

After the resignation of the Cabinet, the Regent appointed the second Gömbös government

Magyar Világhíradó 576. February 1935

Hungarian, with English subtitles, 0’59”

Hungarian National Film Fund

István Bethlen and Gyula Gömbös travel to Debrecen, c. 1932

bw. photo, exhibition print

Hungarian National Museum – Historical Photo Department, Budapest, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Gyula Gömbös, Bálint Hóman and Tivadar Zsitvay at the meeting of the National Work Center [Nemzeti Munkaközpont], 1933–1934

bw. photo, exhibition print

Hungarian National Museum – Historical Photo Department, Budapest, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

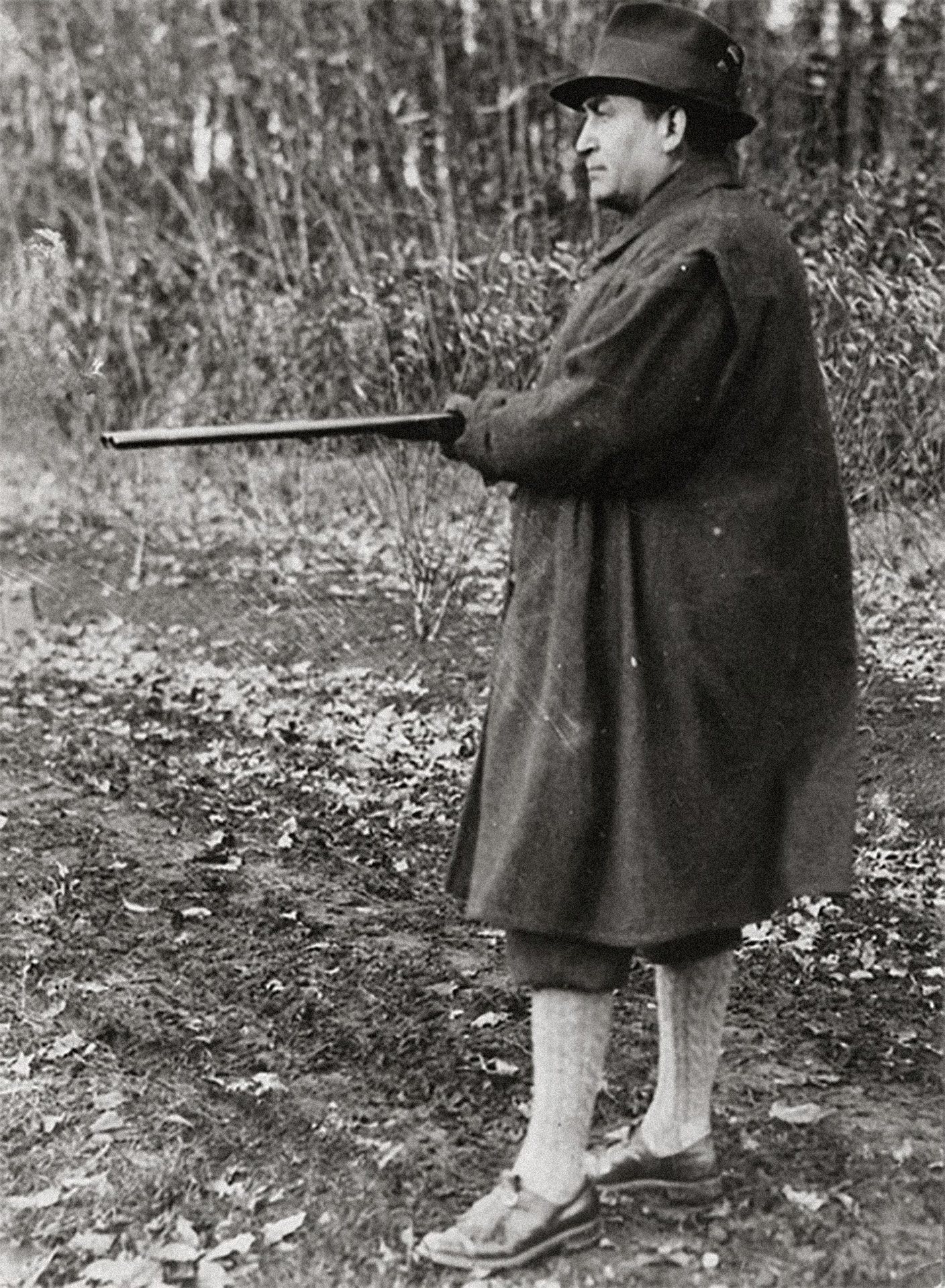

Prime Minister Gyula Gömbös on a hunt, c. 1935

bw. photo, exhibition print

Hungarian National Museum – Historical Photo Department, Budapest, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Benito Mussolini, Engelbert Dollfuß and Gyula Gömbös sign the trilateral Rome Protocols at the Palazzo Venezia, Rome, 1934

bw. photo, exhibition print

Hungarian National Museum – Historical Photo Department, Budapest, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Dollfuß, Mussolini and Gömbös in Rome, 1934

exhibition print

Pesti Napló Képes Melléklete [Illustrated Supplement of Pesti Napló], March 18, 1934 / Arcanum

Hermann Goring (then Prussian prime minister) and his wife arrive on a two-day visit to Budapest on their way to the Adriatic Sea. Mátyásföld Airport, May 25, 1935

bw. photo, exhibition print

Fortepan / Hungarian Technical and Transport Museum / Archives / Negative Collections / Hungarian National Museum – Historical Photo Department

Gyula Gömbös with Benito Mussolini, 1936

bw. photo, exhibition print

Hungarian National Museum – Historical Photo Department, Budapest, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

The funeral of the Prime Minister Gyula Gömbös: after the farewell, the mourning procession began in Lajos Kossuth Square, on the steps of the Parliament building, October 10, 1936

bw. photo, exhibition print

Fortepan / Sándor Bojár

Prime Minister Göring, Foreign Minister Ciano, Chancellor Schuschnigg at the funeral of Prime Minister Gyula Gömbös in Kerepesi Cemetery, October 10, 1936.

