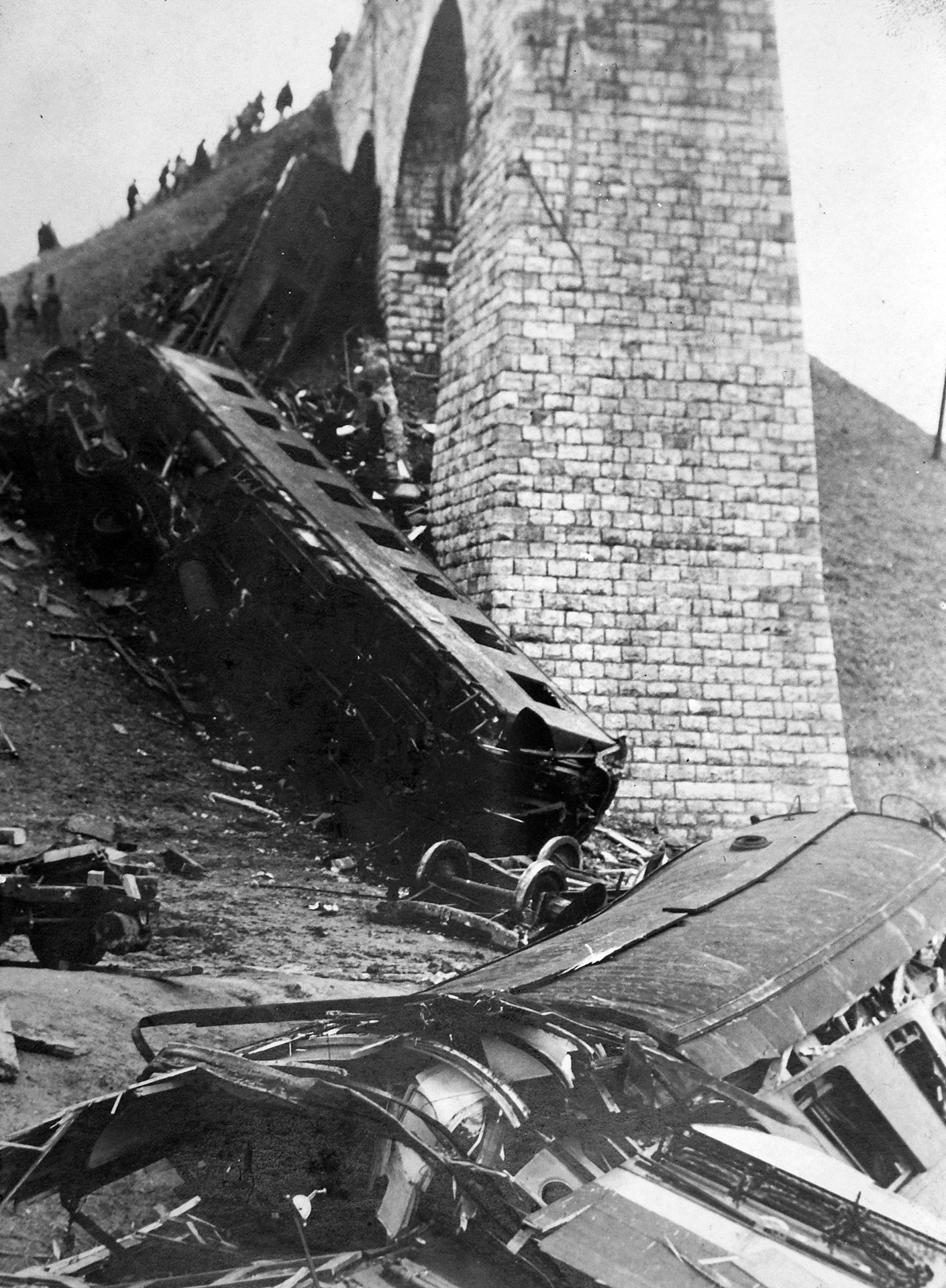

The secret police of the Horthy era (and within that, the Spherical Government) paid close attention to controlling political extremists. However, the Royal Hungarian State Police did not succeed in liquidating both sides of the political spectrum—the Communists and the various party formations of the Hungarist movement—with exactly the same efficiency. The head of the political police was Deputy Chief Captain Imre Hetényi, who had led the area since the mid-1920s. Under the leadership of Hetényi, the Political Police Department pushed back illegal left-wing movements on all fronts by the mid-1930s. After the infamous bomb attack of the railway bridge at Biatorbágy in September 1931, a state of siege was proclaimed and a nationwide man-hunt for KMP-activists was unleashed. Two leaders of the Party, Imre Sallai and Sándor Fürst were captured, sentenced to death and executed in a martial law procedure in 1932, although they (or the Party) had nothing to do with the bomb attack. Most of the KMP-activists were also detained (like Mátyás Rákosi or Zoltán Vas) or were forced to emigrate. During the continuous raids, Attila József also “got busted” in February 1933: in connection with a Communist movement organized among the university youth, where he was accused of “demanding and exciting the violent overthrow of the legal order of the state and society” with his poem Lebukott [Busted]. (The case had no major consequences for him).

While this way the police successfully repressed various left-wing organizations, , they were unable to take effective action against the Arrow Cross and far-right organizations that became active in the mid-1930s. But it was not Hetényi’s fault; he also tried to take action against the Arrow Cross and other National Socialist-inspired organizations with the full rigor of the law. However, the actions sparked attacks by far-right forces. German-friendly politicians and members of the state apparatus sympathetic to the Arrow Cross (several members of the General Staff and the Army, as well as the commanders of the gendarmerie) expected the realization of the Hungarian revisionist goals only from Nazi Germany. Nor could the conservative government elite entirely escape this. The “fascization” experienced in Hungarian domestic politics became decisive in the operation of the state to such an extent that it even reached the position of the powerful police chief, Imre Hetényi. The organizer of the Political Law Enforcement Department was sent into retirement in 1938.

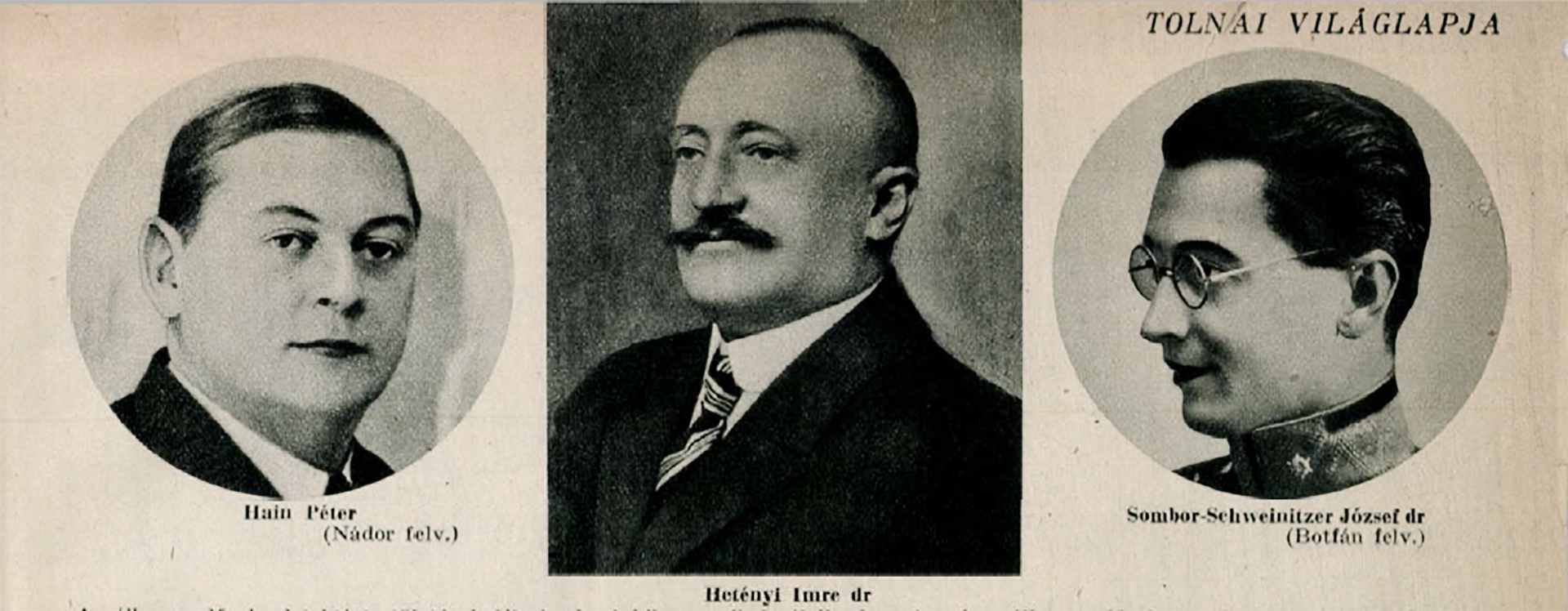

Péter Hain Detective Inspector, Dr Imre Hetényi, Deputy Chief of Staff, József Sombor-Schweinitzer, Police Advocate Genaral, 1937

