For a long time, the terms Fascism and Modern Art used to seem comfortingly opposed to each other. How could a political force that represented “imperfect totalitarianism,” or “a terroristic form of capitalism” be considered capable of any significant cultural production, let alone a future-oriented, modernist one? The last two decades of scholarship in history, art history, and literature have radically revised this postwar assumption. In fact, Italian Fascism was particularly full of contradictions and ambiguities. At times the cultural climate allowed dissent; unlike Nazi Germany and the 1930s Soviet Union, it even encouraged experimentation and sustained a degree of coexistence of differing attitudes. Once Fascism came to power, there emerged the question of an official state art. But despite its much-vaunted aesthetic proclivities, Fascism did not move in this direction, seemingly preferring the broader legitimation that might be gained through a policy that one historian has dubbed “aesthetic pluralism”. In 1923, Mussolini famously claimed that “I declare that it is far from my idea to encourage anything like a state art. Art belongs to the domain of the individual. The state has only one duty: not to undermine art, to provide humane conditions for artists, to encourage them from the artistic and national point of view”. Following this, the “exceptional laws” [Leggi Eccezionali] of 1926 only referred to members of the (former) Opposition, the so-called “Aventinian” deputies, like Marxist philosopher and politician Antonio Gramsci. Italian intellectuals and artists were “only” harassed and persecuted on the grounds of their political views, not of the art form or style they chose to work in.

During the 1930s, and, to a lesser extent, even after the introduction of the Racial Laws [Leggi Razziali] in 1938, Fascist Italy continued to have a pluralistic approach towards culture, largely defined by the former futurist and “enlightened” Fascist, Giuseppe Bottai, who in various capacities was the most important figure in Italian culture in the 1930s. An intelligent and cultivated man, Bottai expressed his views on culture early on. In 1927 his review Critica Fascista launched a debate on the notion of a possible fascist art, and Bottai summarized the results: with an emphasis on italianitá or “Italianness”, a Fascist art should represent the continuation of the grand Italian tradition; it should not simply imitate the styles of the past but should infuse Italy’s abiding characteristics of order, solidity, and clarity with a modern sensibility. The state should not attempt to influence individual creativity by imposing formulaic or stylistic preferences. Instead it should provide a framework that would secure the livelihood of artists while supervising the quality of production. Although Bottai’s directives afforded artists a certain creative freedom, the state’s gradual establishment of rigid formal structures ensured a covert and insidious form of control. As part of the Fascist corporative system of “syndicates”, the Federazione dei Sindicati Intelletuali (changed to Confederazione dei Professionisti e degli Artisti in 1931) incorporated organizations for writers, musicians, painters, etc. In order to work or participate in any art project organized by the regime, an artist had to register with the syndicate and be in possession of a Fascist party membership card. The level of control depended on the individuals in authority. It appears that many artists passively colluded with the regime so as to be allowed to continue their work, but many of the most gifted Italian painters, sculptors, and architects believed wholeheartedly in a Fascist culture and worked devotedly to realize it.

By 1932, when his doctrine “Dottrina del Fascismo” [The Doctrine of Fascism] was published in the Enciclopedia Italiana, Mussolini was drawing on ancient Rome as a model for his nationalistic and imperialistic aims, and the concept of romanità, the cult of ancient Rome became dominant. With himself a “condottiero-like” figure, at Italy’s helm, he envisaged a Fascist nation asserting its power and dominating the Mediterranean world. The image of the Duce as the “savior of Italy”, was primarily imposed through the propaganda machine of the Ufficio Stampa (later the Ministry of Press and Propaganda). Apart from the obvious allure of his oratory, endless photographs, films, busts, paintings, and equestrian monuments of the Duce were used to seduce the Italian people. The cult around the Duce was largely based upon theatrical forms from the very beginning. In this, Mussolini was greatly helped by the man who would become, in effect, his minister of propaganda and chief image-counselor, Giovanni Starace, appointed in December 1931. Starace conceived and organized the “oceanic” demonstrations of tens of thousands of Romans in Piazza Venezia, beneath the Duce’s speaking balcony with its hidden podium; he abolished the “insanitary” handshake in favor of the “hygenic” Roman-based Fascist salute. And he made sure that the orchestrated cheers of the crowd were directed only to Mussolini: “One man and one man alone must be allowed to dominate the news every day, and others must take pride in serving him in silence.”

The theatralization of Italian public life was followed with awe—and disgust—in many countries of Europe. In Hungary, while the Gömbös-government was busy forging close links with the Fascist dictatorship, Leftist intellectuals—like Attila József—followed the mass spectacles with growing fear. Yet, it is highly misleading to think of the Fascist movement as a product of “mass society.” On the contrary, a true mass society started to emerge only in the mid-1930s, with the growing importance of the media. Even then, Italian society remained fragmented, with vast areas of isolation and backwardness in which the messages of mass culture could be received only very faintly, if at all. The totalitarian aspiration to create a mass public, which Fascism shared, found its practical limitations in these difficulties of communication.

Mario Sironi, Condottiero a cavallo [Leader on Horseback], 1934–35

mixed media on “spolvero” paper, exhibition print

Mart, Museo di arte moderna e contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto

Alessandro Blasetti and Giuseppe Bottai, 1935

bw. photo, exhibition print

Scenario, n.1, January 1935

Poster of the mass spectacle 18BL (design by Ferdinando Gatteschi), 1934

poster, exhibition print

“18 BL: Spettacolo di masse per il popolo,” Gioventù fascista 4, no. 8 (15 April 1934): 13. / Blasetti Archive

Catalog of the exhibition Mostra della Rivoluzione Fascista [Exhibition of the Fascist Revolution], Rome, 1932

exhibition print

Archivio Centrale dello Stato, Rome

Musssolini’s reign, and his wish to become “Il Duce” was largely influenced by one of the most celebrated Italian literary figures of the turn of the century, Gabriele D’Annunzio. During the First World War, D’Annunzio, often referred to under the epithets Il Vate [the Poet] or Il Profeta [the Prophet], became a national war hero, taking part in actions such as the Flight over Vienna. As part of an Italian nationalist reaction against the Paris Peace Conference, he set up the short-lived Italian Regency of Carnaro in Rijeka (Fiume) [Reggenza Italiana del Carnaro] with himself as “Duce” or “Comandante”. The constitution made “music” the fundamental principle of the state and was corporatist in nature. After the Carnaro episode, D’Annunzio retired to his home on Lake Garda and spent his last years writing and campaigning. Although D’Annunzio had a strong influence on the ideology of Benito Mussolini, he never became directly involved in Fascist government politics in Italy.

Gabriele D’Annunzio, around 1922

bw. photo, exhibition print

Agence de presse Meurisse / Bibliothèque nationale de France

Modern Italian art—especially futurism—and Fascism were, indeed, in many ways connected through their belief in technical acceleration and their fixation on war. Yet, futurism never became the official art of Fascist Italy. After gaining international recognition with his avant-garde poems before WWI, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti founded the Partito Politico Futurista [Futurist Political Party] in early 1918, which only a year later merged with Benito Mussolini’s Fascist Party. After walking out of the 1920 Fascist Party congress in disgust, Marinetti withdrew from politics for three years, settling for a purely “aesthetic” definition of futurism’s public role. However, he remained a notable force in developing the party’s philosophy throughout the regime’s existence. Futurism, by this time, was fragmented. With a closer circle of futurists, Marinetti made numerous attempts to ingratiate himself and the futurist movement with the regime. But, despite Marinetti’s longstanding connection with Mussolini, which dated from the pre-war years, the regime never endorsed the futurist movement. No doubt it was attracted by the futurist insistence on technology and military aggression, but by the 1930s Fascism was more concerned with consolidating its image of discipline and order. Marinetti reiterated the fundamental italianità of futurism and strove to dissociate it from foreign movements, but the regime could never let itself be officially identified with any group that had it its roots in anarchism, in internationalism or the modernist avant-garde. Marinetti indeed continued to fight against tradition: he attacked, for instance, traditional Italian food. His 1930 Manifesto della cucina futurista [Manifesto of Futurist Cooking], in turn, would become a matter of artistic expression; many of the meals Marinetti described and ate resemble performance art. As the regime gradually turned against the avant-garde, he also became less radical: he accepted election to the Italian Academy, despite his condemnation of academies, saying, “It is important that futurism be represented in the Academy.” Similar controversies characterized his relationship with the church. Although he was an atheist, by the mid-1930s he had come to accept the influence of the Catholic Church on Italian society. He even took a hand in promoting religious art, and declared that Jesus Christ had been a futurist. Nevertheless, he remained true to his youthful war-mongering dreams, and volunteered for active service in the Second Italo-Abyssinian War and the Second World War, serving on the Eastern Front for a few weeks in the summer and autumn of 1942 at the age of 65. He died of a heart attack in Bellagio in December 1944 while working on a collection of poems praising the wartime achievements of the Italian Decima MAS flotilla.

