One might say that the intellectual prelude to the 1930s can be found in the seminal work La rebelión de las masas [The Revolt of the Masses] written by the Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset, which proves to be, with the benefit of hindsight, still very instructive. First published as a series of articles in 1929, the book defends the values of meritocratic liberalism against attacks from both communists and right-wing populists, postulating a Europe of unified nations. Ortega traces the genesis of the “mass-man”, describing the rise to power and action of the masses in society. He views the mass man as a psychological type appearing no less among physicians and artists than among managers, technocrats and unskilled workers. A new type, whose “main characteristic lies in that, feeling himself ‘common,’ he proclaims the right to be common, and refuses to accept any order superior to himself”. The mass man “ ‘did not care to give reasons or even to be right’, but […] was simply resolved to impose his opinions. That was the novelty: the right not to be right, not to be reasonable: ‘the reason of unreason.’ ” Therefore, according to Ortega, the rebellion of the masses, at its deepest essence, is illiberality, boorishness, and primitiveness coming to power.

The central thesis in The Revolt of the Masses was hardly new. Since the Reign of Terror, European intellectuals, poets, and artists have repeatedly voiced their dread of the “lower orders” obtaining power and consequently gaining a vast and vulgar influence over every aspect of life and thought. A more scientific approach to grasping this major shift—the emergence of the masses—within society was made by the French polymath, Gustave le Bon, whose 1895-book, the Psychologie des Foules [The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind] served as a guide for many populist leaders in the 20th century from Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler to Vladimir Lenin. The favorable reception of Ortega’s book in the early thirties, then, must be ascribed not to the novelty of his central thesis, but to its peculiar relevance at a critical juncture in European history. By the middle of the decade, the consequences of WWI and the Great Depression swept away the political status quo, and strong-handed leaders, who ruled “on behalf of the people”, seized power. Quite correctly, Ortega saw in these developments a monstrous threat to what remained of European civilization after the war and its frenetic aftermath. Nevertheless, many artists were drawn towards mass ideologies—some out of conviction, some out of pragmatic considerations, and many were to be bitterly disappointed. The 1930s commenced for Attila József also with a turn towards the “masses.” His 1930 poem, Tömeg [Crowd], written after a mass demonstration of workers, signaled the beginning of his rapprochement to Communism and to the Communist Party, which at the time could only operate illegally in Hungary. By the middle of the decade, however, his disenchantment with the mass movements was already clear in his poems, writings, as well as in his editorial work.