exhibition print

Tolnai Világlapja, October 1, 1937 / Arcanum

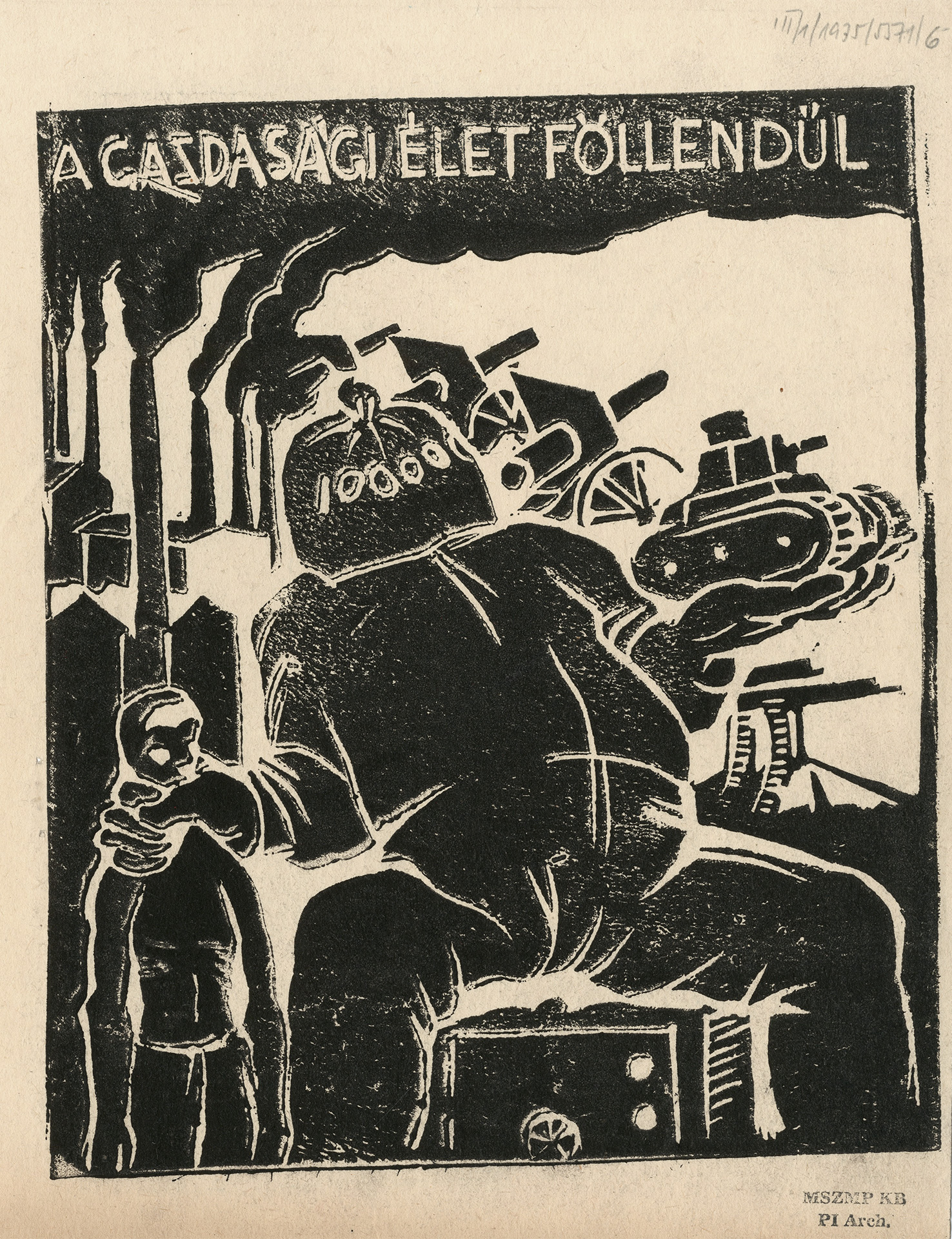

Sándor Józsa, A gazdasági élet fellendül [The Economy is Booming], 1935

linocut, flyer of the KMP – Party of Communists in Hungary

Institute of Social History, The Archives of Political History and Trade Unions, Budapest

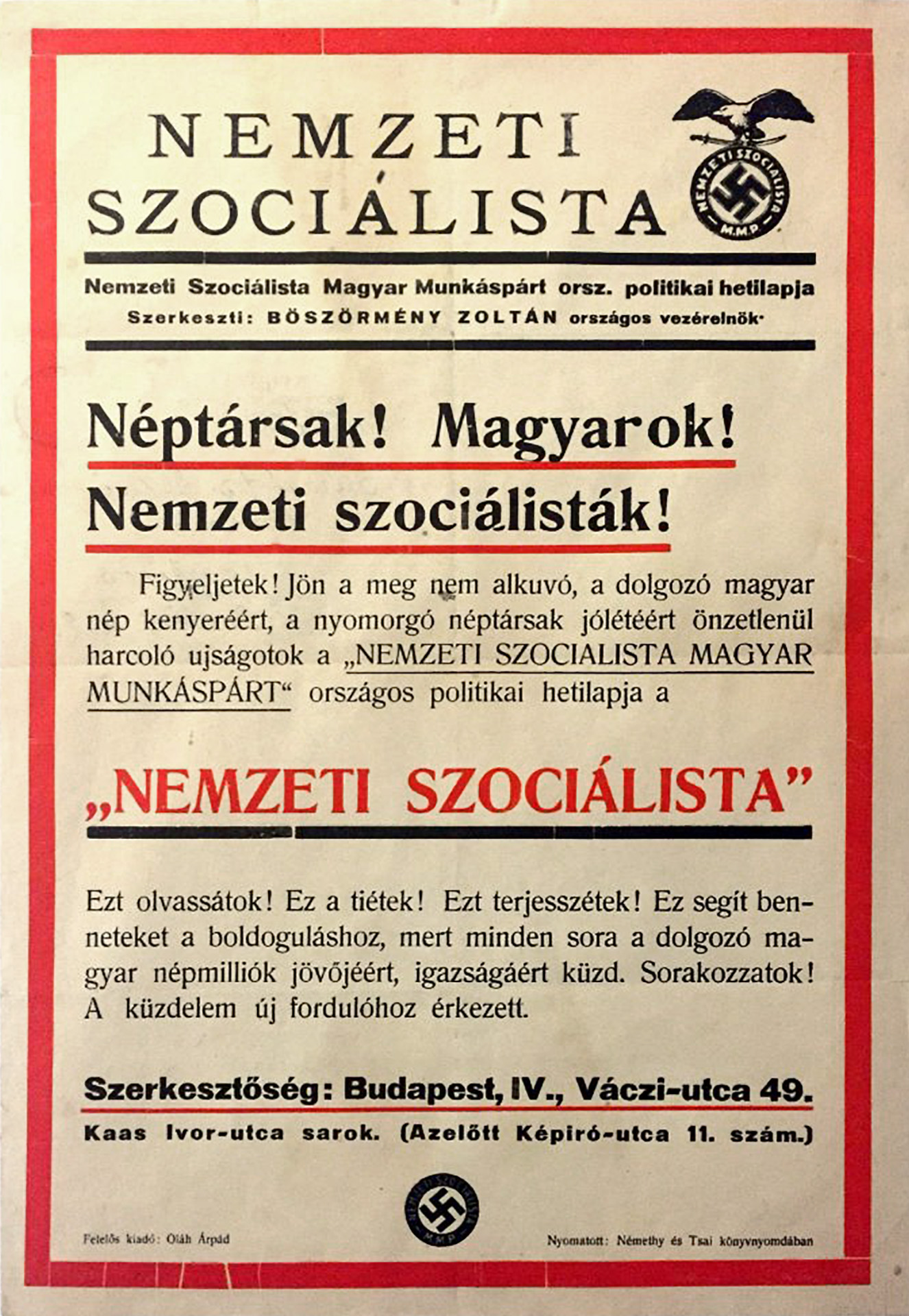

Poster of the National Socialist Hungarian Workers’ Party [Nemzeti Szociálista Magyar Munkás Párt], (Scythe-Cross Movement), c. 1936

ephemera, exhibition print

fasiszmustortenete.blog.hu

The Communist Party of Hungary [KMP, Kommunisták Magyarországi Pártja, Party of Communists in Hungary] was established in November 1918, after the war defeat and the collapse of the historical Hungarian Kingdom, and the proclamation of the new republic. The founders were mostly former prisoners of war who returned home from Soviet-Russia, where, after the outbreak of the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, they joined the international Communist movement. In Spring 1919, they even managed to take power for a couple of months (Hungarian Soviet Republic).

Following the demise of the short-lived Hungarian Soviet Republic, the Communist Party was banned in Hungary and it could operate only underground, in illegality until late 1944. As a political organization, it functioned as the Hungarian branch of the international communist movement under the aegis of the Comintern. Its political profile and actions were determined by the actual instructions of the Soviet party leadership and the heads of the Hungarian Party living in emigration in Moscow. Due to this fact, and to the perpetual persecution of the Hungarian political police, the domestic party network, despite the reiterated efforts of regroup and reorganization, remained weak, consisted of just a few hundred members and sympathizers and played less than a marginal role in Hungarian domestic political life. Its efforts and activities were practically limited to self-sustainment, conspiracy and hiding from the political police.