bw. photo, exhibition print

Hungarian National Museum – Historical Photo Department, Budapest, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

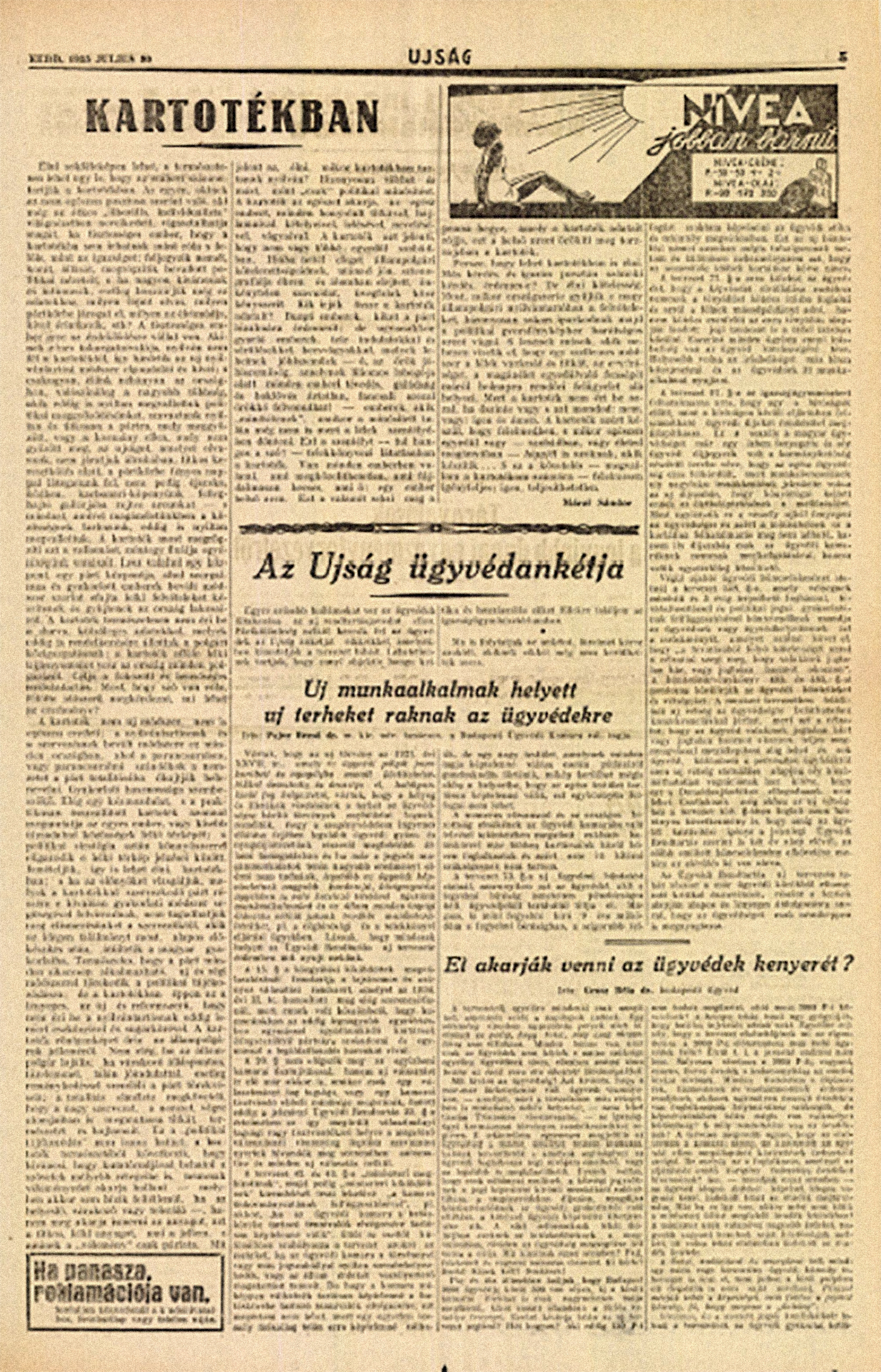

The daily newspaper Újság published an article titled “In Files” on July 30, 1935. Its author was writer Sándor Márai, who, like Attila József, harshly criticized the Party of National Unity’s [NEP] registration system, the infamous “files.” Márai, who, according to his own admission, “grew up in the damned ‘liberal, individualist ’worldview”, found this practice unacceptable, according to which the NEP’s organizational department collected data on all the voters of the country. As can be gleaned from the documents of the NEP: “Each of the country’s 3,339 municipalities, 40 counties and 11 jurisdictions has one archive, in which all the data and reports on the municipalities are stored.” These record centers also handled copies of personal files completed for each voter by the local party organizations, as well as the declarations of allegiance of the leaders appointed by Gömbös. The organizational department paid special attention to the tasks related to the elections: voter registers, results, legislative changes, etc. István Antal, one of Gömbös’ most confidential employees, and the head of the press department of the Prime Minister’s Office, described the records center in his later recollections with contempt: at the party headquarters, “two or three rooms were filled with files and records of various levels, and twenty or twenty-five new party officials hunched, typed, counted, scribbled, and telephoned in front of the two dozen desks,” he wrote. “A separate room had to be rented for the storage of cards and files, and there was the danger that this sea of files would flood Esterházy Street, washing away the party with its general secretary […] together with the party bureaucracy.” Many writers and journalists protested against this industrial-scale data collection in the opposition press. The “bourgeois” writer Márai made quite similar objections to Attila József: “Now that records are being collected for this large civil registry across the country, surely many will try to put on a friendly face for political snapshots. And there will be others who will find it hard to bear that a witty method puts the charm and secret of the soul, the individuality, the unique majesty of privacy, under police surveillance from one day to the next. Because for the file it is not enough if you are honest and say no, or: yes and amen. The file is created so that when you are all alone, in fear—in your room or in the solitude of your life—you can also believe those who create it ... And this proposition—I confess to my files—is terribly demanding; indeed, it is unachievable. "

