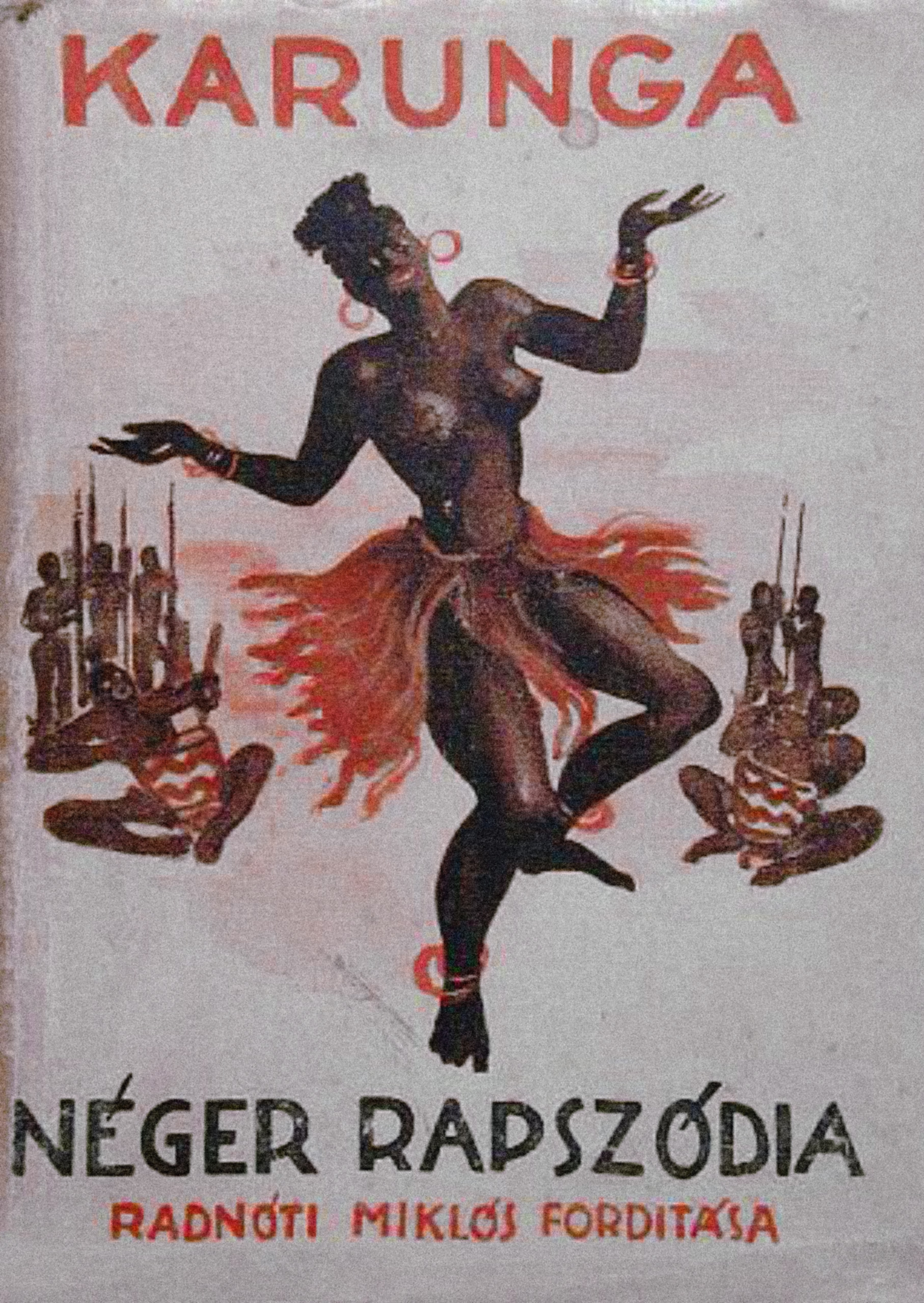

Attila József’s young poet friend, Miklós Radnóti visited Paris in the summer of 1931, when the French capital was buzzing with the Exposition Coloniale [Colonial Exhibition]. Europe was beginning to discover the art of Africa at the beginning of the 20th century, and this interest was still unabated in 1931. As Radnóti wrote to a friend, “There is now a great néger fever here in Paris and huge volumes of néger anthologies are being published.”* Radnóti visited the Exposition Coloniale on several occasions, and the exhibition got him interested in African literature and art. He wrote several “néger poems,” the best known of which is the Ének a négerről, aki a városba ment [Song of the Néger Who Went to Town, 1932]. In 1943–1944 he translated a volume of African tales, which, together with his previously unpublished translations of poems on similar themes, appeared in the volume Karunga a holtak ura, Néger rapszódia [Karunga the Lord of the Dead, Néger Rhapsody], in 1944, shortly before he was brutally murdered by Arrow Cross troops on the outskirts of Abda, a village in Western Hungary.

In fact, the Exposition Coloniale was an attempt to fire the “colonial imagination” by harking back to the ethnographic shows of the nineteenth century. However, after World War I, the depiction of the “savages” changed; the focus was now on the “civilizing mission” of the colonial masters and the “benefits” that colonialism brought for the subjugated peoples. The colonial exhibitions between the two world wars presented how the colonialist powers helped the colonized nations with modern infrastructure and education. Instead of the “savages” of the 19th-century world fairs, the cultures of the “natives” were on display. The aim was to communicate “colonial humanism” and the beneficial effects of the civilization process. The colonial exhibitions of the interwar period—Marseille in 1922, Wembley in 1924, Liège and Antwerp in 1930, Paris in 1931 and Chicago in 1933—as well as the national “trade exhibitions” held in Germany, Italy and Japan between 1922 and 1940 were enormous crowd pullers. At the British Empire Exhibition in Wembley (1924–1925), more than 27 million tickets were sold; at the Exposition Coloniale in the Bois de Vincennes (1931), more than 33 million. The colonial exhibitions “Paix entre les races” [Peace between the Races, Brussels, 1935), the British Empire Exhibition (Glasgow 1938), the Deutsche Kolonial-Ausstellung [German Colonial Exhibition, Dresden, 1939] or Mostra d’Oltremare [Overseas Exhibition, Naples, 1940] all tried to paint the picture of pacified empires and happy subjects.

The Exposition Coloniale in Paris drew fierce criticism from the anti-imperialist camp that organized its own counter-exhibition. The latter was initiated and financed by the Third Communist International. That the counter-exhibition, La vérité sur les colonies [The Truth about the Colonies] in the Palace of the Soviets, was hosted jointly by the French section of the Anti-Imperialist League and the French Communist Party is thus not surprising. Members of the African diaspora and Vietnamese activists were among those to take part, as was a group of surrealists centered around Louis Aragon. Colonialist politics was harshly criticized by a number of artists—also outside the circle of the surrealists. Even in a country like Hungary that did not have colonies, artists and writers understood that the problems they witness at home are closely linked to this problem.

*In Hungarian the word “néger” comes from the French “nègre”, but unlike its origin, during this period, it wasn’t derogatory and only meant “black man.”

Miklós Radnóti, Karunga a holtak ura, Néger rapszódia [Karunga the Lord of the Dead, Néger Rhapsody], 1944