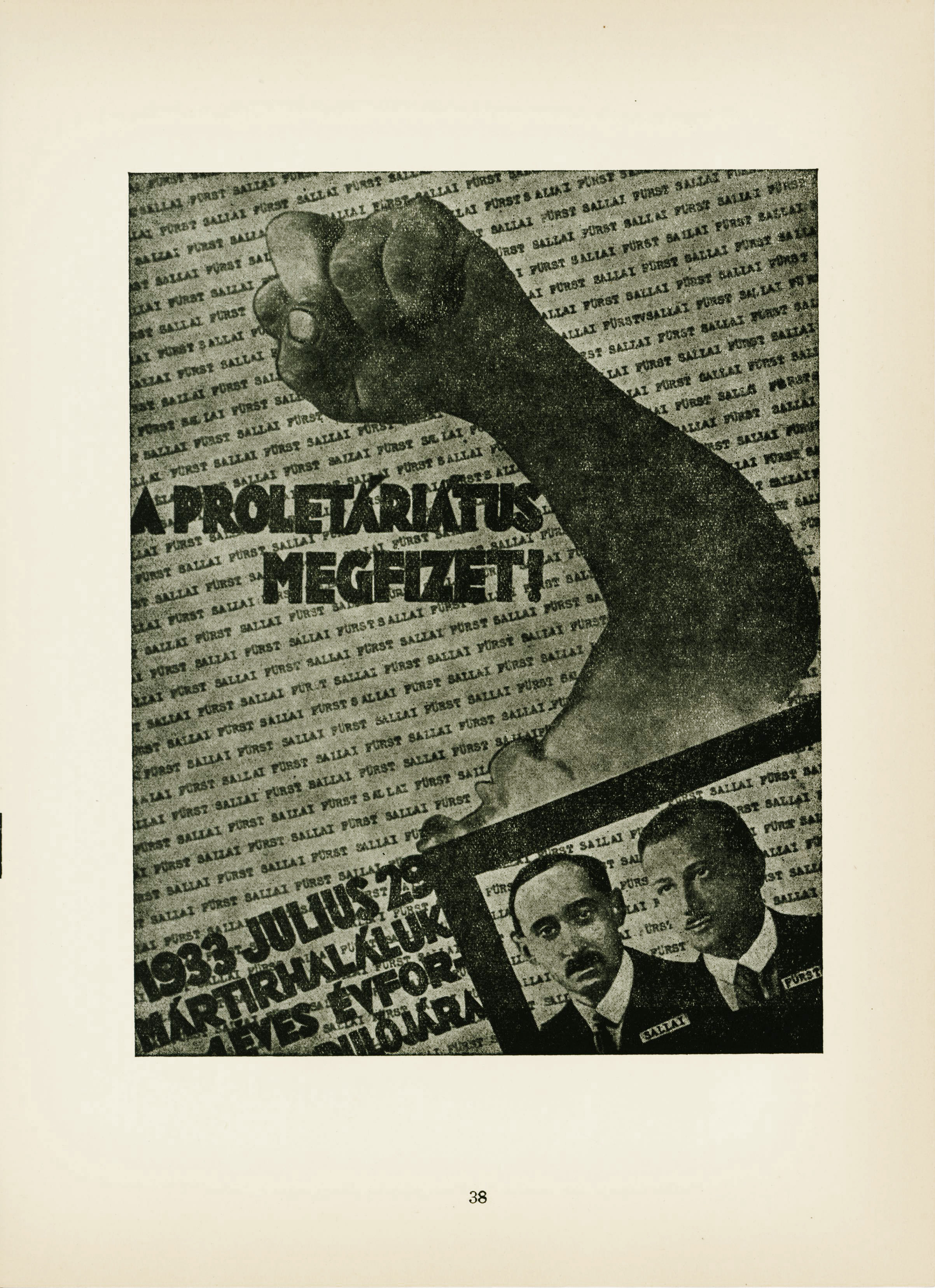

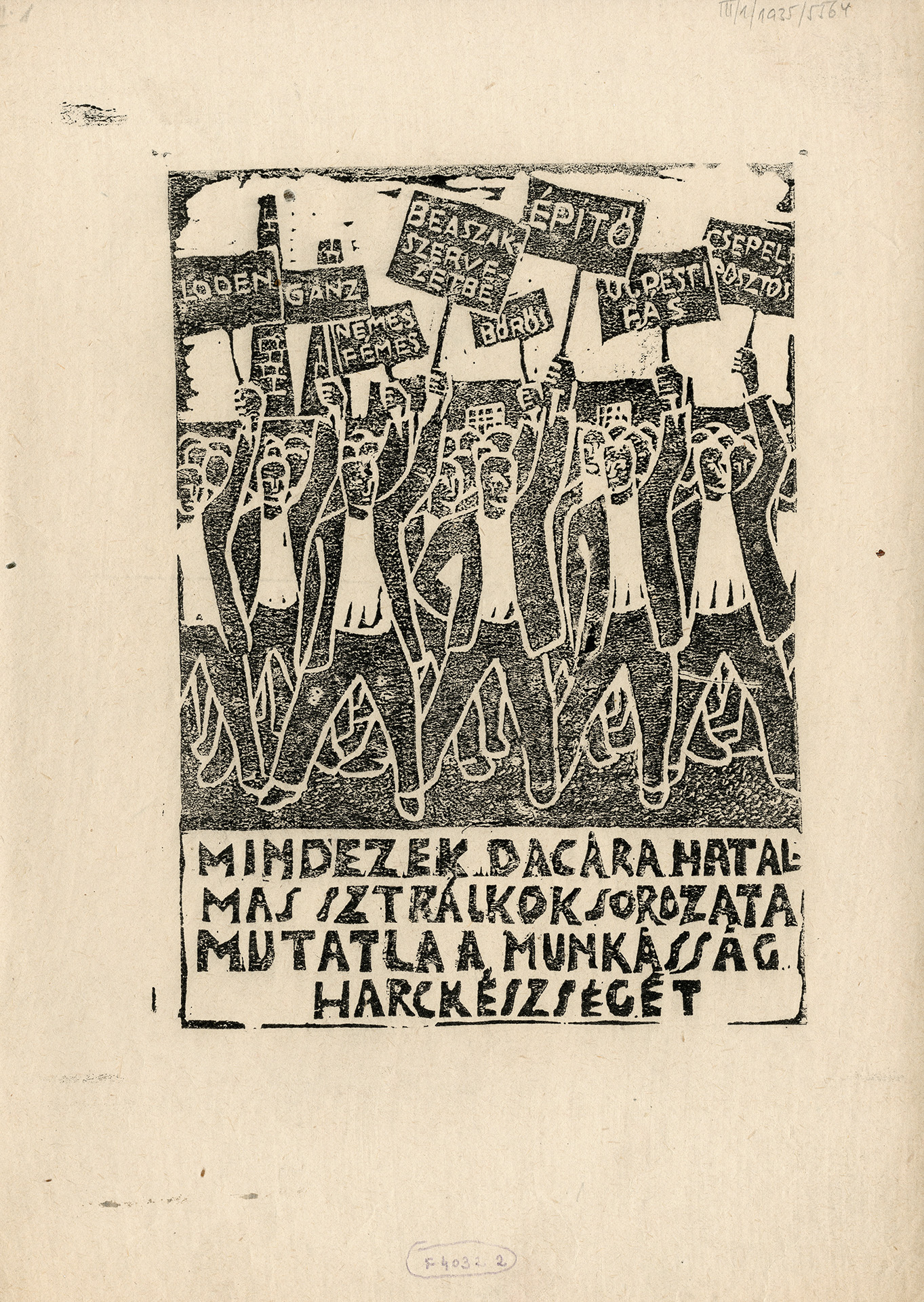

Viewing the wide-scale and growing disaffection among the people caused by the Great Depression, the Communists in Moscow and in Hungary saw a promising opportunity to expand the organizational basis and enhance their political influence. They believed that general discontent might lead to a revolutionary outbreak in which the Communists should take the leading role again, like it happened in Spring, 1919. This expectation was based upon the total ignorance and neglect of the domestic situation and the political realities. The weak and isolated KMP network, which was urged from Moscow to pursue a more aggressive propaganda and execute more spectacular political actions, was an easy prey for the Hungarian political police. After the fatal bomb attack of the railway bridge at Biatorbágy in September 1931, that demanded dozens of casualties. A state of siege was proclaimed and a nationwide man-hunt for KMP-activists was unleashed. Two leaders of the Party, Imre Sallai and Sándor Fürst were captured, sentenced to death and executed in a martial law procedure in 1932, although they (or the Party) had nothing to do with the bomb attack. Most of the KMP-activists were also detained or forced to emigrate.