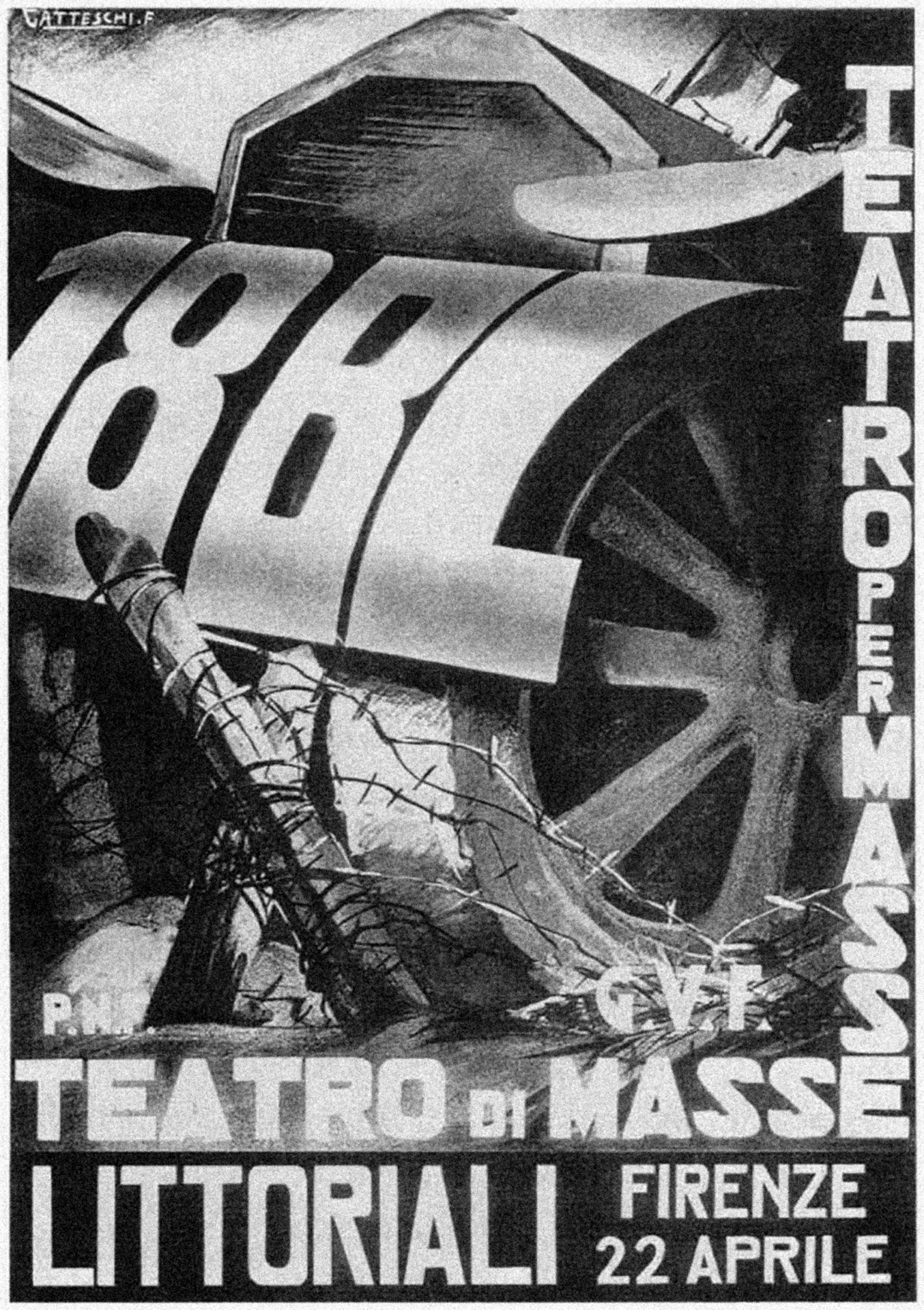

The rise of populist regimes also led to a new understanding of art and culture, where artworks were considered as part of the weaponry of propaganda and indoctrination. Considering that populism is rooted in a desire to appeal to as many people as possible, modernism—for the most part—proved to be inapplicable for this purpose, since the “general taste” was still entrenched in the 19th century. While official art under the dictatorships of Hitler and Stalin indeed turned towards the past, the general taste of the masses was more attracted by the products of contemporary popular culture—the magazines with photographs and eye-catching typography, motion pictures, the gramophone, the radio, and other forms of mass communication—than by highly-praised literary work, sculpture and painting. The channels of mass culture were used in a more effective way for propaganda than were works of art; nevertheless, the field of the arts also soon became a terrain of ideological debates, and subject to diverse political agendas. The crisis of modernism around the 1930s thus coincided with the slogans of mass ideologies that attributed political deviation to the avant-garde, solely on formal grounds. German Nazis described the modernism of the Weimar Republic as “cultural Bolshevism”; therefore national socialism was a priori hostile to the avant-garde, calling it “degenerate” (“entartete Kunst”). In the early Soviet Union, thanks to Anatoly Lunacharsky, People’s Commissar responsible for the Ministry of Education, the avant-garde was given its head, so long as artists were not actively hostile to the revolution. This changed dramatically under Stalin: from 1934 Social Realism was declared the only style suited to the state doctrine. Only Mussolini’s Italy was relatively at ease with modernism, where important branches of the local avant-garde, like the futurists, supported the fascist regime. But there too, similarly to Stalin’s Soviet Union, the avant-garde tone was soon overpowered by pompous rhetoric. Avant-garde artists under the dictatorships—even when loyal to the regime—had to endure censorship, persecution or even worse. Many left their respective countries or fell silent. Even in countries like Hungary, which we would now call a “hybrid regime”, or a “limited democracy” with authoritarian elements, artists often had to deal with heavy-handed censorship. The poet Attila József was also prosecuted several times, and his volume of poems Döntsd a tőkét! [“Chop the Roots!” or “Knock Down the Capital!”] was confiscated by the authorities.

