Attila József lived in the French capital between 1926 and 1927 as a student at Sorbonne University. It was here that he was introduced to the doctrines of Marx, Hegel and Lenin. In Paris, he not only made friends with the Hungarian émigrés living there, but also got to know some of the protagonists of French literary life; some of his poems in French were published in the newspapers there. His poetry demonstrates important changes during this period, with a stronger attraction to the grotesque. Although he had no direct contact with the surrealists, several scholars consider Attila József to be one of the Hungarian representatives of surrealism, while others associate his poetry more with the “pure poetry” [poésie pure] of Paul Valéry. There is no doubt, however, that the poetry of Arthur Rimbaud—whose poems he translated into Hungarian—had a great influence on him, and like the French poet, who was considered the “father of surrealism”, he was also immersed in the mysteries of the soul. In his case, however, this immersion was not through “artificial pleasures”, but the result of his all too real psychological-psychiatric problems.

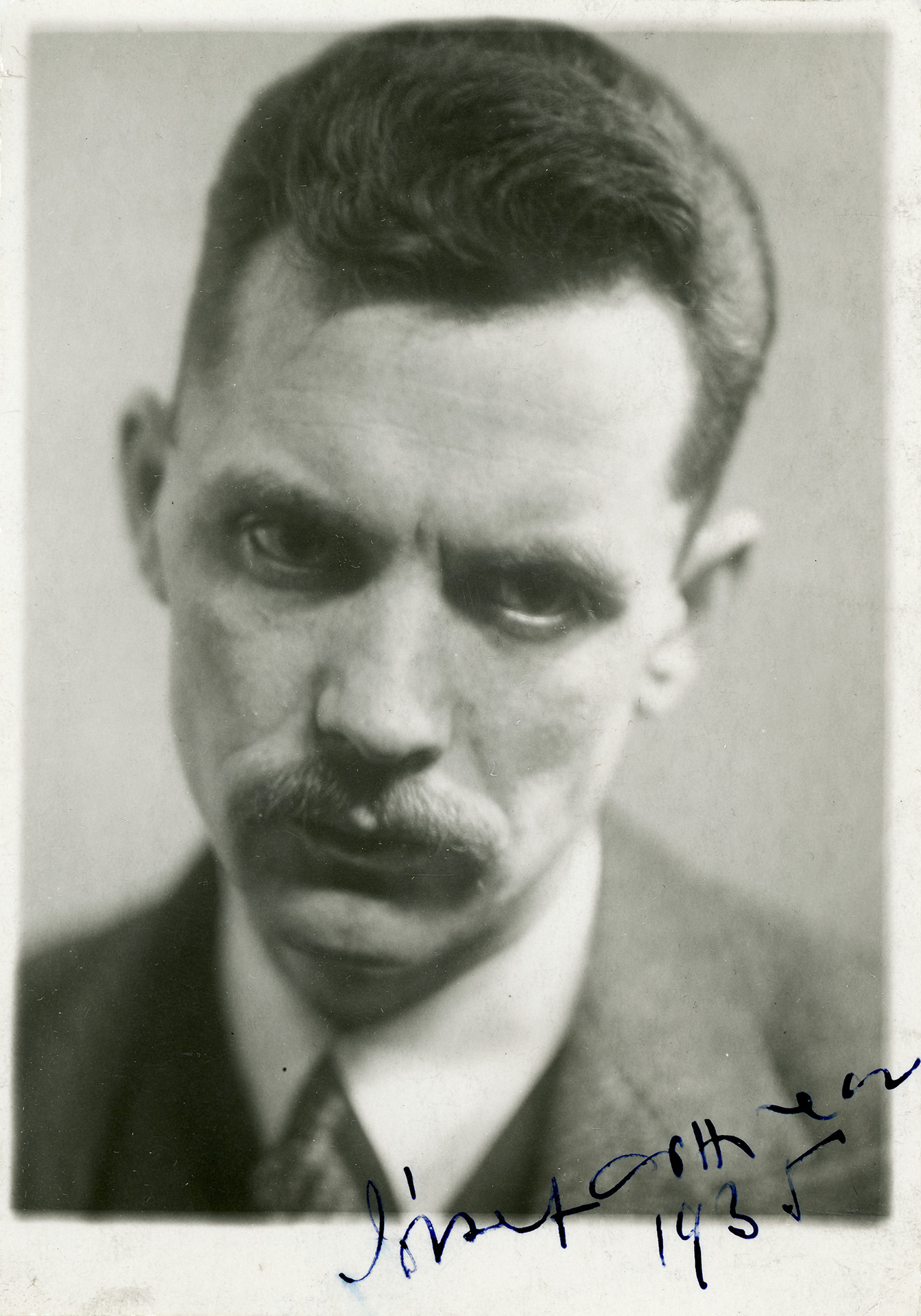

“Upon a branch of nothingness / my heart sits trembling voicelessly”. These words were written in 1933 and render a poetic anamnesis of a person whose ties with the outside world have been severed. In the critical literature that has sprung up round Attila József since his death, it has been hotly debated whether or not the psychoanalytical treatment which he received from 1931 did in fact contribute to the manifestation of his latent schizophrenia. (The exact psychology-psychiatric illness is the subject of further debate). Whatever the case, Freudianism became an important intellectual discovery for the poet. Not only did he try to blend Marx with Freud in an essay Hegel – Marx – Freud (1934), pointing out that economic interests alone do not decide the political allegiance of the individual or the masses, but he borrowed many words and concepts from the vocabulary of Freudian theory. His Freudianism was also a cause of his disapproval by the Communist Party, which—along with events in his personal life—made the poet more isolated and fragile than ever. The two-part poem, Reménytelenül [Without Hope, 1933] is an imprint of this state of mind, while it also shows the playfulness and surrealistic tendencies of his earlier work.

Without Hope

Slowly, musingly

I am as one who comes to rest

by that sad, sandy, sodden shore

and looks around, and undistressed

nods his wise head, and hopes no more.

Just so I try to turn my gaze

with no deceptions, carelessly.

A silver axe-swish lightly plays