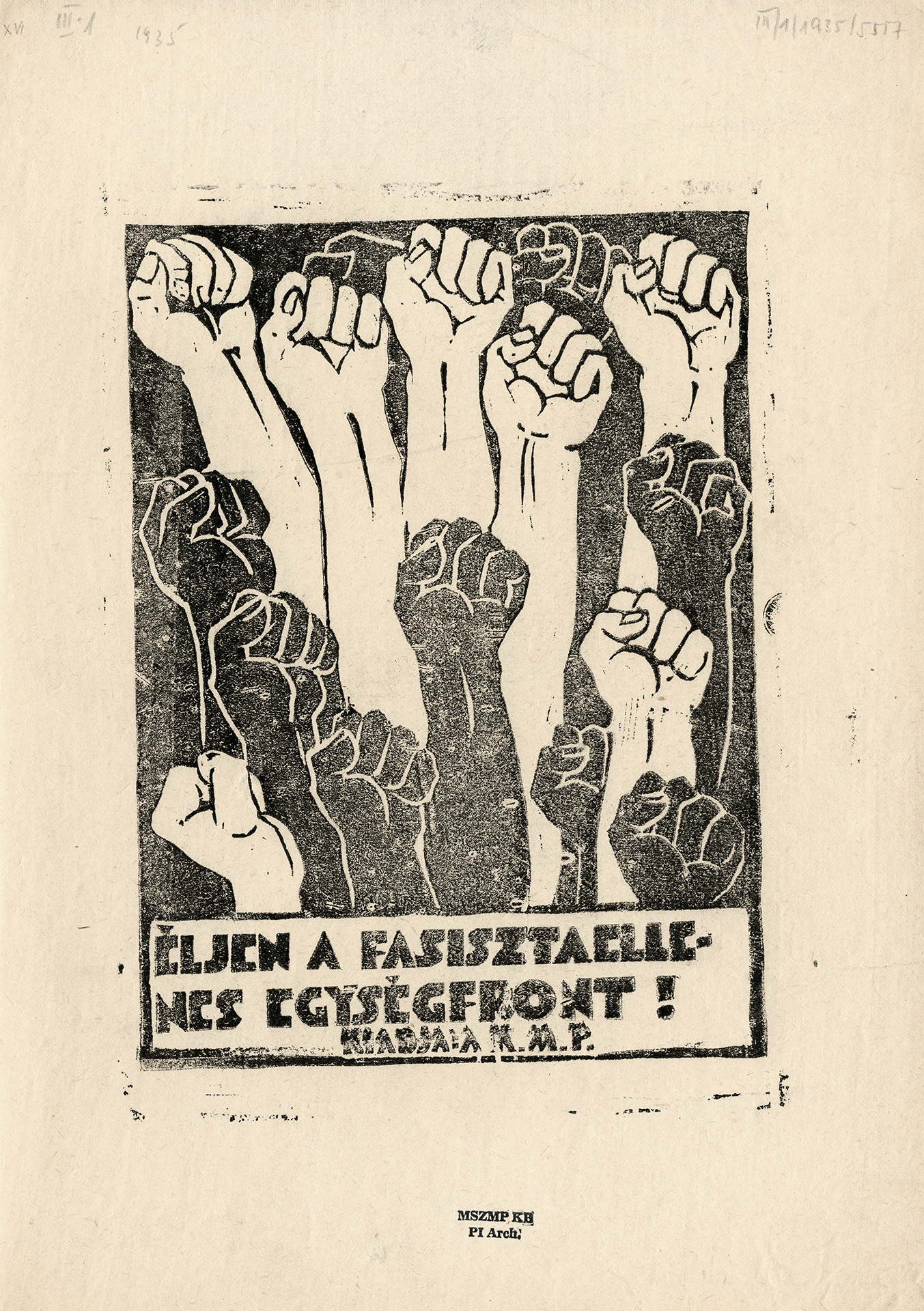

The resolutions of the 7th Congress of the Comintern in 1935 that announced the new popular front policy, brought a change into the political line of the KMP as well. The policy of sharp opposition that previously stigmatized even the Social Democrats as “social fascists” and enemies—and, by this, contributed to a great extent to the collapse of the Weimar Republic and Hitler’s takeover in Germany—was replaced by a more reconciliatory tactics of seeking alliance with non-Communist, democratic and anti-Fascist parties and movements: in Hungary with the Social Semocrats, the trade unions, the circles of populist writers and the newly re-established Smallholders’ Party [Kisgazadpárt], in the name of defending the common democratic principles and values. Some of the leading figures of the KMP took part in the foundation of the anti-Fascist March Front [Márciusi Front] in 1937. In addition, the new popular front line enabled the KMP to attract a wider pool of potential sympathizers. The underground Party even instructed its members and followers to join in (political) incognito other parties and movements—even Facsist or extreme-right organizations—, that enjoyed legality and, and as so, provided a sort of protective shield that could enhance the chances of illegal conspiracy and enabled those crypto-Communist members to shape the political lines of these organizations in favor of the Communist tactical and strategic aims from inside. A new change in this policy line was brought again by the Hitler–Stalin (Molotov–Ribbentrop) Pact in August 1939.

The organizational basis and the political influence of the KMP did not become significantly stronger with the popular front tactics. In the mobilization of the dissatisfied masses of workers and poorer peasantry, the extreme right, arrow cross movements were much more successful. However, during these years a new generation of young intellectuals, university students and young workers joined the illegal Communist movement. Many of the outstanding Communist politicians of the post-1945 era became members or sympathizers of the KMP from the first half of the 1930s, including László Rajk Sr., who was executed in a show trial in 1949; Géza Losonczy, who was killed during the post-1956 retorsions in the Nagy Imre trial; two other defendants of the very same trial, Ferenc Donáth and Miklós Vásárhelyi, who became prominent dissident figures of the Kádár-era; János Kádár himself, the ruler of the Hungarian Party-state between 1956 and 1988; or György Aczél, the most prominent figure of culture politics throughout the Kádár-regime, who joined the Communist party at the age of 18 in 1935.

The Biatorbágy railway viaduct after the bomb attack on September 13, 1931

bw. photo / exhibition print

Fortepan / Fortepan

Montázs-csoport [Montage Group], A proletariátus megfizet! [The proletariat will even the score!], c. 1933

(In the right corner: Imre Sallai and Sándor Fürst.)

photomontage, flyer of the KMP – Party of Communists in Hungary, facsimile

[Küzdtünk híven a forradalomért. Képes röplapok az illegalitás idejéből (We Fought Faithfully for the Revolution. Flyers from the Time of Illegality). Budapest: Kossuth Könyvkiadó, 1961]

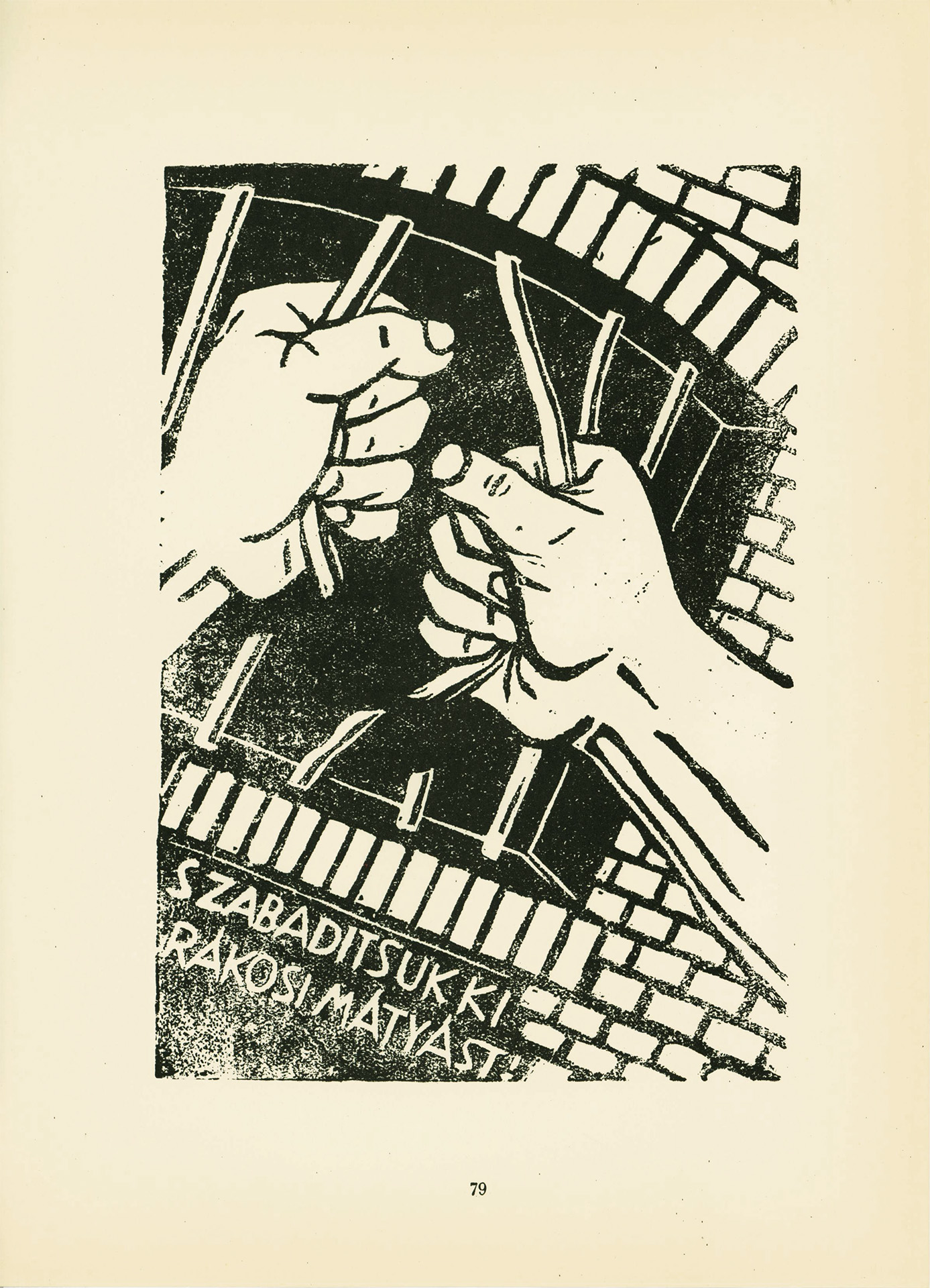

Endre A. Fenyő, Szabadítsuk ki Rákosi Mátyást! [Let’s free Mátyás Rákosi!], 1934

linocut, flyer of the KMP – Party of Communists in Hungary, facsimile

[Küzdtünk híven a forradalomért. Képes röplapok az illegalitás idejéből (We Fought Faithfully for the Revolution. Flyers from the Time of Illegality). Budapest: Kossuth Könyvkiadó, 1961]