Sándor Márai, Kartotékban [In Files], 1935

exhibition print

Újság, July 30, 1935 / Arcanum

Gömbös’ party, the Nemzeti Egység Pártja [National Party of Unity, NEP] (and its direct predecessors) had been in power since its foundation in 1922 in the National Assembly/House of Representatives of Hungary. Its main rival was the Magyarországi Szociáldemokrata Párt, [MSZDP, Hungarian Social Democratic Party], which was the main opposition party in the National Assembly from 1922 until 1935. According to the Bethlen–Peyer Pact of December of 1921, the government would permit the Hungarian Social Democratic Party to function legally under the protection of the law and to establish trade unions, while the MSZDP would refrain from conducting labor-organization among employees of the state, notably railway and post-office workers. The conservative-agrarian Független Kisgazda-, Földmunkás- és Polgári Párt [FKgP, Independent Smallholders, Agrarian Workers and Civic Party] became the largest opposition party during the elections of 1935. Communist political activity was banned in Hungary throughout the interwar period pursuant to the “Order Law” [rendtörvény] of 1921. In the mid-1930s, the first Hungarian National-Socialist parties were also formed. During the elections of 1935, Gömbös’ party went to great lengths to secure its victory. The NEP could rely on the carefully collected data [“files”] on voters, and on additional privileges they gained as the governing party: huge amounts of campaign money, the monopolization of Hungarian Radio as a propaganda tool, and the constant changes in the electoral legislation. Nor did the party shy away from election fraud: the rejection of opposition recommendation sheets, the direct influence of voters, which was particularly drastic in the rural areas (casting ballots privately were only held in Budapest and its agglomeration, as well as in larger cities), where violence by the gendarmerie was also used for persuasion. The most serious case took place in Tarpa, where Gömbös elected a person as a representative standing against the joint candidate of the opposition parties, Endre Bajcsy-Zsilinszky (a former ally who did not want to join him), who later turned out to not only have a false name, but not to even have the right to vote. (József Attila’s poem “A Breath of Air!” was partly written as a reference to this case). After the elections, a total of 38 seats were petitioned, and the results were annulled by the Administrative Court in 17 of these cases. Nevertheless, it cannot be ruled out that Gömbös would have won a majority in a “clean” election, due to his relative popularity and the success of his reform rhetoric.

Endre Bajcsy-Zsilinszky, c. 1930

bw. photo, exhibition print

Hungarian National Museum – Collection of Portrait Photographs, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

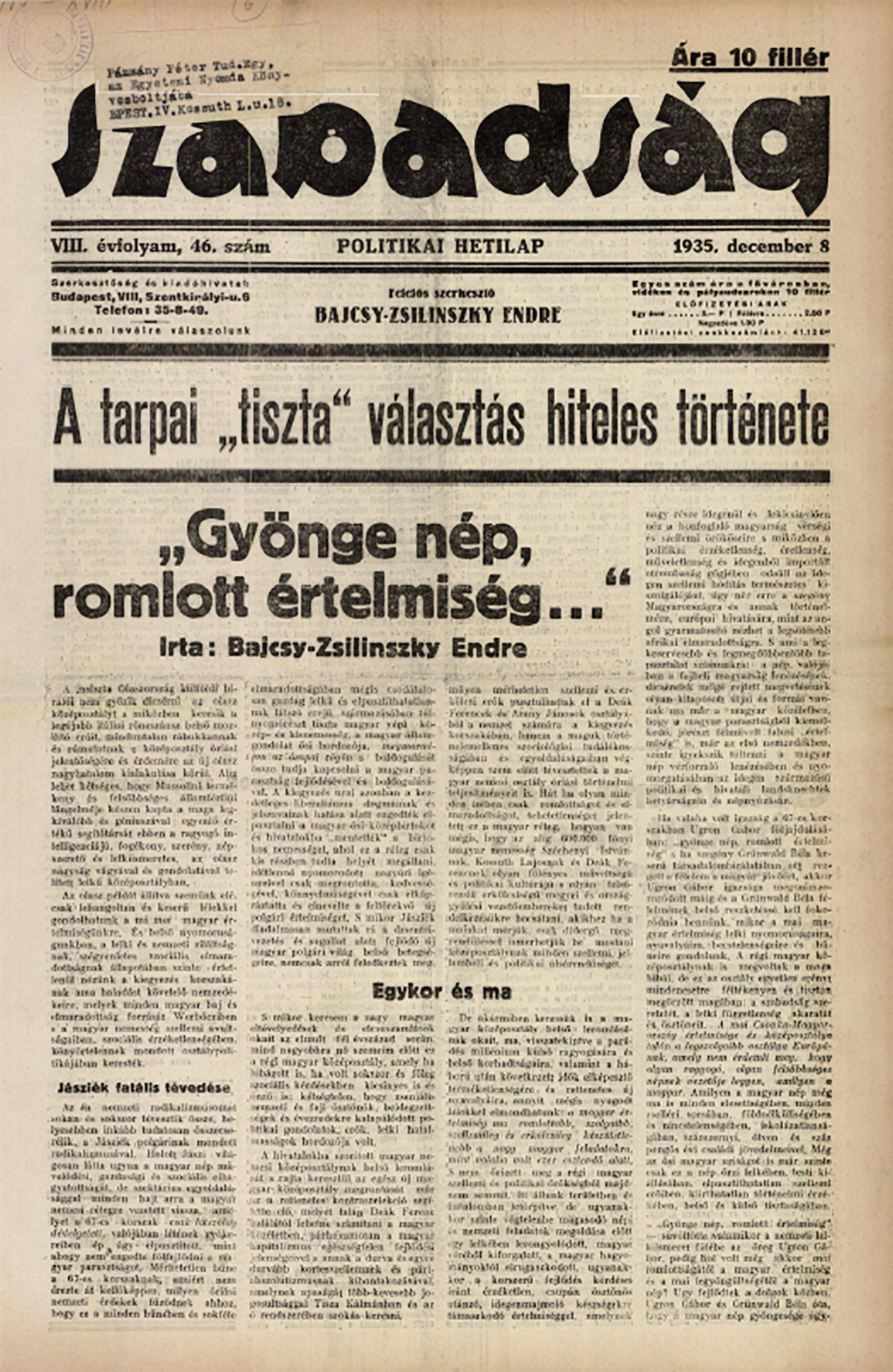

Endre Bajcsy-Zsilinszky, „A tarpai ‘tiszta’ választás hiteles története. Gyöngye nép, romlott értelmiség…”, [An authentic story of Tarpa’s ‘clean’ election. Weak people, depraved intellectuals…], Report of the weekly, Szabadság (which was edited by Bajcsy-Zsilinszky himself) on the Tarpa election, December 8, 1935