cover design by Vera Csilag, Budapest: Pharos Publishing House

private collection, Budapest

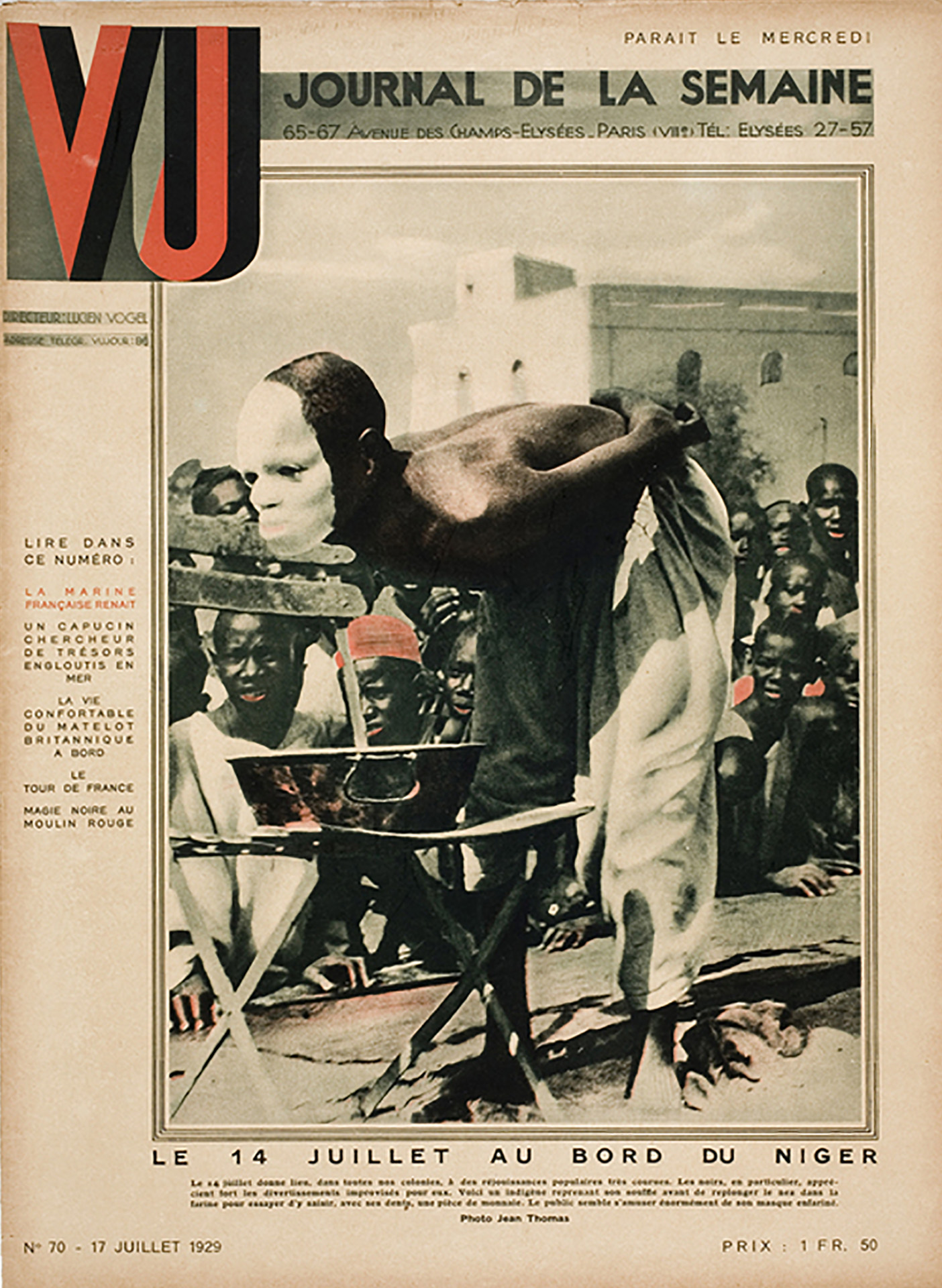

“Le 14 juillet au bord du Niger” [July 14 on the banks of the Niger], 1929

exhibition print

Vu. Journal de la semaine, July 17, 1929

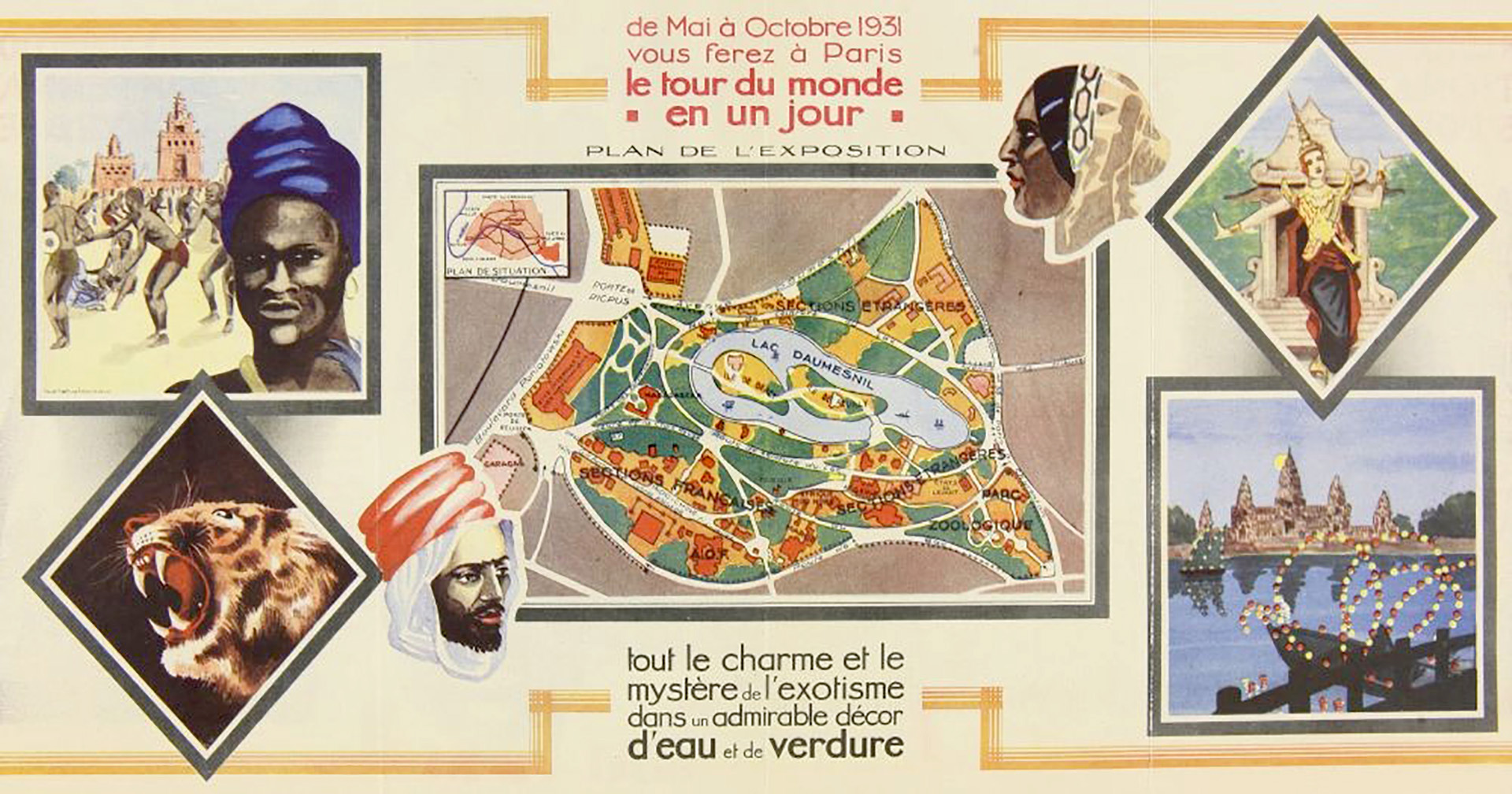

Advertisement of the Exposition coloniale internationale [International Colonial Exhibition], 1931

ephemera, exhibition print

Musée national de l’histoire de l’immigration, Paris

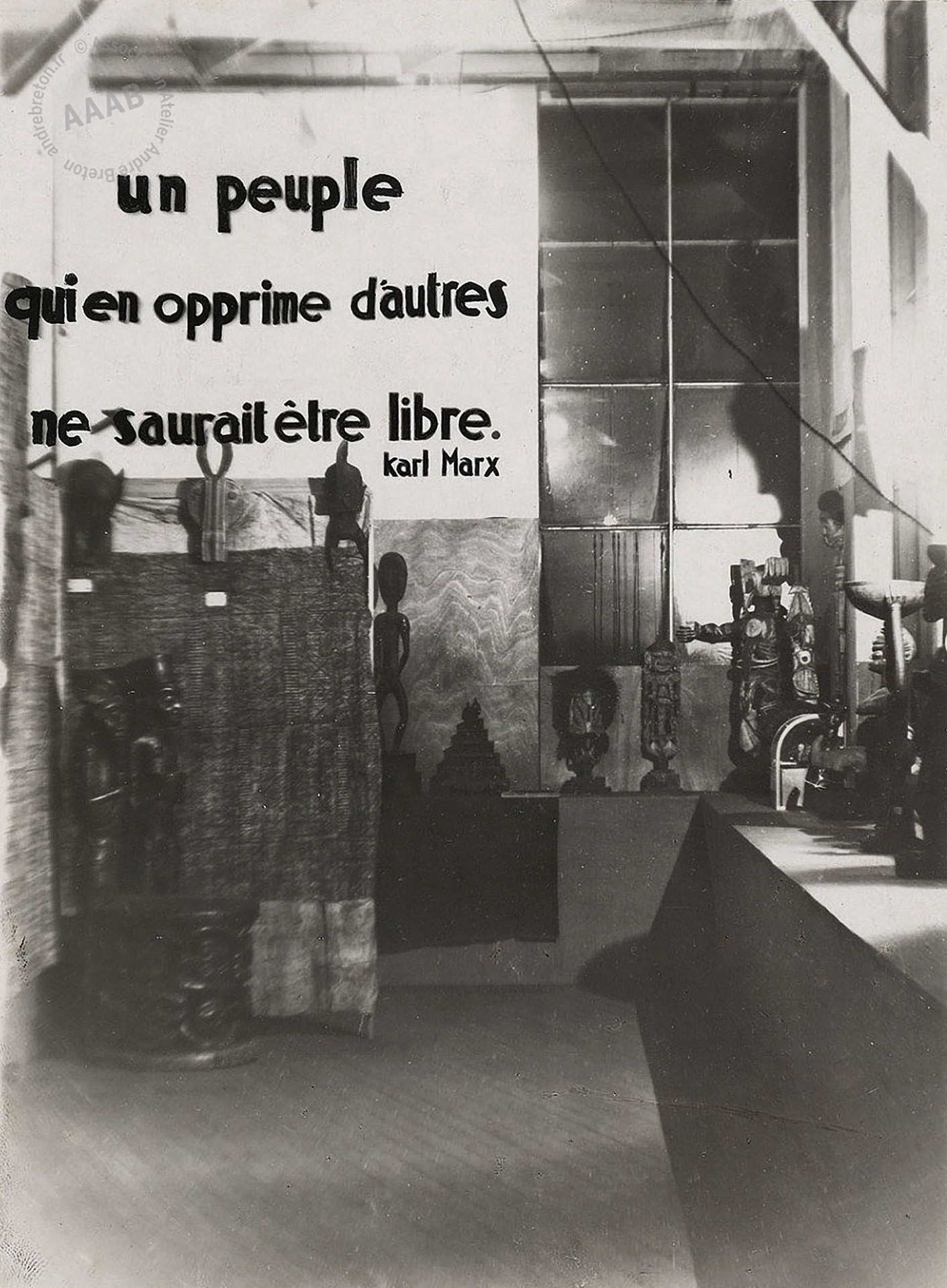

Interior of the exhibition La verité sur les colonies [The truth about the Colonies], 1931

bw. photo, exhibition print

Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles / Association Atelier André Breton, Paris