Károly Háy, Éljen a fasizmus elleni egységfront! [Long live the united front against Fascism!], 1935

linocut, flyer of the KMP – Party of Communists in Hungary

Institute of Social History, The Archives of Political History and Trade Unions, Budapest

Károly Háy, Mindezek dacára hatalmas sztrájkok sorozata mutatja a munkásság harckészségét [Despite All This, a Series of Huge Strikes Shows the Fighting Spirit of the Workers], 1935

linocut, flyer of the KMP – Party of Communists in Hungary

Institute of Social History, The Archives of Political History and Trade Unions, Budapest

Manifesto of the March Front [Márciusi Front], 1937

ephemera

Institute of Social History, The Archives of Political History and Trade Unions, Budapest

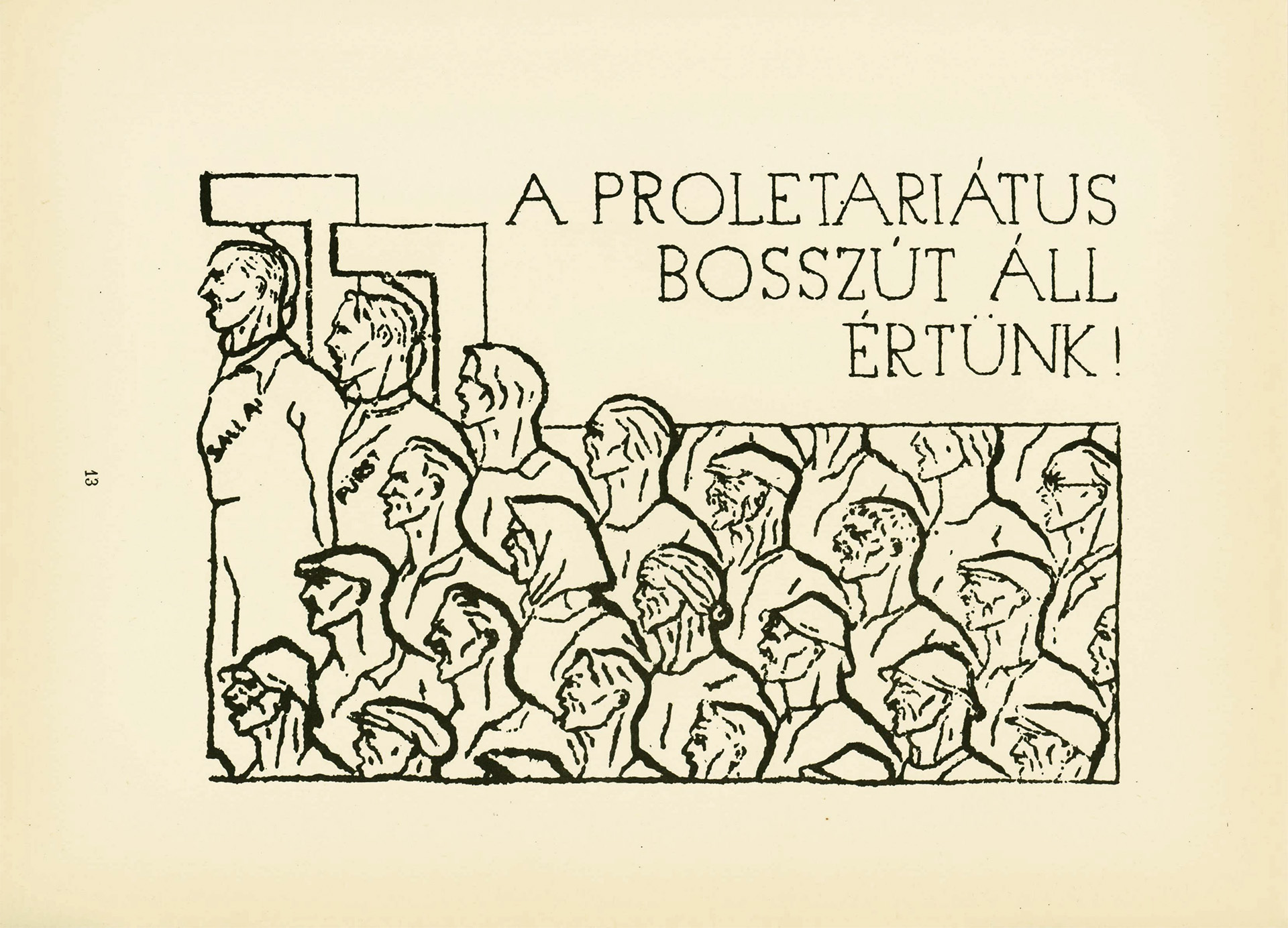

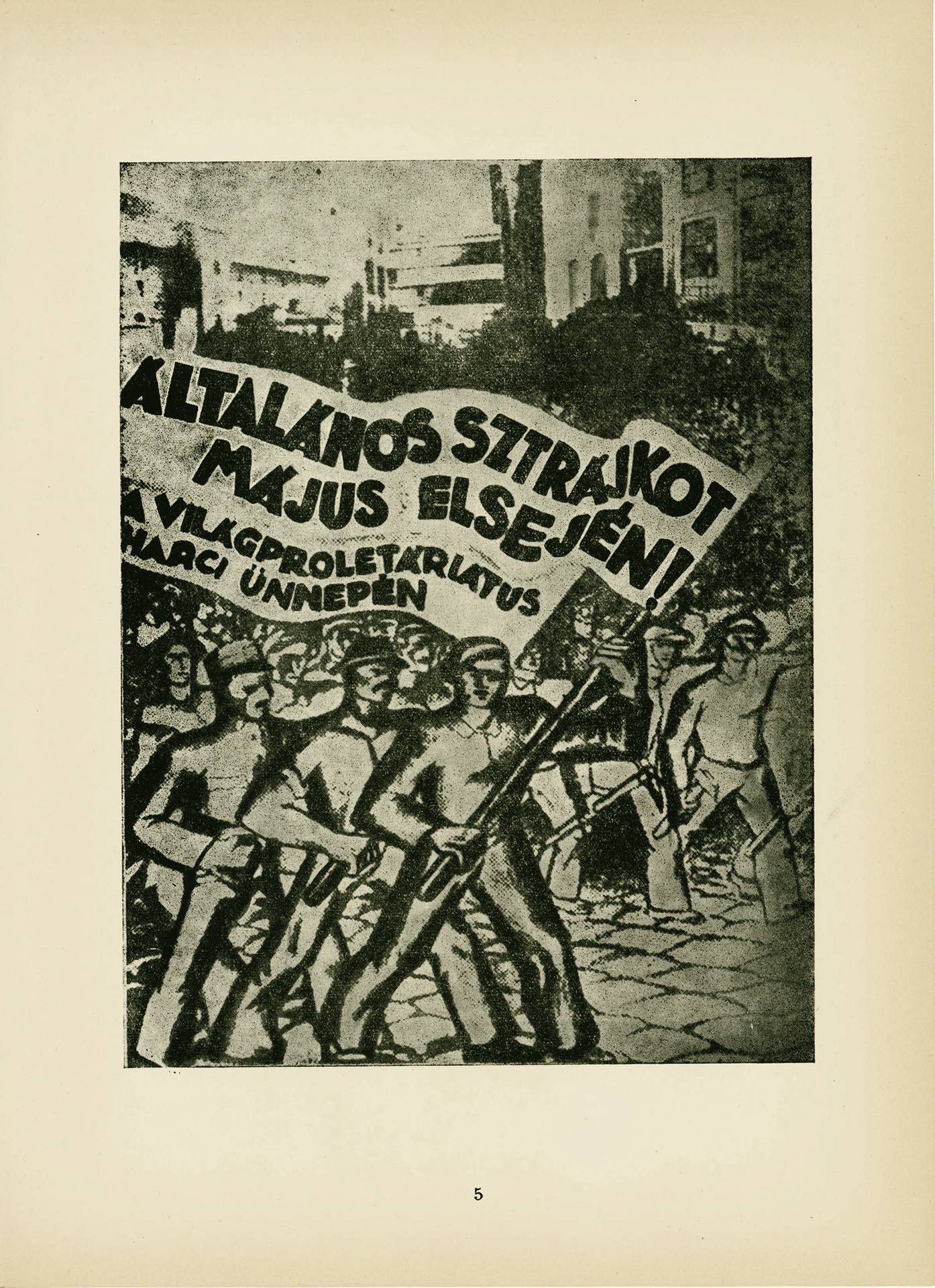

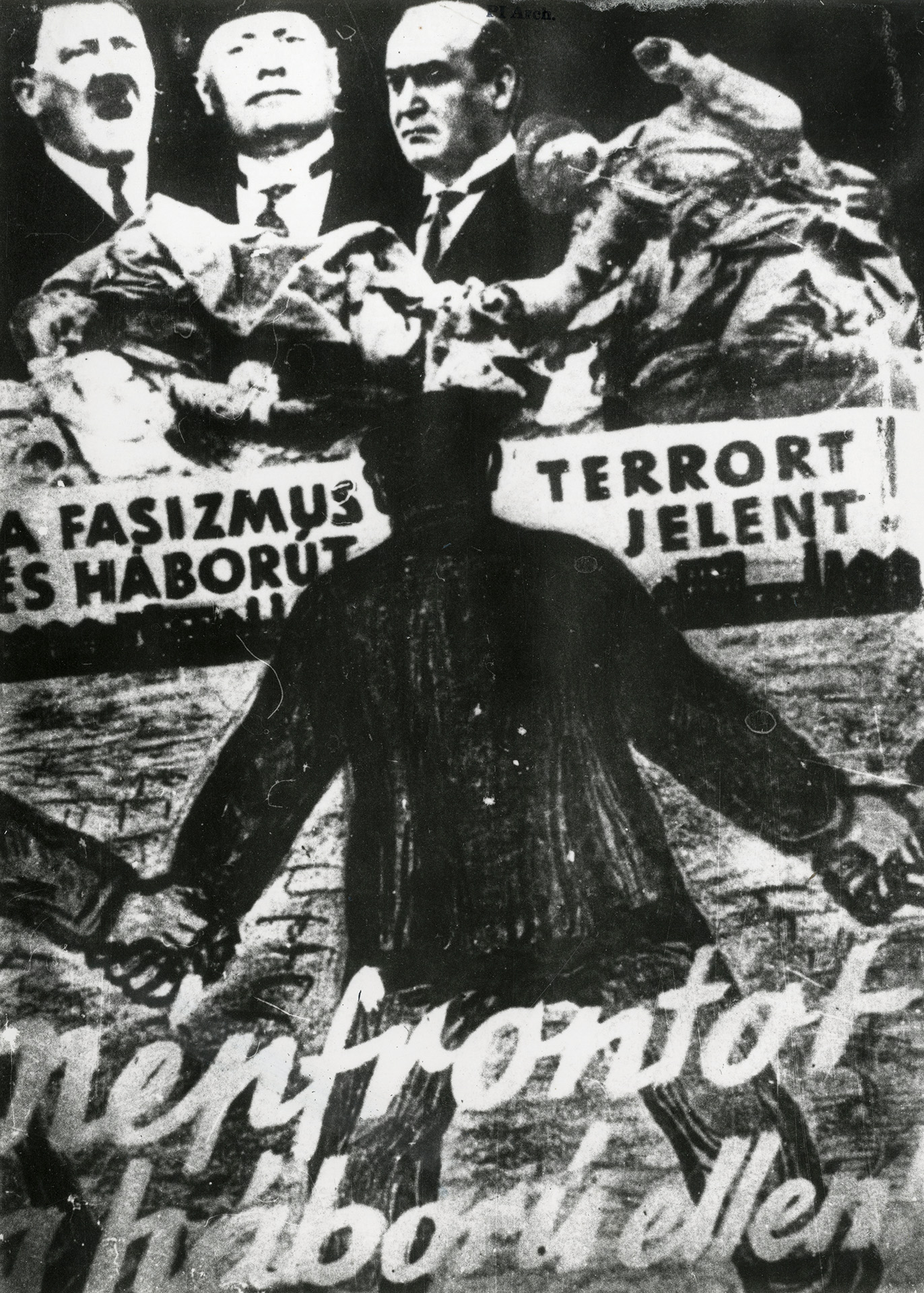

The Communist Party of Hungary (KMP), operating illegally in the 1930s, published countless leaflets, many of which were designed by renowned artists. The leaflets were designed by the Montázs Group [Montage Group] from around 1932, which partly overlapped with the Group of Socialist Artists; its members were Béla Bán, Endre A. Fenyő, György Goldman, Károly Háy, Andor Sugár, Dezső Révai and Tibor Bass. Károly Háy had worked for the Party even before that, using sometimes the most rudimentary techniques to create images for the flyers and leaflets. According to his recollections: “After the party reorganized its press apparatus, leaflets and flyers were regularly published by the party and organizations like the KIMSZ [Kommunista Ifjúmunkások Magyarországi Szövetsége, Hungarian Association of Communist Youth Workers], and the Red Aid. Most of these flyers and pamphlets were reproduced using stencils… It is true that the stencil method confines the possibilities of artistic expressions to rather narrow limits, but we also know from art history that many of these limitations