kiállítási nyomat

Szabadság [Freedom], December 8, 1935/ Arcanum

The central element of Gömbös’s press policy was the “theory” of propaganda and the power of the press, and he strongly emphasized the importance of controlling public opinion through propaganda. This included banning certain newspapers while protecting others. A conservative MP referred to this press policy in 1934 with the statement: “There is a governmental press dictatorship in Hungary”. The Prime Minister also encouraged the establishment of government-adjacent media. As a result, Pesti Ujság, among others, was established. Hungarian Radio was also considered and used as an effective propaganda tool. Thanks to its founder, Miklós Kozma (who was Minister of the Interior from 1935 to 1937), Hungarian Radio underwent incredible development in the 1930s. Many cultural programs were broadcast, including numerous literary performances; Attila József also appeared several times in the literary programs of Hungarian Radio (which were edited by László Cs. Szabó). Nevertheless, the majority of Hungarian Radio’s programs consisted of music, and in the “world of jazz madness”, the editors preferred Hungarian songs [nóták] and “Gypsy” music that were more in line with official Hungarian politics. The news programs were edited according to the government’s wishes. Yet, radio propaganda could only affect the upper half of society: by the end of the decade, Hungarian Radio only had about 500,000 subscribers.

Bálint Hóman, Gyula Gömbös, Miklós Kozma, 1936

bw. photo, exhibition print

Hungarian National Museum – Historical Photo Department, Budapest, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Gyula Gömbös, Gyula Somogyváry and Tihamér Fabinyi in the Hungarian Radio building, 1935

bw. photo, exhibition print

Hungarian National Museum – Historical Photo Department, Budapest, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Women listening to the radio, 1935

bw. photo, exhibition print

Fortepan / Kálmán Szöllőssy

“Népszava” Calendar (design by Károly Dukai, 1935

book (paper, letterpress)