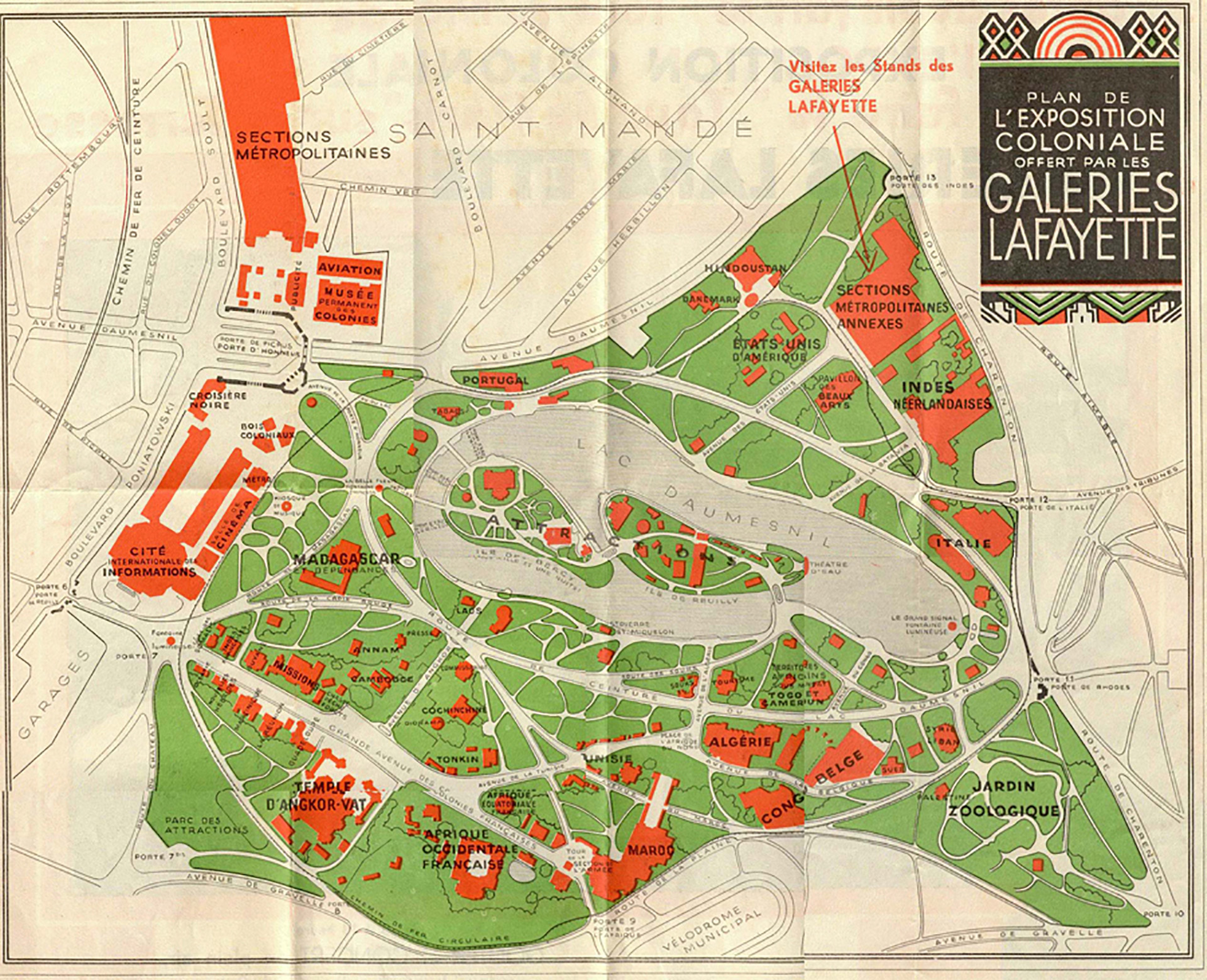

Inaugurated on May 6, 1931, the Exposition coloniale attempted to promote an image of Imperial France at the zenith of its power. Taking the form of an immense popular show, a veritable city within the city, the exposition stretched over 1,200 square meters, with 10 kilometers of sign-posted paths. It was part of the tradition of the Universal Expositions of the 19th century devoted to the promotion of the power of the European nations. Dedicated exclusively to the colonies, it took place from May to November 1931 and attracted almost 8 million visitors for 33 million tickets sold. The exhibition stretched from the Porte Dorée metro station (formerly Picpus) over the whole of the Bois de Vincennes. The Palace of the Colonies [Palais de la Porte Dorée, today’s Musée national de l’histoire de l’immigration], the only construction built to last after the event was over, comprised an overview of the exhibition, presenting the history of the French Empire, its territories, the colonies’ contributions to France, as well as those of France to the colonies.

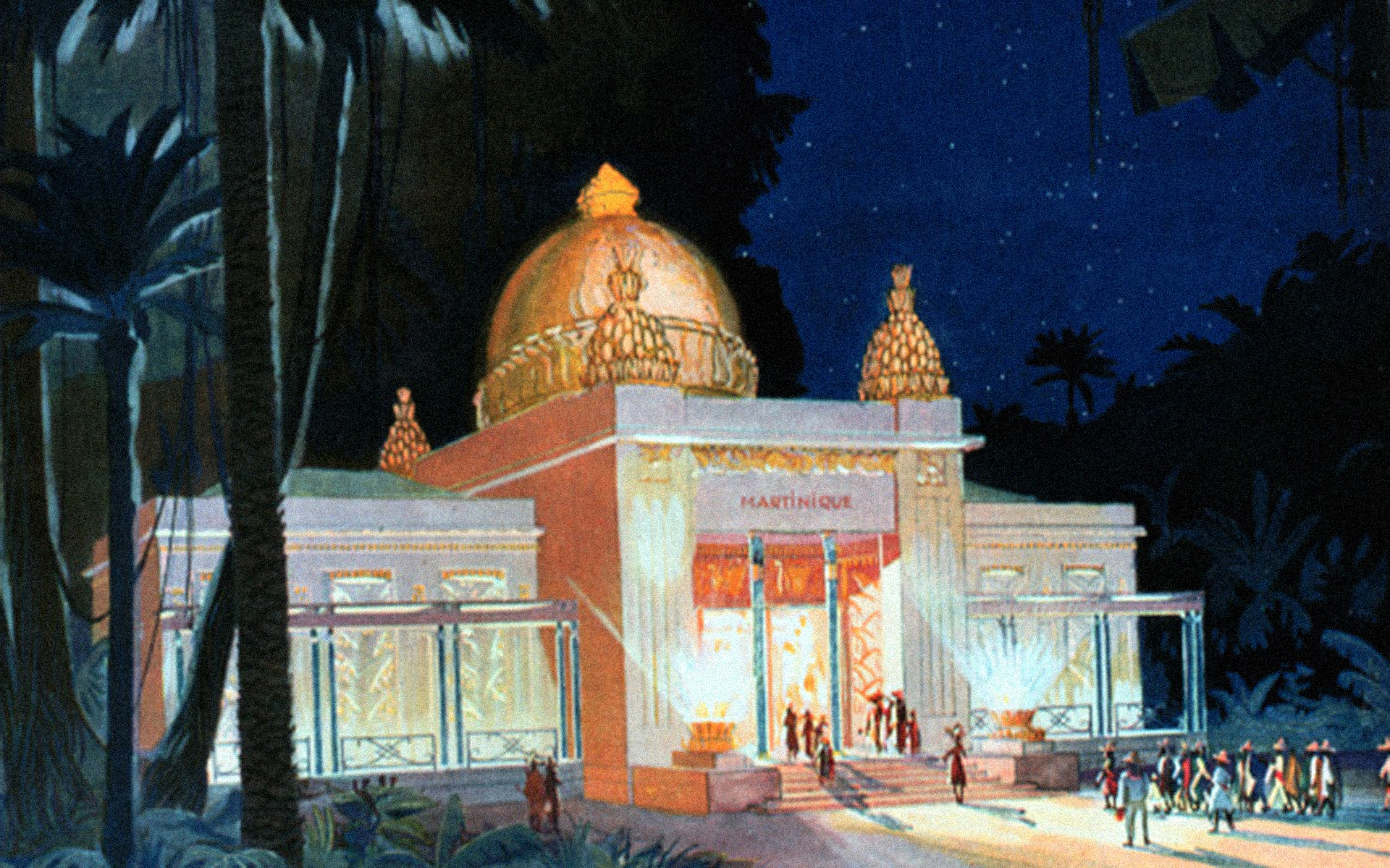

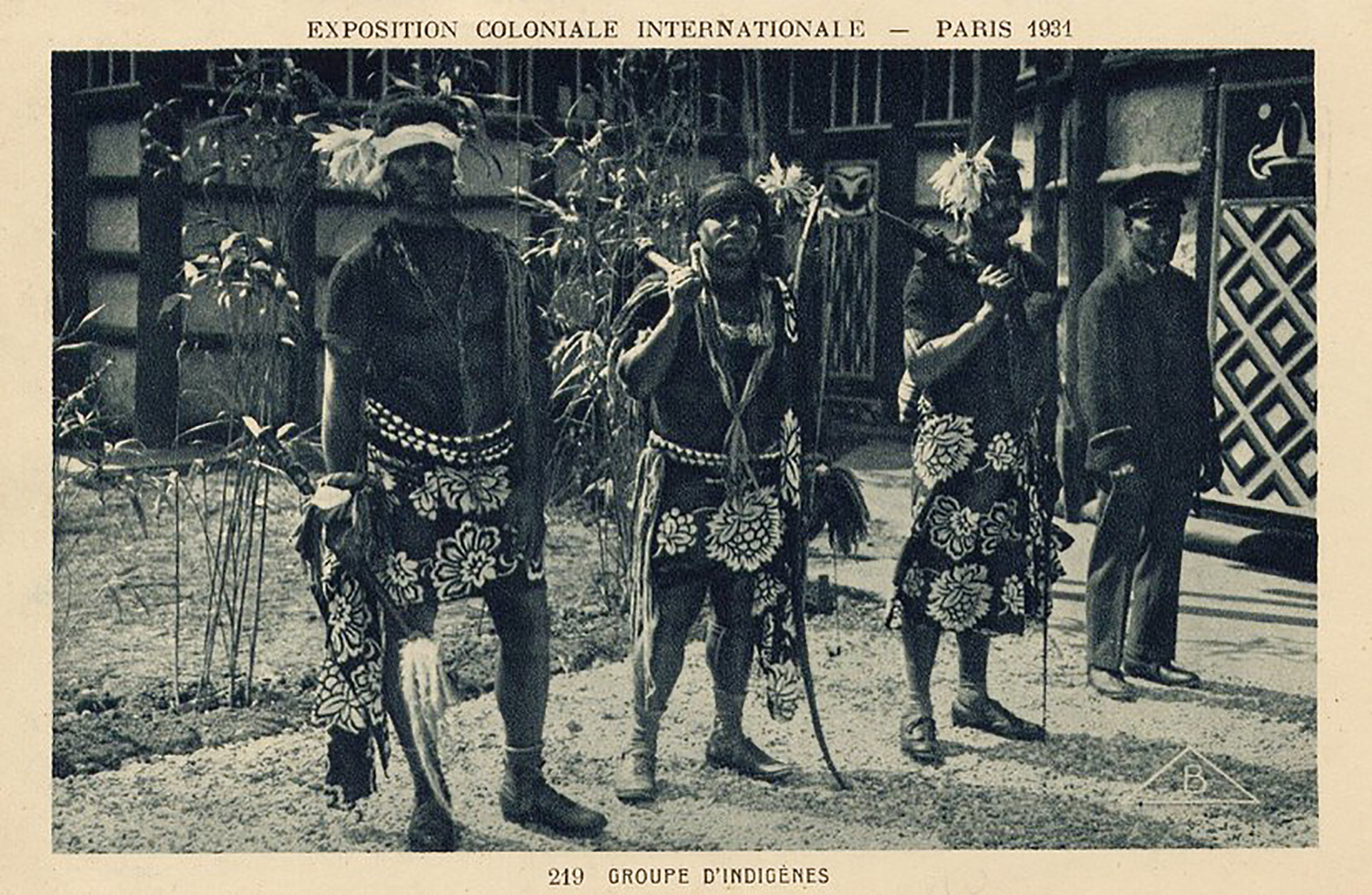

To head up the entire affair, the government appointed Le Maréchal Lyautey, a distinguished and experienced military man. Lyautey had been in charge of the Franco-Moroccan colonial exhibition held in Casablanca in 1915, and had definite ideas about how such an affair should be organized. He forbade “racist” displays; instead, the show was to accentuate “colonial humanism”. According to his plans, the exhibition aimed to give the French people the feeling of strolling through a country that was not limited to its continental borders. Invited to “take a trip around the world in one day”, the visitor could discover each of the French colonies inside pavilions inspired by native architecture. For example, Indochina was represented by a pavilion copying the spectacular dimensions of the Cambodian temple of Angkor Vat. The pavilion of French West Africa was inspired by the architecture of the great Djenné mosque in Mali. To enliven the event and make it even more attractive, various activities were proposed to the visitors. Dance performances were one of the most popular attractions. In each section, the inhabitants of the colonies animated these reconstituted villages. Artisans worked in front of the public and others kept souvenir stands. Even if the aim of the Exposition coloniale of 1931 was not to make fun of the colonized peoples, as was the case of former colonial exhibitions, it still meant exhibiting men and women to affirm France’s power over them.

