Vladimir Lenin famously stated in a conversation with German Marxist theorist and activist, women’s right advocate Clara Zetkin in 1920: “Art belongs to the people. It must have its deepest roots in the broad mass of workers. It must be understood and loved by them. It must be rooted in and grow with their feelings, thoughts and desires. It must arouse and develop the artist in them.” The remark was widely replicated and could be found on the walls of almost every cultural institution throughout the Soviet Period, proclaiming that, under the rule of the Soviets, it would be the masses who defined culture. In reality, culture in the Soviet Union was defined by those who ruled in the name of the “people”: well-educated and experienced elites, who considered “art as a weapon of struggle”. Avant-garde artists heard this call, and were ready to put their creative talents at the service of the revolution. During the 1920s, thanks to Anatoly Lunacharsky, People’s Commissar responsible for the Ministry of Education, the avant-garde was given its head. Yet, artists soon had to experience that the struggles happened ever more often in the cultural field itself, and the enemy that was targeted was none other than the avant-garde. The advent of a new era in arts and culture was signaled by the death of the poet Vladimir Mayakovsky in 1930, who, similarly to Attila József, committed suicide. In his essay On a Generation that Squandered its Poets, written shortly after Mayakovsky’s death, the dead poet’s friend, linguist and literary theorist Roman Jakobson described the atmosphere of the First Five-Year Plan (1928–1932) as follows: “We are living in what is called the ’reconstruction period,’ and no doubt we will construct a great many locomotives and scientific hypotheses. But to our generation has been allotted the morose feat of building without song.”

In 1929, when Stalin established his dictatorship, all power within the cultural sphere fell into the hands of aggressive groups whose aim was to monopolize the cultural field. These organizations included the RAPP [Российская ассоциация пролетарских писателей, Russian Association of Proletarian Writers] in literature, the AKhRR [Ассоциация художников революционной России, Association of Painters of the Revolution] in painting, RAPM [Российская ассоциация пролетарских музыкантов, Russian Association of Proletarian Musicians] in music, the VOPRA [Всероссийское общество пролетарских архитекторов, All-Russian Society of Proletarian Architects] in architecture, and others. By the turn of the decade the struggle was virtually over: The cultural field was being cleaned up in preparation for the Central Committee decree of 1932. The party resolution On the Restructuring of the Literary-Artistic Organizations [О перестройке литературно-художественных организаций] on 23 April 1932 marked the beginning of a new era in Soviet cultural history. All artistic associations were dissolved, and the Union of Soviet Writers [Союз писателей СССР] was set up (after a two-year preparation, it was officially founded in 1934), which paved the way for the doctrine that became known as Socialist Realism. Soviet art criticism regarded avant-garde “formalism” as an anti-popular, bourgeois phenomenon, and the term was used to discredit artists and trends in art that did not correspond to official doctrines. While during the 1920s the classics were famously claimed to be thrown off from the ship of modernity, “Learn from the classics” became a widespread slogan during the 1930s—not only for the sake of pleasing the traditionalist tastes of the masses, but to discredit any kind of experimentalism as “individualistic” and “cosmopolitan.” In the 1930s, the avant-garde was irrevocably losing the war, but not the one it was set up to fight. State cultural bureaucracy, backed by the totalitarian law enforcement bodies, drove into exile, persecuted, silenced, and executed those who had supported their cause from the very beginning. Others were ready to adapt the new official guidelines, believing that their work would benefit the building of the country. Yet, many of these, too, fell victim to Stalin’s “Great Purge”.

The discourse around the evaluation of Socialist Realism and the cultural heritage of the early Stalinist period began around the time of the collapse of the Soviet Union. Some art historians and theoreticians regard Socialist Realism as a retrograde return to traditionalism and describe socialist realist works with the term “kitsch” and as “a lapse into barbarity”. Others characterize it as a totalitarian version of the crisis of modernism, paralleling it not only with the art of Fascist Italy or Nazi Germany, but also with French neoclassicism or American regionalism. The one point they seem to agree upon is that while Socialist Realism aimed at reaching and educating large masses, the masses themselves were more attracted to the products of popular culture than to socialist realist works, which they found didactic and devoid of entertainment value, and “divorced from real life no less completely than Malevich’s Black Square”. This also explains why the Soviet authorities could not (and did not want to) fully suppress foreign mass culture, and they also fostered the development of a Soviet mass culture. As recent studies have pointed out, entertainment played a complex role in politics, while also informing the boundaries of the political and the supposedly non-political. Mass culture proved to be a more efficient vehicle to influence the masses than “high culture”. Furthermore, the noise of the cultural war did not reach the more distant, rural regions of the country, where a large percentage of the population, despite massive literacy-campaigns, were still unable to read or write. While benefiting from the impact of industrialization and modernization that lead to an unprecedented degree of mobility within society, the “people” were more concerned with the sometimes tragic consequences of aggressive collectivization. Amidst harsh anti-religious campaigns, they were also compelled to reconcile their traditions with the new ways and language of the regime.

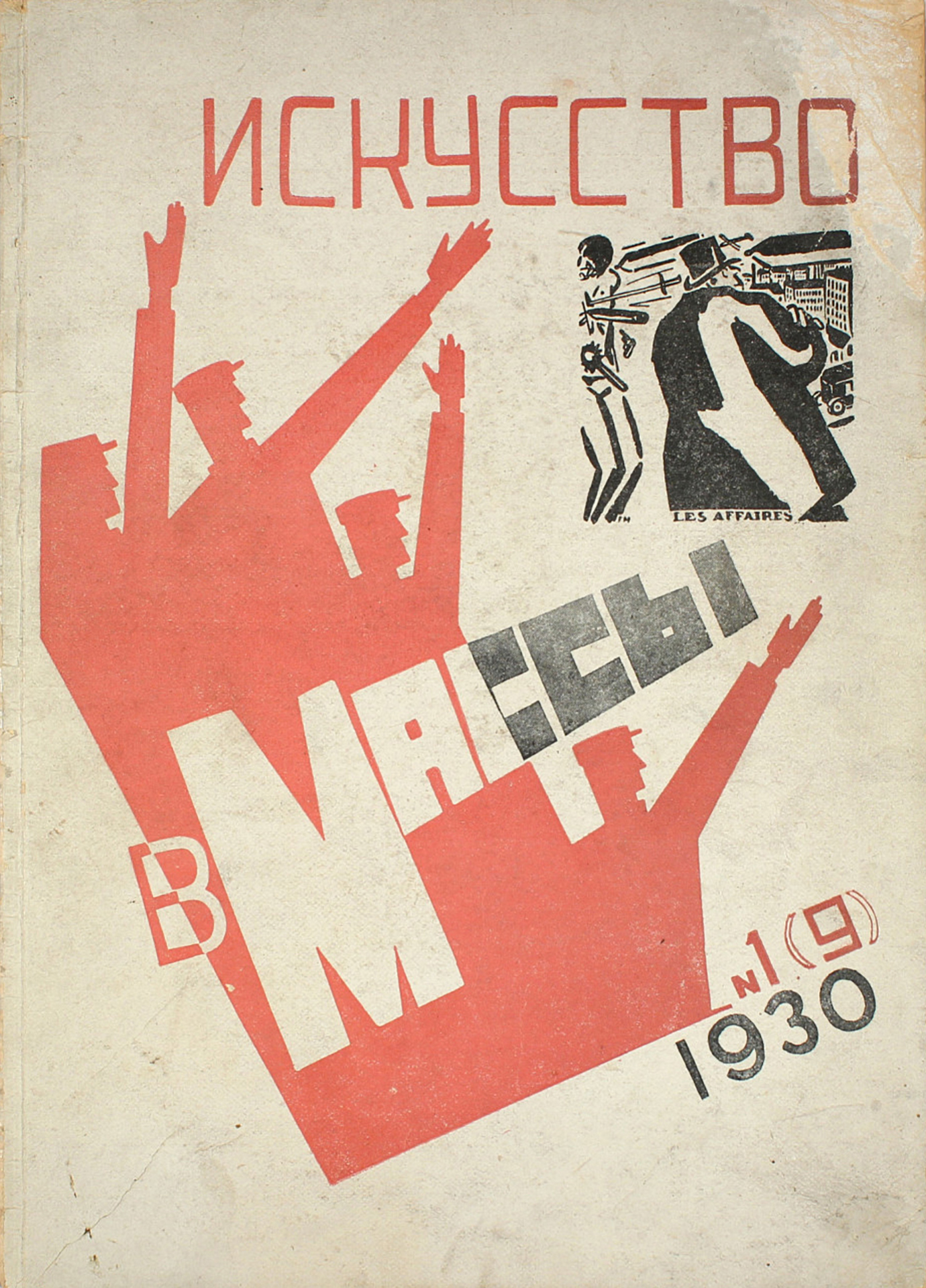

Искусство в массы [Art to the Masses], the journal of the AKhRR, Issue 1 (9): January, 1930