imposed by technology become an inspiring and even style-defining force. In addition, on occasion we could organize the regular publication of linoleum engravings, which is one of the easiest graphic genres suitable for traditional reproduction, and sometimes we could also use the photograph as a reproduction method.”

Károly Háy, A proletariátus bosszút áll értük! [The Proletariat is Taking Revenge on Them !], 1932

stencil engraving, flyer of the KMP – Party of Communists in Hungary, facsimile

[Küzdtünk híven a forradalomért. Képes röplapok az illegalitás idejéből (We Fought Faithfully for the Revolution. Flyers from the Time of Illegality). Budapest: Kossuth Könyvkiadó, 1961]

Montázs-csoport [Montage Group], Általános sztrájkot május elsején!... [General Strike on May Day!...], c. 1932

photomontage, flyer of the KMP – Party of Communists in Hungary, facsimile

[Küzdtünk híven a forradalomért. Képes röplapok az illegalitás idejéből (We Fought Faithfully for the Revolution. Flyers from the Time of Illegality). Budapest: Kossuth Könyvkiadó, 1961]

Montázs-csoport [Montage Group], A fasizmus terrort és háborút jelent! Népfrontot a háború ellen! [Fascism Means Terror and War! Popular Front Against the War!], 1935

photomontage, flyer of the KMP – Party of Communists in Hungary

Institute of Social History, The Archives of Political History and Trade Unions, Budapest

Extreme right, National Socialist and racial protection ideas had been already and massively present in Hungarian political life from the early 1920s. Therefore, one cannot say that those copied parallel German (or Italian) models and organizations: they were genuine Hungarian initiatives and ideas. Moreover, Hungarian racial protection did not focus only on the “Jewish threat”, but many of their representatives also demanded the restriction of the influence and expansion of „Germans” (assimilated Hungarians of German origin) in Hungarian political life.