on the white leaf of the poplar tree.

Upon a branch of nothingness

my heart sits trembling voicelessly,

and watching, watching, numberless,

the mild stars gather round to see.

In heaven’s ironblue vault ...

In heaven’s ironblue vault revolves

a cool and lacquered dynamo.

The word sparks in my teeth, resolves

– oh, noiseless constellations! – so –

In me the past falls like a stone

through space as voiceless as the air.

Time, silent, blue, drifts off alone.

The swordblade glitters; and my hair - -

My moustache, a fat chrysalis,

tastes on my mouth of transience.

My heart aches, words cool out to this.

To whom, though, might their sound make sense?

March 1933

translated by Frederick Turner & Ozsváth, Zsuzsanna

In the mid-1930s the Dimensionists were looking for a new artistic language that was applicable to the dramatically changing scientific world view. Meanwhile, the Surrealists wanted to expand their surrealist world revolution that originated from the depths of the soul to the whole world. Krisztián Kristóf’s exhibition in 2017; Empathic Landscape in the Trafo Gallery, presents a (pseudo-) scientific experiment and its psychological interpretation in parallel. The two works that are part of the OFF-Biennale were first presented at this exhibition. The starting point of the exhibition was a visual language based on improvisational graphical works that is closely related to the ISOTYPE visual language of the 1930s, the visual dictionary of Gerd Arntz and Otto Neurath. As Kristóf said in an interview: “These are visually set, schematic graphics so the improvisational energy is not wasted on graphical virtuosity but is focused on the content, the narrative scenes and the relationship between the characters.” The sheet films entitled Empathic Landscape apply this visual language, too: “I think that the title Empathic Landscape is both touching and ironic, since why would Mother Earth be empathic with us if we don’t give a shit about her? The enlargements of the title sheet film show a figure that moves large abstract structures attached to its limbs through pulleys as if it were a marionette. In my interpretation, this is the world view of the figure, presented as a landscape. It is an inner landscape, but the figure in the image is probably not aware of that. Living in the illusion of total power, seeing only its own enlarged, transformed image, it does not realize that it is only part of a closed system. This landscape is the nihilistic parody of the outer world. But I suspect that the most exciting landscapes of art history are also not about the environment, but the human relations to it, so eventually, they are about human nature.”