Filippo Tommaso Marinetti’s Futurist Food Preparation at Home, 1934

In the background: Umberto Boccioni’s Dinamismo di un calciatore [Dynamism of a Soccer Player, 1913]

colored photo, exhibition print

photo by W. Seldow/ullstein bild

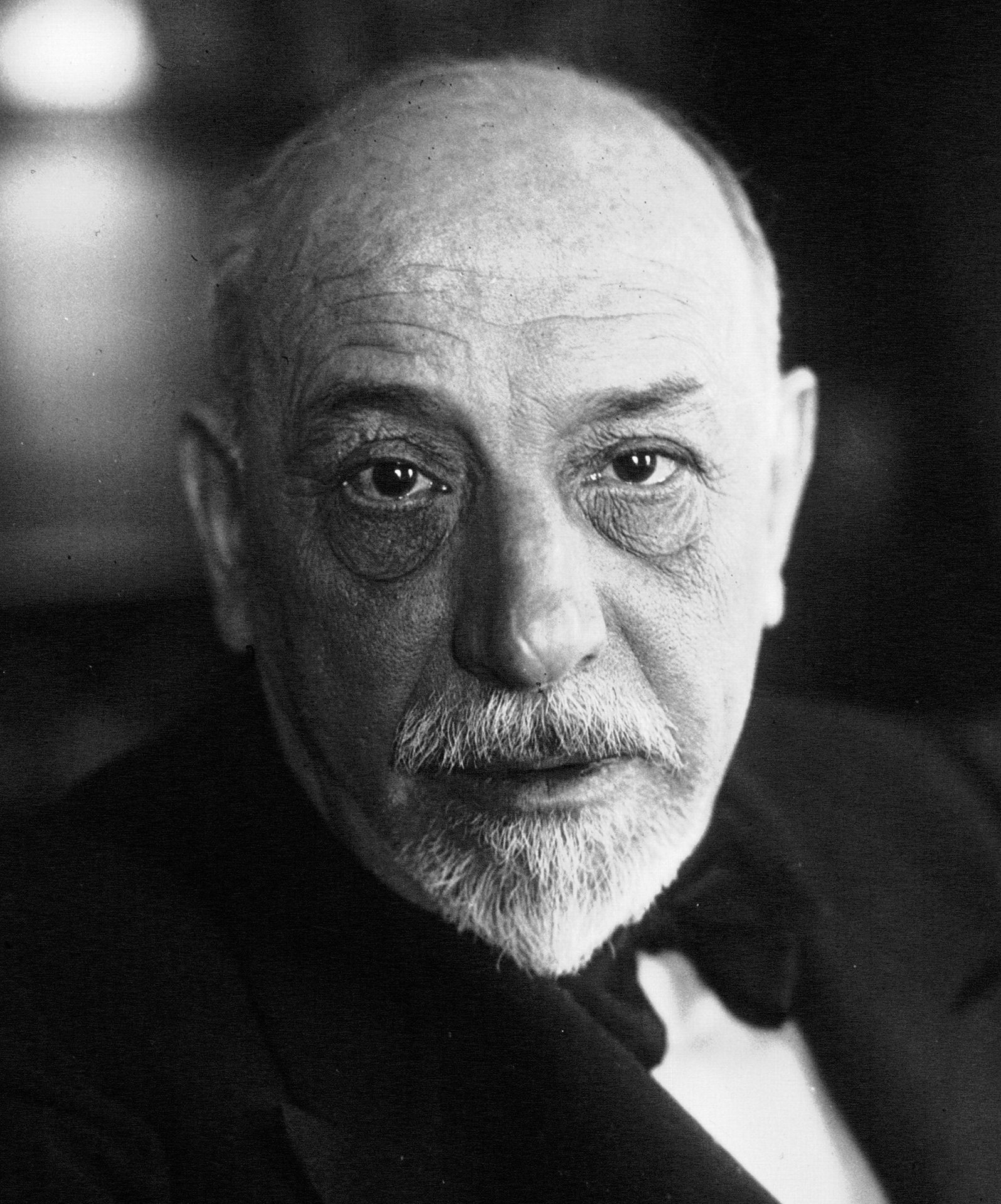

The theatralization of political and public life during Fascism also led to a (new) appreciation of theater in Italian culture. Drama, which a few playwrights and producers were trying to extricate from old-fashioned realistic formulas and the more recent superhuman theories of D’Annunzio, was increasingly dominated by Luigi Pirandello. To multiply the fragmentation of levels of reality, Pirandello tried to destroy conventional dramatic structures and to adopt new ones: a play within a play in Sei personaggi in cerca d’autore [Six Characters in Search of an Author, 1921] and a scripted improvisation in Questa sera si recita a soggetto [Tonight We Improvise, 1930]. Pirandello had a controversial relationship with the Fascist regime: In 1924 he wrote a letter to Mussolini asking to be accepted as a member of the National Fascist Party. In 1925, with the help of Mussolini, he assumed the artistic direction and ownership of the Teatro d’Arte di Roma. He described himself as “a Fascist because I am Italian.” Yet, he publicly expressed apolitical beliefs, and had continuous conflicts with famous Fascist leaders. In 1927 he tore his Fascist membership card to pieces in front of the startled secretary-general of the Fascist Party. For the remainder of his life, Pirandello was under surveillance by the Fascist secret police OVRA [Organizzazione per la Vigilanza e la Repressione dell’Antifascismo, Organization for Vigilance and Repression of Anti-Fascism]. Yet, during this time, he was nominated Academic of Italy in 1929. His unfinished play, I Giganti della Montagna [The Giants of the Mountain], written around 1933, has been interpreted as evidence of his realization that the Fascists were hostile to culture; yet, during a later appearance in New York, Pirandello distributed a statement announcing his support of Italy’s annexation of Abyssinia. Pirandello repeated and reinforced this statement, when he was awarded the 1934 Nobel Prize for Literature: he gave his Nobel Prize medal to the Fascist government to be melted down for the Abyssinia Campaign.

Luigi Pirandello, 1932

bw. photo, exhibition print

Agence de presse Meurisse / Bibliothèque nationale de France

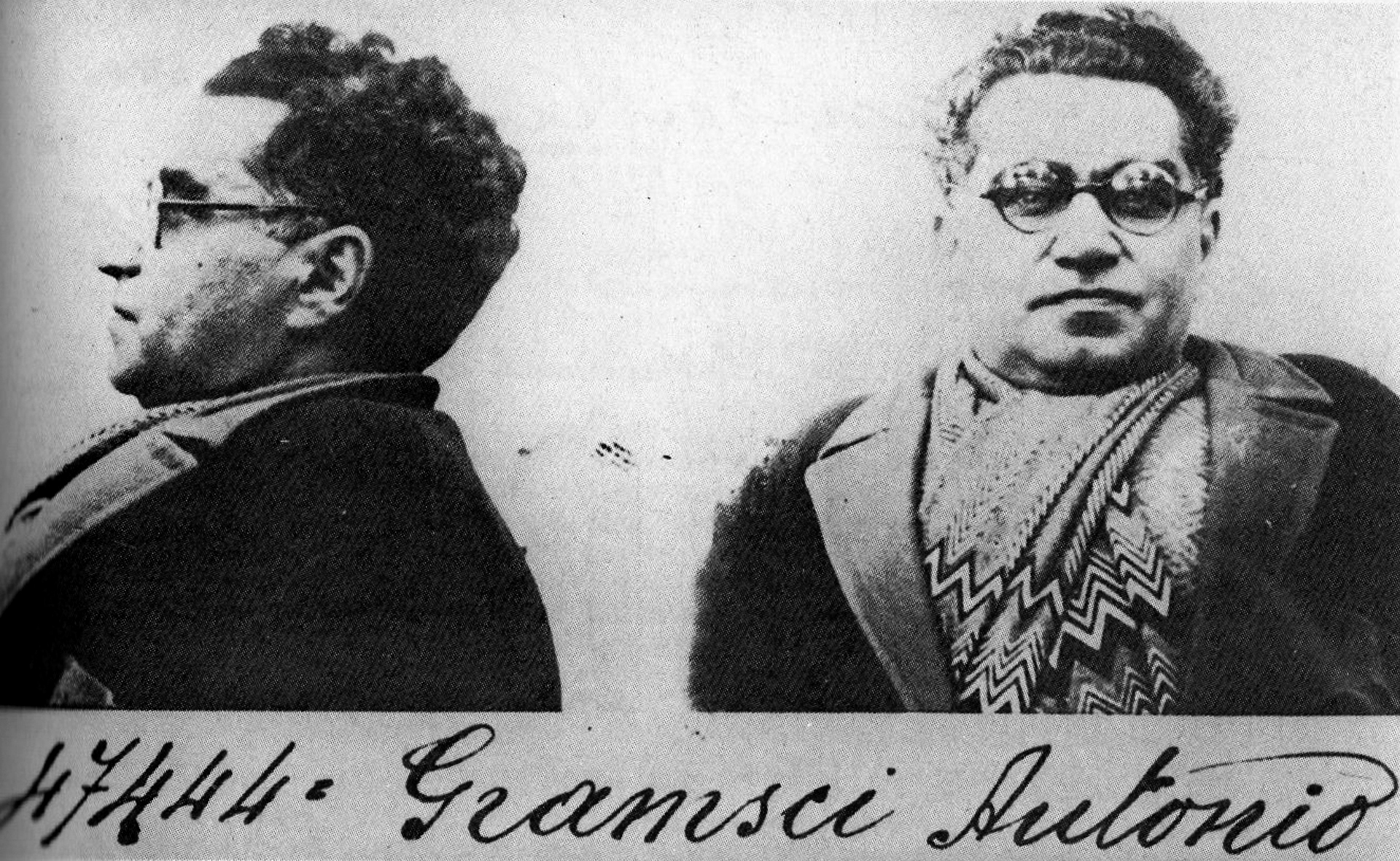

Fascism in Italy during the 1920s in 1930s has been often referred to as a form of “imperfect totalitarianism”, primarily owing to the continued presence of the monarchy and the Church, both of which exerted some influence (albeit minimal) in the affairs of the state. It also seemed to tolerate modernism far better than Nazi Germany or the Soviet Union. Nevertheless, it must not be forgotten that it was a tyranny. Opponents of the regime, including a number of intellectuals were forced to leave Italy or suffered internal exile or imprisonment, sometimes leading to death, as in the case of the politician and philosopher Antonio Gramsci. Gramsci, founder of the Italian Communist Party and a member of Parliament, was arrested on the night of November 8, 1926. Charged with conspiracy against the state, instigating civil war and subversive propaganda, he was sentenced to twenty years in prison. The conditions in his cell severely weakened his health, and after numerous and futile attempts to have him released, he was finally allowed to leave prison on grounds of ill health in 1935. The series of essays Quaderni del carcere [Prison Notebooks] were written between 1929 and 1935, and although written unsystematically, they are considered a highly original contribution to 20th-century political theory.

