In the words of literary historian Pál Ács, “...Attila József’s national, patriotic poetry of incomparable beauty is structured around the themes of his own—if you like, evangelical—poverty. It is not the poet who is the reason why ‘national poverty’ is still a threat today." For Attila József, the homeland also evidently meant all those places (abandoned factory yards, gloomy suburban plots), phenomena (unemployment, social injustice) and people (the poor, the suffering) that never were and never are welcome by the authorities.

The period of the poem “A Breath of Air!” in Hungary was, of course, not as dark for everyone as Attila József wrote in his poems. The country had more or less recovered from the economic crisis, and the beneficial veil of the economic boom masked the discontent of those in the depths of society. It is no coincidence that, looking back from today, the face of the era that comes to the fore is one of “peaceful, bourgeois” nostalgia: the world of the new Hungarian sound movies and picture magazines, where little was said about the excesses of power or social injustice. As the historian Ignác Romsics wrote, the “Hungarian system of government of the period is considered to be a limited form of parliamentarism, i.e. one that also contains authoritative elements... The view that considers this system of government to be a totalitarian state of the Nazi or fascist type ignores certain basic facts, as does the view that juxtaposes it with the parliamentary democracies of England, France, Scandinavia or even Czechoslovakia. The Hungarian system, like most Central and Eastern European regimes, is characterized by its transitory nature and by the ‘hybridity’, which is most often described in international literature as authoritarian.”

Several proposals were made to solve the problems: the National Work Plan of Prime Minister Gyula Gömbös; or the Communist Party, which was operating illegally at the time; and the emerging extreme-right parties made different and disparate proposals to remedy the country’s problems. But Hungary has always been in the grip of various great powers, while global politics and the global economy have had a huge impact on domestic processes. Various ideological trends have also infiltrated the sphere of culture, where numerous debates and fronts have emerged among its actors. Like today, there was little transition between the two sides, but there were also many artists who worked tirelessly to reconcile folk and national traditions with progression, and create a world where people of different minds can peacefully live together.

Lajos Petri: The Heroic Monument of the Transylvanian Hussars in Buda Castle, 1935

Tóth Árpád (István Bethlen) promenade, Veli bej rondella

bw. photo, exhibition print

Fortepan / Révay Péter

Béla Kontuly, Miklós Horthy, 1934

oil on canvas, exhibition print

Hungarian National Museum – TK Collection of Paintings, Budapest

Prime Minister Gyula Gömbös on a hunt, c. 1935

bw. photo, exhibition print

Hungarian National Museum – Historical Photo Department, Budapest, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

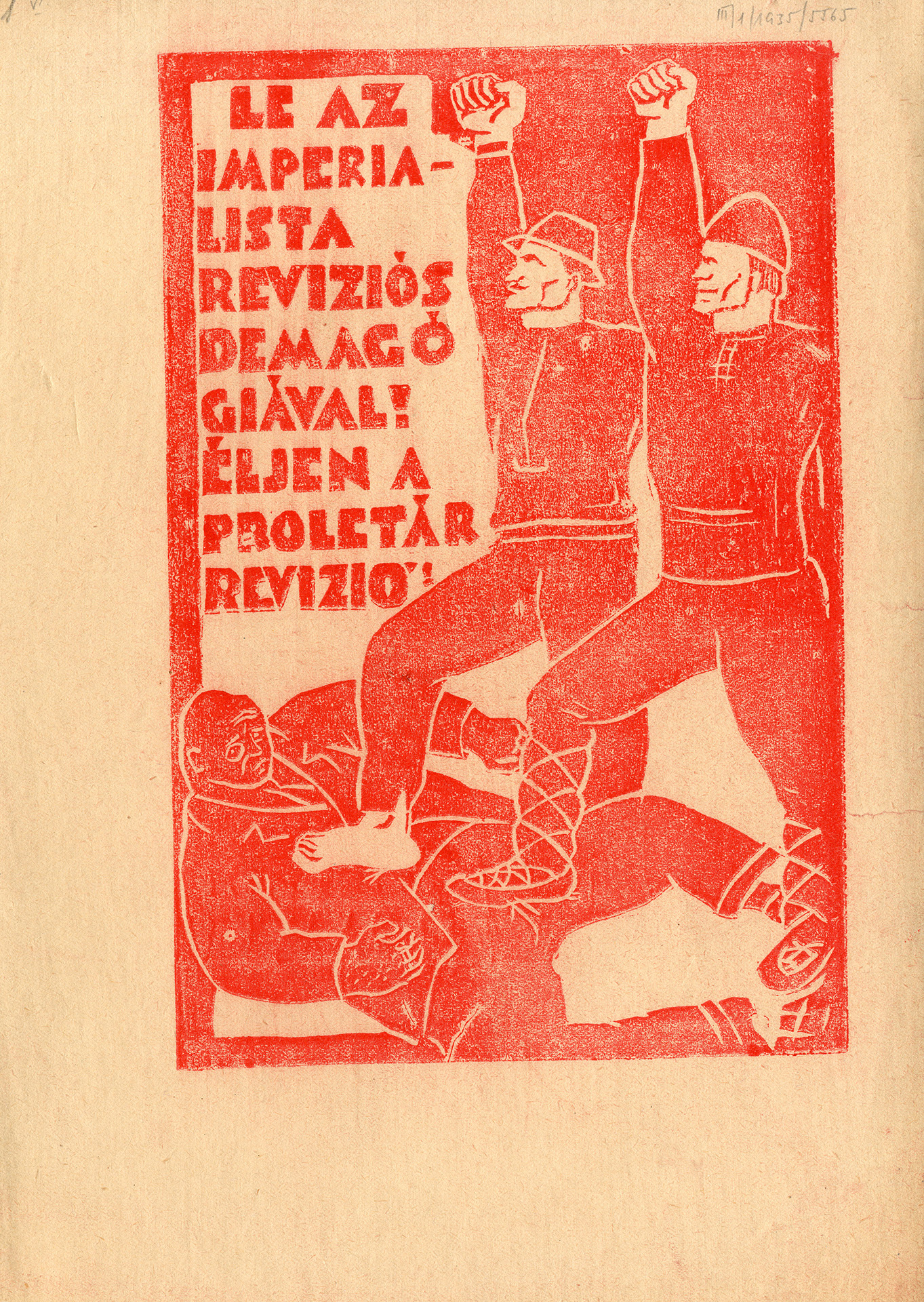

Éva Képes, Le az imperialista revíziós demagógiával! Éljen a proletár revízió! [Down with imperialist revisionist demagogy! Long live the proletarian revision!], 1935

linocut, flyer of the KMP – Party of Communists in Hungary

Institute of Social History, The Archives of Political History and Trade Unions, Budapest

Zoltán Kónya, Egészsége érdekében: Celofiltert a magyarnak [For the sake of their health, Celofilter cigarette paper for Hungarians, 1930-as évek], 1930s

design for an ad-poster, paint, pencil on paper

Budapest Poster Gallery