cover by Mariya Raiskaya

magazine cover, exhibition print

Internet Archive

Clara Zetkin at the 3rd World Congress of the Comintern, Moscow, 1921

bw. photo, exhibition print

wikimedia commons

Aleksandr Deineka, Донбасс. Обеденный перерыв [Lunchbreak in the Donbass], 1935

oil on canvas, exhibition print

Latvian State Museum, Riga

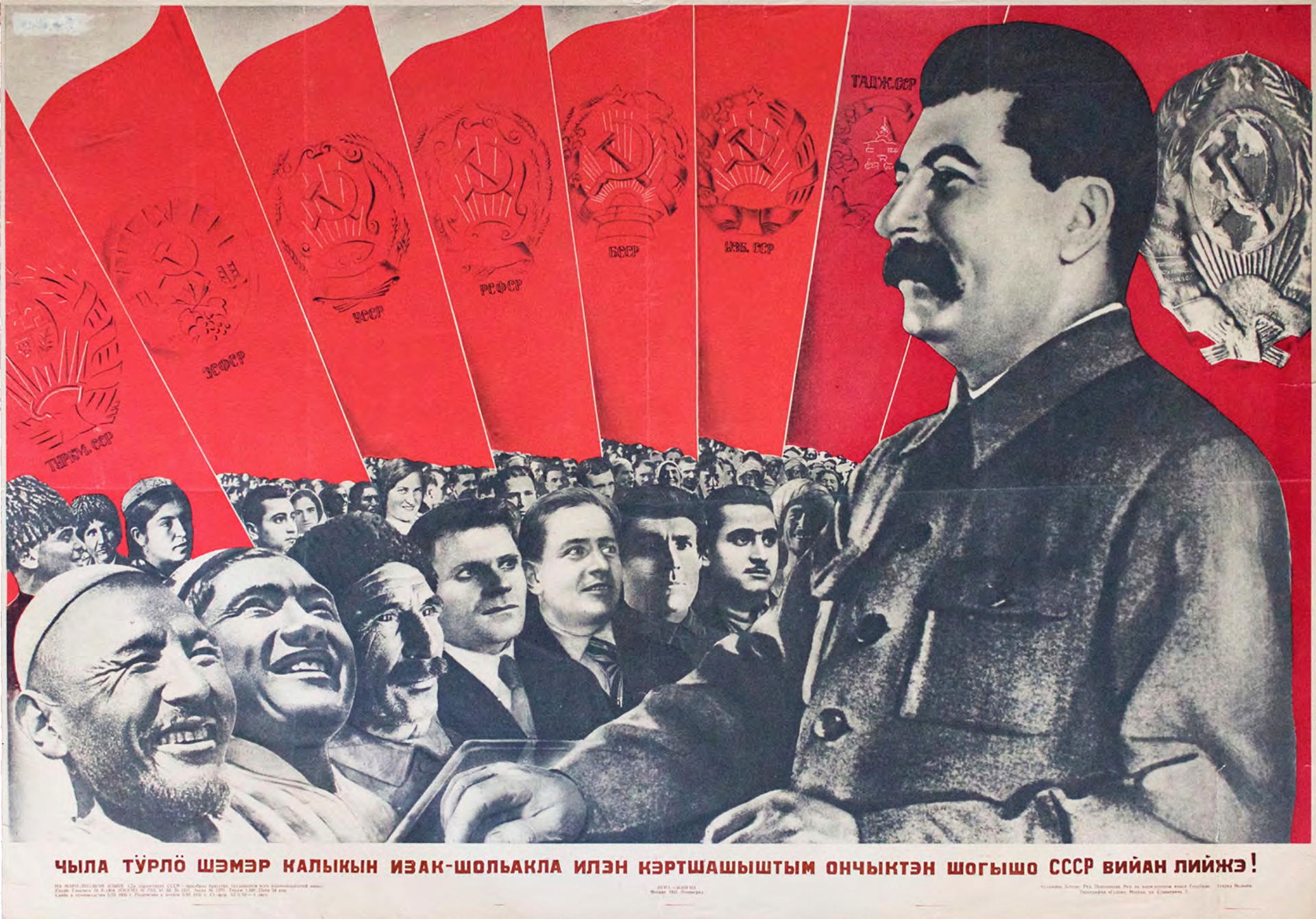

Gustav Klutsis, Да здравствует СССР — прообраз братства трудящихся всех национальностей мира! [The Model of Brotherhood among the Workers of Every Nation in the World!], 1935

poster, exhibition print

Russian State Library, Moscow

Vladimir Mayakovsky [Владимир Владимирович Маяковский], Soviet poet and a leading figure of the Russian branch of futurism, was—like many fellow avant-garde artists of his generation—an enthusiastic supporter of the cause of the Revolution. He wrote texts, designed satirical and agitprop posters for the Russian news agency ROSTA [Российское телеграфное агентство, Russian Telegraph Agency], became a member of the RAPP in 1928, and called his work Communist Futurism (комфут). He also propagandized the achievements of Soviet Russia abroad: he gave lectures in Germany, France and went on a lecture tour to the USA in 1925. His activism as a propaganda agitator found little support among his contemporaries, who—like his friend Boris Pasternak—often disapproved of his involvement with state propaganda. Towards the end of the 1920s, Mayakovsky criticized some developments in Soviet society, especially the increasing bureaucracy, which coincided with the fact that experimental art was no longer welcomed by the regime. In February 1930 he opened his exhibition 20 лет работы [Twenty Years of Work], which was intended not only to prove his revolutionary credentials to the Party, but also to present how much his work was understood and appreciated by the masses: letters from satisfied and engaged readers from all over the country served as evidence. However, the exhibition, shown in Moscow and Leningrad, received little appreciation from either the press or the Party, and further criticism of his work was published. Illness and disappointment in private life, criticism and pressure from the literary functionaries shaped Mayakoysky’s last months. On April 14, 1930, he shot himself in the heart with a pistol. The official funeral commission was headed by the managing director of the Soviet state publishers, Artemy Shalatov, who had shortly before subjected Mayakovsky to censorship. After his death, Mayakovsky’s name disappeared from public view. He was rehabilitated in 1934, after Stalin approved the publication of his collected works, describing him as “the best and the most talented poet of our Soviet epoch”. He became the greatest Communist poet despite of the fact that he was a party member for only a year, before the revolution.