Antonio Gramsci in prison, 1933

bw. photo, exhibition print

Archivio Centrale dello Stato, Rome

Mussolini claimed in April 1933 that “a state cannot create its own literature.” He went on to summon the writers “to prepare a theater for the masses, a theater able to accommodate 15,000 or 20,000 persons [that will] stir up great collective passions, be inspired by a sense of intense humanity, and bring to the stage that which truly counts in the life of the spirit and in human affairs.” His appeal did not fall on deaf ears. Entitled 18 BL (after the model name of its truck-protagonist), the spectacle was the featured event of the 1934 Littoriali della Cultura e dell’Arte, Fascism’s youth Olympics of art and culture. The subtitle of the grandiose production, Teatro di Masse – Teatro per Masse [Theater of Masses – Theater for Masses] was no coincidence. The collaborative creation of seven young writers and a film director, 18 BL brought together two thousand actors, fifty trucks, eight bulldozers, four field- and machine-gun batteries, ten field radio stations, and six photoelectric brigades in a stylized Soviet-style representation of the Fascist revolution’s past, present, and future. But however titanic its scale, its ambitions were even greater: to institute a theater of the future, a modern theater of and for the masses that would end, once and for all, the crisis of the bourgeois theater. BL18 was an experimental mass spectacle that was engaged both in negotiating the Fascist revolution’s relationship with its Soviet predecessor and in forging an alternative to Bolshevism’s mechanical mass subject—the Fascist ideal of “metallized man.” 18 BL elaborated a total concept of spectacle founded on Fascism’s wholesale theatricalization of Italian life.

The mass spectacle 18BL, 1934

bw. photo, exhibition print

“18 BL: Spettacolo di masse per il popolo,” Gioventù fascista 4, no. 8 (15 April 1934) / Blasetti Archive

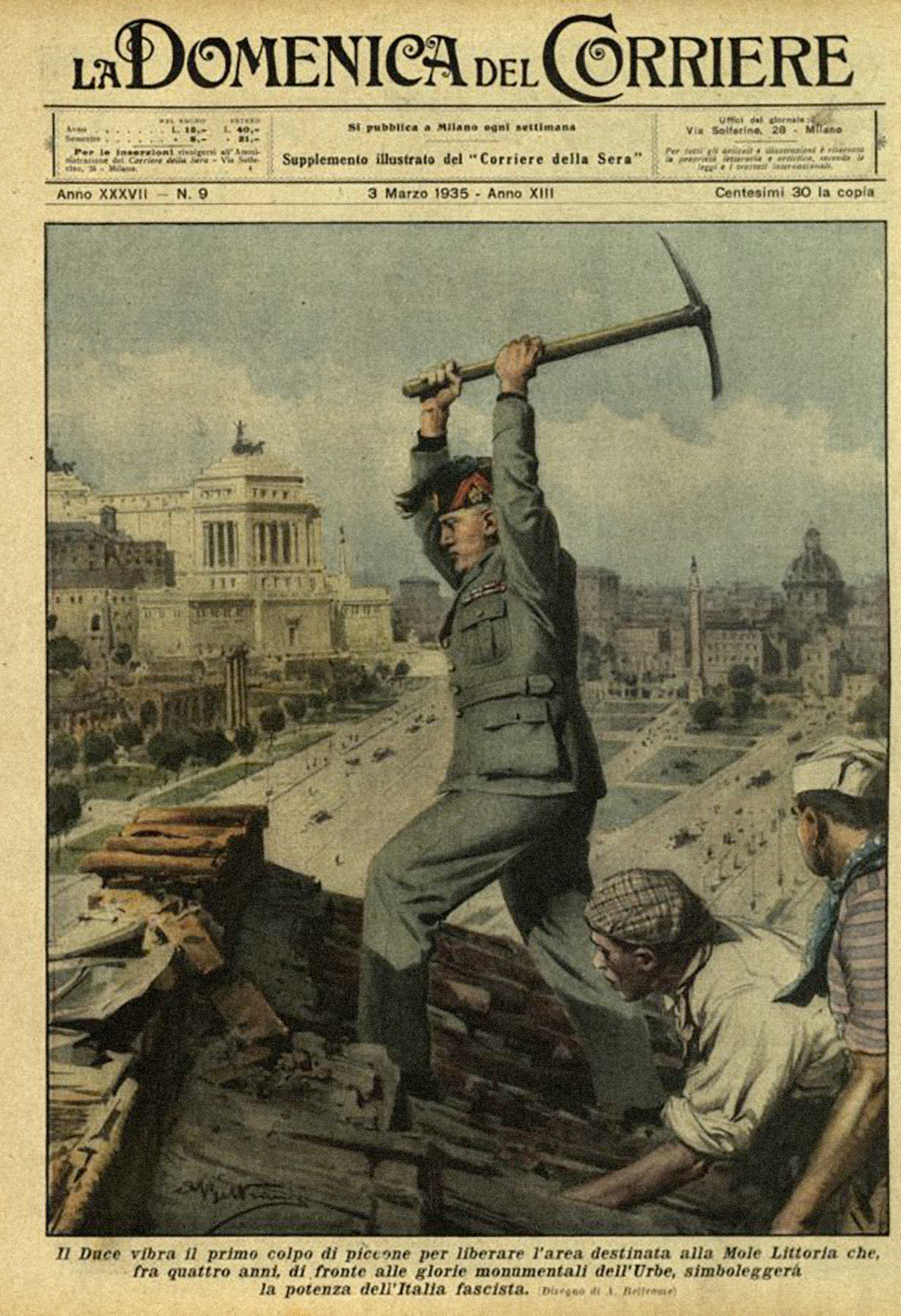

Fascism’s fascination with theater resulted in major urban modernization developments, turning the City of Rome (and other cities in Italy) into a back-drop for the Duce’s performance as the “New Augustus.” In a speech in 1925 Mussolini declared: “In five years Rome must be seen to be marvelous to all the people of the world: vast, ordered, powerful, as it was in the first Augustan Empire.” The Plan of 1931, produced under Mussolini’s eye by a committee representing divergent views, was based on five major points. First, archaeological sites (especially those of the Augustan era) were central to the presentation of Fascism as a revival of the Empire. Second, a triumphal way, the Via dell’Impero would have to be created to link the Piazza Venezia with a new road to Ostia and the sea (Via del Mare). Third, a monumental development to the North (housing, sports arenas, new roads and bridges) should form a gateway to the modern city—this became the Foro Mussolini. Fourth, the southern areas along the Via del Mare would need a great feature which turned out to be the exhibition city of EUR. Fifth, the working class should be moved out of the city center into new districts in the west, east and south. This amounted to a dramatic reshaping of the urban landscape. Fascist urbanism relied heavily on sventramenti, the destruction of existing buildings. The maneuver’s aim was to liberate ancient structures from successive additions and destroy the idea of Rome as a palimpsest of historical layers. The rhetoric of liberation was frequently deployed, with Mussolini claiming that “the millennial monuments of our history must loom gigantic in their necessary solitude.” Sventramenti created a visible, direct connection between modern and ancient Rome, it also systematically obliterated traces of low-income life in Rome. One of the “liberated” symbolic sites of the regime was around the Mausoleum of Augustus, where—among other projects—the Mole Littoria was planned. A truly pharaonic building, over 200 meters high, resting on a square platform of 250 by 250 meters, the Mole Littoria was intended to eclipse any other high-profile building inside Rome, including St Peter’s Basilica. In October 1934, Mussolini made a speech outlining the project and, seizing a pickaxe, cried “And now let the pickaxe speak!”. The image (in film, photograph and painting) of Mussolini energetically wielding a pickaxe proved an effective means of projecting the demolition of the old Rome as a “revolutionary” Fascist act. The iconography of the pickaxe and the pneumatic drill became almost as strong as that of the dagger and machine gun in the monumental art of the period.