Similarly to Ortega y Gasset, Siegfried Kracauer, the versatile German left-wing writer, journalist, sociologist and film theoretician, recognized the danger that the “mass man” and “mass culture” meant for democracy and culture. In the books he published during the period of the Weimar Republic, Ornament der Masse [The Mass Ornament, 1927] and Die Angestellten [The Salaried Masses, 1930], he observed that modern technology, as a product of the Enlightenment, is not automatically coupled with reason. For Kracauer, the entertainment industry with its revues and films was a template that could be “filled with any content”—including dangerous ones such as nationalism. While Die Angestellten was received by the democratic public as a constructive contribution to the debate, there were wild anti-Semitic attacks on the part of extreme right-wing news outlets, and it became one of the books that were publicly burnt by the National Socialists on May 10, 1933.

After Adolf Hitler became Chancellor in January 1933, the Party declared war on everything that did not fit their concept of “German Art.” In Mein Kampf, Hitler had announced early on that, in view of the “pathological excesses of insane and depraved” artists, it must be the task of the National Socialist leadership to “prevent people from being driven into the arms of spiritual madness”. Nazi theorist and ideologue Alfred Rosenberg developed this theory even further. In his book Der Mythus des 20. Jahrhunderts [The Myth of the 20th Century, 1930] Rosenberg described modern art as a problem of race: “Art is always the creation of a certain blood, and the form-bound nature of an art is only understood by creatures of the same blood.” He strictly rejected an “art in itself” that is at home all over the world. As leader of the Kampfbund für deutsche Kultur [Combat League for German Culture], founded in 1929, he agitated against abstract, experimental modernism and American cultural influences such as “nigger jazz”.

After coming to power by means of the so-called “Ermächtigungsgesetz” [Enabling Act], which gave him plenary powers, Hitler could finally declare on March 23, 1933 that: “Blood and race are once again the source of artistic intuition”. After the violent “removal” of Jewish, communist, liberal and other “undesirable” artists and thinkers from public offices in the first few months after the National Socialists came to power, it became clear that the diversity of art and culture of the Weimar Republic was irrevocably over. The avant-garde, metropolitan artistic and cultural scene was considered “alien” and “cultural Bolshevist”, and was rejected and persecuted. The Reichskulturkammer [Reich Chamber of Culture], founded on September 22, 1933, chaired by Reich Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels, was responsible for the reorganization of artistic production, monitoring the entirety of cultural life. Its central control encompassed the visual arts, architecture, film, theater, literature, music, press and radio. Anyone who was not of “Aryan” descent or was in conflict with the official NS cultural policy, was no longer allowed to practice his or her profession.

How did artists and intellectuals react to ideological influence, censorship, surveillance or even bans on work, publication and exhibitions during National Socialism? How did they try to maintain their artistic identity? Did they go into inner emigration, did they adapt, did they try to attract as little attention as possible? Or did they offer artistic resistance through “forbidden” art and literature? Did they only see the possibility of leaving the country or did they fight underground? The evaluation of the diverse answers from the German artists and intellectuals of the 1930s depends on the philosophical disposition, moral standpoint, temperament, and political conviction of today’s critics. Can we find works praising the Reich and its leader aesthetically relevant, independently of their political and cultural context? Or, the other way round: can we deem artworks criticizing and opposing the system “better,” solely on the basis of their political courage and merit? Can we separate the works from their creators? In most of the cases, we have to deal with completely individual careers, and judging them retrospectively is also a complex task. It is clear, however, that the contemporary Attila József sympathized with those who resisted the lure of mass ideology in one way or another. This sympathy is also evident in the poem he wrote on the occasion of Thomas Mann’s visit to Budapest in early 1937, when he greeted the exile author in his poem Thomas Mann üdvözlése [Welcome to Thomas Mann] as “a European mid people barbarous, white.”

