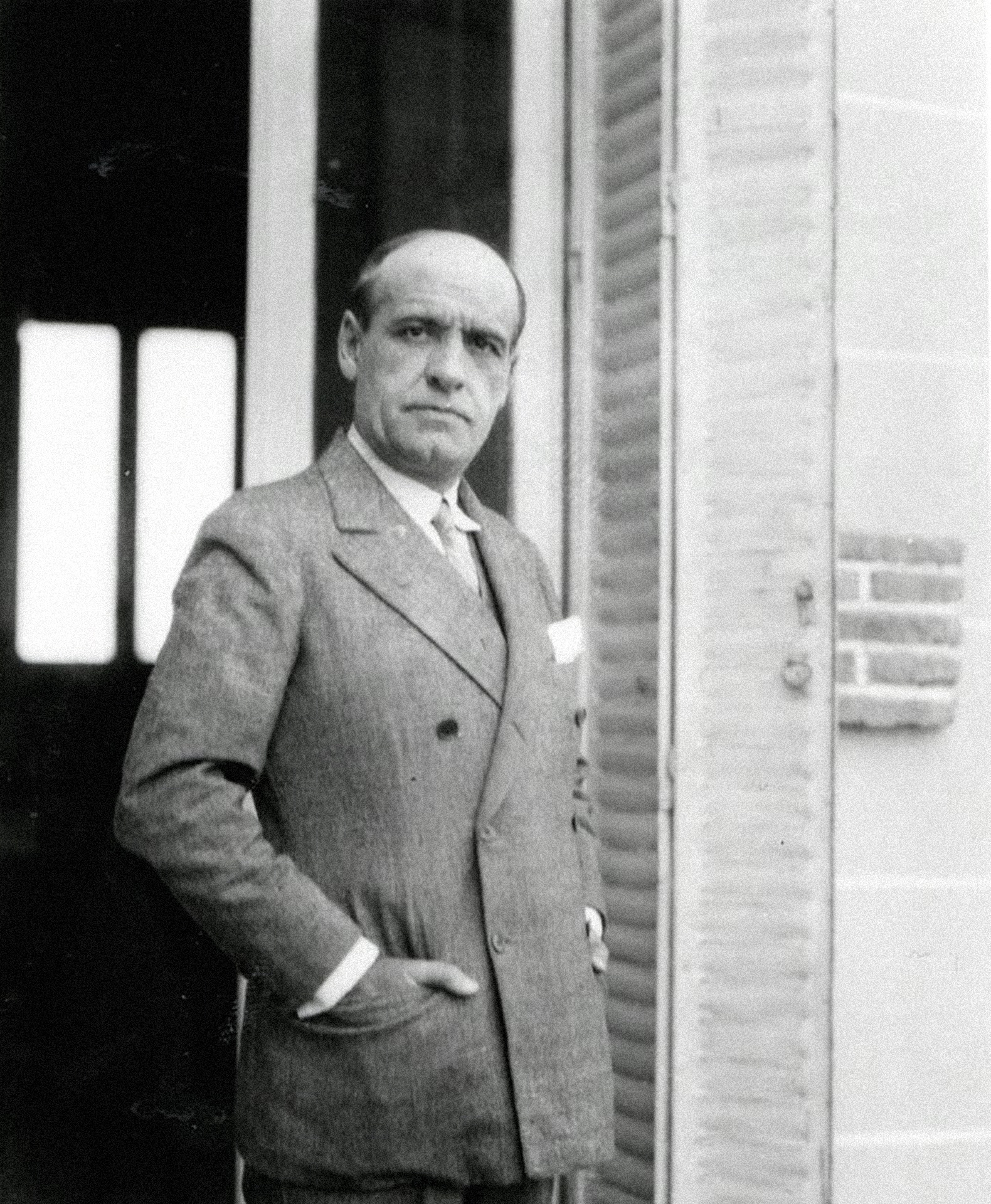

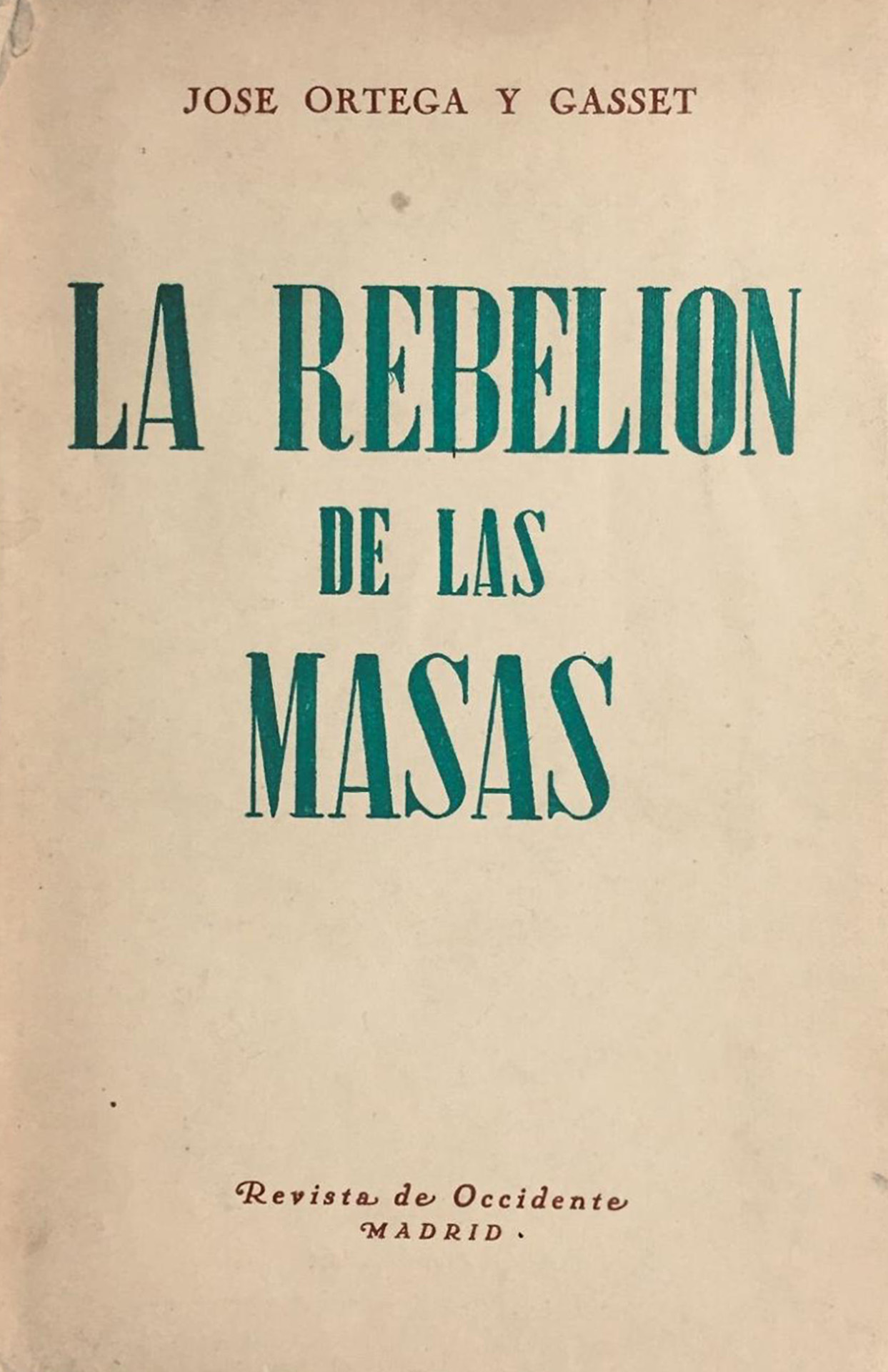

One might say that the intellectual prelude to the 1930s can be found in the seminal work La rebelión de las masas [The Revolt of the Masses] written by the Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset, which proves to be, with the benefit of hindsight, still very instructive. First published as a series of articles in 1929, the book defends the values of meritocratic liberalism against attacks from both communists and right-wing populists, postulating a Europe of unified nations. Ortega traces the genesis of the “mass-man”, describing the rise to power and action of the masses in society. He views the mass man as a psychological type appearing no less among physicians and artists than among managers, technocrats and unskilled workers. A new type, whose “main characteristic lies in that, feeling himself ‘common,’ he proclaims the right to be common, and refuses to accept any order superior to himself”. The mass man “ ‘did not care to give reasons or even to be right’, but […] was simply resolved to impose his opinions. That was the novelty: the right not to be right, not to be reasonable: ‘the reason of unreason.’ ” Therefore, according to Ortega, the rebellion of the masses, at its deepest essence, is illiberality, boorishness, and primitiveness coming to power.