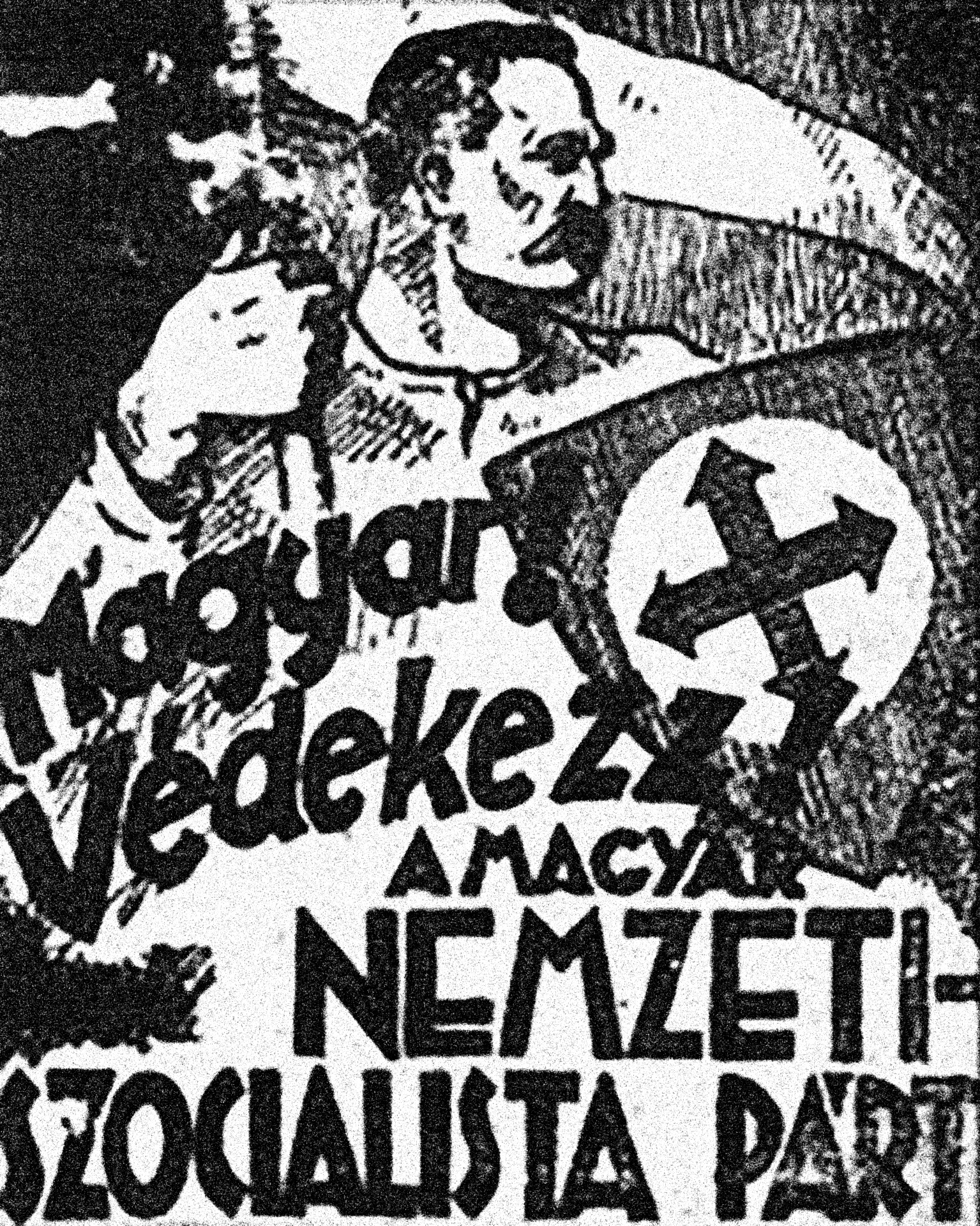

The 1929 Great Depression gave a big impetus to the expansion of the extreme right. The Scythe-Cross Movement [Kaszáskeresztesek] founded and led by Zoltán Böszörmény was able to step forward as a political party already in 1932; and Zoltán Meskó, an extreme right wing MP, could also establish his own independent party, the Hungarian National Socialist Workers and Peasant Party [Magyar Nemzeti Szocialista Földműves és Munkás Párt] in the very same year. Yet, these proto-Arrow Cross parties, and the National Will Party [Nemzeti Akarat Pártja] founded by Ferenc Szálasi in 1935, still could not achieve a breakthrough on the 1935 general elections. However, in 1939 the (then already unified) Arrow Cross Party [Nyilaskeresztes Párt] gained 40% of the votes in those districts where they were able to run candidates. By that time, the number of the party members arose to appr. 300 thousand.

The background of this spectacular expansion can be described shortly as follows: the Social Democratic Party [MSZDP – Magyarországi Szociáldemokrata Párt, Social Democratic Party of Hungary], which was forced to make a deal with the ruling forces (the Bethlen–Peyer Pact) in 1921 that bound and paralyzed its own organizational capacities and political potentials, was not radical enough for the masses of the petty bourgeoisie, the workers and peasantry that became more and more dissatisfied and indignated by the social inequalities and the rigid, closed, elitist, aristocratic, authoritarian cast-like political regime. On the other hand, the Communist Party [KMP – Kommunisták Magyarországi Pártja, Party of Communists in Hungary] remained “alien” and practically invisible for them. It is quite telling that the extreme right movements and politicians broke ahead most in areas where the Social Democrats lost space and influence. By the second half of the decade the Arrow Cross activists gained majority influence in the traditional bastions of the Social Democrats, the trade unions of iron workers and miners.

The attractive force of Arrow Cross movements did not lie solely in their extreme nationalist, antisemitic slogans and their peculiar type of national-historical mythology (Hungarism). They announced a radical anticapitalistic and anti-regime program that showed numerous similarities with the social and economic ideas of the Communists. They rejected the „liberal-capitalist” system (dominated by the “Jews”), proclaimed the nationalization of grand capital and the big industrial enterprises, envisaged central planning and administration of the national economy, outlined radical egalitarian ideas in income distribution (state-regulated and maximized personal income). All in all, they promised a total and dictatorial reconstruction of the state, the economy and the social relations. The kinship with the Communist program was so close that some of the top leaders of the arrow cross party, like Ödön Málnási or István Péntek, in fact, arrived to the movement from the illegal Communist Party. On the surface, the difference between the Arrow Cross and the Communist offer lied only in the former’s nationalism, racism and militant antisemitism. Many of those Arrow Cross functionaries who were tried for war crimes after the war, defended themselves during the interrogations with the argument that, although with slightly different means, they pursued the same goal as the Communists: the eradication of the “people-skinning capitalist and aristocratic order”.

This program did not attract only the less-educated petty bourgeoisie, the workers and the poorer peasantry, but seduced qualified intellectuals as well. Some prominent representatives of the populist writers floated fairly close to the Arrow Cross Party, and in 1933 the poet Attila József also devoted some thoughts to these ideas in his short essay, The National Communism [A nemzeti kommunizmus].

The state power tried to halt the advance of the Arrow Cross movement by the restrictions and manipulations of the election system, then also attempted to winding them up. In 1937 Szálasi’s party was banned, and soon he was detained and imprisoned for anti-state crimes. Despite these measures, on the 1939 parliamentary elections the party with Kálmán Hubay in the lead achieved a great success.

During the war years the popularity of the Arrow Cross Party decreased. Due to the economic prosperity of the war economy the unemployment rate went down, the salaries raised and in the state of war the government introduced further curtailments of the political rights. The Arrow Cross Party could step on the scene only in October 15, 1944, when with German support it took the power in a coup d’etat and introduced a blood-handed dictatorship. After the war Szálasi and the top leaders of his party were sentenced to death and executed for war crimes.

Flyer of the National Socialist Hungarian Workers’ Party [Nemzeti Szociálista Magyar Munkás Párt] (Scythe-Cross Movement), c. 1936

ephemera, exhibition print

fasiszmustortenete.blog.hu

The anthem of the National Socialist Hungarian Workers’ Party [Nemzeti Szociálista Magyar Munkás Párt], (Scythe-Cross Movement), Zoltán Böszörményi, c. 1936

ephemera, exhibition print

fasiszmustortenete.blog.hu

“Hungarian! Defend yourself!”, Poster of National Socialist Hungarian Workers’ Party [Nemzeti Szociálista Magyar Munkás Párt] (Scythe-Cross Movement), Zoltán Böszörményi, c. 1936

ephemera, exhibition print

fasiszmustortenete.blog.hu

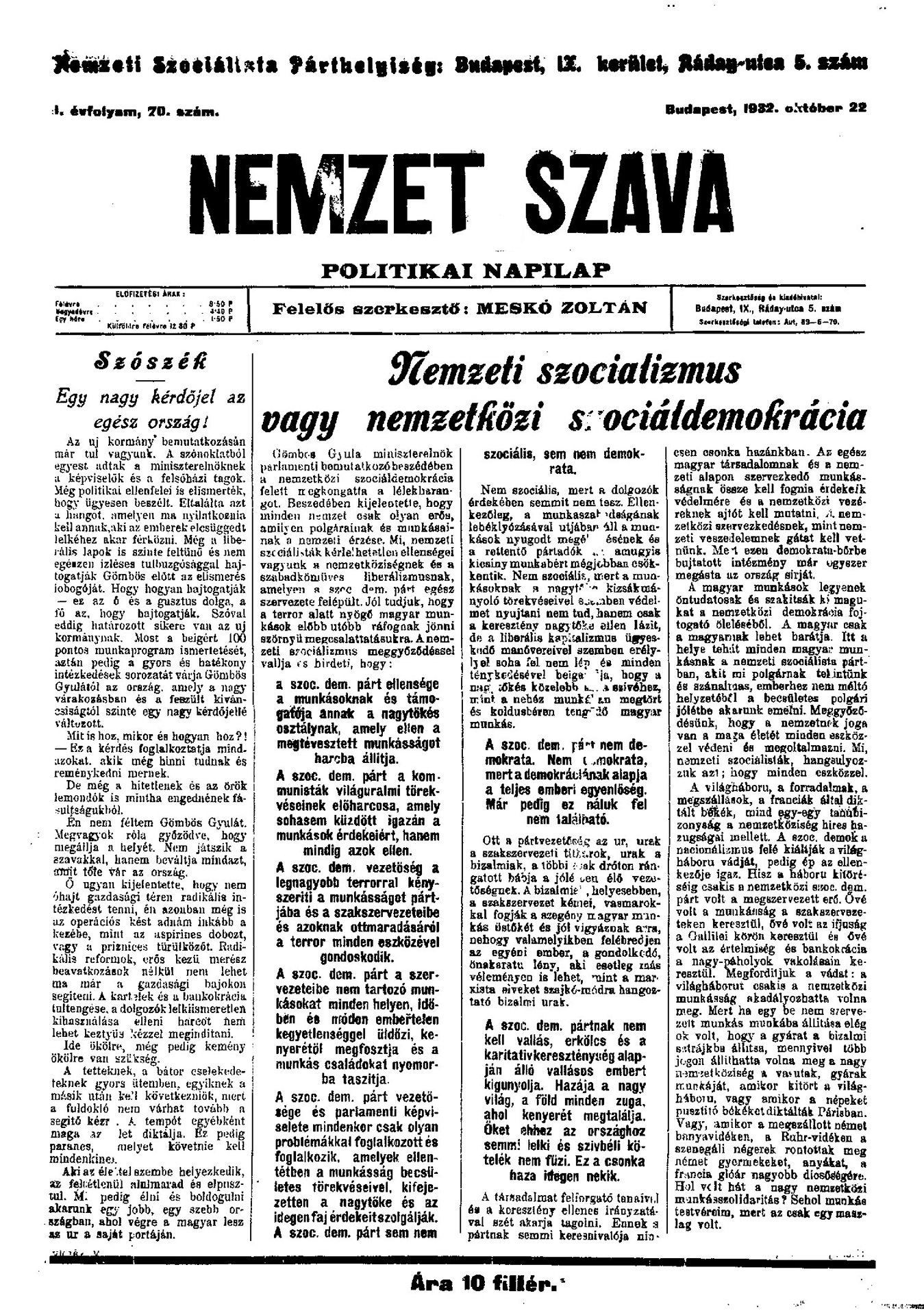

Nemzet szava [The Voice of the Nation], the weekly (later bi-weekly) newspaper of the Hungarian National Socialist Workers and Peasant Party [Magyar Nemzeti Szocialista Földműves és Munkás Párt], October 22, 1932