Mayakovsky at his exhibition 20 лет работы [Twenty Years of Work], January 1930

bw. photo, exhibition print

wikimedia commons

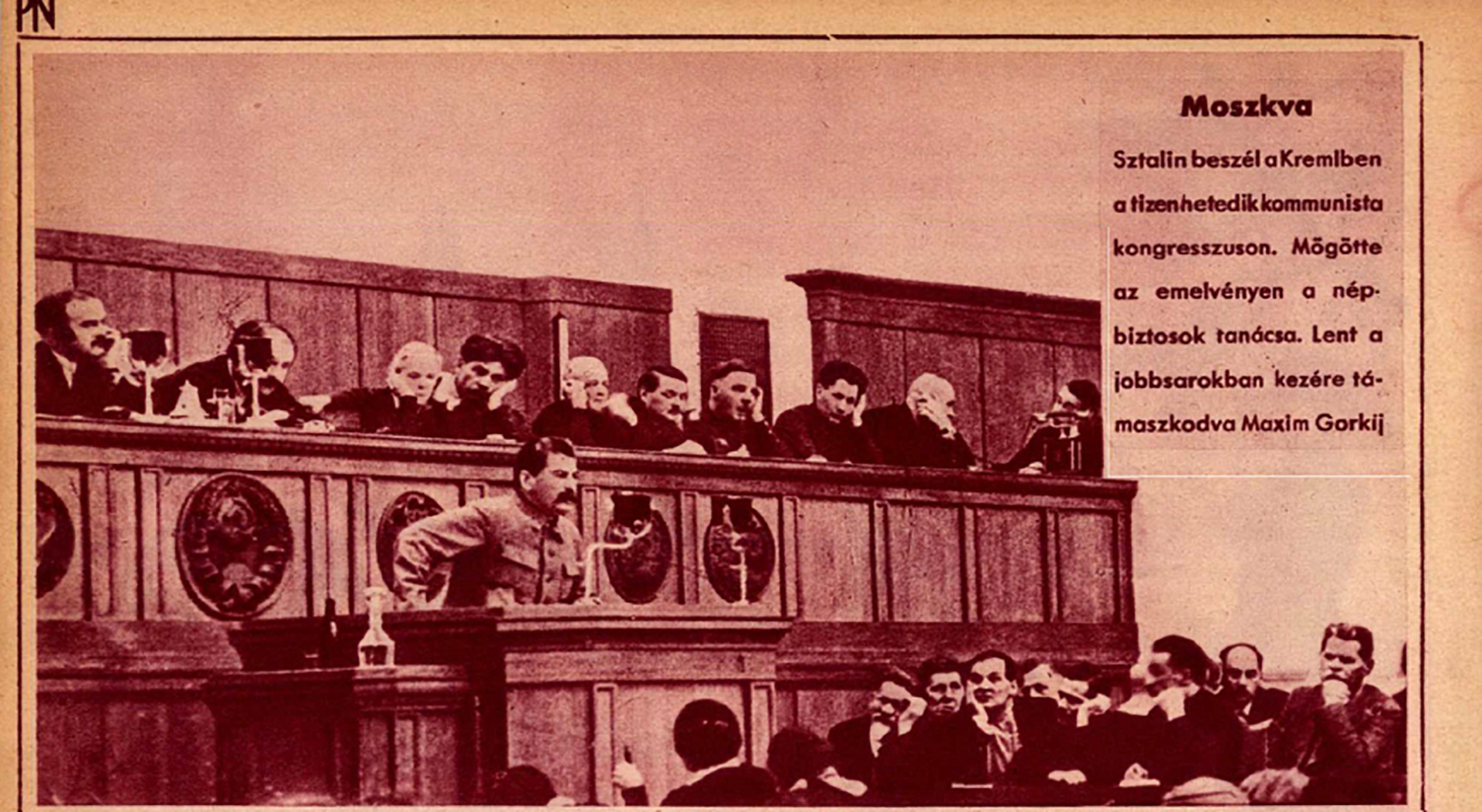

The 17th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party, held between January 26 and February 10, 1934, was labeled as the “congress of the victors” by contemporaries and by Party historians alike. Indeed, the path leading to the congress was paved by a number of factional struggles and battles within the Party. This was the first such gathering since 1930, and in the intervening three-and-a-half years the more extreme advocates of proletarianization of the arts and professions had been curbed, and former Oppositionists within the Party had acknowledged their sins and, at the congress, heaped praise on Stalin. The delegates were participating in an unprecedented cult event, the embodiment of victorious Stalinism. The 17th Congress was intended to celebrate and retrospectively ideologize the fulfillment of the First Five-Year Plan: the relentless collectivization of agriculture—including the liquidation of the kulaks—and the rapid growth of heavy industry. The delegates at the conference, after relentlessly and uncritically supporting Stalin throughout the internal Party struggles, could feel sure of themselves, if only for a short while. Most of the victors were unable to enjoy the light of Stalinist glory for long: the Great Purge eliminated not only the defeated, but the victors themselves. Over the next four years, 1108 of the 1966 delegates were arrested and either disappeared into the Gulag or were executed.

Stalin giving a speech at the 17th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party, with Maxim Gorky in the lower right corner, 1934

exhibition print

Pesti Napló Képes Melléklete [Illustrated Supplement of Pesti Napló], February 18, 1934 / Arcanum

The Union of Soviet Writers was chaired by Maxim Gorky [Максим Горький], the once prodigal son. His return from his second exile was a major propaganda victory for the Soviets: he was decorated with the Order of Lenin; the city of Nizhni Novgorod and the surrounding province were renamed Gorky as well as Moscow’s main park, and one of the central Moscow streets, Tverskaya, were renamed in his honor, as was the Moscow Art Theatre. Gorky became a loyal supporter of Stalinism, yet he hoped that the time of consolidation had arrived and that the writers’ union could be an intellectual organization that was loyal to the power and the revolution, but could remain relatively independent. In his view, the Union was to allow greater unity of creative vision and a harmony between the individual’s creative aims and the overall “creative working energies of the country.” The thrust of the Comintern’s cultural policy at this time was to gather around itself the Comintern leading writers and intellectuals in all countries on the basis of a distinct anti-fascist line. Accordingly, the Writers’ Congress, convened on August 8, 1934 and presided over by Gorky, had to demonstrate its openness to Western democracies, and manifest its humanistic values. Apart from stars of Soviet literature—like Konstantin Fedin, Mikhail Sholokhov, Aleksey Tolstoy, Aleksandr Fadeev, Boris Pasternak, Isaak Babel, and Ilya Ehrenburg—the majority of the participants were therefore not proletarian writers, but anti-fascist bourgeois writers from all over the world, sympathetic to the Soviet Union. The congress was attended by 591 delegates from 52 countries—among them André Malraux, Ernst Toller and Jean-Richard Bloch. From Hungary it was not Attila József, the bona fide “proletarian poet,” who was sent as a delegate but Gyula Illyés and Lajos Nagy, who were never affiliated with the Party. It was to the international delegates that a leaflet written by a group of anonymous Russian writers was addressed. It outlined the “supreme lie” that was both the congress and the Soviet Union and lamented the fact that there had been a total lack of free speech in the country for almost two decades. “The USSR's network of informers is so comprehensive that even at home we often avoid speaking our minds.” The scandal was completely hushed up by the NKVD. The congress was also a major milestone in the formation of the doctrine of Socialist Realism, as well as a sign of a new era of totalitarian culture.

According to Communist lore, the term “Socialist Realism” was first used in May 1932 during preparatory discussions to set up the Soviet Writers’ Union. Accounts differ on precisely when, where, and by whom it was coined, but it was soon credited to Stalin himself. The term was first used in public by Ivan Gronsky, a high official of the organizing committee of the Union, in Literaturnaya Gazeta [Литературная Газета] on May 23, 1932. Maxim Gorky published his essay О социалистическом реализме [Socialist Realism] in 1933, but the final theoretical framework of the term was set up by the 1934 First Congress of Soviet Writers. Andrei Zhdanov, as Party representative, who would preside over Soviet culture for the next fourteen years, made the keynote address, in which he referred explicitly to Gorky’s work, describing the young Soviet literature as the “most imaginative, most progressive and most revolutionary” in the world, because it depicted life not as “objective reality, but rather as reality in its revolutionary development.” Gorky himself described the “new Soviet man” that literature should portray: “A new type of man is springing up in the Soviet Union. He possesses faith in the organizing power of reason. … He is conscious of being the builder of a new world, and although his conditions of life are still arduous, he knows that it is his aim and the purpose of his rational will to create different conditions and he has no grounds for pessimism.” Socialist Realism is thus characterized by the glorified depiction of Communist values, such as the emancipation of the proletariat, with realistic imagery. Because Socialist Realism was a method of creation rather than a style or an aesthetic system, its theorists concentrated on abstract political definitions that all arts had to reflect and through which their success or failure could be judged. These were народность [‘people’ or ‘nation’], which was centered around the relationship of the work to popular sentiments as well as to the ethnic origins of the people depicted; классовость [class] related to the class awareness of the artists and the subjects they depicted; партийность [the relationship with the Party] was the expression of the leading role of the Communist Party in all aspects of Soviet life as well as membership of the Party; and идейность [ideology], which was to be the main component of the artworks, approved by the Party. Zhdanov emphasized—to the dismay of many of the delegates—that Socialist Realism was the official style of Soviet culture, and he decreed that all artists, were to be “engineers of the human soul.” Thus, culture was successfully co-opted by the state doctrine. Originally, the congress was supposed to take place every three years, but it was postponed many times, and the next event was in 1954, after Stalin’s death. This was no coincidence: one congress was enough for Stalin to achieve his goal of bringing writers to heel. A third of the original delegates perished in the 20 years between the first and second congresses. Some died from natural causes, and others were killed during the war. However, the overwhelming majority were executed or died in prison or labor camps.