Vladimir Lenin famously stated in a conversation with German Marxist theorist and activist, women’s right advocate Clara Zetkin in 1920: “Art belongs to the people. It must have its deepest roots in the broad mass of workers. It must be understood and loved by them. It must be rooted in and grow with their feelings, thoughts and desires. It must arouse and develop the artist in them.” The remark was widely replicated and could be found on the walls of almost every cultural institution throughout the Soviet Period, proclaiming that, under the rule of the Soviets, it would be the masses who defined culture. In reality, culture in the Soviet Union was defined by those who ruled in the name of the “people”: well-educated and experienced elites, who considered “art as a weapon of struggle”. Avant-garde artists heard this call, and were ready to put their creative talents at the service of the revolution. During the 1920s, thanks to Anatoly Lunacharsky, People’s Commissar responsible for the Ministry of Education, the avant-garde was given its head. Yet, artists soon had to experience that the struggles happened ever more often in the cultural field itself, and the enemy that was targeted was none other than the avant-garde. The advent of a new era in arts and culture was signaled by the death of the poet Vladimir Mayakovsky in 1930, who, similarly to Attila József, committed suicide. In his essay On a Generation that Squandered its Poets, written shortly after Mayakovsky’s death, the dead poet’s friend, linguist and literary theorist Roman Jakobson described the atmosphere of the First Five-Year Plan (1928–1932) as follows: “We are living in what is called the ’reconstruction period,’ and no doubt we will construct a great many locomotives and scientific hypotheses. But to our generation has been allotted the morose feat of building without song.”

In 1929, when Stalin established his dictatorship, all power within the cultural sphere fell into the hands of aggressive groups whose aim was to monopolize the cultural field. These organizations included the RAPP [Российская ассоциация пролетарских писателей, Russian Association of Proletarian Writers] in literature, the AKhRR [Ассоциация художников революционной России, Association of Painters of the Revolution] in painting, RAPM [Российская ассоциация пролетарских музыкантов, Russian Association of Proletarian Musicians] in music, the VOPRA [Всероссийское общество пролетарских архитекторов, All-Russian Society of Proletarian Architects] in architecture, and others. By the turn of the decade the struggle was virtually over: The cultural field was being cleaned up in preparation for the Central Committee decree of 1932. The party resolution On the Restructuring of the Literary-Artistic Organizations [О перестройке литературно-художественных организаций] on 23 April 1932 marked the beginning of a new era in Soviet cultural history. All artistic associations were dissolved, and the Union of Soviet Writers [Союз писателей СССР] was set up (after a two-year preparation, it was officially founded in 1934), which paved the way for the doctrine that became known as Socialist Realism. Soviet art criticism regarded avant-garde “formalism” as an anti-popular, bourgeois phenomenon, and the term was used to discredit artists and trends in art that did not correspond to official doctrines. While during the 1920s the classics were famously claimed to be thrown off from the ship of modernity, “Learn from the classics” became a widespread slogan during the 1930s—not only for the sake of pleasing the traditionalist tastes of the masses, but to discredit any kind of experimentalism as “individualistic” and “cosmopolitan.” In the 1930s, the avant-garde was irrevocably losing the war, but not the one it was set up to fight. State cultural bureaucracy, backed by the totalitarian law enforcement bodies, drove into exile, persecuted, silenced, and executed those who had supported their cause from the very beginning. Others were ready to adapt the new official guidelines, believing that their work would benefit the building of the country. Yet, many of these, too, fell victim to Stalin’s “Great Purge”.

The discourse around the evaluation of Socialist Realism and the cultural heritage of the early Stalinist period began around the time of the collapse of the Soviet Union. Some art historians and theoreticians regard Socialist Realism as a retrograde return to traditionalism and describe socialist realist works with the term “kitsch” and as “a lapse into barbarity”. Others characterize it as a totalitarian version of the crisis of modernism, paralleling it not only with the art of Fascist Italy or Nazi Germany, but also with French neoclassicism or American regionalism. The one point they seem to agree upon is that while Socialist Realism aimed at reaching and educating large masses, the masses themselves were more attracted to the products of popular culture than to socialist realist works, which they found didactic and devoid of entertainment value, and “divorced from real life no less completely than Malevich’s Black Square”. This also explains why the Soviet authorities could not (and did not want to) fully suppress foreign mass culture, and they also fostered the development of a Soviet mass culture. As recent studies have pointed out, entertainment played a complex role in politics, while also informing the boundaries of the political and the supposedly non-political. Mass culture proved to be a more efficient vehicle to influence the masses than “high culture”. Furthermore, the noise of the cultural war did not reach the more distant, rural regions of the country, where a large percentage of the population, despite massive literacy-campaigns, were still unable to read or write. While benefiting from the impact of industrialization and modernization that lead to an unprecedented degree of mobility within society, the “people” were more concerned with the sometimes tragic consequences of aggressive collectivization. Amidst harsh anti-religious campaigns, they were also compelled to reconcile their traditions with the new ways and language of the regime.