Mussolini starts demolition work for the Mole Littoria, October 1934

bw. photo, exhibition print

Farabollafoto, Rome

“The Duce is the first to use the pickaxe to liberate the area for the Mole Littoria”, 1935

exhibition print

La Domenica del Corriere (March 3. 1935)

Pietro Canton, View of the Spina di Borgo under demolition, 1937

bw. photo, exhibition print

Archivio Fotografico Luce, Rome

The mythical status of the City of Rome and its symbolic resonance had been part of the Italian, indeed the European, psyche since the time of the Roman Empire. By the time of the war in Ethiopia (1935–1936) and the creation of the new Italian empire, the concept of romanità had become central to Fascist propaganda. In unison with the literal unearthing of Italy’s past, the regime set about constructing the new Italy, both practically and metaphorically. Romanità found direct expression in the pared-down columns and triumphal arches of such monumental neoclassical edifices as Marcello Piacentini’s Palazzo delle Corporazioni in Rome. The paintings and sculptures of these years reflected the influence of romanità when they formed an integral part of architectural public commissions, such as the heroic statuary of the Stadio dei Marmi [Stadium of the Marbles] around the Foro Mussolini (designed by Enrico del Dobbio), or in the large-scale murals in public buildings such as ministries, post offices and railway stations.

Enrico del Dobbio, Stadio de Marmi [Stadium of the Marbles], Foro Mussolini, 1928–32

bw. photo, exhibition print

photo by Gianni Galassi © Gianni Galassi

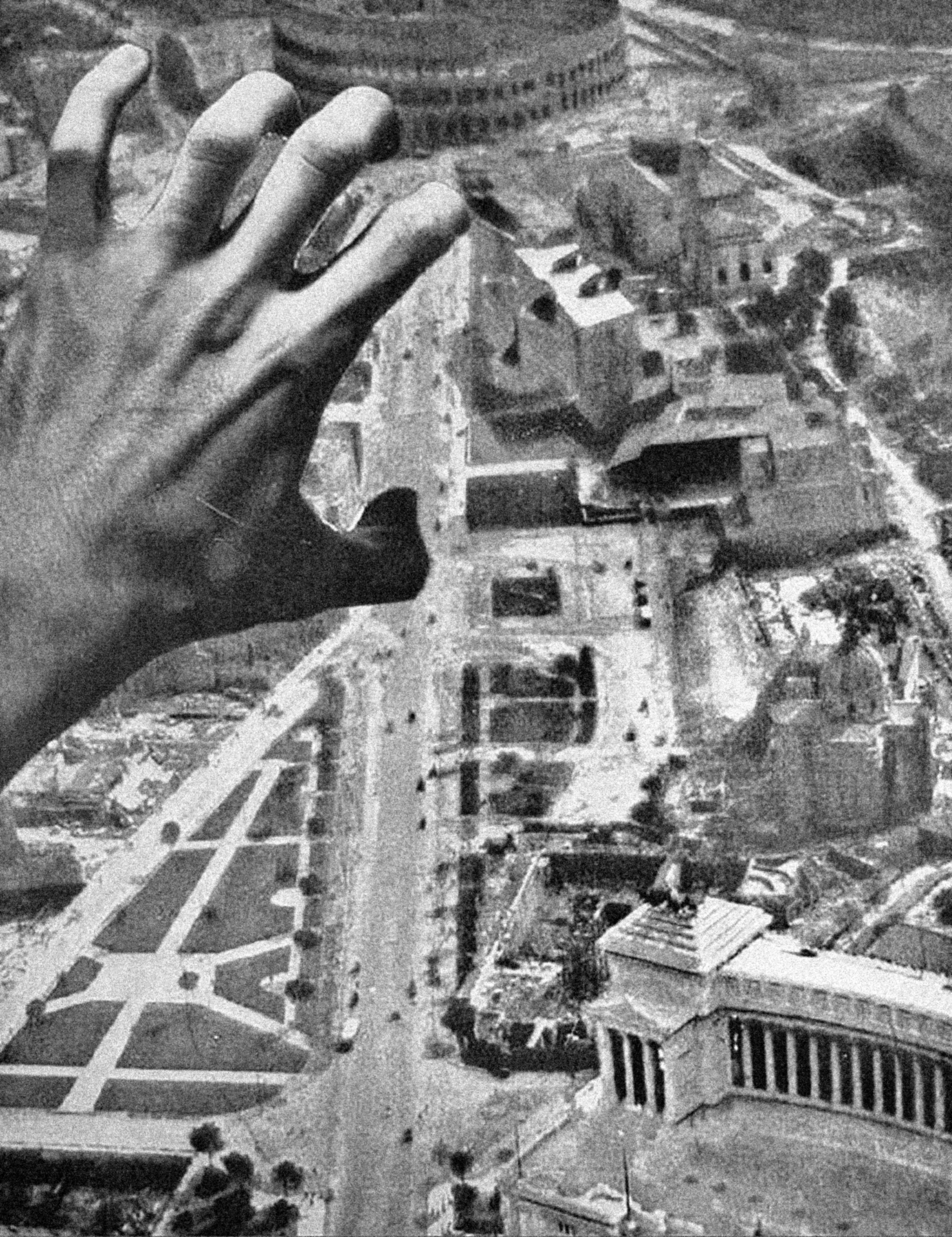

The various plans for the construction of a new “Imperial Rome” were surrounded by an open public debate. However, there was no question about the what, only about the how, as presented by the photo “Questo non lo permetteremo” [We Will Not Allow This] by Pietro Maria Bardi. Writer, curator, art critic Pietro Maria Bardi ran an art gallery financed by the National Fascist Syndicate of Fine Arts in 1930. In 1931 he wrote a famous report on architecture for Mussolini, and promoted the Italian Exhibition of Rationalist Architecture. Starting in 1933, together with Massimo Bontempelli, he directed the magazine Quadrante, dedicated to arts and architecture, with the collaboration of Le Corbusier and Giuseppe Terragni, among others. The short-lived cultural journal Quadrante transformed the practice of architecture in Fascist Italy. Over the course of three years (1933–36), the magazine agitated for an “architecture of the state” that would represent the values and aspirations of the Fascist regime, and in so doing it changed the language with which architects and their clientele addressed the built environment. The journal sponsored the most detailed discussion of what should constitute a suitably “Fascist architecture.” Quadrante rallied supporters and organized the most prominent practitioners and patrons of Italian rationalism into a coherent movement that advanced the cause of specific currents of modern architecture in interwar Italy. Starting in 1937, Bardi began to oppose Mussolini’s official architecture, in a controversy that became notorious in the Italian sociocultural milieu. After WWII he relocated with his wife, the architect Lina Bo Bardi, to Brazil, and eventually became the founding director of the São Paulo Museum of Art.

Pietro Maria Bardi, “Questo non lo permetteremo” [We Will Not Allow This], 1934

bw. photo, exhibition print

Quadrante 18 (October 1934)

The politics of Italian rationalism was exceptional among the interwar movements in modern architecture, since most were associated with progressive or revolutionary politics on the Left. Rationalism was the only movement of modern architecture that sought to represent the political values of a Fascist regime. Polemicists from all camps saw architecture as part of a broader project of cultural renewal tied to the political program of Fascism, and argued that architecture must represent the goals and values of the Fascist regime. While exceptional, the case of a modern movement’s outspoken engagement with radical right-wing politics provides excellent insights into the (sometimes) authoritarian tendencies of international modernism. One of the seminal works of rationalist architecture in Italy in the mid-1930s is the Casa del Fascio, designed by Giuseppe Terragni. A founding member of the Fascist architects’s group Gruppo 7, Terragni fought to move architecture away from neo-classical and neo-baroque revivalism. Nor did he shy away from propaganda work; he participated in the Mostra della Rivoluzione Fascista [Exhibition of the Fascist Revolution] in 1932. The construction for the Casa del Fascio began in July 1933, after many years of design revisions and construction delays, and ended in 1936, when it was inaugurated as the local branch of the National Fascist Party. Terragni created a small but remarkable group of designs; most of them were built in Como. During WWII, he was sent to the Eastern Front, where he suffered a nervous breakdown when the Italian contingent near Stalingrad. He returned to Como where he died in 1943, only 39 years old. Casa del Fascio currently houses the Command of the VI Legion of the Italian Finance Police, but in February 2017 a petition was launched proposing its re-use for cultural purposes, namely as a museum of rationalism and abstract art.