Andrei Zhdanov and Maxim Gorky on the First Congress of Soviet Writers in August 1934

bw. photo, exhibition print

Süddeutsche Zeitung Photo / Alamy

Surprisingly, the spread of the cult of the Soviet Union coincided with the culmination of Stalin’s terror. The task of the invited Western intellectuals was to refute rumors of the terror and to certify that the long-awaited miracle was coming to fruition or had already been fulfilled in the state of the workers. In 1933, at a time of famine in Ukraine, which claimed six million lives, George Bernard Shaw made a straightforward statement that he had never seen such abundance and prosperity before visiting Ukraine—since his visit was orchestrated in a way that he was not allowed to see what was really going on in the country. In 1935, Romain Rolland, who served as an unofficial ambassador of French artists to the Soviet Union, drew a picture of the humanist, “enlightened Bolshevik ruler” based on a private conversation with Stalin. (Although he admired Stalin, he attempted to intervene against the persecution of his friends.) Less successful—at least, for the Stalinist regime—proved to be the visit by André Gide. Gide’s “conversion” in 1932 and his enthusiastic agitprop work was a huge sensation, and the Stalinist regime soon recognized the propaganda-potential of having such a celebrated Western literary figure on their side. Gide was at first reluctant to accept the official invitation of the Soviet Writers’ Union, and decided to travel only at the repeated request of the then very ill Gorky. By the time he arrived in the summer of 1936, Gorky was dead. Gide arrived in Moscow as a believer and appeared to be ready to honestly play the role assigned to him. But he soon had to experience the surveillance and control that even foreign intellectuals had to endure in the Soviet Union. In spite of the Soviets’ efforts, instead of the expected testimony, Gide eventually wrote a highly critical book entitled Retour de l’U.R.S.S. [Return from the Soviet Union]. As fellow critics noted, “Gide left as a fellow-traveler and returned home with a Stalin-Hitler analogy.”

Maxim Gorky sees off Romain Rolland, who is leaving Moscow after an official visit, August 1935

bw. photo, exhibition print

SPUTNIK / Alamy

Among the delegates at the First Congress of Soviet Writers were two Hungarians: Gyula Illyés and Lajos Nagy. The Soviet Union and Hungary did not establish diplomatic relations until the beginning of February 1934, so it was through informal channels that the two writers received a visa. Attila József was desperate to hear that it was not him, the committed leftist, who was granted this opportunity. The choice might have been the result of the intrigues of Hungarian literary immigrants living in Moscow (Antal Hidas and Sándor Gergely), but as recent studies show, it was mainly because the Soviet organizers wanted to invite intellectuals to Moscow who were not (yet) committed to their cause. Illyés and Nagy both had left-wing contacts, but were never members of the then illegal Communist Party of Hungary (KMP), which made them ideal candidates. As a gift from the Soviet Writers’ Union, foreign writers who arrived there were able to travel ten thousand kilometers in the Soviet Union for weeks before the Congress. This is how Illyés got to Leningrad, the Azov Sea region, Kharkov, and Nizhny Novgorod, but, unlike Nagy, in the end he was unable to attend the congress as he had to return to Budapest before it started. After his return, his experiences in the Soviet Union were published in the form of a travel diary, first in the daily newspaper Magyarország [Hungary], and in the prestigious literary journal Nyugat [West] (where a chapter was published), and also in book format. In describing Soviet reality, Illyés tried to balance praise and criticism. On the one hand, he expressed his appreciation of the social mobilization and grandiose constructions that began after the revolutions of 1917, and on the other hand, he warned against the over-idealization and uncritical acceptance of the Soviet system.

Gyula Illyés in Moscow, 1934

bw. photo, exhibition print

Petőfi Literary Museum, Budapest

After the turbulent years of the “Cultural Revolution”, Soviet culture entered as somewhat “lighter” period. The militant Communist cultural organizations (such as RAPP, AKhRR, or RAPM) that had terrorized “bourgeois” artists had been dissolved in 1932, and the oppressive censorship they had imposed had been eased. “Socialist Realism”, which had replaced the threatening demand for proletarian hegemony in culture, was—at the beginning—not a dogmatic orthodoxy and would not be used punitively or for the purposes of exclusion. It was intended rather as an umbrella large enough to cover a variety of schools and trends. This changed dramatically in January 1936 when the so-called “Campaign against Formalism and Naturalism” [Кампания борьбы против натурализма и формализма] was launched. On December 16, 1935 the Politburo passed a resolution “On the Organization of an All-Union Committee on Arts Affairs” [Комитет по делам искусств], which stipulated that it must be organized “under the USSR Sovnarkom [Council of People's Commissars], investing it with the leadership of all artistic affairs and subordinating to it the theaters, film organizations, and music, painting, sculpture, and other institutions,” including “the main administration of the film and photography industry.” Now a single body governed not just a particular branch of the arts, but all the arts. This prepared the first steps towards the campaign which started with the attack on Dmitri Shostakovich [Дмитрий Дмитриевич Шостакович] in January 1936. On 26 January, Stalin visited the Opera to hear Леди Макбет Мценского уезда [Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District] by Shostakovich, which was written in 1932 and premiered in 1934 and was praised as “the best Soviet work, the chef-d’oeuvre of Soviet creativity.” Stalin and his entourage left without speaking to anyone. Two days later, disaster struck in the form of an editorial in Pravda attacking Shostakovich’s opera. The unsigned editorial in the central Party newspaper, reputedly written by Andrei Zhdanov, was entitled “Muddle Instead of Music.” This opera, the editorial noted, had been highly praised, but it turned out to be an avant-garde monstrosity.” The anti-formalist campaign was conducted under the sign of an art that should be “simple”, accessible to the broad masses. It caused irrevocable damage to the Soviet art community, and many world-renowned artists were among its victims. The anti-formalist campaign was focused on the “remnants of modernism.” In 1936, the leaders of international modernist art: figures like Shostakovich, Sergei Eisenstein, and Vsevolod Meyerhold, as well as hundreds of lesser-known Soviet artists, architects, and musicians, were vilified as “formalists” and “naturalists” in the course of a campaign that was intended to discredit and defame so-called “bourgeois” art in the USSR.

Poster for the premiere of the opera Леди Макбет Мценского уезда [Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District] by Dmitri Shostakovich, 1934

poster, exhibition print

Lebrecht Music & Arts / Alamy

Celebrated Soviet writer Isaac Babel [Исаак Эммануилович Бабель] was on the Auditing Committee of the First Congress of Soviet Writers, during which he obliquely criticized the cult of Stalin. Speaking about his modest output, Babel ironically noted that he was becoming “the master of a new literary genre, the genre of silence.” He added that he was grateful to the Soviet establishment for being able to enjoy the high status of a writer despite his “silence,” which, in the West, would have forced him to abandon writing to “sell haberdashery.” After hearing the lengthy—and quite threatening—speech by Andrei Zhdanov, Babel felt that the congress was a “requiem for literature.” He tried to remain in the shadows, especially after the assassination of Stalin’s rival, Sergei Kirov in December 1934, and the beginning of the Great Purge. He increasingly withdrew from public life but was dispatched, at the insistence of André Malraux and André Gide, to the antifascist International Congress of Writers for the Defense of Culture in Paris in the summer of 1935, as part of the Soviet delegation. This would have been his last chance to remain in Europe, and join his family who had been living in Paris since the mid-1920s. Returning home, he remained productive, even if, during the campaign against “formalism,” he was publicly denounced for low productivity. He was working on film scripts (he collaborated, for instance, with Sergei Eisenstein on the film Bezhin Meadow [Бежин луг]). He also finished his second play, Мария [Maria], in 1935. Though set in the time of the Civil War, the play candidly alluded to current problems within Soviet society, such as political corruption, prosecution of the innocent, and black marketeering. Noting the play’s implicit rejection of Socialist Realism, Maxim Gorky accused his friend of having a “Baudelairean predilection for rotting meat.” Gorky further warned his friend that “political inferences” would be made “that will be personally harmful” to Babel. Although intended to be performed by Moscow’s Vakhtangov Theatre in 1935, the premiere of Maria was cancelled by the NKVD [НКВД, Народный комиссариат внутренних дел, People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs] during rehearsals. Four years later, Isaac Babel was arrested, tortured, and shot as part of Joseph Stalin’s Great Purge. His surviving manuscripts were confiscated by the NKVD and destroyed. As a result, Maria was never performed in Russia until after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Babel was rehabilitated during the Khrushchev Thaw in 1954.