The map of the Exposition coloniale, 1931

ephemera, exhibition print

Musée national de l’histoire de l’immigration, Paris

The Cambodia Pavilion at the Exposition coloniale, postcard, 1931

ephemera, exhibition print

Musée national de l’histoire de l’immigration, Paris

The Martinique Pavilion at the Exposition coloniale, postcard, 1931

ephemera, exhibition print

Musée national de l’histoire de l’immigration, Paris

The Orchestre Stellion of Martinique at the Exposition coloniale, 1931

bw. photo, exhibition print

Musée national de l’histoire de l’immigration, Paris

Even though the Exposition coloniale tried to show a more “human” face of colonialism, the shameful tradition of the “human zoos” was not forgotten either. In 1931 New Caledonian Kanaks left Noumea for Paris to take part in the Exposition coloniale. They considered themselves ambassadors but, after arriving in Marseille, they were directly brought in to the Jardin d’Acclimatation in Paris and put on display cast as “savage polygamists and cannibals.” They were forbidden to leave the “Kanak village”, although among the many unfulfilled promises, they were offered to visit the capital. It should be noted that most of them spoke French, had studied, and worked as typographers, teachers or customs employees. Some of them died because of the inadequate care. Under public pressure the French Colonial Minister prohibited the recruitment of individuals in the colonies and sent the surviving Kanaks back to New Caledonia “as soon as possible after their tour in Germany”. The “human zoo” phenomenon began to decline in the 1930s with changing public interest and the advent of cinema. The last “living spectacles” were Congo villagers exhibited in Belgium in 1958.

The Kanaks, Pavilion of New Caledonia at the Exposition coloniale, 1931

The photo was published in the brochure of the Exposition coloniale, exhibition print

Musée national de l’histoire de l’immigration, Paris

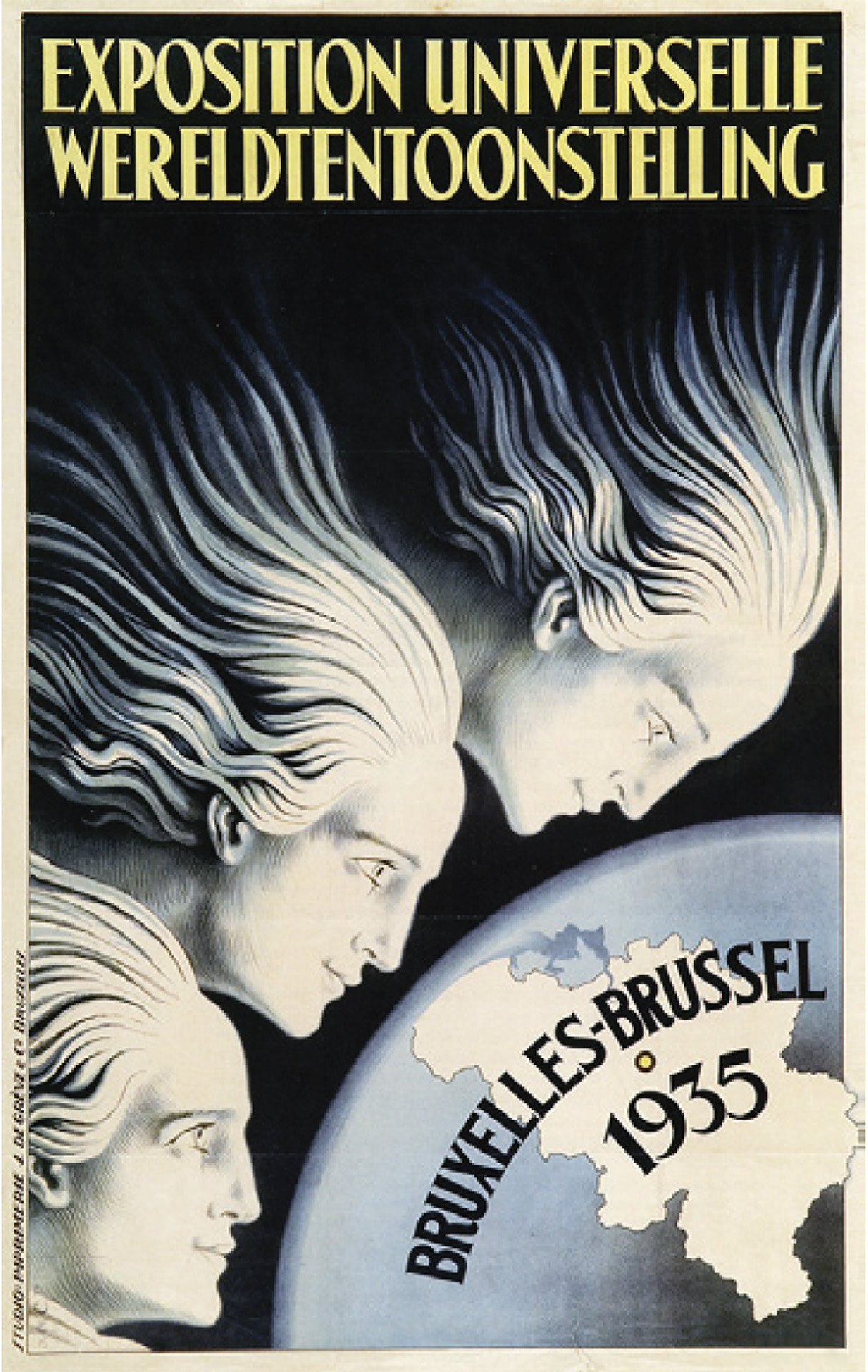

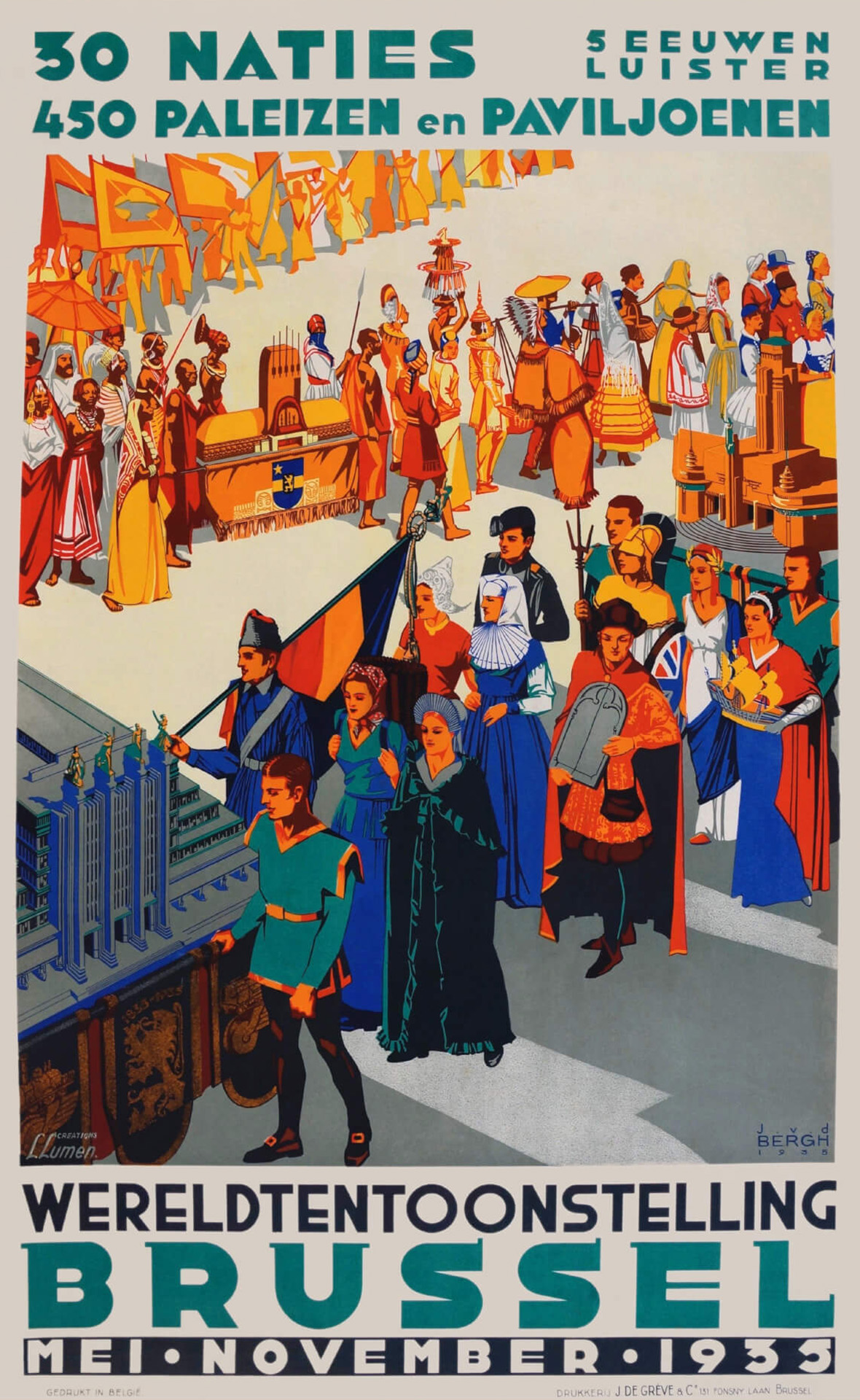

On the occasion of the Exposition Universelle, Brussels, despite the economic and political difficulties of the time, built a remarkable ephemeral city on the Heysel Plateau, three hundred acres of standard block buildings with limited charm, but amazing durability. The 1958 fair would be held on the same site, with an added Atomium. The exhibition attracted some twenty million visitors. Among many other contributors, Le Corbusier designed part of the French exhibit; and the Belgian art exposition prominently displayed the work of contemporary Belgian artists, including Paul Delvaux, René Magritte and Louis Van Lint, boosting their careers. Yet, the Exposition Universelle focused mainly on the colonial history of Belgium, as it was organized on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the founding of the “independent” state of the Belgian Congo [État indépendant du Congo, also known as Congo Free State]. The title of the exhibition, Paix entre les races [Peace between the races] was in sharp contrast with the presentation of Belgian Congo in this context. Between 1885 and 1908, the Congo Free State was privately owned by Leopold II of Belgium. Leopold’s reign in the Congo eventually earned infamy on account of the atrocities perpetrated on the locals, which led to one of the greatest international scandals of the early 20th century. The loss of life and atrocities inspired literature such as Joseph Conrad’s novel Heart of Darkness and raised an international outcry. By 1908, public pressure and diplomatic maneuvers led to the end of Leopold II’s absolutist rule and to the annexation of the Congo Free State as a colony of Belgium. It became known thereafter as the Belgian Congo. The exhibition Paix entre les races thus celebrated one of the saddest chapters in colonial history.