The central thesis in The Revolt of the Masses was hardly new. Since the Reign of Terror, European intellectuals, poets, and artists have repeatedly voiced their dread of the “lower orders” obtaining power and consequently gaining a vast and vulgar influence over every aspect of life and thought. A more scientific approach to grasping this major shift—the emergence of the masses—within society was made by the French polymath, Gustave le Bon, whose 1895-book, the Psychologie des Foules [The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind] served as a guide for many populist leaders in the 20th century from Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler to Vladimir Lenin. The favorable reception of Ortega’s book in the early thirties, then, must be ascribed not to the novelty of his central thesis, but to its peculiar relevance at a critical juncture in European history. By the middle of the decade, the consequences of WWI and the Great Depression swept away the political status quo, and strong-handed leaders, who ruled “on behalf of the people”, seized power. Quite correctly, Ortega saw in these developments a monstrous threat to what remained of European civilization after the war and its frenetic aftermath. Nevertheless, many artists were drawn towards mass ideologies—some out of conviction, some out of pragmatic considerations, and many were to be bitterly disappointed. The 1930s commenced for Attila József also with a turn towards the “masses.” His 1930 poem, Tömeg [Crowd], written after a mass demonstration of workers, signaled the beginning of his rapprochement to Communism and to the Communist Party, which at the time could only operate illegally in Hungary. By the middle of the decade, however, his disenchantment with the mass movements was already clear in his poems, writings, as well as in his editorial work.