The NKVD photo of Isaac Babel taken after his arrest, 1939

bw. photo, exhibition print

wikimedia commons

Poet Anna Akhmatova [Анна Андреeевна Ахматова] soon had to experience the unfriendly face of Bolshevism: her former first husband, the poet Nikolay Gumilyov [Николай Степанович Гумилёв] was executed for his alleged role in a monarchist anti-Bolshevik conspiracy in August 1921. Although they were divorced at this time, she was still associated with him. Her poems were deemed by the official critics “bourgeois,” and excessively concerned with “trivial female” preoccupations, instead of getting in line with revolutionary aims. As a result, after her book Anno Domini MCMXXI was published in 1922, she had great difficulty finding a publisher. A few years later, an unofficial ban on Akhmatova’s poetry began, which lasted from 1925 until 1940. During this time, which she later called “The Vegetarian Years,” Akhmatova devoted herself to literary criticism, particularly of Pushkin, and translation: she translated Italian, French, Armenian, and Korean poetry. The impact of the nationwide repression and purges had a decimating effect on her St Petersburg circle of friends, artists and intellectuals: many left the country, others were imprisoned, executed or committed suicide. Akhmatova narrowly escaped arrest, though her son, historian-anthropologist Lev Gumilyov was imprisoned on numerous occasions by the Stalinist regime, accused of counter-revolutionary activity, and for simply being his father’s son. During the long period of imposed silence, Akhmatova did not write much original verse, but the little that she did compose—in secrecy, under constant threat of search and arrest—is a monument to the victims of Stalin’s terror. Between 1935 and 1940 she composed her long narrative poem Реквием [Requiem], which was published for the first time in Russia during the years of perestroika. It was whispered line by line to her closest friends, who quickly committed to memory what they had heard. She was frequently confronted with official government opposition to her work even after World War II; her poems were once again banned and she was expelled from the Writer’s Union, to which she had been admitted a few years before. Akhmatova achieved full recognition in her native Russia only after her death in 1966, in the late 1980s, when all of her previously unpublishable works finally became accessible to the general public.

Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin, The Portrait of Anna Akhmatova, 1922

oil on canvas, exhibition print

State Russian Museum St. Petersburg, Russia

The rapid industrialization during the First Five-Year Year Plan crystalized the regime’s ideas about the “new soviet man”: a productive member of society, working in a factory, ready to offer his or her free time and creative capacities to the great cause of the building of Socialist society. One of the projects that were directed to capture the Socialist imagination was the city of Magnitogorsk [Магнитого́рск, “(city) of the magnetic mountain”], in the Chelyabinsk Oblast, east of the Ural Mountains, which was named after the nearby mountain Mount Magnitnaya, a geological formation consisting largely of iron ore. Although there had been a minor iron works in the city since the 18th century, the Magnitogorsk Iron and Steel Works (MMK) was a product of the First-Five Year Plan. Magnitogorsk was not only modeled after such advanced North-American steel-producing cities as Pittsburg; it was with the help of American experts, (the Arthur and MacKee Company), that the groundwork of this magnificent city and its main production company was laid out. The American contractors were not used to the forced tempo of the Five-Year-Plan: there were disagreements regarding the timetable and massive shortages of supplies, changes in leadership (due to political reasons). Yet, thousands of idealistic Soviet workers streamed in, the furnaces at MMK were put in action in 1932, and steel production began in 1933 (after a necessary and quite long technical break). But the “new soviet man” was not born from one day to the other: a large proportion of the workforce, as ex-peasants, had few industrial skills and little industrial experience. To solve these issues, several hundred foreign specialists arrived to direct the work, including a team of architects headed by the German Ernst May. He made the ground plans for the surrounding city, which he constantly had to redesign because the city was simultaneously being built and lived in. By the mid-1930-s, the MMK was almost fully operational, yet, due to the rising terror, the city’s openness evaporated along with the illusions of its inhabitants. In 1937 foreigners were told to leave, and Magnitogorsk was declared a closed city; it played a major role during WWII in the Soviet victory over Nazi Germany.

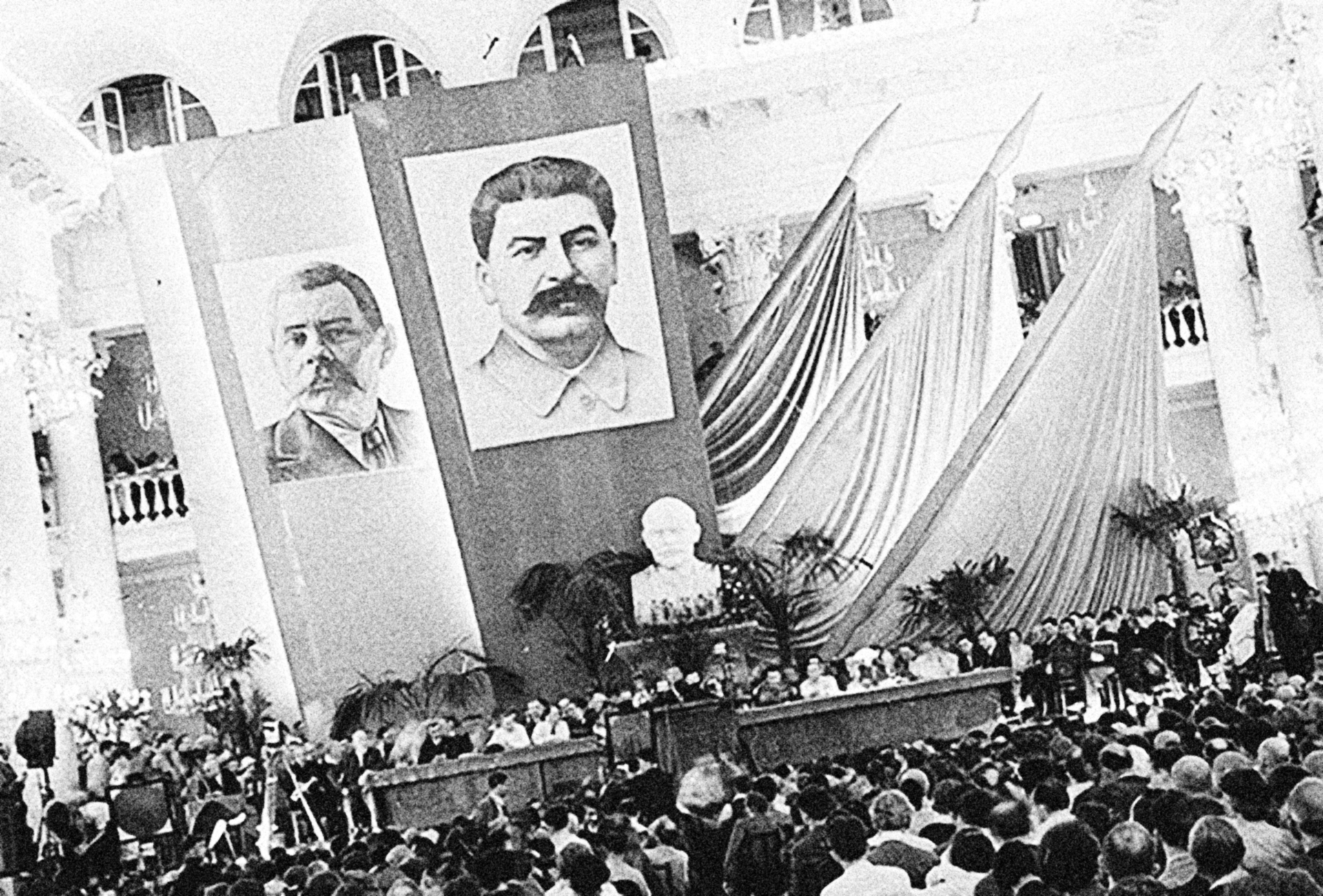

Ceremonial meeting at Magnitogorsk, at the Kabakov ore mine, 1930s

bw. photo, exhibition print

Sputnik / Alamy

Architecture and urban planning were assigned a special role in underpinning state power. The Soviet Union not only wanted to create a new type of human being, but also wanted to revolutionize the appearance of Russian cities according to socialist ideas. Moscow’s old city center was drastically transformed in a couple of years, according to a “General Plan”. The General Plan presented Moscow as an ideal garden city, surrounded by a broad belt of forests and parks, and with large spaces to celebrate May Day and The October Revolution. The crowning glory of the “New Moscow” was to be the Дворец Советов [Palace of the Soviets]: at 415 meters the tallest building in the world with a 100 meter-high statue of Lenin on top. The Palace was planned to house the administrative center and a congress hall. Construction started in 1937, on the site of the demolished 19th-century cathedral Храм Христа́ Спаси́теля [Cathedral of Christ the Savior]. A second major edifice, the building of the People’s Commissariat of Heavy Industry was also planned to complement the ensemble in the vicinity of the Red Square. The structure of the “General Plan” thus corresponded to the structure of the utopian model of society that was being built by Stalin. Architects Boris Iofan, Vladimir Shchuko and Vladimir Gelfreikh won the lengthy series of architectural contests—and the approval of Stalin himself—with their plan using resources of classicism combined with an arsenal of Art Deco elements, thus launching a “retrospectivist” movement in Soviet architecture. With the beginning of World War II, however, the construction work was halted, and never resumed. In 1958, the foundations of the Palace were converted into what would become the world’s largest open-air swimming pool, the Moscow Pool. The cathedral was rebuilt in 1995–2000.