Poster of the Exposition Universelle [Universal and International exhibition] in Brussels, 1935

poster, exhibition print

Wikimedia commons

Poster of the Exposition Universelle [Universal and International exhibition] in Brussels, 1935

poster, exhibition print

Wikimedia commons

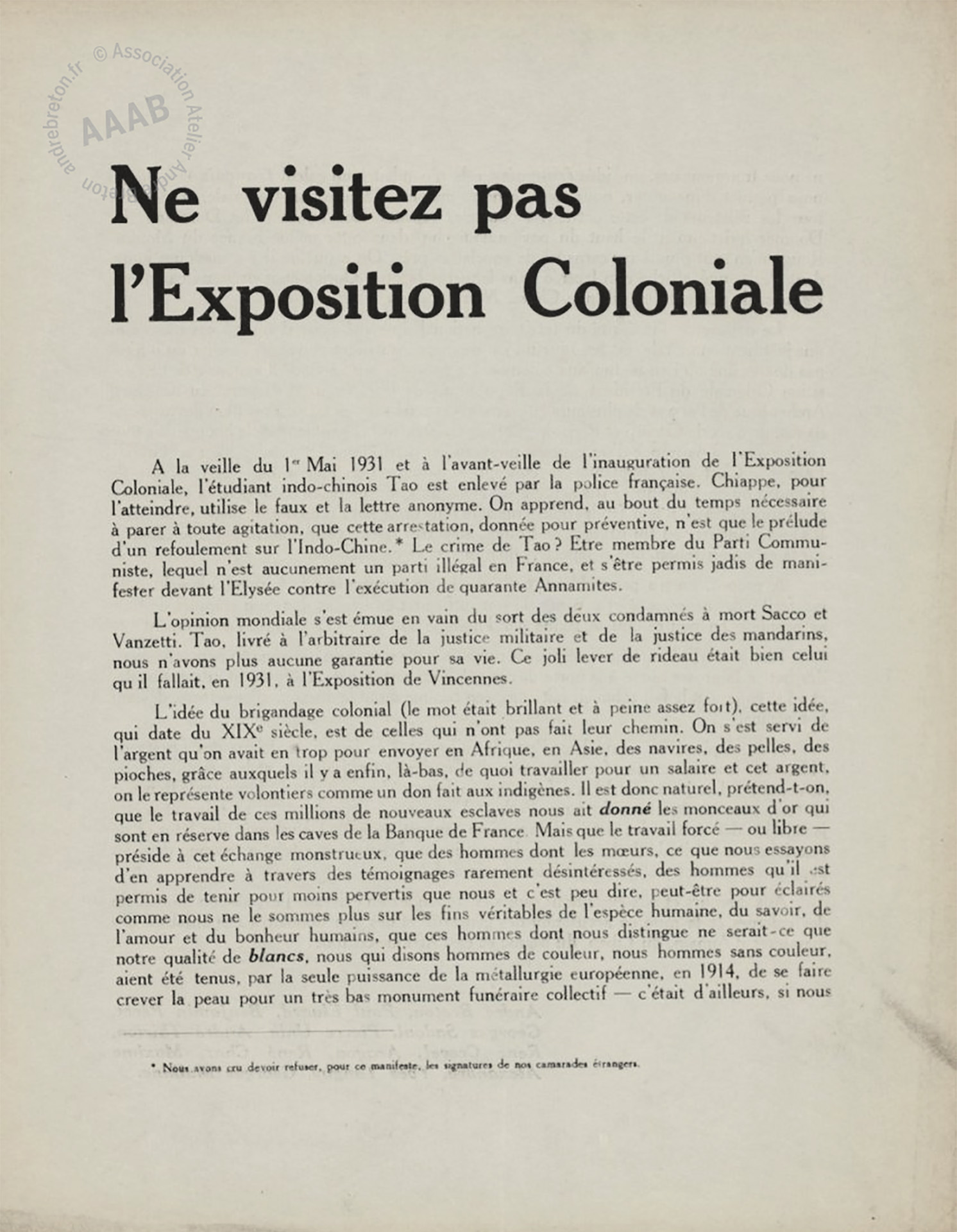

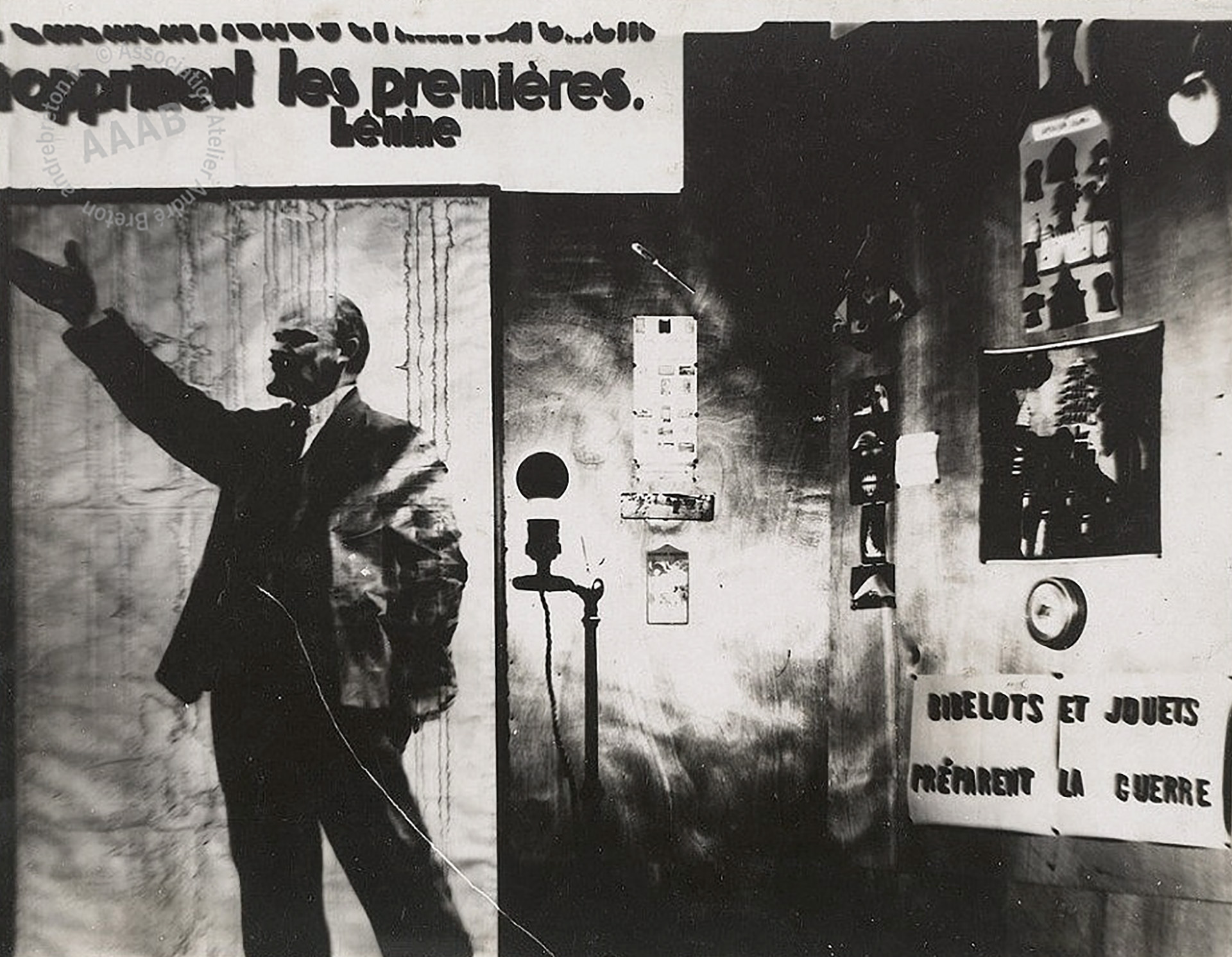

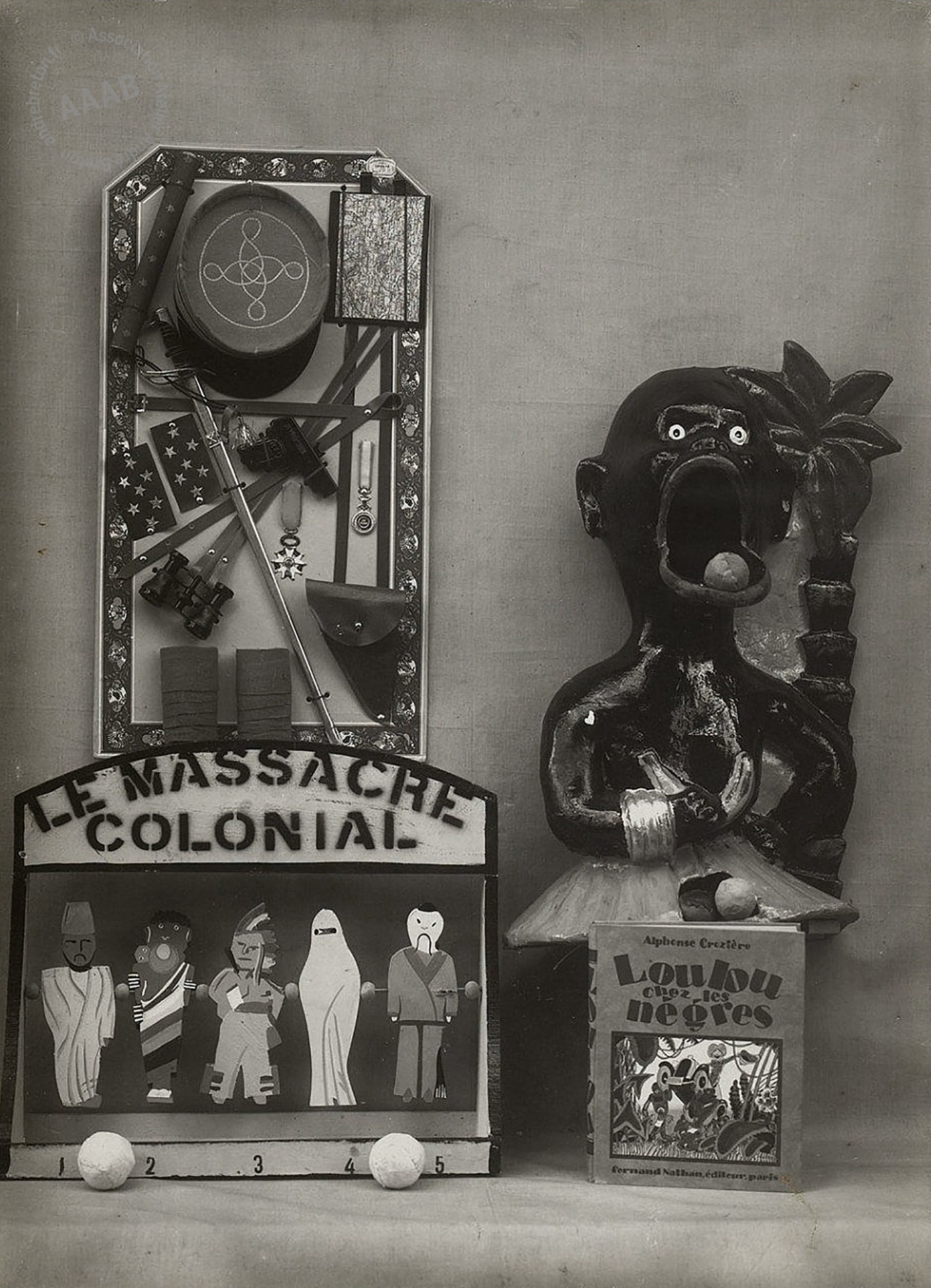

In 1931, French Surrealists, in conjunction with the communist Ligue anti-impérialiste and the French Communist Party (PCF), mounted a protest against the Exposition international coloniale by staging an anti-colonial exhibition La vérité sur les colonies [The Truth about the Colonies]. The surrealists also distributed their pamphlet Ne visitez pas l’Exposition Coloniale [Don’t Visit the Colonial Exhibition!] on the streets of Paris. The exhibition was held in a large building on Place Fabien that had served as headquarters for the Communist Party’s central committee. The aim of the exposition was to subvert the paradigms established by the official exhibition by showing the most repressive and brutal aspects of colonialism. It was intended to show the unconcealed truth: “The outrageous crimes committed by the colonial sharks, the regime of slavery imposed upon the workers in the colonies.” In the so-called “Hall of Fetishes,” one vitrine was imitating the museological representation of other cultures; it presented “European fetishes” and Catholic propaganda, deconstructing the “belief in fetishes” as a feature of difference and superiority. In some way, the installations perpetuated the colonial representational forms of the exhibition it criticized, since they took the objects of indigenous cultures out of their original contexts, and utilized them as illustrations of their ideological-political agenda. Nevertheless, the surrealists’ intention to unmask the crimes of the colonialist powers can be interpreted as a genuine conviction. After all, it was Breton and his circle that prompted the advent of such movements like the Négritude movement or Afro-surrealism.

André Breton, Paul Éluard et al., “Ne visitez pas l’Exposition Coloniale” [Do not visit the Colonial Exhibition], 1931

leaflet, exhibition print

courtesy of the Association Atelier André Breton, Paris

Interior of the exhibition La verité sur les colonies [The truth about the Colonies], 1931

4 bw. photos, exhibition prints

Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles / Association Atelier André Breton, Paris