Budapest Poster Gallery

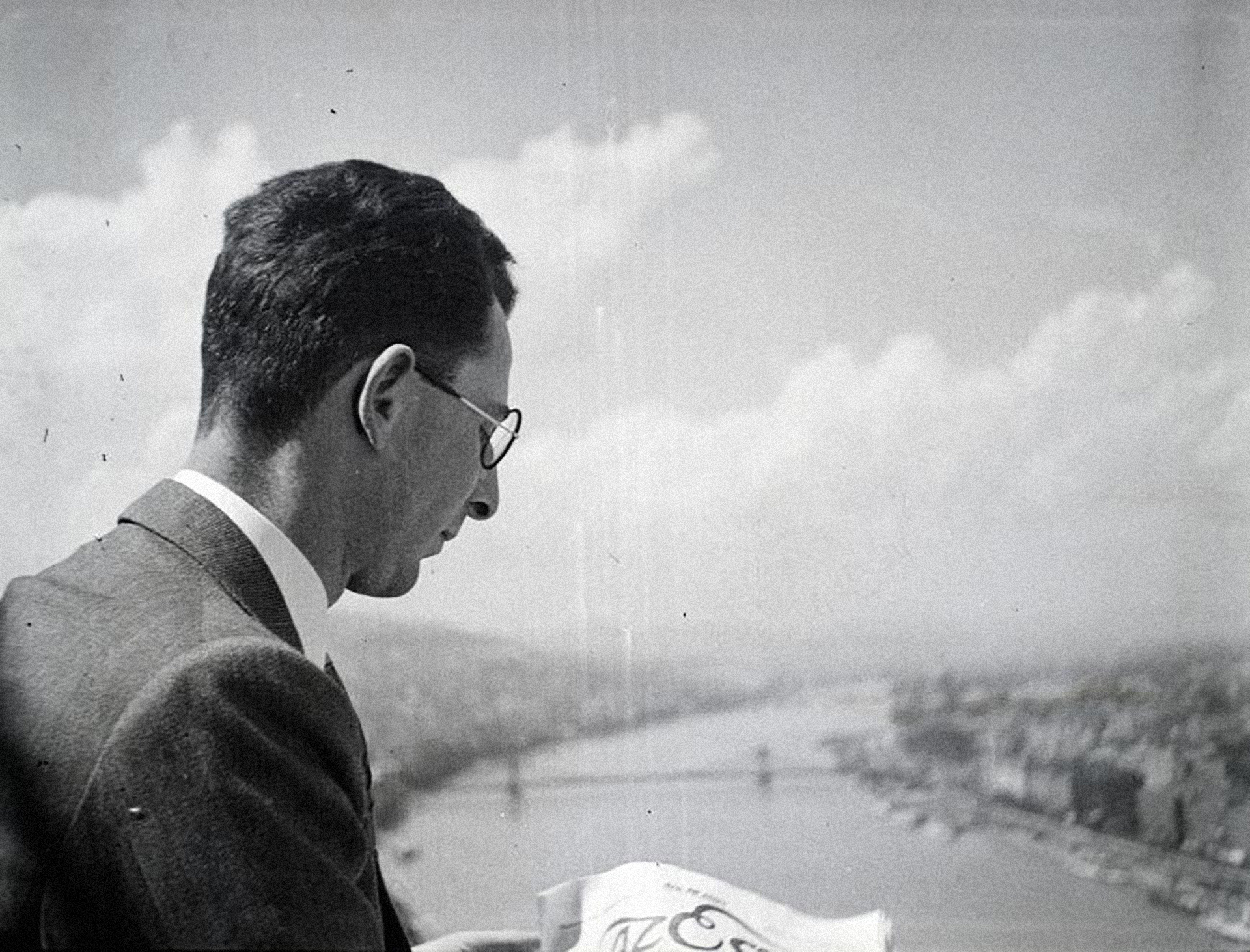

Man (Ákos Feuer) reading the daily newspaper Est [Evening], 1935

bw. photo, exhibition print

Fortepan / Ákos Lőrinczi

The Turul* Association was the largest university student organization in Hungary between 1919 and 1945. In the second half of the 1930s, the association had 40,000 members. Throughout its existence, its main political character was mostly determined by far-right political ideas, racial defense and anti-Semitism with a strong commitment to social solidarity. In the 1920s and 1930s, the political views of its mainstream were closest to the ideas of Gyula Gömbös—Premier of Hungary between 1932 and 1936—but, in some critical respects the association always remained loyal to Regent Horthy and the post-1919 political regime. In 1921, when King Charles IV, who had abdicated, tried to retake his Hungarian throne, the armed battalions recruited from the ranks of the Turul Association took part in the defense of Horthy’s rule.

In the early 1920s, the association’s activities primarily focused on the restriction of the admission of “Jewish” students to university courses. They demanded even more extreme limitations than those stipulated in the law, numerus clausus, which was passed by Parliament in 1920, and which prescribed strict quotas for students of Jewish origin. At the beginning of the 1920s, the participants and organizers of the so-called “Jew-beatings” and other anti-Semitic atrocities on university campuses were mostly members and activists of the Turul Association. In the early 1930s the alleviation of certain elements of the law in the numerus clausus and the miseries caused by the Great Depression radicalized the Turul membership. In 1932–33, the anti-Jewish atrocities on the campuses of the universities of Debrecen, Szeged and Budapest became more frequent again. The situation was so scandalous that even Bálint Hóman, Minister of Culture and Education, who was well-known for his extreme right-wing views, voiced his concern about them in Parliament.

Throughout the 1930s, the Turul Association amplified its activities in the area of student welfare and benefits, in order to facilitate the admission of students who came from the lower and poorer ranks of society, and ran an extensive institutional network to support these efforts. From the mid-1930s, the political orientation of its membership gradually changed through the large numbers of new members who cherished far-left, left-populist or far-right views and sentiments. The new wave caused increasing tensions within the local organizations of the Turul Association and led to the splitting up of the Association in 1943. In 1945, the new interim government that assumed power after the country was defeated in the war, banned the Turul Association.

*Turul—a sort of falcon or hawk—was an ancient totem bird of Hungarian pre-Christian, tribal mythology, and has been the symbol of military virtues and patriotism for centuries. Turul was also the favorite symbol of the radical right in Hungary during the interwar period.

The ceremonial assembly of the Turul Association at the Vigadó in Budapest

Magyar Világhíradó 610. October 1935

Hungarian, with English subtitles, 1’02”