Boris Iofan, Vladimir Shchuko, Vladimir Gelfreikh, Design plan for the Дворец Советов [Palace of the Soviets], 1931–1933 (1946)

pencil, watercolor and white pigment on paper, exhibition print

Shchusev Architecture Museum, Moscow

In the emergence of a new form of architecture in the 1930s, one particularly strong influence was that of the architecture of the Moscow Metro, which was created not only as a utilitarian means of transport but as an architectural ensemble of palatial stations. The Metro was officially linked to the evolution of a new Soviet architecture: “Our Metropolitan Railway is a prototype of the general Socialist organization of public services, and this is its great historical significance. The construction of the Metro inaugurates a new and higher phase of Soviet architecture, which will be manifested in the reconstruction of Moscow.” In January 1932 the plan for the first lines was approved, and on 21 March 1933 the Soviet government approved a plan for 10 lines with a total route length of 80 km (50 mi). The first, 11-kilometer section of the Metro connected Sokolniki to Okhotny Ryad then branched towards Park Kultury and Smolenskaya; it was opened to the public in May 1935. The day was celebrated as a technological and ideological victory for Socialism (and, by extension, Stalinism). The engineering and the design of the stations varied with structural factors and the depth of the site. Among the most spectacular stations are Kropotkinskaya (designed by Alexey Dushkin and Yakov Lichtenberg, 1935) and Krasnye Vorota—The Red Gate (designed by Ivan Formin, 1934–1935).

Alexey Dushkin, Yakov Lichtenberg, Design for the Kropotkinskaya [Кропоткинская] Metro Station, 1935

pencil, watercolor and white pigment on paper, exhibition print

Shchusev Architecture Museum, Moscow

One might say that Aleksandr Samokhvalov [Алекса́ндр Николаевич Самохвалов] followed the archetypical career of the ideal Soviet painter. He did not study abroad: from 1914 he was a student of Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin [Кузьма Сергеевич Петров-Водкин] at the Higher Art School of the Imperial Academy of Arts in Saint Petersburg, but because of the revolution and the Civil War he could only graduate in 1923—at the time the school had already been renamed as Vkhutemas [Вхутемас, acronym for Высшие художественно-технические мастерские; Higher Art and Technical Studio]. Unlike his fellow Leningrad artists who were closer to the avant-garde, he did not really participate in the “Cultural Revolution”. He gradually became interested in the older masters of Russian painting and the cultural heritage of the Soviet Union. This later turned out to be a useful choice, since Stalin himself had come to favor figurative art with a romantic air above all else, being especially keen on the 19th-century group of painters, the Peredvizhniki [Передвижники, the “Wanderers” or “Itinerants”]: Ilya Repin, Vasily Perov, and others. Samokhvalov always belonged to the most appropriate artistic organizations, and after 1932, when all artistic associations were dissolved, Samokhvalov became a member of the Leningrad branch of the one and only Union of Soviet Artists, where he was deputy chairman from 1938 to 1940. Samokhvalov was commissioned to create many genre and historical paintings; among them was Sergei Kirov Reviews an Athletic Parade, one of the many monumental works depicting Sergei Kirov after his tragic death in 1934. Kirov, who was the main rival of Stalin as the head of the Party in Leningrad and a member of the Politburo, was allegedly murdered by a group of anti-Bolshevist conspirators, led by Trotsky (though Kirov’s death was most probably orchestrated by the NKVD, on the order of Stalin himself). The campaign around the “fallen hero” gave momentum to Stalin to embark on what we now call “The Great Purge,” to which many artists fell victim, but from which the ideal Soviet painter emerged unharmed.

Aleksandr Samokhvalov, С. М. Киров принимает парад физкультурников [Sergei Kirov Reviews an Athletic Parade Parade], 1935

oil on canvas, exhibition print

State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

Another “ideal” Soviet painter was Aleksandr Deineka [Александр Александрович Дейнека]. The artist’s youth, like many of his contemporaries, was associated with revolutionary events. During the turbulent years after the revolution he designed agitprop trains, theatrical performances, and participated in the defense of Kursk agains the Whites. It was the army who sent him to study in Moscow, at the VKHUTEMAS’ printing department. The years of apprenticeship and meetings with Mayakovsky became of great importance in the creative development of the artist. In the early 1930s, Deineka began to paint canvases that were more legible and naturalistic than his overtly modernist, montage-like and industrial compositions of the 1920s. This shift in his work—and in the work of other Soviet artists of this time—is usually interpreted by historians of modern art as a sign of capitulation to the demands of the new style of Socialist Realism. As one later critic of Socialist Realism put it, Deineka was not damaged by official criticism of artistic “formalism” in the 1930s because he had already “bent sufficiently in the prevailing wind.” Other art critics, however, point out his immense success in the West—having a solo exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1935, designing a cover for Vanity Fair, etc.—and suggest that this shift in his work might have had far more to do with his integral artistic development than the suffocating regulations and doctrines of Soviet cultural life. As one of them writes: “Leninist freedom and official patronage of Socialist Realism did not lead only to bad work, or to forced artistic labor. When we hear Deineka speak of the Soviet artist’s freedom to travel around the country painting modern, relevant themes, when he says: ‘In this sense we are pioneers and in this sense people will learn from us,’ we should consider the possibility not only that he meant what he said, but that he might have been right. To understand the work of Deineka and others such as him in the 1930s only as forced labor is to strip the artists of their subjective will—to deprive them of their subjectivity through art history, just as we accuse Stalinism of having done in history.”

Aleksandr Deineka, Бегуны [Runners], 1934

oil on canvas, exhibition print

State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

Unlike Samokhvalov or Deineka, Kazimir Malevich [Казимир Северинович Малевич] soon became the target of harsh criticism, long before the official anti-formalist campaign was launched in 1936. In the immediate aftermath of the revolution, vanguard movements such as Malevich’s Suprematism and Vladimir Tatlin’s Constructivism were encouraged by Trotskyite factions in the government. Malevich—like Majakovsky or El Lissitzky—did not shy away from propaganda work, creating, for instance, content and propaganda materials for the so-called agitprop trains. In the early Soviet period, Malevich was a well-established artist, holding different posts and teaching positions in major Soviet cities. In 1923 he was appointed director of GInKhuK [ГИНХУК, Государственный институт художественной культуры, State Institute of Artistic Culture] in Petrograd, and it was here that the first attacks against the avant-garde began. In June 1926, an article was published in the city’s party newspaper, with the title “A Monastery on a State Subsidy,” which accused the institution of being rife with “counterrevolutionary sermonizing and artistic debauchery.” The GInKhuK was subsequently closed down. In 1927, Malevich traveled to Warsaw and Germany (Belin and Munich), where he held his first major exhibition outside Russia. The travels finally brought him international recognition, but they also led to serious accusations a few years later. In autumn 1930, he was arrested and interrogated by the NKVD in Leningrad (Petrograd was named after Lenin from 1924), accused of Polish and German espionage, and threatened with execution. He was released from imprisonment in early December. Like many of his fellow avant-garde artists, he became increasingly isolated. Malevich began a series of pastiches of his earlier paintings from 1911–12 of peasants working in the fields, but their context and meaning was now transformed. At a time when agriculture was being savagely collectivized under the First Five-Year Plan, Malevich elevated the redemptive image of the suffering peasant into a kind of Passion that seemed to symbolize the fate of Russia. He also made portraits—even very conventional ones—during his last years, where he seemed to return to his early impressionist period. But in spite of his encounter with the NKVD, and after being expelled from various functions, he could still exhibit his work—unlike many of his colleagues. He died in 1935. After his death the Leningrad city council organized a public funeral, and many of his paintings were purchased by the Russian Museum. Although he and his circle had been severely criticized, and some of them were arrested, it was still recognized that Malevich had made a substantial contribution to Soviet culture. But his funeral signaled the death of the avant-garde.