For a long time, the terms Fascism and Modern Art used to seem comfortingly opposed to each other. How could a political force that represented “imperfect totalitarianism,” or “a terroristic form of capitalism” be considered capable of any significant cultural production, let alone a future-oriented, modernist one? The last two decades of scholarship in history, art history, and literature have radically revised this postwar assumption. In fact, Italian Fascism was particularly full of contradictions and ambiguities. At times the cultural climate allowed dissent; unlike Nazi Germany and the 1930s Soviet Union, it even encouraged experimentation and sustained a degree of coexistence of differing attitudes. Once Fascism came to power, there emerged the question of an official state art. But despite its much-vaunted aesthetic proclivities, Fascism did not move in this direction, seemingly preferring the broader legitimation that might be gained through a policy that one historian has dubbed “aesthetic pluralism”. In 1923, Mussolini famously claimed that “I declare that it is far from my idea to encourage anything like a state art. Art belongs to the domain of the individual. The state has only one duty: not to undermine art, to provide humane conditions for artists, to encourage them from the artistic and national point of view”. Following this, the “exceptional laws” [Leggi Eccezionali] of 1926 only referred to members of the (former) Opposition, the so-called “Aventinian” deputies, like Marxist philosopher and politician Antonio Gramsci. Italian intellectuals and artists were “only” harassed and persecuted on the grounds of their political views, not of the art form or style they chose to work in.

During the 1930s, and, to a lesser extent, even after the introduction of the Racial Laws [Leggi Razziali] in 1938, Fascist Italy continued to have a pluralistic approach towards culture, largely defined by the former futurist and “enlightened” Fascist, Giuseppe Bottai, who in various capacities was the most important figure in Italian culture in the 1930s. An intelligent and cultivated man, Bottai expressed his views on culture early on. In 1927 his review Critica Fascista launched a debate on the notion of a possible fascist art, and Bottai summarized the results: with an emphasis on italianitá or “Italianness”, a Fascist art should represent the continuation of the grand Italian tradition; it should not simply imitate the styles of the past but should infuse Italy’s abiding characteristics of order, solidity, and clarity with a modern sensibility. The state should not attempt to influence individual creativity by imposing formulaic or stylistic preferences. Instead it should provide a framework that would secure the livelihood of artists while supervising the quality of production. Although Bottai’s directives afforded artists a certain creative freedom, the state’s gradual establishment of rigid formal structures ensured a covert and insidious form of control. As part of the Fascist corporative system of “syndicates”, the Federazione dei Sindicati Intelletuali (changed to Confederazione dei Professionisti e degli Artisti in 1931) incorporated organizations for writers, musicians, painters, etc. In order to work or participate in any art project organized by the regime, an artist had to register with the syndicate and be in possession of a Fascist party membership card. The level of control depended on the individuals in authority. It appears that many artists passively colluded with the regime so as to be allowed to continue their work, but many of the most gifted Italian painters, sculptors, and architects believed wholeheartedly in a Fascist culture and worked devotedly to realize it.

By 1932, when his doctrine “Dottrina del Fascismo” [The Doctrine of Fascism] was published in the Enciclopedia Italiana, Mussolini was drawing on ancient Rome as a model for his nationalistic and imperialistic aims, and the concept of romanità, the cult of ancient Rome became dominant. With himself a “condottiero-like” figure, at Italy’s helm, he envisaged a Fascist nation asserting its power and dominating the Mediterranean world. The image of the Duce as the “savior of Italy”, was primarily imposed through the propaganda machine of the Ufficio Stampa (later the Ministry of Press and Propaganda). Apart from the obvious allure of his oratory, endless photographs, films, busts, paintings, and equestrian monuments of the Duce were used to seduce the Italian people. The cult around the Duce was largely based upon theatrical forms from the very beginning. In this, Mussolini was greatly helped by the man who would become, in effect, his minister of propaganda and chief image-counselor, Giovanni Starace, appointed in December 1931. Starace conceived and organized the “oceanic” demonstrations of tens of thousands of Romans in Piazza Venezia, beneath the Duce’s speaking balcony with its hidden podium; he abolished the “insanitary” handshake in favor of the “hygenic” Roman-based Fascist salute. And he made sure that the orchestrated cheers of the crowd were directed only to Mussolini: “One man and one man alone must be allowed to dominate the news every day, and others must take pride in serving him in silence.”