Hungarian National Film Fund

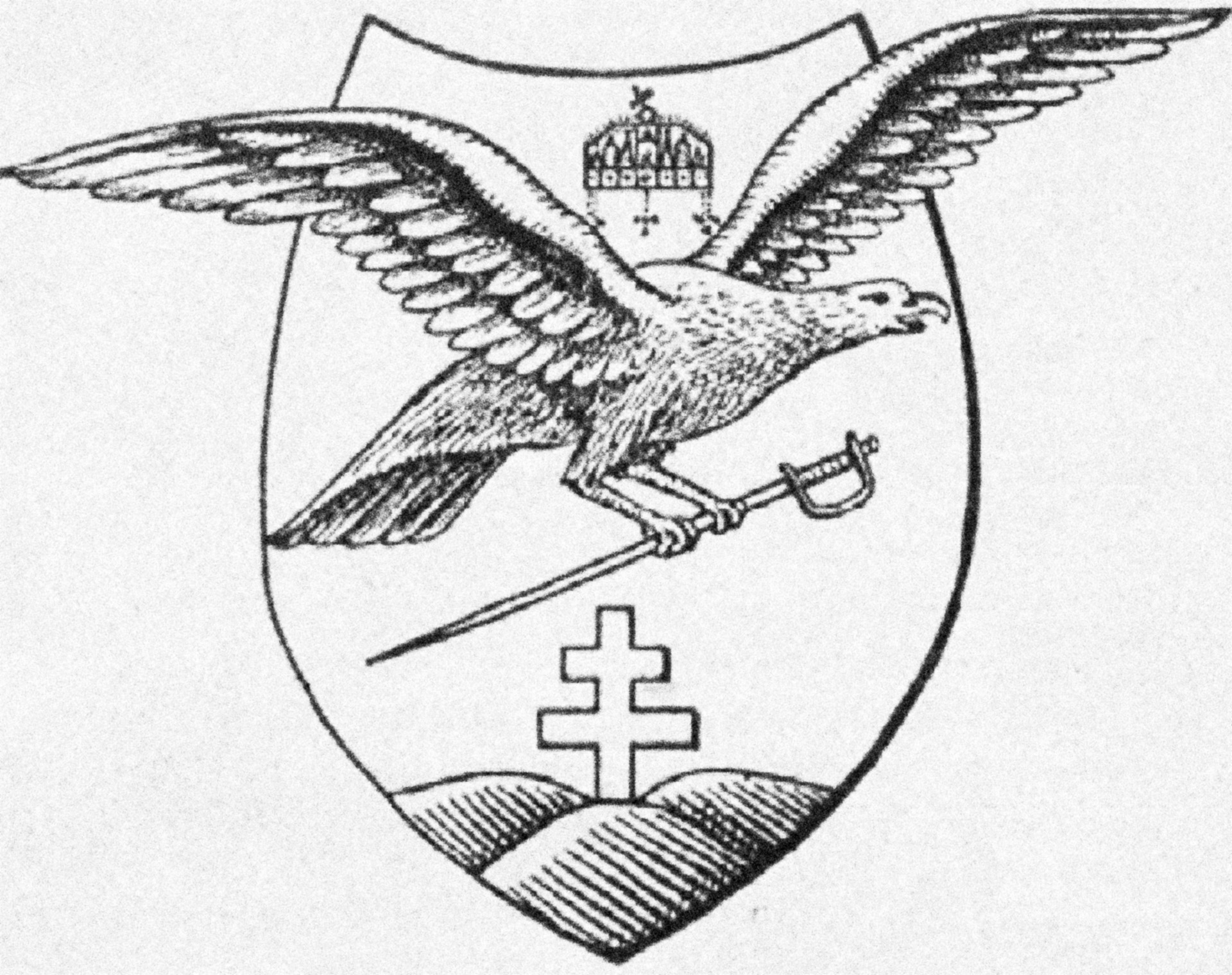

The emblem of the Turul Association, 1933

ephemera, exhibition print

Bercsényi Futár, A Turul Szövetség pécsi kerületének röpirata [Bercsényi Courier, The pamphlet of the Pécs district of the Turul Association], 1933:1

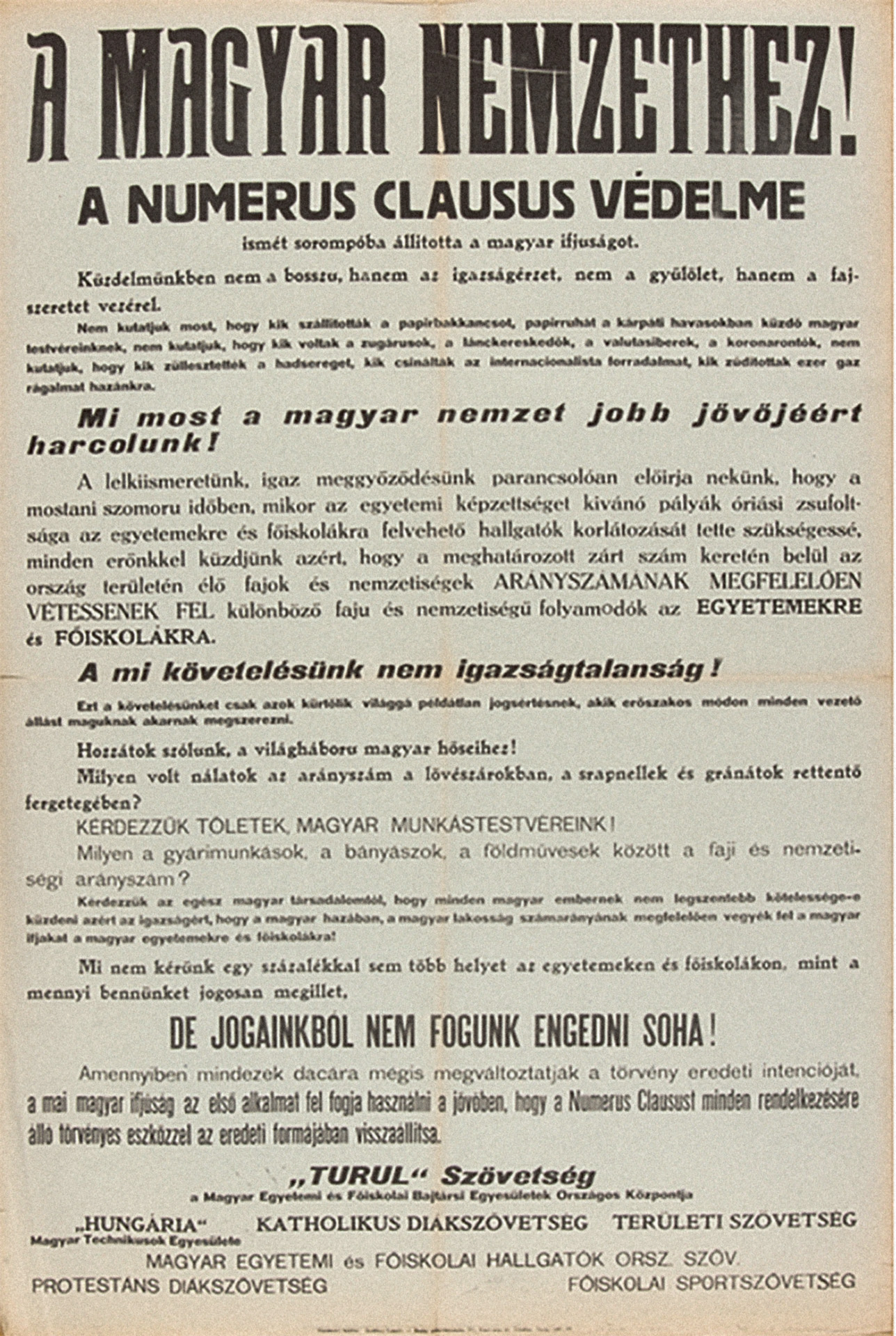

Poster of the “Turul” Association, in defense of the “Numerus Clausus” law, 1920s

poster, exhibition print

Hungarian National Museum – Poster Collection, Budapest, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Prime Minister Gyula Gömbös (in the middle) with the leaders of the Turul Association (The main leader of the Association, József Végváry is standing to Gömbös’s left), 1933

bw. photo, exhibition print

wikimedia commons

In the 1920s, Gyula Gömbös politicized as the founding president of the far-right Racial Defense Party [Fajvédő Párt], which acted as an opposition to the system. For Gömbös, “racial defense” was a socio-political agenda the primary goal of which was the economic and cultural welfare of the Hungarians, and on the other hand to limit the forces—in this case, the Jews as scapegoats—that he considered as obstacles in his agenda. The racial aspect came in with the fact that the Racial Defense Party would not have restricted Jews on religious grounds, but would have extended the restriction to all Hungarian citizens of Jewish origin. As this enterprise remained unsuccessful, Gömbös dissolved the party and returned to the Nemzeti Egység Pártja [National Party of Unity, NEP]. When he took office in October 1932, he felt compelled to state the following in his first parliamentary speech as Prime Minister: “I have revised my position; I now wish to regard that part of Jewry which acknowledges a community of fate with the nation in a fraternal fashion and in the same manner as my Hungarian brothers.” Despite this revised position, Gömbös’s government and party agenda, the National Work Plan [Nemzeti Munkaterv], contained hidden elements that adversely affected the economic situation of the Jews. In the 1930s Hungary was not yet subject to direct German pressure to discriminate against the Jews. Even so, several Hungarian political figures—for instance, Darányi and Béla Imrédy—argued that, in anticipation of the growing German influence, measures should still be taken to restrict the Jews, but these attempts were unsuccessful until 1938. At that time, however, the two houses of Parliament both voted in favour of the discriminatory law, which, under the guise of “creating a balance” limited the proportion of Jews in business and professional life to 20 per cent.