Kazimir Malevich, Портрет мужчины [Portrait of a man], 1933–1934

oil on canvas, exhibition print

State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

Stalin’s and Lenin’s images, names, and words—along with other anointed persons and themes—were everywhere to be seen in the Soviet Union, including usable or displayed household objects, industrial goods, films, plays, recordings, and restaurant menus. This led many contemporaries to conclude that in the exploitation of the new media and mass culture, the balance between dictatorship and democracy tilted toward the former. Stalin became a popular subject for some avant-garde artists, too. Pavel Filonov’s [Павел Николаевич Филонов] portrait of Stalin was made after he was harshly criticized and persecuted by the regime. In 1929, his retrospective exhibition was planned at the Russian Museum; the paintings were hung, the catalogue written, but it was never opened to the public. The paintings remained on the walls of the museum for two years, and were accessible for a few chosen visitors, and their reactions became a mirror image of the broader polemic in the press. Filonov became a test case and the closed exhibition a battle ground between conflicting tendencies. The often repeated charge of “Filonovism” stated that his works are “devoid of living ties with the working class.” Filonov was defeated, yet he continued to work. Though his work was no longer favored and his friends and family were arrested, Filonov’s faith in the cause did not falter. The apocalyptic and hermetic imagery of his paintings in the late 1930s clearly reveals that for him it was the Party which had lost its way, not the artist. With many others, Filonov starved to death in the wartime siege of Leningrad.

Pavel Filonov, Portrait of Stalin, 1936

oil on canvas, exhibition print

State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

Soviet mass culture—a mixture of heavy-handed direction and indulging popular tastes—does not necessarily need to be set against the culture of avant-garde modernism. On the contrary: prominent members of the Soviet photographic and filmic avant-garde eagerly embraced mass media mixing so-called high with low. Photographers (and filmmakers) in the Soviet Union, at a time when the manipulation of images began to acquire far greater sophistication and application across many countries, explored montage and other techniques in a mass culture with political purpose. Among them was Latvian photographer and constructivist artist Gustav Klutsis [Gustavs Klucis, Густав Густавович Клуци], who, while graduating from and later teaching at VKhUTEMAS, became an active member and loud advocate of the Party. In 1931, Klutsis wrote Photomontage as a New Problem in Agitation Art, published in Art-Front: Class Struggle on the Visual Arts Front [Изофронт. Классовая борьба на фронте пространственных искусств] by the October Group [Группа «Октябрь»], whose members included Klutsis, Alexander Rodchenko, El Lissitzky and Sergei Eisenstein. He wrote, “The old kinds of visual art (drawing, painting, engraving), with backward technique and methods of work, turned out to be inadequate to the mass agitation of the Revolution”. Instead, Klutsis proposed photomontage as the new art form for Socialist culture: “Proletarian industrial culture, which has advanced the most expressive methods of affecting the masses, uses the method of photomontage as the most aggressive and expressive means of struggle.” Together with his wife and collaborator, Valentina Kulagina [Валентина Никифоровна Кулагина-Клуцис], Klutsis created many propaganda materials using photomontage: promoting the First Five-Year Plan, or the underground railway constructions in Moscow, gradually adopting Socialist Realism in their work. By the mid-1930-s, the once-celebrated medium of photomontage was criticized for being too inaccessible, monotonous and ambiguous. Despite his active and loyal service to the Party, Klutsis was arrested in Moscow in 1938, accused of participating in a Latvian fascist group. He was executed some months later. Kulagina was never told the truth about what happened to her husband, believing for the remainder of her life that he had died of a heart attack while imprisoned. In 1989, two years after her death in Moscow, it was discovered that Klutsis had been executed by order of Stalin, very soon after his arrest. He was rehabilitated only after Stalin’s death, in 1956 for lack of corpus delicti.

Gustav Klutsis, Культурно жить – производительно работать [Civilized Life — Productive Work], 1932

poster, exhibition print

Russian State Library, Moscow

The attack on Malevich in 1926 proved to be the beginning of the denunciation of what came to be regarded as the “formalist” art of the suprematist, constructivist, and productivist movements. In 1928, an article in Sovetskoye Foto attacked Aleksander Rodchenko [Александр Михайлович Родченко], accusing his photographic work of plagiarizing the “formalist” aesthetics of foreign non-Soviet photographers (like László Moholy-Nagy), initiating a debate that over the following years would develop, in an increasingly eerie way, into the most narrow definition of the “correct” depiction of reality. Artists such as Lissitzky, Rodchenko, Tatlin, and Klutsis saw themselves forced to compromise, publicly apologize for their “formalist” tendencies, and to retreat from the public eye while taking on socialist realist commissions following the outlines of Stalin’s cultural policies. In some cases, this proved not sufficient to take away the suspicion of their revisionist tendencies. In January 1932, Rodchenko was expelled from the photo-reporting section of the October Group—which would soon be dissolved in accordance with the 1932 party resolution. As a photo-reporter he documented the building of the White Sea Canal, where convicts, at great loss of human life, were constructing a useless monument to stupidity. In his photo-works in the 1930s, he concentrated on sports photography and images of parades and other choreographed movements. With his partner Varvara Stepanova [Варва́ра Фёдоровна Степа́нова], he was able to find limited work as a designer of official photo albums commemorating major events and achievements of Socialist Society. They also created thematic issues of the СССР на стройке [USSR in Construction] magazine. Of course, it was pathetic editing, commissioned work on such topics as “The First Horse”, “10 Years of Uzbekistan”, “Red Army”. Rodchenko and Stepanova tried to turn this official theme into culturally meaningful publications, in which there were many original documentary photographs, the printing possibilities were interestingly played up—printing on silk, celluloid, silver paper, various types of cutting, complex folding. In 1935, in the privacy of his studio, Rodchenko began to paint again—an activity he had rejected fourteen years before, when he exhibited the three monochrome canvases that he then considered to be his final statement in the medium. His new subjects came from the world of the circus, which was not only a favorite subject matter for many artists before him. The carnivalesque culture was also an important feature of Stalinist culture during the mid-1930s.

Aleksander Rodchenko, Женская пирамида [The Female Pyramid], 1936

bw. photograph, exhibition print

The Rodchenko and Stepanova Archive, Moscow

Not everything in the Soviet mass repertoire revolved around industrialization and politics. Stalin’s infamous pronouncement in 1935 that “life has become better, life has become more joyful” was used as a guideline for the organization of free time and leisure. The meeting of mass culture and mass politics —so characteristic of dictatorships—could be found in fashion, school assignments, the naming of newborns, and circus routines. The most important venue for leisure activities was Gorky Park—officially: the Gorky Central Park of Culture and Leisure [Центральный парк культуры и отдыха (ЦПКиО) имени Горького]—, which became a “fairground for building the new man”. Established in 1928, the park was built to the plans of Konstantin Melnikov, a widely known Soviet avant-garde and constructivist architect, and amalgamated the extensive gardens of the old Golitsyn Hospital and the Neskuchny Palace. The park was named after Gorky in 1932, after his return to the Soviet Union. Through its constant remodeling (both physically and conceptually) during the 1930s, the Park demonstrated the development of Soviet policy towards environmental (and particularly urban) acculturation. The “joyful life” was celebrated during the first “Soviet carnival” that took the form, beginning in the July 1935 celebration of the Soviet constitution in Gorky Park, of a variety show with jugglers, costumed figures taken from fairy-tales, confetti, and dance bands. Orchestras played tangos, fox-trots, waltzes and jazz, as the propagandists trumpeted agitprop songs.

Poster for the third carnival at the Gorky Park, Moscow, 1937

poster, exhibition print

Archives of Gorky Park, Moscow

Students preparing for the carnival in Gorky Park, 1935

bw. photo, exhibition print

Archives of Gorky Park, Moscow

The ideological debates around “formalism“, in reality, were relevant only to a small circle of intellectuals and artists. The most important cultural battle of the early Soviet Union that concerned large masses was the struggle against illiteracy. The campaign “Ликбез” [“Likbez”, abbreviation for ликвидация безграмотности, meaning “elimination of illiteracy”] aimed at eradicating illiteracy in Soviet Russia and the Soviet Union in the 1920s and 1930s. When the Bolshevik Party came to power in 1917, they inherited—among many other things—a poor education system from Tsarist Russia: in 1917, only circa 37.9% of the male population (above seven years old) was literate, and only 12.5% of the female population could write and/or read. “Without literacy,” Lenin declared, “There can be no politics, there can only be rumors, gossip and prejudice.” According to the decree “On the eradication of illiteracy among the population of RSFSR” signed in December 1919, all people from 8 to 50 years old were required to become literate in their native language. 40,000 liquidation points (ликпункты) were arranged to serve as centers for education, and achieving literacy. The campaign started in 1920, but faced many difficulties during the Civil War, and constant budget cuts. It became increasingly hard to find teachers who were willing to live in far-off regions of the Soviet Union, where illiteracy was the highest. In many cases, peasant and proletariat students met their educators and literacy teachers with hostility due to their “petty bourgeois” backgrounds. By the 1930s, as Stalin consolidated his power, the push for pro-literacy propaganda had lost some of the fervor that it had in the previous decade. Indeed, throughout the 1930s, propaganda became increasingly focused on glorifying the Soviet State and its leader, instead of on the emancipation of the masses.