exhibition print

mediatortenet.wordpress.com

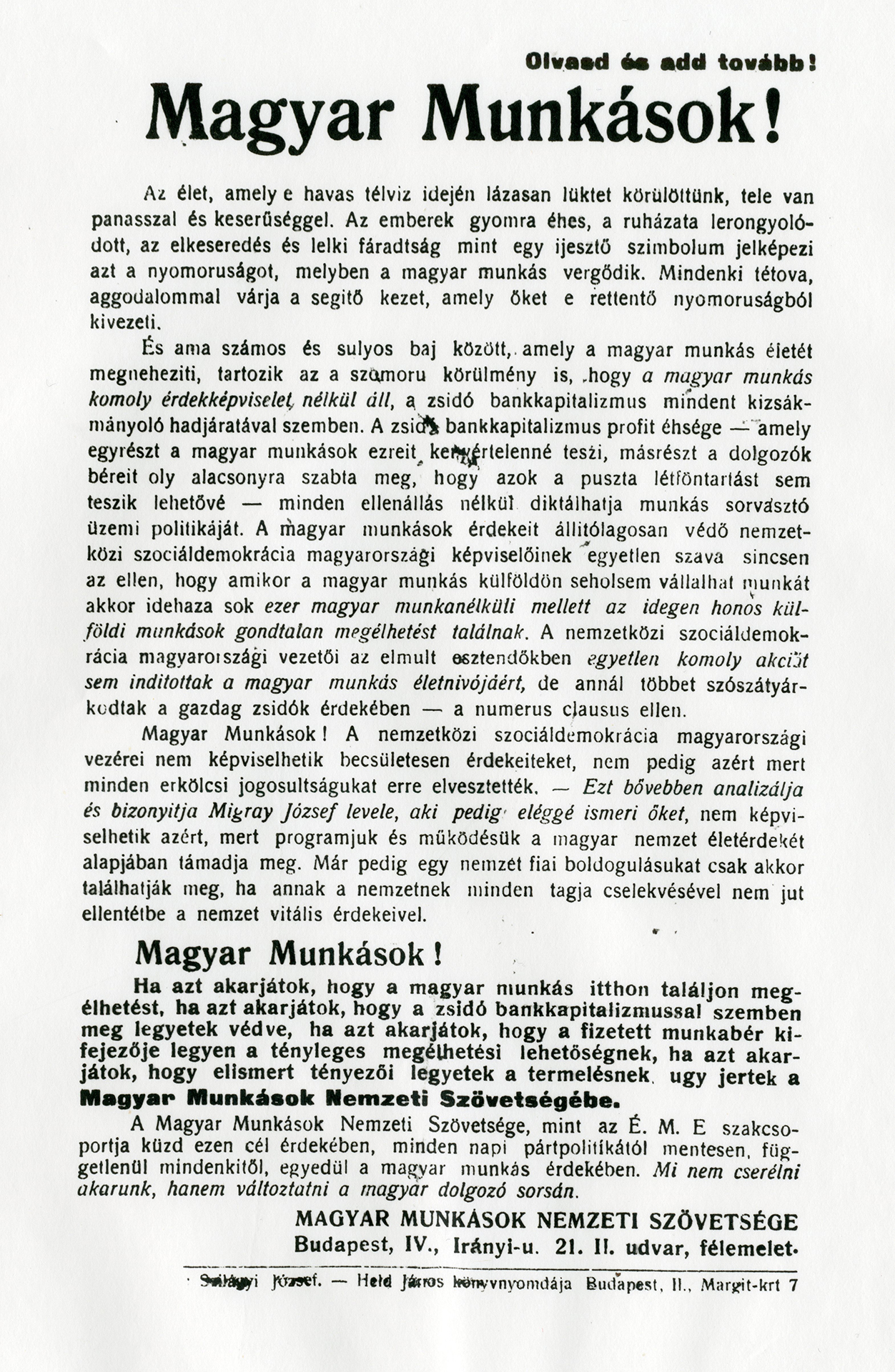

“Hungarian Workers!", poster of the National Association of Hungarian Workers [Magyar Munkások Nemzeti Szövetsége], second half of the 1930s

ephemera, exhibition print

Institute of Social History, The Archives of Political History and Trade Unions, Budapest

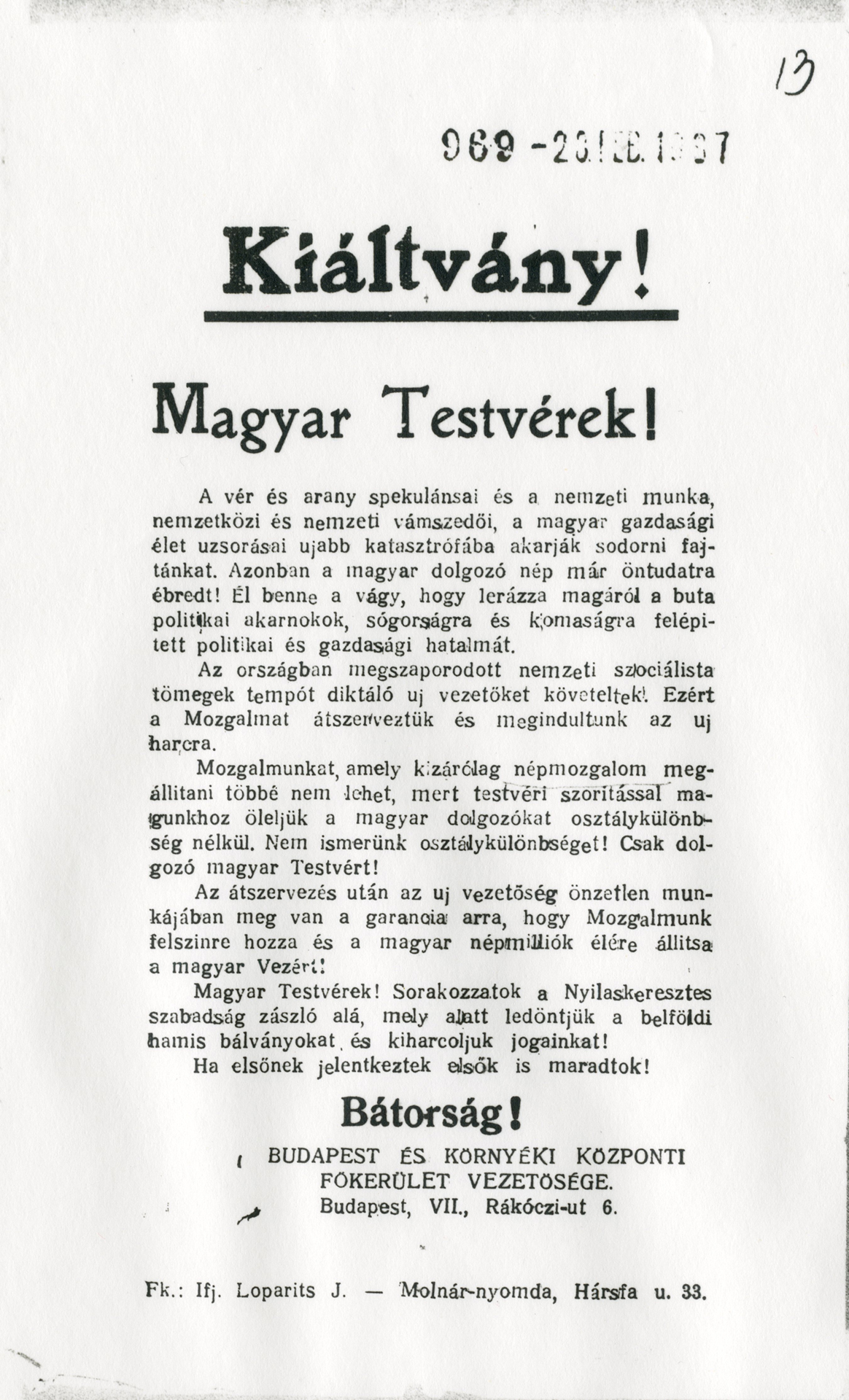

Manifesto of the Arrow Cross movement, second half of the 1930s

ephemera, exhibition print

Institute of Social History, The Archives of Political History and Trade Unions, Budapest

Testvér! Az ígéretekből elég volt! Rend! Becsület! és Fegyelem! [Brother! That was Enough of the Promises! Order! Honor! and Discipline!], 1937 körül

flyer of the Racial Protection Socialist Party, exhibition print

Múzeum Antikvárium, Budapest