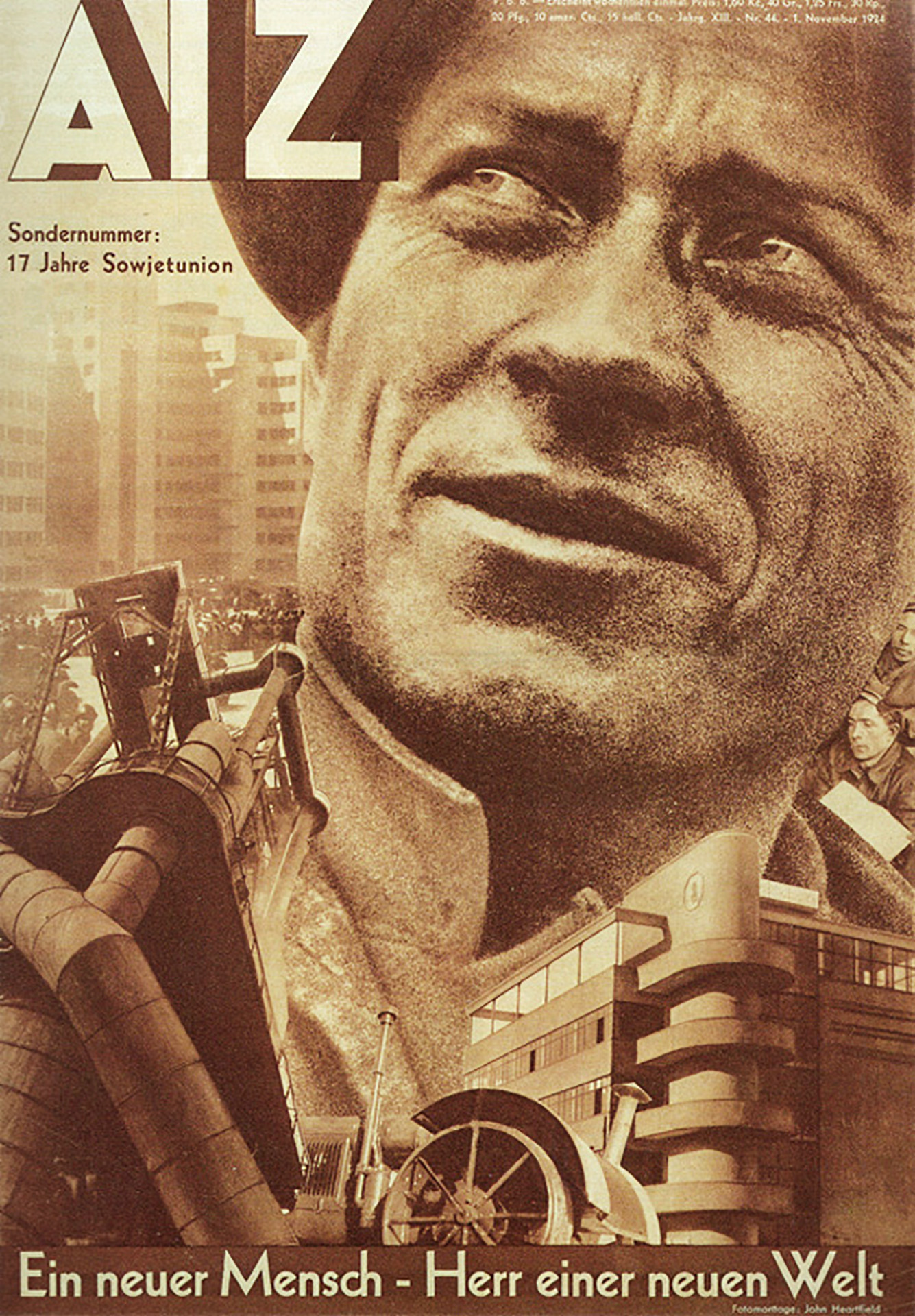

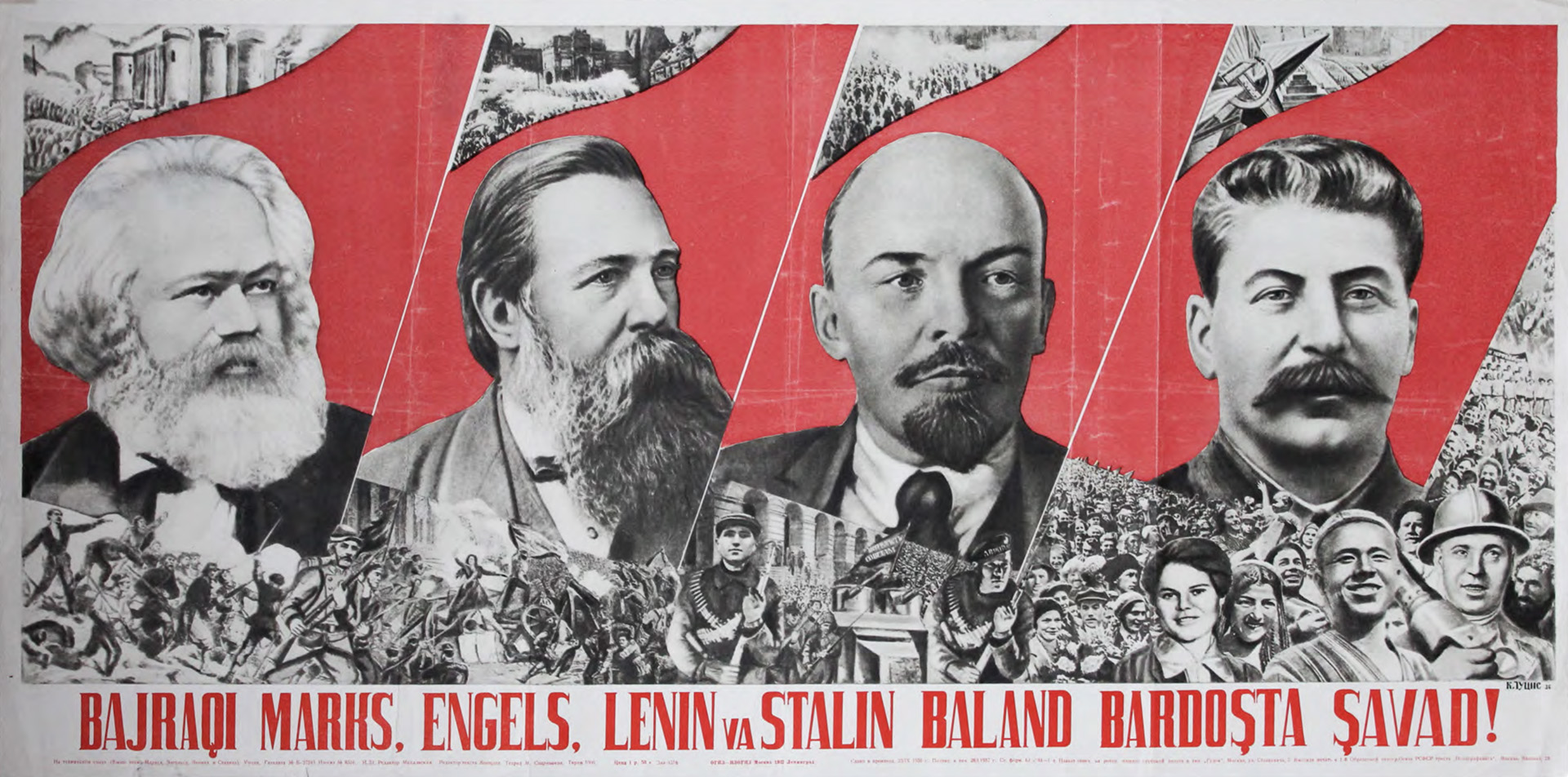

The rise of populist regimes also led to a new understanding of art and culture, where artworks were considered as part of the weaponry of propaganda and indoctrination. Considering that populism is rooted in a desire to appeal to as many people as possible, modernism—for the most part—proved to be inapplicable for this purpose, since the “general taste” was still entrenched in the 19th century. While official art under the dictatorships of Hitler and Stalin indeed turned towards the past, the general taste of the masses was more attracted by the products of contemporary popular culture—the magazines with photographs and eye-catching typography, motion pictures, the gramophone, the radio, and other forms of mass communication—than by highly-praised literary work, sculpture and painting. The channels of mass culture were used in a more effective way for propaganda than were works of art; nevertheless, the field of the arts also soon became a terrain of ideological debates, and subject to diverse political agendas. The crisis of modernism around the 1930s thus coincided with the slogans of mass ideologies that attributed political deviation to the avant-garde, solely on formal grounds. German Nazis described the modernism of the Weimar Republic as “cultural Bolshevism”; therefore national socialism was a priori hostile to the avant-garde, calling it “degenerate” (“entartete Kunst”). In the early Soviet Union, thanks to Anatoly Lunacharsky, People’s Commissar responsible for the Ministry of Education, the avant-garde was given its head, so long as artists were not actively hostile to the revolution. This changed dramatically under Stalin: from 1934 Social Realism was declared the only style suited to the state doctrine. Only Mussolini’s Italy was relatively at ease with modernism, where important branches of the local avant-garde, like the futurists, supported the fascist regime. But there too, similarly