Jewish Man, c. 1935

bw. photo, exhibition print

Fortepan / Zoltán Aszódi

„Legyen béke…” [Let there be peace] Dr. Leo Buday-Goldberger on program of the OMIKE [Országos Magyar Izraelita Közművelődési Egyesület, National Hungarian Jewish Cultural Association], 1935

exhibition print

Egyenlőség – A Magyar zsidóság politikai hetilapja [Equality – The political weekly of Hungarian Jewry], Ferbruary 2, 1935 / omike.hu

The Horthy-regime did not formulate its central Roma policy, and as a result, the so-called “Gypsy question” fell entirely into the hands of the ministries and local authorities. The “stray Gypsies”, who were in the minority in the Hungarian Roma population (estimated at about one hundred thousand), were mostly dealt with through the tools of law enforcement, while the public health approach became decisive in the case of the Roma population living in segregated settlements. Most of these Roma people lived in a state of hardship; their living conditions were documented by village researchers and social documentary photographers, among others. Roma people in larger cities lived in slightly better conditions, while “Gypsy” musicians were able to make a decent living for themselves by entertaining the wealthier in society. “Gypsy” music belonged to the national self-image during this period; taking advantage of this social prestige, the musicians established the Magyar Cigányzenészek Országos Egyesülete [National Society of Hungarian Gypsy Musicians]. After its dissolution in 1933, they formed the Magyar Cigányzenészek Országos Szövetsége [National Association of Hungarian Gypsy Musicians] from 1935 to act together in order “to protect their common material, moral and intellectual interests”. The organization successfully lobbied both at the Ministry of the Interior and the leadership of the capital, and they also fought, among others, with the leadership of Hungarian Radio (for higher wages). In 1937, the Association also organized a nationwide event-series to celebrate the 500th anniversary of the settlement of the Roma in Hungary. For a long time, despite the popularity of “Gypsy” music, folk music research did not deal with the songs played by “Gypsy” musicians. Composer Béla Bartók considered it necessary to say in his lecture at the general assembly of the Magyar Néprajzi Társaság [Hungarian Ethnographic Society] in 1931: “What you call gypsy music is not gypsy music. It is not gypsy music, but Hungarian music: it is a new-type of Hungarian folk music that is only played by Gypsies for money (because—according to tradition—playing music for money is not a gentlemanly thing to do); this music is Hungarian because it is, almost without exception, composed by Hungarian gentlemen.” “Gypsy” music was distinguished by musicologists from real Hungarian folk music on the one hand, and from authentic Roma folk music on the other—more precisely, they were generally unwilling to even accept its existence. The discovery of authentic Roma culture had to wait until the appearance of the Roma folklore movement in Hungary in the 1970s.