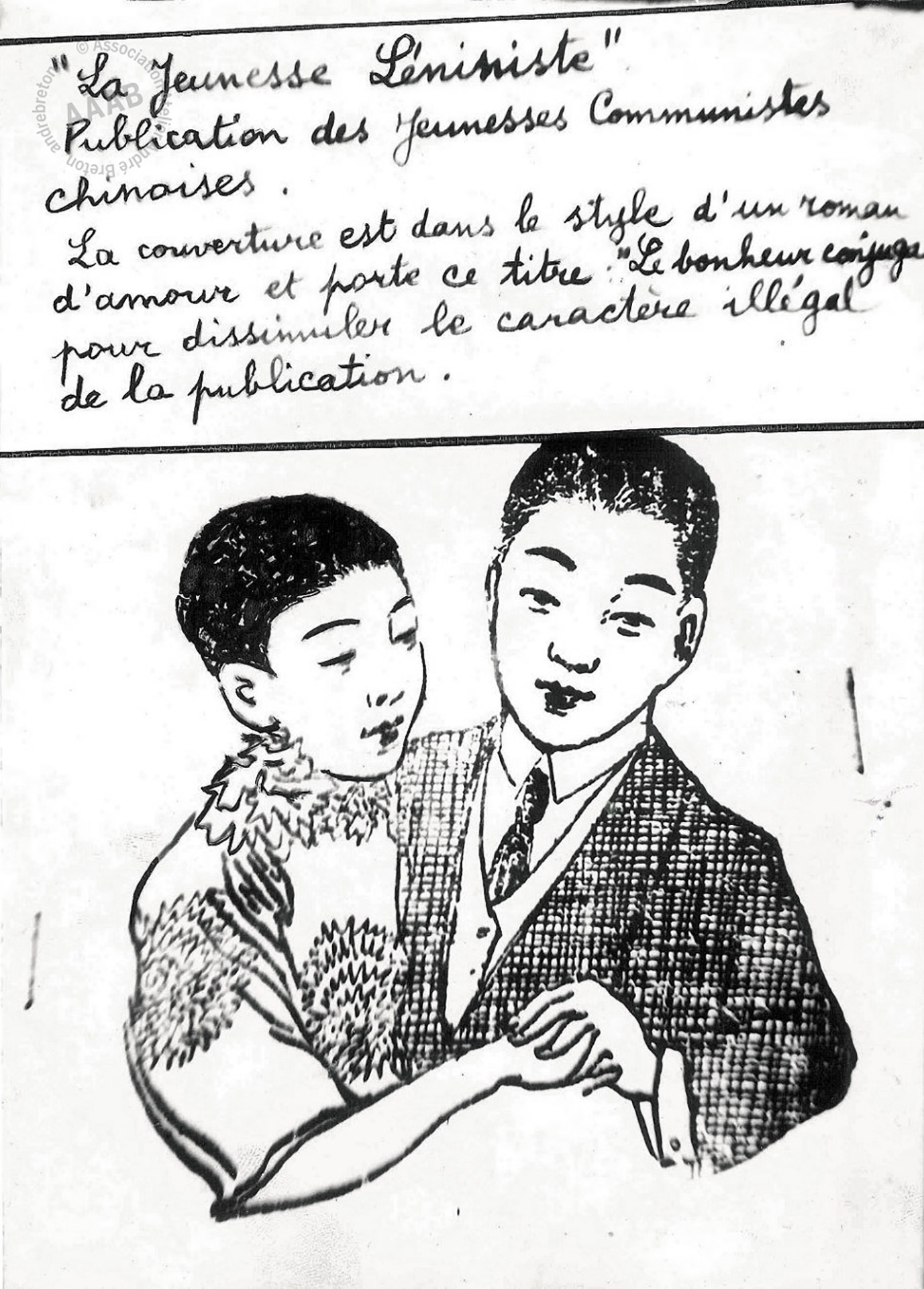

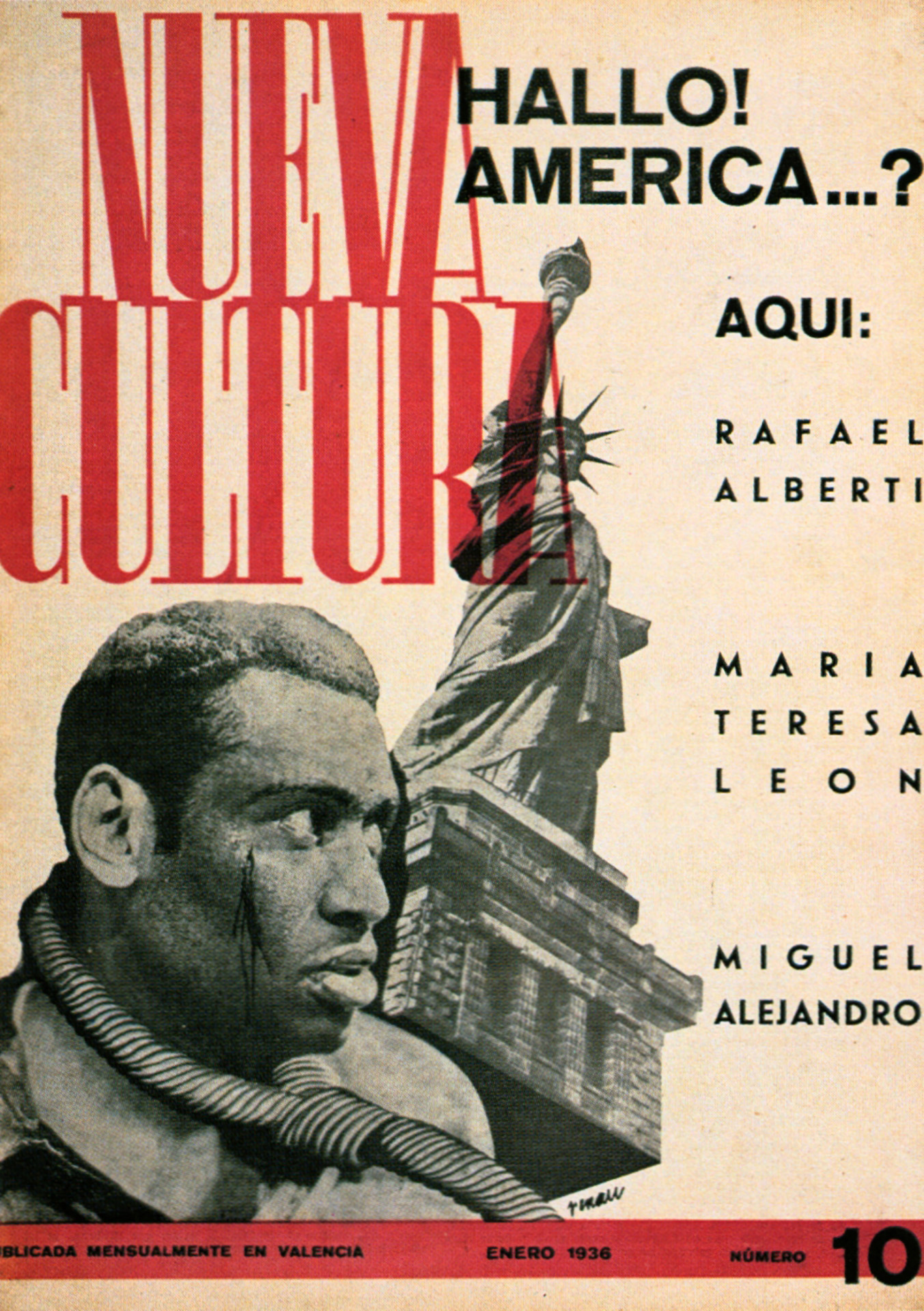

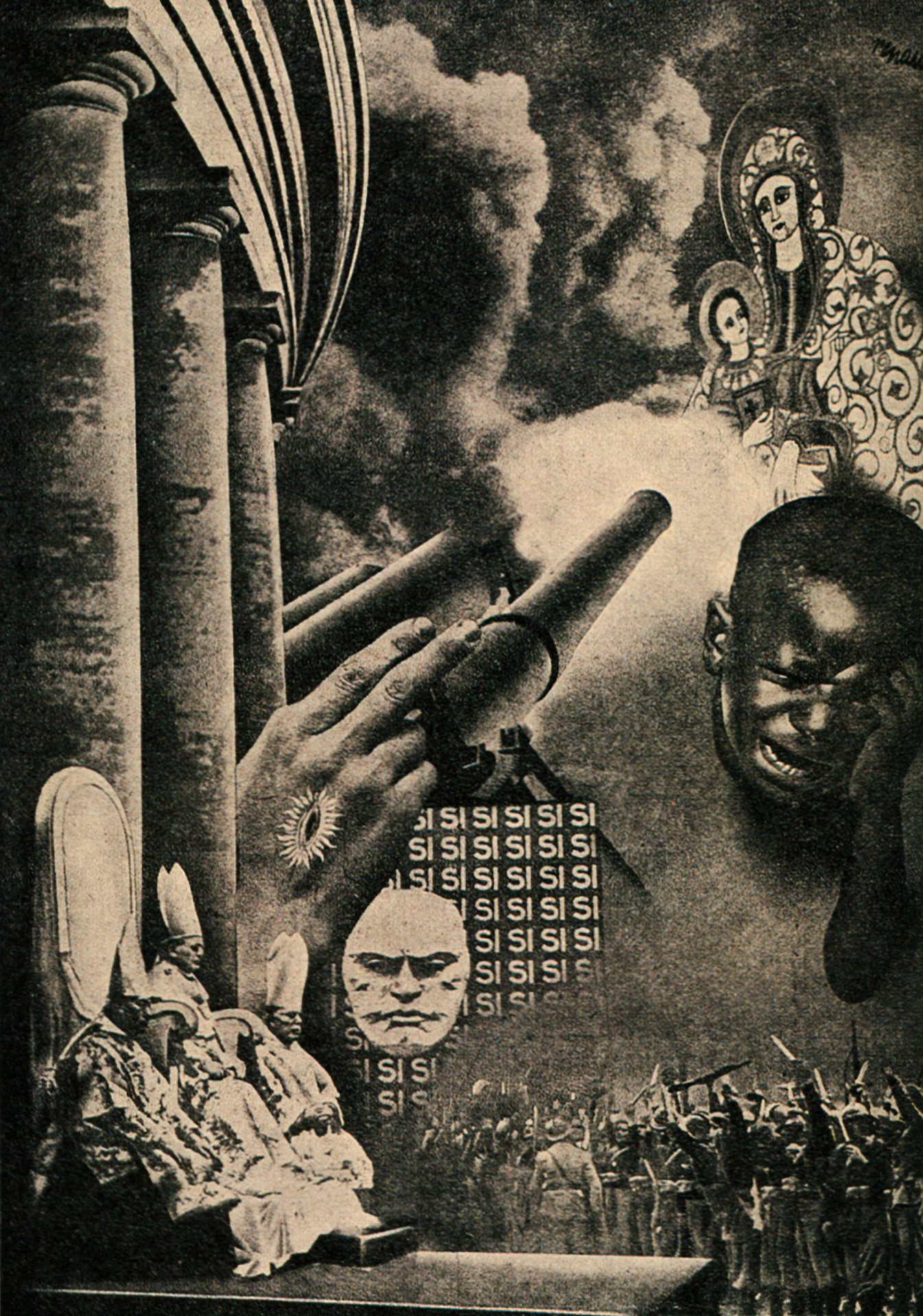

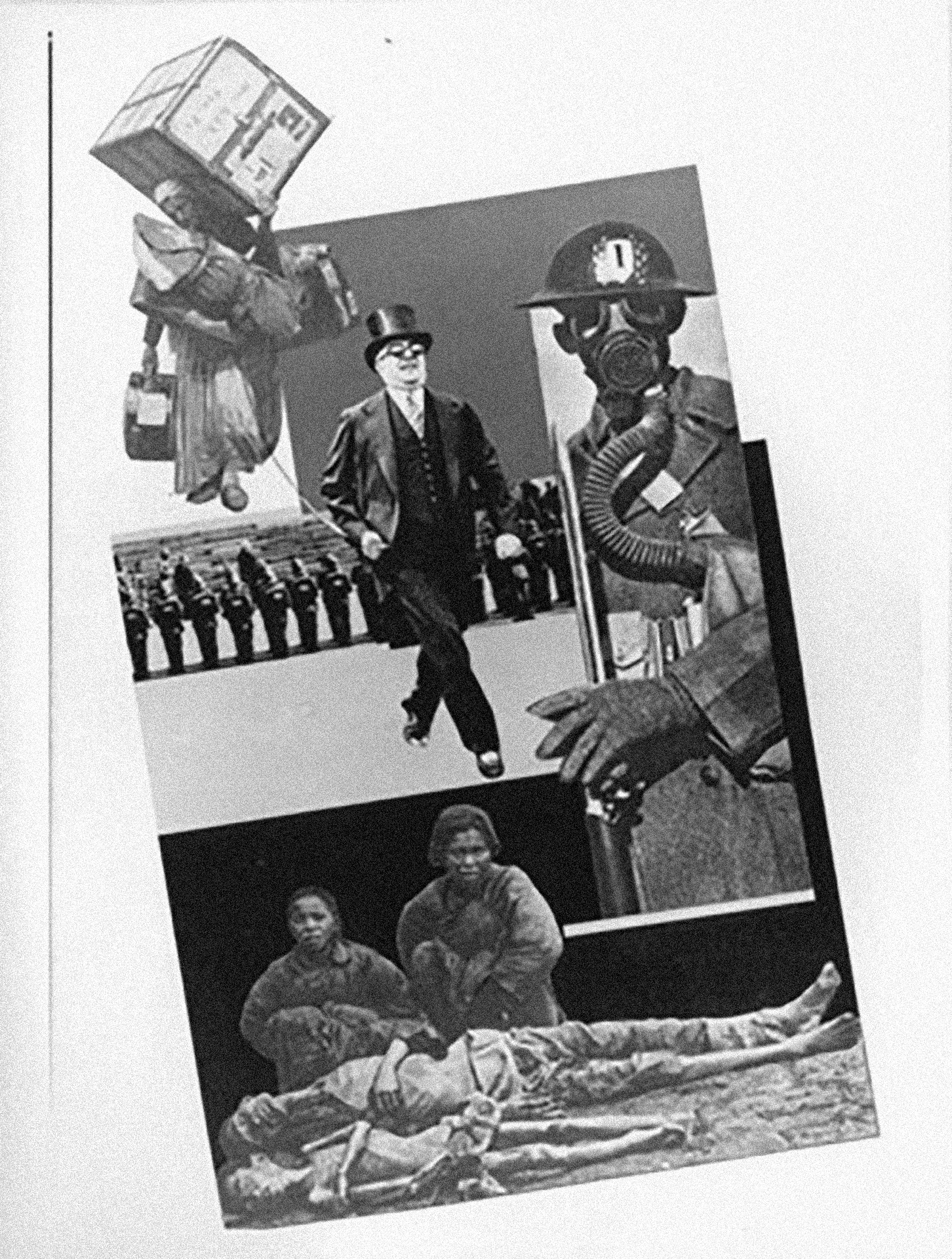

Josep Renau, one of the exhibitors of the Spanish Pavilion of 1937 in Paris, also addressed the issue of colonialism in his photomontages. In the series Páginas negras de guerra [Black Pages of War, 1933], as well as in the series Testigos Negros de nuestro tiempo [Black Witnesses of our Time, 1935–1937] that he created for the magazine Nueva Cultura [New Culture] he followed the iconography of Soviet caricatures, depicting Afro-American people as victims of American capitalism. Similar to the exhibition La verité sur le colonies, the montages make use of the images of people of color, utilizing them in the service of an ideology. Yet, as in the case of the surrealists, Renau’s sentiments in relation to the oppressed was genuine. He considered racism as universal as human suffering, against both he tried to fight both as a devoted Communist and as an artist.

Josep Renau, Cover of the magazine Nueva Cultura [New Culture], October 1936

exhibition print

IVAM, Instituto Valenciano de Arte Moderno, Valencia

Josep Renau, Photomontage from the series Testigos Negros de nuestro tiempo [Black Witnesses of our Time], 1936