The theatralization of Italian public life was followed with awe—and disgust—in many countries of Europe. In Hungary, while the Gömbös-government was busy forging close links with the Fascist dictatorship, Leftist intellectuals—like Attila József—followed the mass spectacles with growing fear. Yet, it is highly misleading to think of the Fascist movement as a product of “mass society.” On the contrary, a true mass society started to emerge only in the mid-1930s, with the growing importance of the media. Even then, Italian society remained fragmented, with vast areas of isolation and backwardness in which the messages of mass culture could be received only very faintly, if at all. The totalitarian aspiration to create a mass public, which Fascism shared, found its practical limitations in these difficulties of communication.

The German writer Thomas Mann, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1929, was forced to leave Germany after the Nazi’s came to power, first living in southern France and then in Küsnacht, Switzerland. During his career, he visited Hungary numerous times; his last visit to Hungary took place in January 1937. Organized by the literary journal Szép Szó [Beautiful Word], he gave a reading at the Hungarian Theater, where he read a chapter from Lotte in Weimar, the novel he was currently working on. As the editor of the Szép Szó, poet Attila József greeted the exiled author, who—along with several other intellectuals—at this time had already been deprived of his German citizenship.

However, Attila József was not allowed to publicly read out the poem he had written for this occasion, Thomas Mann üdvözlése [Welcome to Thomas Mann], due to a police ban. As the newspapers reported: “The Hungarian state police found that the ode was political in nature and not suitable for reading at a non-political meeting, and therefore did not allow its presentation.” The poet only learned about the police decision from the press on the day of Mann’s reading. As the daily Magyarország [Hungary] reported: “We spoke to Attila József, who said, ‘I learnt about the ban on my poem from you. It is very painful for me, because I would have been very happy to read my poem in the presence of Thomas Mann. I think it was the last line of my poem that caused the misunderstanding that led the police to ban it.’” József was therefore only able to present the work privately to Mann, in which he greeted the exiled author as “a European mid people barbarous, white.” Thomas Mann, for his part, saw a “valuable friend” in the like-minded Hungarian poet who stood on the same platform as him. It was Mann’s sixth and final visit to Hungary.

Welcome to Thomas Mann

Just as the child, by sleep already possessed,

Drops in his quiet bed, eager to rest,

But begs you: “Don’t go yet; tell me a story,”

For night this way will come less suddenly,

And his heart throbs with little anxious beats

Nor wholly understands what he entreats,

The story’s sake or that yourself be near,

So we ask you: Sit down with us; make clear

What you are used to saying; the known relate,

That you are here among us, and our state

Is yours, and that we all are here with you,

All whose concerns are worthy of man's due.

You know this well: the poet never lies,

The real is not enough; through its disguise

Tell us the truth which fills the mind with light

Because, without each other, all is night.

Through Madame Chauchat’s body Hans Castorp sees,

So train us to be our own witnesses.

Gentle your voice, no discord in that tongue;

Then tell us what is noble, what is wrong,

Lifting our hearts from mourning to desire,

We have buried Kosztolányi; cureless, dire,

The cancer on his mouth grew bitterly,

But growths more monstrous gnaw humanity.

Appalled we ask: More than what went before,

What horror has the future yet in store?

What ravening thoughts will seize us for their prey?

What poison, brewing now, eat us away?

And, if your lecture can put off that doom,

How long may you still count upon a room?

O, do not speak, and we can take heart then.

Being men by birthright, we must remain men,

And women, women, cherished for that reason.

All of us human, though such numbers lessen.

Sit down, please. Let your stirring tale be said.

We are listening to you, glad, like one in bed,

To see to-day, before that sudden night,

A European mid people barbarous, white.

January 1937

Translated by Vernon Watkins