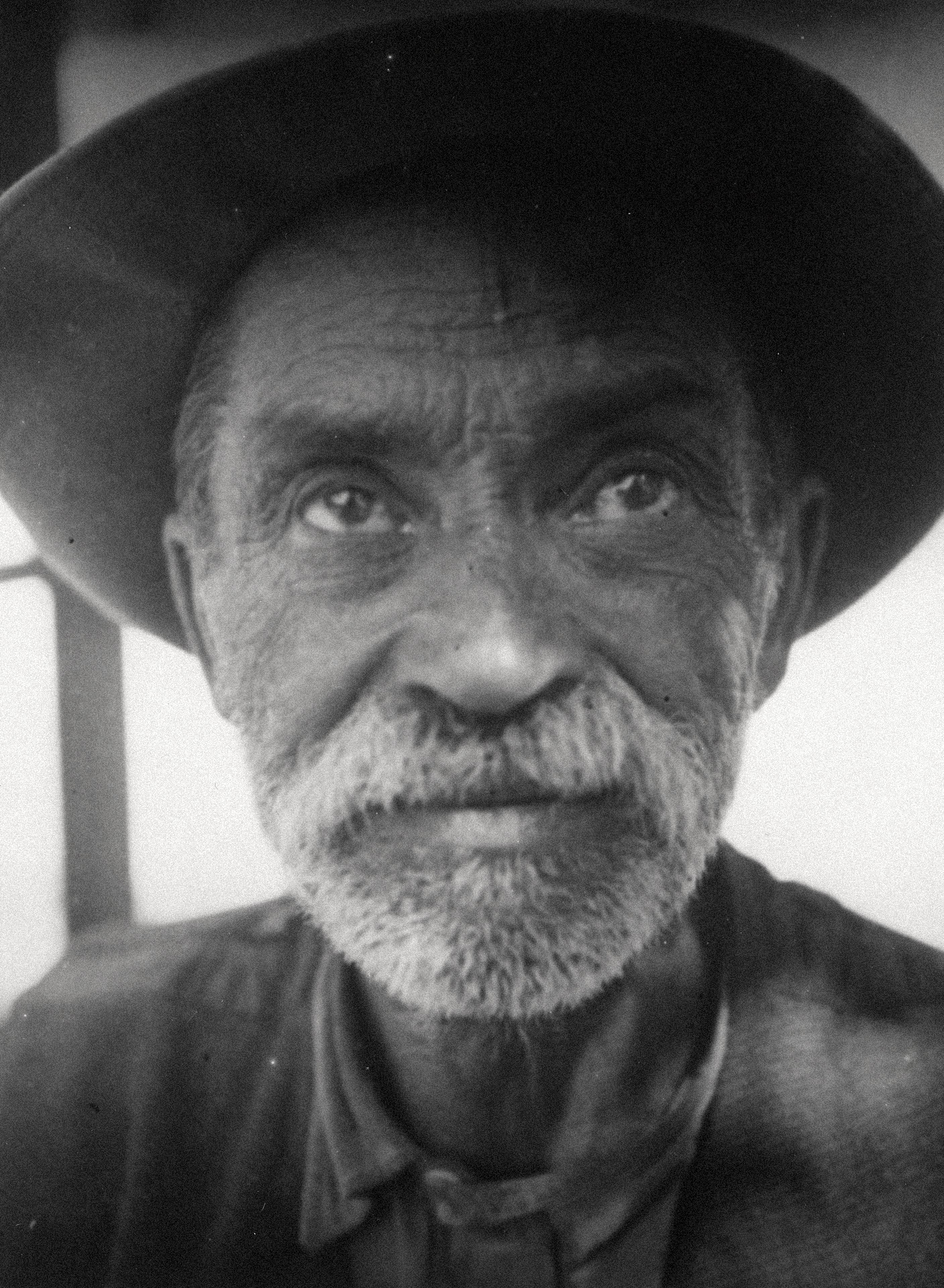

Kata Kálmán, Idős cigányférfi portréja [Portrait of an Old “Gypsy” Man], 1935

bw. photo, exhibition print

Hungarian Museum of Photography, Kecskemét

Jenő Laki Farkas, leader of a “Gypsy” band, and his family, 1935

bw. photo, exhibition print

Fortepan / Jenő Farkas

“Gypsy” musicians, with American filmactor Douglas Fairbanks and English film actress Sylvia Ashley, Budapest, 1935

bw. photo, exhibition print

Fortepan / Sándor Bojár

The economic crisis became even worse after 1931: in the wake of European bankruptcies, foreign creditors withdrew all cancellable loans. According to various calculations, the rate of economic decline may have been about 7 to 16.5% between 1929 and 1933. The crisis affected the different sectors of society to varying degrees. The exceptionally high living standards of the bourgeoisie, the large landowners and the upper-middle class were hardly affected, even during the years of the crisis. On the other hand, the living conditions of the peasantry, workers, artisans and retailers, (who made up the vast majority of the population), as well as the various civil servants and intellectuals deteriorated sharply. Improvement was brought about by a change in external economic conditions around 1932: among other things, all compensation payments were cancelled under an international agreement. Gömbös’ reform plan was also successful, as discussed earlier, so a recovery began after 1934. The rate of growth by the end of the 1930s (compared to 1929) was set at 6-13% according to various calculations.

TESZ – Exhibition Week of Hungarian National Produce (design by György Konecsni), 1934

lithography, exhibition print

Budapest Poster Gallery

Prime Minister Gyula Gömbös at the General Assembly of GyOSz (National Association of Industrialists), left Miksa Fenyő and Jenő Vida, right Lóránt Hegedűs, Ferenc Chorin, Pál Bíró, Albert Hirsch and Leó Goldberger de Buda, 1933

bw. photo, exhibition print

Hungarian National Museum – Historical Photo Department, Budapest, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Ferenc Haár, Téglahordó [A worker carrying bricks], 1935

bw. photo, exhibition print

Hungarian Museum of Photography, Kecskemét

Indeed, the lifestyles of the social groups less affected by the crisis (the bourgeoisie, the large landowners and the upper-middle class) did not change much during the 1930s. By the middle of the decade, economic recovery was also being felt by the lower strata of society. The tensions of contemporary Hungarian society and politics were also benevolently disguised by the economic boom, and only a few people seemed to be threatened by the darkening skies looming over Europe.

Garden Party in the Buda Castle, 1937

bw. photo, exhibition print

Hungarian National Museum – Historical Photo Department, Budapest, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Ball of the “Vitéz” Order, the debutantes are being introduced to Horthy, c. 1935.

bw. photo, exhibition print

Hungarian National Museum – Historical Photo Department, Budapest, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Woman in goggles for quartz lamps, 1925

bw. photo, exhibition print

Fortepan / Ákos Lőrinczi

The Hungarian Jazz Band, 1934

bw. photo, exhibition print

Fortepan / Private Photo and Film Archive – Tibor Höfler collection

The Hungarian Home Movies collection at the Blinken Open Society Archives contains hundreds of hours of footage. These films were shot by upper middle-class or middle-class people, predominantly in the 1920s and 1930s. The images invoke good and well lived lives; lives of awe-inspiring, successful entrepreneurs, creative inventors and investors, doctors, engineers, lawyers, and artists – members of the bourgeoisie.

The lives captured in these films, however, are a world apart from the lives of the industrial workers living in crowded, run-down tenement buildings in Ferencváros or Angyalföld, depicted in Attila József’s poems. Or from those Hungarian agricultural laborers living in the pusta, immortalized by Gyula Illyés. These lives existed parallel to one another.

In this video etude we have chosen images from Iván Fischer’s home movies collection from the 1930s. The people appearing in the piece are Iván and Ádám Fischer’s uncle’s family and friends. The images were shot in Hűvösvölgy, at Alsóörs, Balatonfüred and, of course, Budapest. Watching the images of a peaceful and wonderfully rich life in interwar Hungary, we, the viewers are aware of the dark parallels, just as well of the anti-Jewish laws of the 1930s, and their devastating social and economic consequences.

Curator: Zsuzsa Zádori (Blinken Open Society Archives)

Video editor: Darius Krolikowski (Blinken Open Society Archives)

Music: Béla Bartók Mikrokosmos no. 45-51.

Special thanks to Péter Forgács, Iván Fischer and Ádám Fischer.

Parallels. Fischer Family Home Movies, Budapest, Alsóörs, 1930s

video, 5’24“ (2021)