to Stalin’s Soviet Union, the avant-garde tone was soon overpowered by pompous rhetoric. Avant-garde artists under the dictatorships—even when loyal to the regime—had to endure censorship, persecution or even worse. Many left their respective countries or fell silent. Even in countries like Hungary, which we would now call a “hybrid regime”, or a “limited democracy” with authoritarian elements, artists often had to deal with heavy-handed censorship. The poet Attila József was also prosecuted several times, and his volume of poems Döntsd a tőkét! [“Chop the Roots!” or “Knock Down the Capital!”] was confiscated by the authorities.

José Ortega y Gasset in Aravaca, 1929

bw. photo, exhibition print

Universidadrey Juan Carlos, Madrid

José Ortega y Gasset, La rebelión de las masas [The Revolt of theMasses], 1930

Madrid: Revista de Occidente, 1930

private collection

First published as a series of articles in the newspaper El Sol in 1929, and as a book in 1930. The English translation, first published two years later, was authorized by Ortega.

Heinrich Hoffmann, Hitler and Mussolini in front of Josef Thorak’s sculpture Kameradschaft [Comradeship], Berlin, 1937

bw. photo, exhibition print

[Mussolini erlebt Deutschland (Mussolini experiences Germany), ein Bildbuch von Heinrich Hoffmann, mit einem Vorwort von Otto Diedrich, Pressechef, München: Heinrich Hoffmann Verlag, 1937, 43]

John Heartfield [Helmut Herzfeld], Ein neuer Mensch – Herr einer neuen Welt, [The New Man – Master of a New World], 1934

Cover of AIZ – Arbeiter Illustrierte Zeitung (Prague), Vol. XIII, No. 44, November 1, 1934

(Special edition: “17 years of the Soviet Union”)

photomontage, exhibition print

© 2019 Heartfield Community of Heirs. All Rights Reserved

https://www.johnheartfield.com/John-Heartfield-Exhibition

Gustav Klutsis, Выше знамя Маркса, Энгель’са, Ленина и Сталина! [Raise Higher the Banner of Marx, Engels, Lenin, and Stalin!], 1936

poster, exhibition print

Russian State Library, Moscow