Teaching the population to read and write in the village of Shorkasy (Cheboksary district, Chuvashia), 1930s

bw. photo, exhibition print

kulturologia.ru

Daily newspaper circulation rose from 9.4 million in 1927 to 38.4 million by 1940. Soviet newspapers printed an amalgam of hard news framed by party directives, agitprop, educational materials, and unapologetic amusements. In the early 1920s, around 90 percent of journals published in Soviet Russia were subscribed to in Moscow and Petrograd. Of the several hundred thousand copies of Pravda and other central newspapers printed daily, only a few thousand went beyond the two capitals and the three or four biggest regional centers. This, too, gradually changed during the 1930s, and newspapers were also increasingly read in the provinces.

Collective reading of a rural newspaper, Kharkiv region (Ukraine), 1932

bw. photo, exhibition print

kulturologia.ru

In the Soviet Union, the number of cinemas rose very quickly in the 1930s: from 7,331 in 1928 to nearly 30,000 by 1940, according to official statistics; especially in the countryside, where “cinema installations”—projection booths, outdoor projection installations—served as the main venues of culture and propaganda. With increasing centralization in the 1930s, the film industry gradually lost its former creative independence and energy. Soviet film studios produced Hollywood-style musicals and Civil War pictures, with political newsreels invariably shown prior to all films. Many educational films were also produced and circulated. Foreign films were shown in the Soviet Union in the 1930s, but their number decreased for both budgetary (hard currency) and ideological reasons. Soviet filmmakers also had to adopt the doctrine of Socialist Realism from 1932 on. From 1933 GUKF [Государственное Управление Кинемотографии и фотографии, The Chief Directorate of the Film and Photo Industry] replaced the former film organizations. It was headed by Boris Shumyatsky [Борис Захарович Шумяцкий], who was in charge of all matters of production, import/export, distribution and exhibition. Under his rule, the Soviet sound film was born, but it was not only technical innovations that he introduced to the film industry. Tired of aesthetically ambitious films that confused the average Soviet viewer, Shumyatsky demanded films that were “accessible,” enjoyable and entertaining. He dethroned the avant-garde kings of the cinema, foremost among them Sergei Eisenstein [Сергей Михайлович Эйзенштейн]. While Eisenstein and others found themselves stymied by the bureaucracy, other directors who could satisfy popular tastes found that the new system encouraged their work. Among the most outstanding films of the mid-1930-s was Chapaev [Чапаев], directed by the Vasilyev brothers [Васильев]: a film about Russian revolutionaries and society during the Revolution and Civil War.

Poster of the film Чапаев [Chapaev], 1934

poster, exhibition print

ruskino.ru

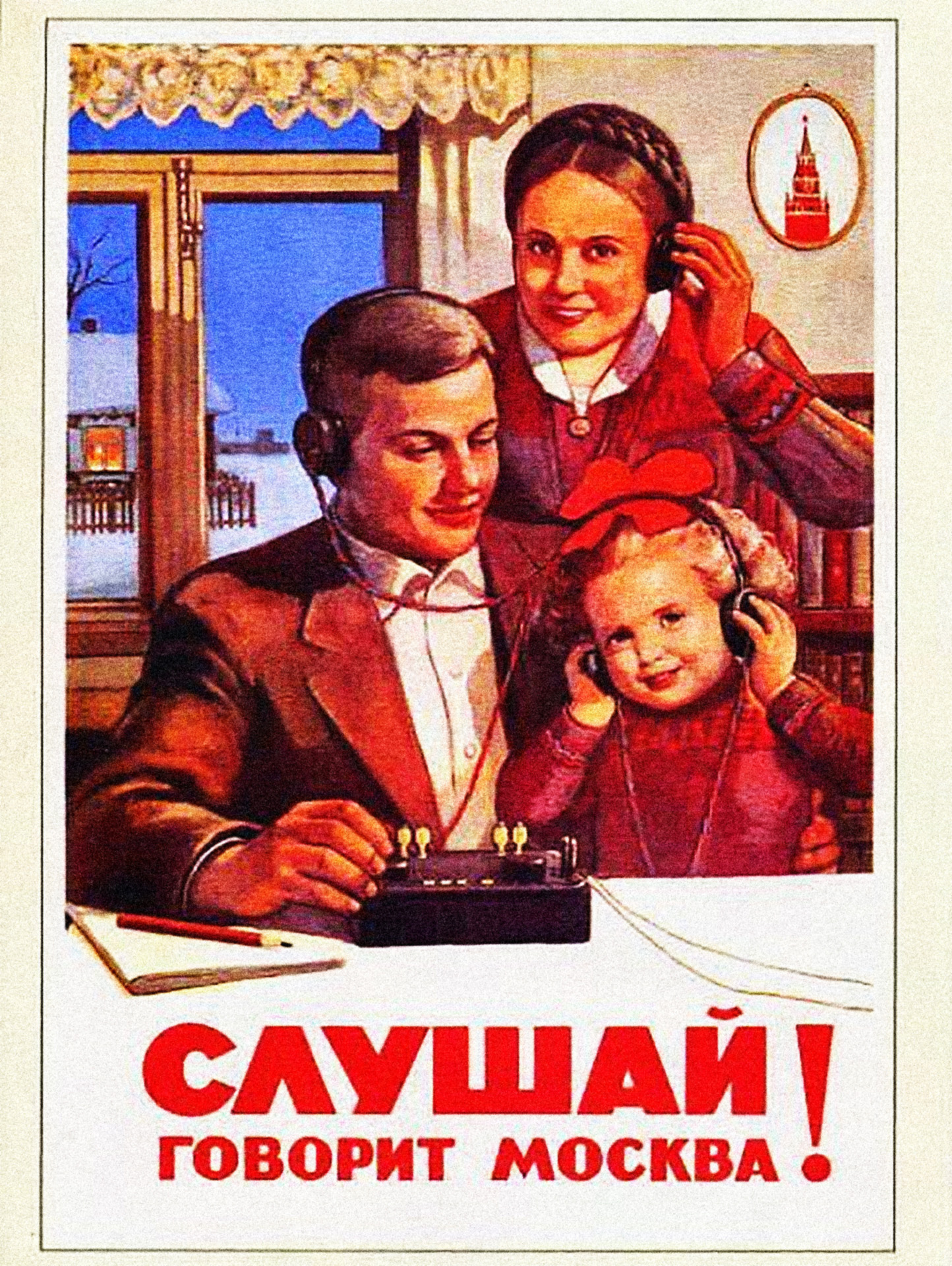

One of the first means of education and political agitation in the Soviet Union in the 1920s and 1930s was the developing radio broadcasting system; regular radio broadcasting in the USSR began in 1924. Ideological control over the material that was broadcast was exercised by the People’s Commissariat for Education. At first, traditional censorship had a hard time adjusting to the new format because of technical limitations, and at the beginning radio offered the opportunity for public discussion and exchange of views. This soon changed: instead of a means of transmitting information, in many ways, radio became an instrument for concealing it.

“Слушай! Говорит Москва” [Listen! Moscow speaking], 1935

poster, exhibition print

kulturologia.ru

In the 1930s, the majority of radios were still simple cables or wires, not wave receivers, and they could only tune in to the official stations. The airwaves carried industrial marches and melancholy crooners, amidst state propaganda and news. The 1932 Second Five-Year Plan envisioned the production of 14 million wave radio receivers, but in 1937 only 3.5 million were in operation. Soviet industry could not manufacture sufficient quantities of vacuum tubes. Cable or wire remained the dominant form of Soviet radio for a long time, still accounting for two out of three radios into the 1950s.

Collective listening to radio broadcast, 1930s

bw. photo, exhibition print

kulturologia.ru