published in the magazine Nueva Cultura [New Culture], October 1936

photomontage, exhibition print

IVAM, Instituto Valenciano de Arte Moderno, Valencia

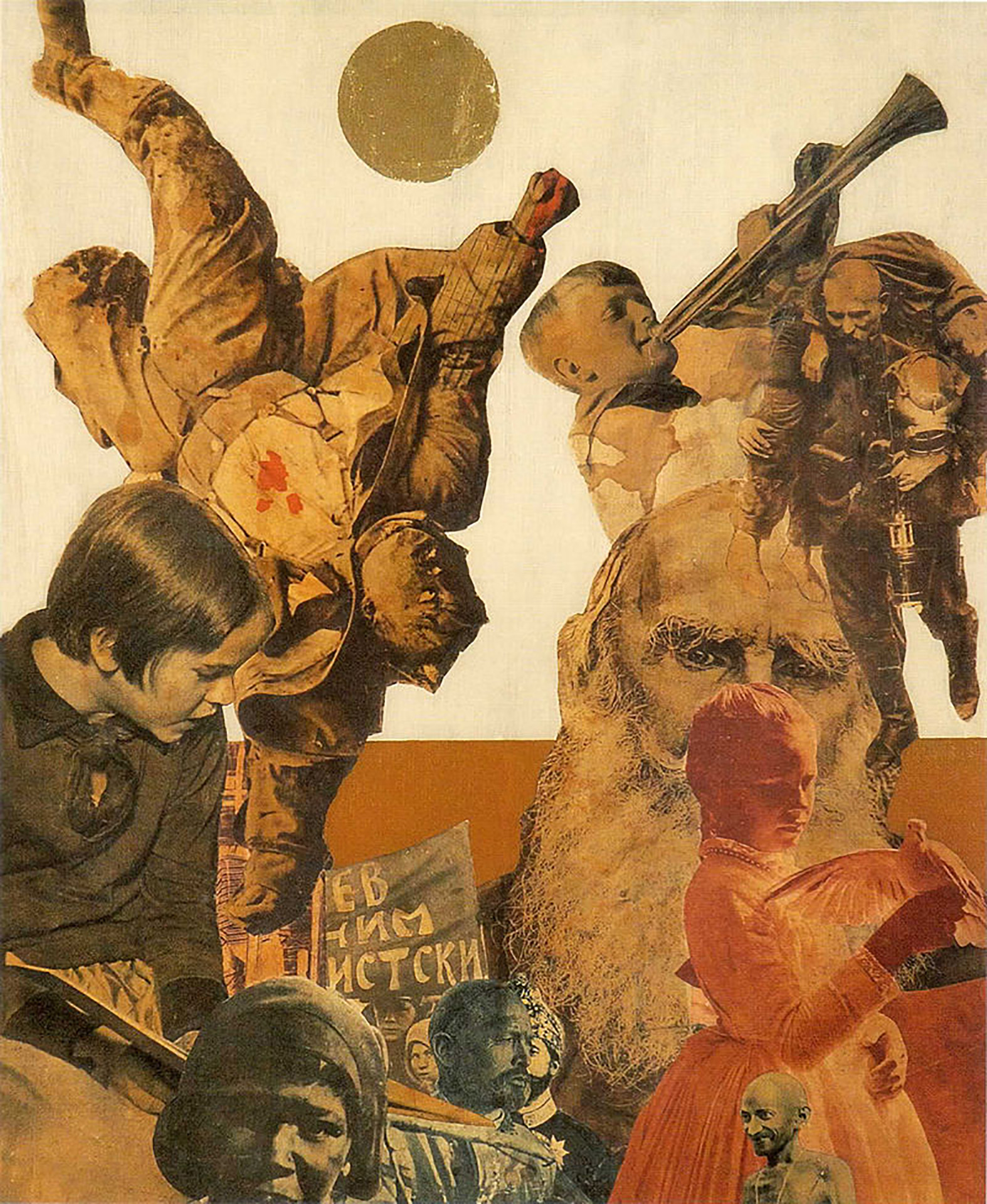

Although Hungary did not have colonies, the critique of colonial politics also appeared in the work of several Hungarian artists. During his years in Paris between 1930 and 1934, Lajos Vajda was a regular visitor to the Ethnographic Museum [Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro], where he attended lectures on the cultures of Oceanic, Indian and African peoples. Some of his montages made at this time, inspired by both constructivism and surrealism, are about the injustices of the world, such as Tolsztoj és Gandhi [Tolstoy and Gandhi], or A megkorbácsolt hátú [The Whipped One]. Vajda’s interest was not limited to Europe, he was deeply concerned with the global injustice of the whole world. Like Vajda, the Hungarian constructivist Lajos Lengyel, a member of Lajos Kassák’s Munka [Work] Circle, made a number of photomontages in which he depicted not only the problems of Hungarian society, but also their wider, international context.

Lajos Vajda, A megkorbácsolt hátú [The Whipped One], 1930–1933

fotómontázs, kiállítási nyomat

Ferenc Kiss Collection, Budapest

Lajos Vajda, Tolsztoj és Gandhi [Tolstoy and Gandhi], 1930–1933

fotómontázs, kiállítási nyomat

Ferenc Kiss Collection, Budapest

József Lengyel, Gyarmati politika [Colonial Politics], 1935

photomontage, exhibition print

Hungarian Museum of Photography, Kecskemét / courtesy of János Lengyel

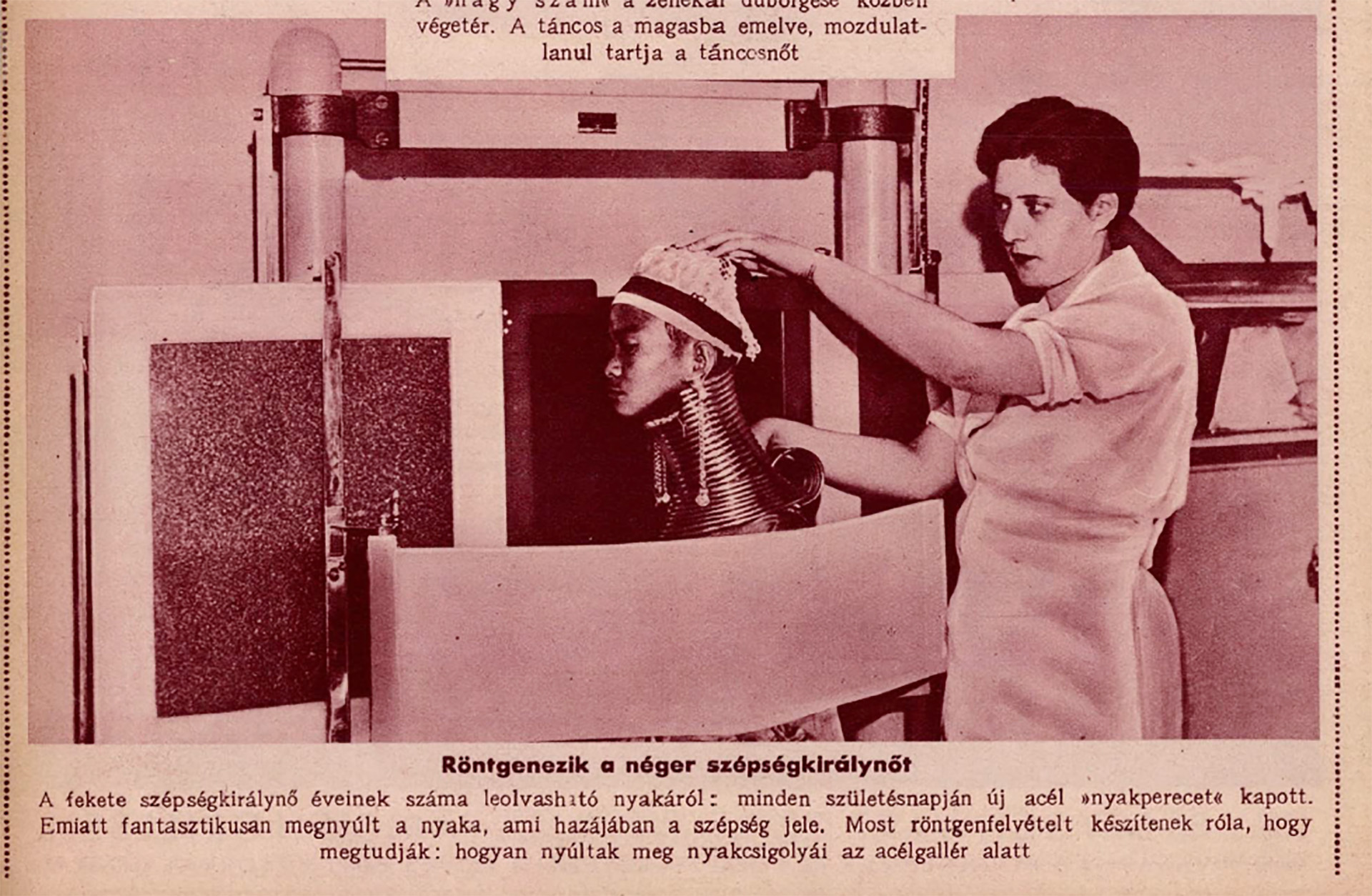

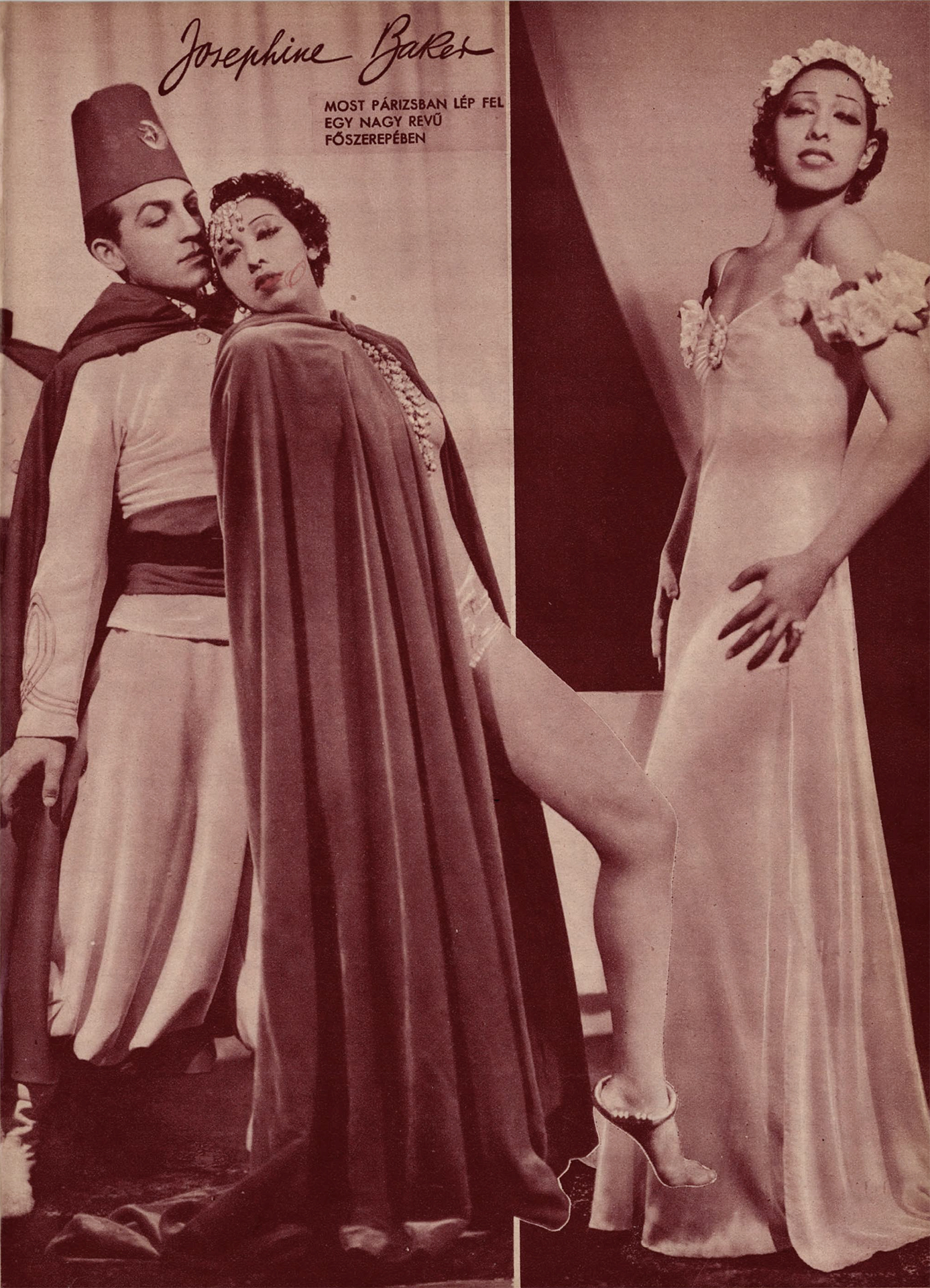

In Hungary, however, it was typically not the critique of colonial politics that was the subject when it came to portraying people “from faraway and foreign lands” (i.e. people of color). Due to the relative unfamiliarity and distance of colonial culture, the media mainly featured exoticized portrayals of these people, or international celebrities of color who also participated in the entertainment industry along the lines of exoticism.

“The Negro beauty queen is x-rayed,” 1934

exhibition print

Pesti Napló Képes Melléklete [Illustrated Supplement of Pesti Napló], January 28, 1936 / Arcanum

Josephine Baker in Paris, 1936

exhibition print

Pesti Napló Képes Melléklete [Illustrated Supplement of Pesti Napló], November 18, 1936 / Arcanum