Giuseppe Terragni, Casa del Fascio, Como, 1932–1936

bw. photo, exhibition print

photo by Lettkemann / wikimedia commons

Giuseppe Terragni, Casa del Fascio, Como, during a mass rally on May 5, 1936

bw. photo, exhibition print

Quadrante 35/36 (September–October 1936)

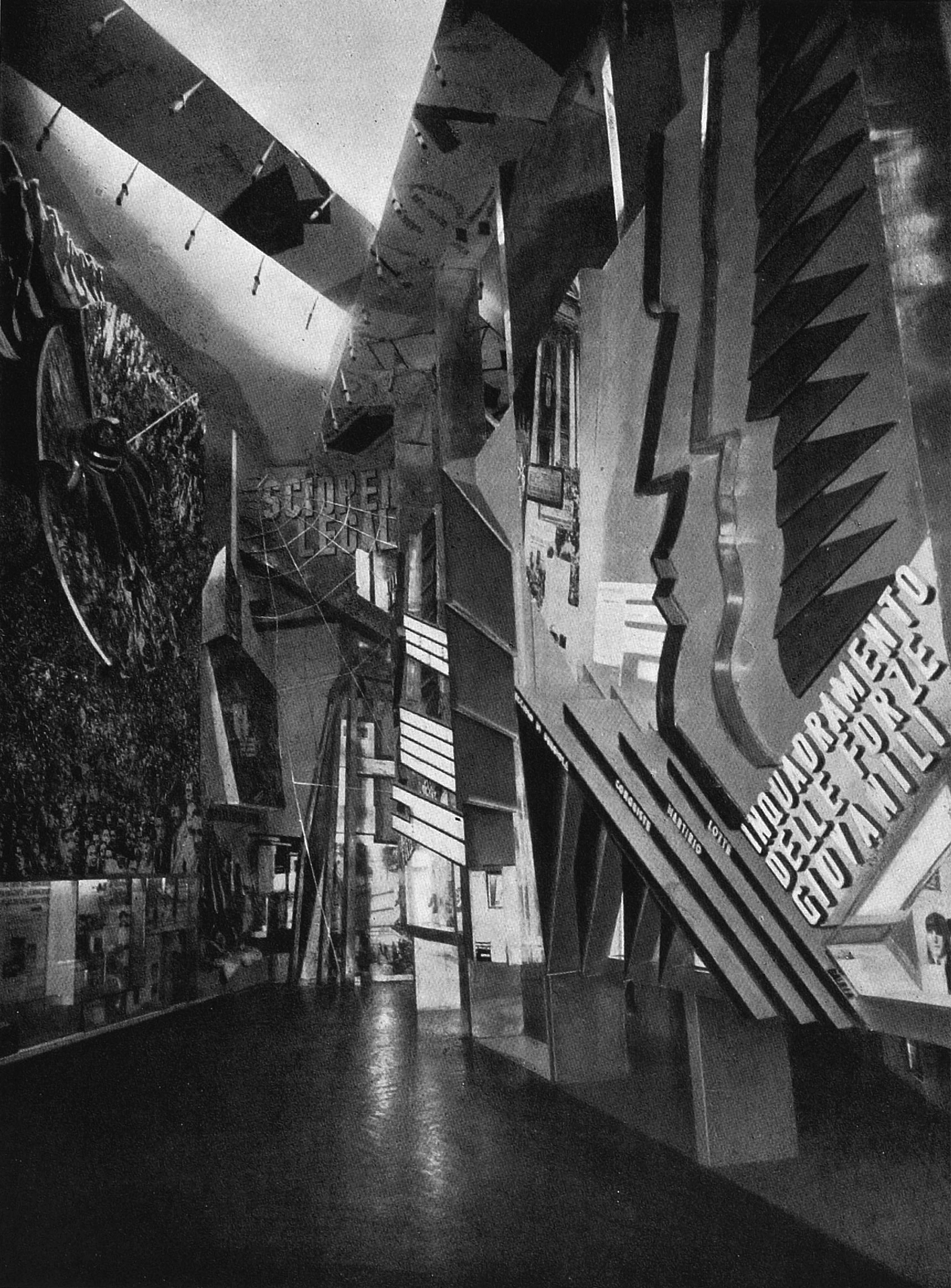

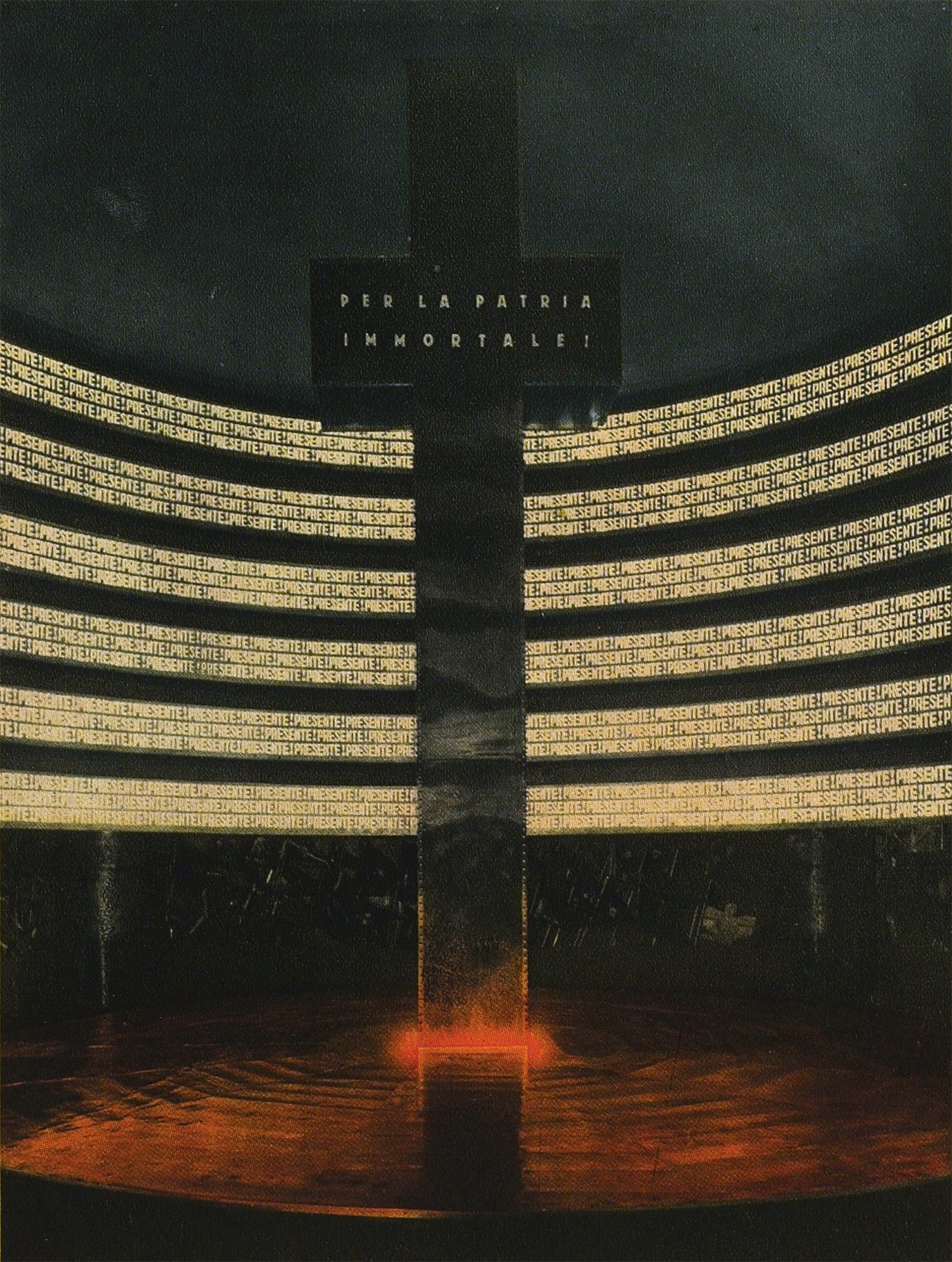

Modernity was the key word to describe the Mostra della Rivoluzione Fascista [Exhibition of the Fascist Revolution], a monumental exhibition held in 1932 at the Palazzo delle Esposizioni in Rome, which—through documents and special installations—celebrated the 10th anniversary of Mussolini’s March on Rome and rise to power. The exhibition was never conceived as an objective representation of the facts or as being solely based on the exhibiting of historic documents, but as a work of Fascist propaganda to influence and involve the audience emotionally. For this reason not only historians were called in to assist in the exhibition, but also exponents of various artistic currents of the era, such as Mario Sironi, Enrico Prampolini, Gerardo Dottori, Adalberto Libera and Giuseppe Terragni. Painters, sculptors and architects were encouraged by the Duce himself to “create a contemporary style, very modern and audacious, without melancholic references to the decorative styles of the past.” And indeed, the architectural interiors of the exhibition, heavily influenced by futurism and Russian constructivism, were the measure of its revolutionary theme. Through modern design and the ingenious use of photomontage and reliefs, especially in Terragni’s Sala O [Room O] dedicated to the year 1922, the artists responded to the organizers call for “an architectonic … scenographic style, which involves the atmosphere of our times.” The sequence of the exhibition situated the history of Fascism in the historical context of Italian civilization. The ideological message and the identification with Italy’s and Rome’s former grandeur, were implicit if not explicit. Despite its international avant-garde inspiration, the design of the exhibition was co-opted by Fascism as a representation of “the expressive vigor of the most felicitous period of Italian art.”

Entrance of the Mostra della Rivoluzione Fascista [Exhibition of the Fascist Revolution], Rome, 1932

bw. photo, exhibition print

Archivio Centrale dello Stato, Rome

Mostra della Rivoluzione Fascista [Exhibition of the Fascist Revolution], Rome, Sala O [Room O], designed by Giuseppe Terragni, 1932

bw. photo, exhibition print

Archivio Centrale dello Stato, Rome

Mostra della Rivoluzione Fascista [Exhibition of the Fascist Revolution], Rome, Sala U, Sacrario dei martiri [Room U, Shrine of the Martyrs], designed by Adalberto Libera and Antonio Valente, 1932

colored photo, exhibition print

Archivio Centrale dello Stato, Rome

Mussolini visits the exhibition Mostra della Rivoluzione Fascista [Exhibition of the Fascist Revolution], Rome, 1932

video, 1’10”

Archivio Luce, Rome

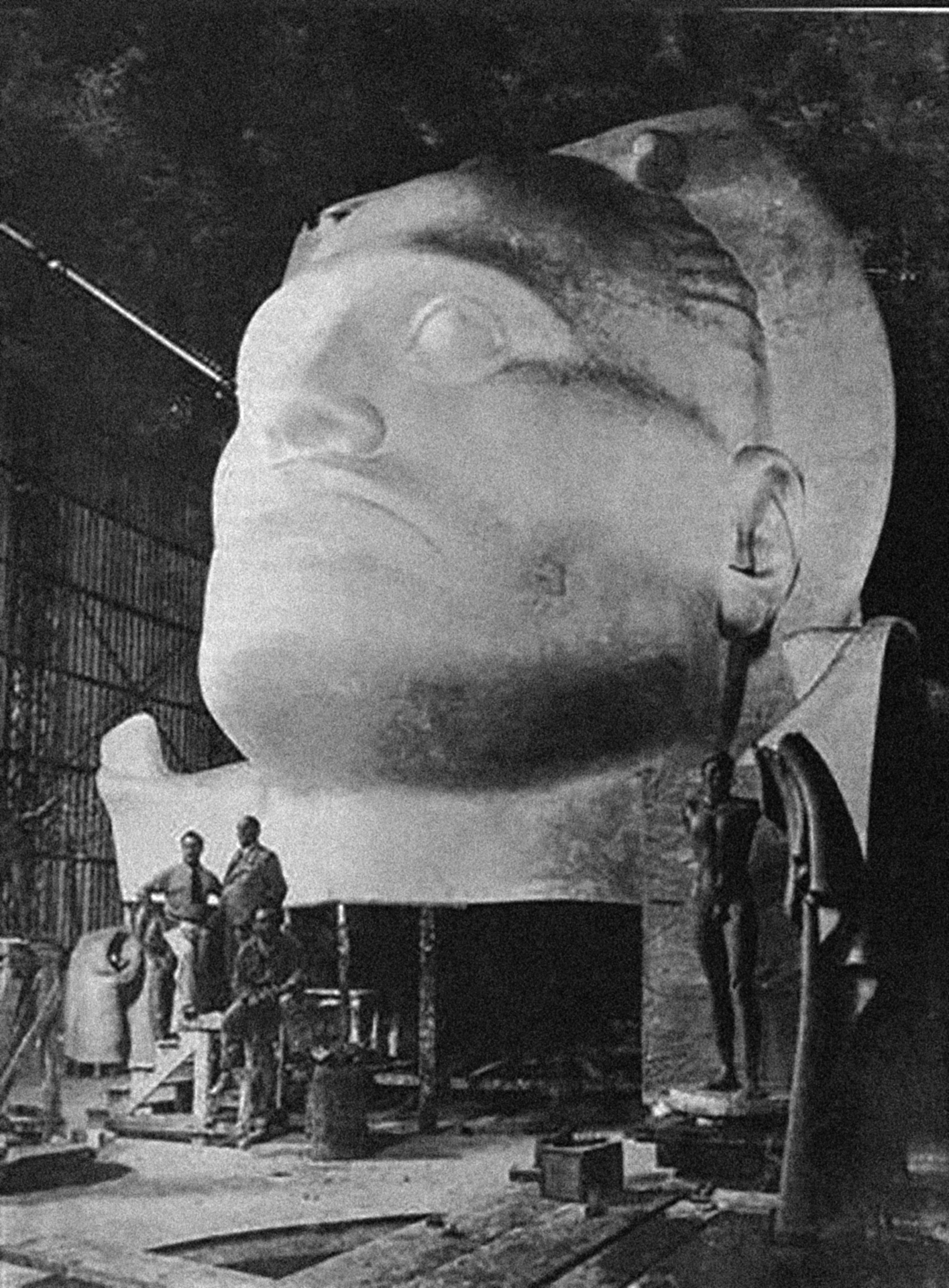

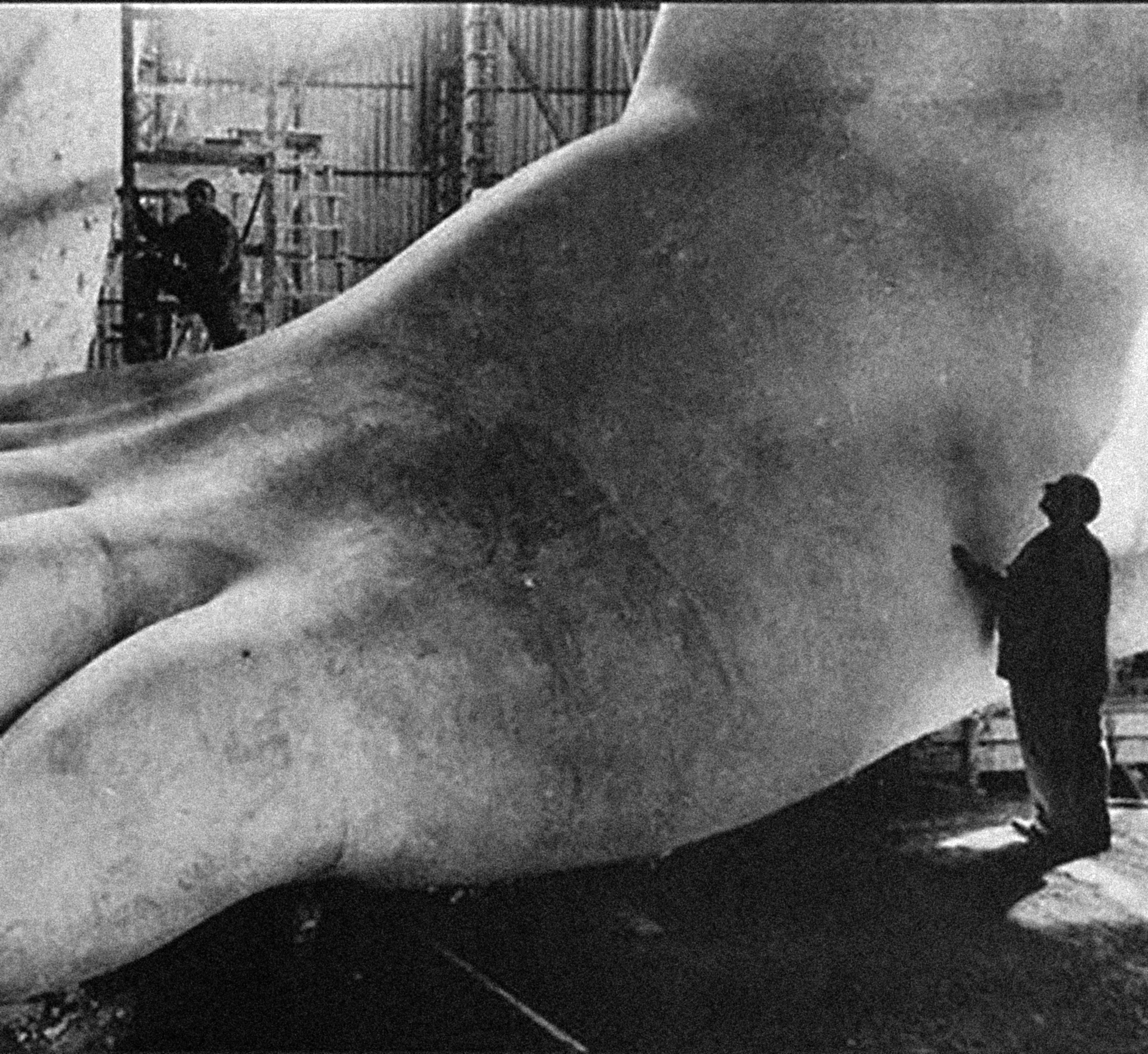

The Fascist symbolic armory consisted of black shirted uniforms, dagger salutes, feats of aviation, and colonial exploits (not to mention the feats of “corporatism”). But much of Fascist symbolic politics did revolve around the Duce, who spoke to the people from balconies and in regular radio addresses. Explaining Mussolini’s prominence as the ideal aesthetic subject, one art historian at the time noted his effortless negotiation between past glories and prospective challenges: “his greatness consists in the superlatively modern universality of his mind, which extends from historical exegesis to the most arduous problems of the future.” The greatness was very often meant literally—in spite of the short stature of Mussolini. The developing plans for the “New Rome” were to have included an 86-meter high statue of the Duce, designed by Aroldo Bellini, as an attempt to personify Fascism by transforming ideology into material form. A public announcement of its creation was made in the wake of the conquest of Ethiopia, though the idea of a gigantic statue at the Foro Mussolini was the fruit of several years’ work. The Statue of Liberty provided the main point of reference, both in terms of global renown and engineering. Most probably due to lack of funds, only the head and the limbs were ever completed, (at least both feet and one knee were cast beside the head of the Colossus). The statue’s facial features were delineated, so as not to create a precise representation of Mussolini but merely to evoke his image through a generic Herculean figure, with the intention that future generations should read into the mythologized statue a sublimated and deified ideal of the Duce. The statue was meant to be an updated version of the Colossus of Nero and to depict “the Likeness of He whom we all worship as the Genius of our country and of our race”. The initial proposal to locate the colossus on Monte Mario was revised to bring the statue closer to the Foro Mussolini, so that it would in fact stand directly behind Mussolini’s platform, a materially idealized figuration of Fascism animated by the leader and crowd below, as if themselves sanctified in front of the colossal new deity.

Aroldo Bellini, The head and the limbs of the monumental bronze statute Fascism, 1934

2 bw. photos, exhibition prints

Archivio Centrale dello Stato, Rome

The heroic, war-mongering, machine-obsessed initial phase of futurism ended with Italy’s entry into the First World War in 1915, and the period of so-called second futurism [Secondo Futurismo] began with Giacomo Balla’s and Fortunato Depero’s Ricostruzione dell’universo futurista [Reconstruction of the Futurist Universe] in 1915. During the 1920s second futurism was heavily influenced by a machine aesthetic. By the early 1930s a large contingent of futurist painters had begun to refer to their work as Aeropittura. The early interest in the motor car was replaced by a fascination with aircraft, with flight, and with extraterrestrial fantasy. In the Manifesto dell’Aeropittura futurista [Manifesto of Futurist Areopainting], published in 1929, the futurist artists—including Giacomo Balla, Marinetti, and Fillia (Luigi Colombo)—launched the idea of an art linked to the most exciting aspects of contemporary life. During the next five years they published manifestos devoted to, among other things, aero-architecture, aero-sculpture, aero-ceramics, and aero-music. The following years witnessed significant developments in each area and the creation of two more disciplines: aero-perfume and aero block printing. The themes of speed and flight were depicted by the Aeropainters in two ways: as cosmic analogy, or simply by vertiginous aerial views of planes swooping down over the landscape. During the 1930s, the Aeropainters, supported by the poet and cultural impresario Marinetti, sought to align themselves with the Fascist regime; and the Duce became an important subject for Aeropittura—for instance, as an “aviator”. The close relationship between the conquest of the air and warfare was not lost on the futurists, and the wars in Ethiopia and Spain provided them with up-to-date subject matter. The relationship between the futurists and Fascism came to a head in 1937, when a polemic exploded between the Milanese bimonthly Il Perseo and the review Artecrazia run by the futurist critic Mino Somenzi. The anarchic, modern and arbitrary nature of futurism was attacked for being fundamentally un-Italian and anti-fascist.

Report of the illustrated supplement of Pesti Napló on the elections in Italy, 1934

“Si, Si, Si! – Yes, Yes, Yes! Such huge election posters called on the people of Rome to vote for Mussolini during the elections; the vote ended with a huge victory for Mussolini.”

exhibition cover

Pesti Napló Képes Melléklete [Illustrated Supplement of Pesti Napló], April 1, 1934 / Arcanum

Giacomo Balla, Filippo Marinetti; Luigi Colombo, et. al., Manifesto dell’Aeropittura futurista [Manifesto of Futurist Areopainting]

Futurismo, 2:58, Roma, November 12, 1929

kiállítási nyomat

Accademia della Crusca, Florence

Alfredo Ambrosi, Aeroritratto di Mussolini aviator [Aeroportrait of Mussolini, the Aviator], 1930

oil on canvas, exhibition print

private collection, Milan

Gerardo Dottori, Rittrato del Duce [Portrait of the Duce], 1933

oil on canvas, exhibition print

Civiche Raccolte d’Arte, Milan

Renato Bertelli’s Continuous Profile is one of innumerable portraits of the Duce, yet, it is the most extraordinary one. A cylindrical shape with a brilliant static-dynamic effect, the bust incorporates futurist principles as enunciated by Boccioni regarding the curved line. Throbbing yet utterly still, the sculpture conjures up at once the gyration of some mechanical contrivance and—equally apparent to an Italian public—ancient depictions of Janus (the Roman god of beginnings, transitions, and time itself). Bertelli patented the work—in anticipation of “iconographic consumerism”—and mass-produced it in materials from terra-cotta to aluminum to marble. The head of the Duce thus “rotated” in Fascio houses, offices and private homes (not only in Italy). Apart from creating one of the most iconic sculptural representations of the Duce, Bertelli did not frequent fascist political and intellectual circles and kept himself away from the world of clients. Today’s critics debate whether this inventive modernist work can be freed from the legacy of the time, and regard it as the cornerstone of second futurism.

Renato Bertelli, Profilo Continuo (Testa di Mussolini) [Continuous Profile (Head of Mussolini)] , 1933

bronze, photo reproduction

Mart, Museo di arte moderna e contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto

Beside the futurists, the other group of artists to seek official recognition from the Fascist Party was the Milan-based group Novecento Italiano. Motivated by a post-war “call to order”, the group was led by the art critic and intimate friend and biographer of Mussolini, Margherita Sarfatti. The group wished to take on the Italian establishment and create an art associated with the rhetoric of Fascism, and was joined by former futurists, like Gino Severini, or Carlo Carrà. By 1932, its work—as represented by its most prominent member, the painter Mario Sironi—did correspond to the ideas of a Fascist art as expressed by Giuseppe Bottai. It combined elements of tradition and modernity; and it was monumental, with an innate sense of form combining both archaic and classical elements. Despite their endeavors to be aligned with Fascist ideology, by the early 1930s Mario Sironi and the group were being attacked by the intransigent factions within the party, led by Roberto Farinacci, the Party Secretary, who criticized their “deformed” and exaggerated figures, using these as evidence of “foreign” and “cosmopolitan” sympathies. These attacks were aggravated by the breakdown of Sarfatti’s personal relationship with Mussolini. In addition, her emphasis on modernity began to sit uncomfortably with certain members of the expanded group itself. The unity of the group depended much on Sarfatti. When she was distanced from Mussolini (in part due to the anti-Semitic ordinances of 1938), and emigrated to France (and later to Uruguay and Argentina), the group fell apart and was formally disbanded in 1943. Sarfatti returned to Italy only in 1947, after the war.

Margherita Sarfatti with the painters of the Novecento Italiano group at the Venice Biennial, 1930

bw. photo, exhibition print

Mart, Museo di arte moderna e contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto / Archivio del ’900

The disintegration of the Novecento movement coincided with Mario Sironi’s rejection of easel painting in favor of large-scale mural art. Influenced by the experience of the Mostra della Rivoluzione fascista and by the propaganda efficacy of modern Mexican mural painting, Sironi claimed that the ultimate function of painting was social and didactic. Without promoting one particular style, he called for mural art to convey the Fascist ideology through suggestive and evocative allegories, which would allude to such universal themes as italianità, nation, work, and the family. He proposed the reevaluation of traditional techniques, such as stained glass, fresco and mosaic; with these modern artists could communicate to the masses without compromising their artistic integrity. Sironi reiterated these ideas in his Manifesto della Pittura Murale [Manifesto of Mural Painting] which was signed in 1933 with Carlo Carrà, Massimo Campigli and Achille Funi, who had all, like him, been members of Novecento Italiano. Sironi saw a chance to make his ideas reality at the 5th Milan Triennale in 1933. A section of the exhibition was devoted to mural painting and monumental sculpture and reliefs, and Sironi invited more than thirty artists—including Giorgio de Chirico, Gino Severini, and Carrà—to decorate the walls of Palazzo dell’Arte, the main venue for the Triennale di Milano. The artists were given no precise subjects but either left to their own devices or simply asked to show “Italy in her various manifestations of work, sport, study, and family life”. Sironi’s objective was to convey the heroism of Italian civilization through what he called a “rediscovery of the classical”. The 1933 Triennale proved to be highly controversial. The rationalist architects denounced it as anachronistic, while hardline critics accused the artists of being “foreign” and “Bolshevik”. The Triennale was accused of being “anti-Rome”, of willfully excluding “any object or any decoration of a classic Roman style”. Given the controversy and the ephemeral nature of the exhibition, all the murals except for Severini’s mosaic Le Arti [The Three Arts] were destroyed or painted over. The Fascist policy of tolerance, however, allowed all the artists involved in the Triennale to continue working. Sironi’s vast mural L’Italia tra le Arti e le Scienze [Italy Between the Arts and the Sciences] for the Great Hall of Rome University and the allegorical mosaic Italia Corporativa [Corporative Italy], conceived for the Sixth Triennale in 1936 and shown in the Italian pavilion at the Exposition Internationale in Paris in 1937, both allude to Italy’s recent victory in Ethiopia and the symbolic union of contemporary Italy with its imperial past.

Mario Sironi, L’Italia tra le Arti e le Scienze [Italy Between the Arts and the Sciences], 1935

fresco, exhibition print

Sapienza University of Rome

Gino Severini, Le Arti [The Three Arts], 1933

mosaic, reproduction

Fondazione La Triennale di Milano

Artistic pluralism, favored by the moderates within the regime, was most clearly visible in the national Quadriennale exhibitions held at the Palazzo delle Esposizioni in Rome from 1931. The 1935 Quadriennale incorporated both the work of younger artists and a number of one-man shows devoted to the work of established artists, such as Severini, Carrà and Giorgio de Chirico. The Fascist regime’s capacity to absorb seemingly distant artistic positions is exemplified by the inclusion of the enigmatic works of De Chirico, which stressed the interrogative tensions and contradictions that can exist where tradition allies itself with modernity. De Chirico lived in Paris between 1925 and 1932, where he was associated with the group known as Italiani di Parigi [The Italians of Paris], and was discovered and praised by the surrealists. However, his relationship with the surrealists grew increasingly contentious, as they publicly disparaged his new work; by 1926 he had come to regard them as “cretinous and hostile”. They soon parted in acrimony. He returned to Rome in 1932, but went to the U.S. in 1936, from where he returned during the war to Italy. De Chirico cited three words “which I would like to be the seal of every work I have produced: namely, ‘Pictor classicus sum’—'I am a classical painter’.” The thought was anathema to the surrealists, who took unrestrained pleasure in attacking de Chirico for his later work, in which he celebrated the classical world and completely shied away from those elements in his style that were called proto-surrealist. He was greatly admired by many Fascists, even carried out occasional commissions for the Fascist Party, but always indignantly denied that his work had any connection to Fascist ideology. The paintings of de Chirico could almost be interpreted as anti-Fascist in mood, yet, interestingly, the regime was able to accommodate even dissonant voices.

Giorgio de Chirico, Self-Portrait in the Studio, 1935

oil on canvas, exhibition print

private collection

Mussolini, who originally had little regard for the cinema, found his interest aroused by the sound film revolution. He recognized that there were new opportunities for film to be used as a powerful cultural and propaganda instrument, which would replace the antiquated product of the silent film era. Mussolini’s first experience with sound film dated back to May 1927, when a team from the American newsreel company Fox-Movietone came to Rome to record the statement by the dictator. Very satisfied with the outcome he is reported to have said “Your talking newsreel has tremendous possibilities, let me speak through it in twenty cities in Italy once a week and I need no other power.” While the press and radio were highly politicized under Fascism, and all aspects of public life were subordinated to Fascist Party organizations, Mussolini initially allowed the cinema to develop in relative independence virtually free from political interference. In 1934 the Ministry of Popular Culture set up a film directorate, the Direzione Generale per la Cinematografia, and one year later the experimental film school, Centro Sperimentale die Cinematografia in Rome. Some members of the first generation of students were to become exponents of post-war neo-realism: Michelangelo Antonioni and Roberto Rossellini, among others. In contrast to Nazi Germany, the Fascist government of Italy valued the commercial successes of the film industry more highly than propagandistic expediency. In the hands of the Fascist regime the cinema became a dream factory similar to Hollywood. The cinema’s political function was almost exclusively used in newsreels, to assert and defend Fascist cultural ideas and ambitions. Cinegiornale, the official newsreel of the Istituto Nazionale LUCE had accompanied the development of the Fascist regime from its beginning, but the war in Ethiopia had awakened its full propagandistic potential. The company was since the early 1930s in state ownership. Appreciative of its supportive role in his African triumph, Mussolini laid the foundation stone of a new LUCE building in 1937; at the same time, Cinecittà, the largest studio complex in Europe, was founded in Rome. Feature film production was encouraged to stay out of politics, only occasionally reflecting on political affairs, but there were films that loyally mirrored Fascist ideology, such as Alessandro Blasetti’s Vecchia Guardia [The Old Guard, 1934].

“Film is the strongest weapon”: Mussolini lays the foundation stone of the new building of Istituto LUCE, Rome, 1937

bw. photo, exhibition print

Istituto LUCE, Rome

Istituto LUCE crew shooting a documentary during the Ethiopian War, 1935

bw. photo, exhibition print

Istituto LUCE, Rome

Alessandro Blasetti, Vecchia Guardia [The Old Guard], 1934

poster, exhibition print

Istituto LUCE, Rome

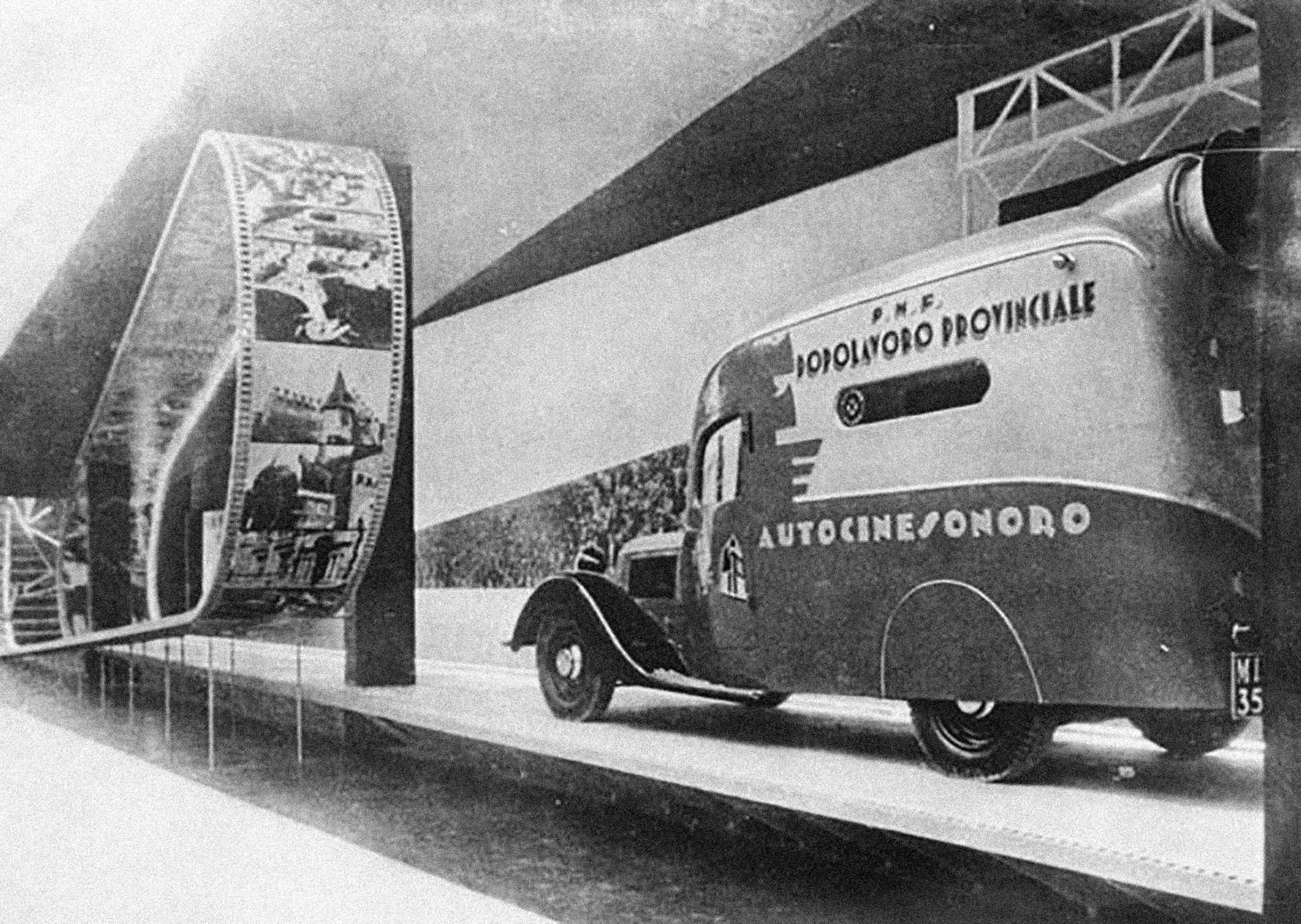

As in the working of the economy itself through the system of corporatism, the state (and the party) had to substitute for the autonomous forces of the market in providing mass culture. Fascist organization of leisure-time activities happened through the organization Opera Nazionale del Dopolavoro (OND). The Dopolavoro movement grew from 7.8 million members in mid-1933 to 16 million by 1935, and eventually to 20 million. The bureaucratic discipline imposed from above discouraged spontaneity. A popular pastime like bowls was made acceptable to the regime by inclusion in a framework of national, sponsored, competition. Popular festivities, such as carnivals, were also “appropriated” by the regime. Attempts to use the Dopolavoro as a medium for direct political indoctrination or cultural uplift were usually defeated by the failure of the middle-class Dopolavoro cadres to use a language which their audience could understand. The success of the Dopolavoro in achieving wide social coverage and a relatively high degree of voluntary participation, compared with other Fascist institutions, was purchased at the cost of the renunciation of any real role in political education. What the Dopolavoro could do instead was to encourage forms of social behavior which reinforced the stability of the existing order and to diffuse an image of the regime as benevolent. As recent scholarly investigations revealed, “the culture of the Dopolavoro legitimized Fascist dominion”, suggesting that it was successful precisely in the measure in which it renounced such ambitious aims.

A fascio made of grapes at the Grape Festival, Tuscany, 1931

bw. photo, exhibition print

Opera Nazionale Dopolavoro, Cinque anni di organizzazione (Rome: Opera Nazionale Dopolavoro, 1931) / Biblioteca Nazionale, Rome

Projection car shown at the exhibition Mostra del Dopolavoro, 1937

bw. photo, exhibition print

Opera Nazionale Dopolavoro, Cinque anni di organizzazione (Rome: Opera Nazionale Dopolavoro, 1931) / Biblioteca Nazionale, Rome