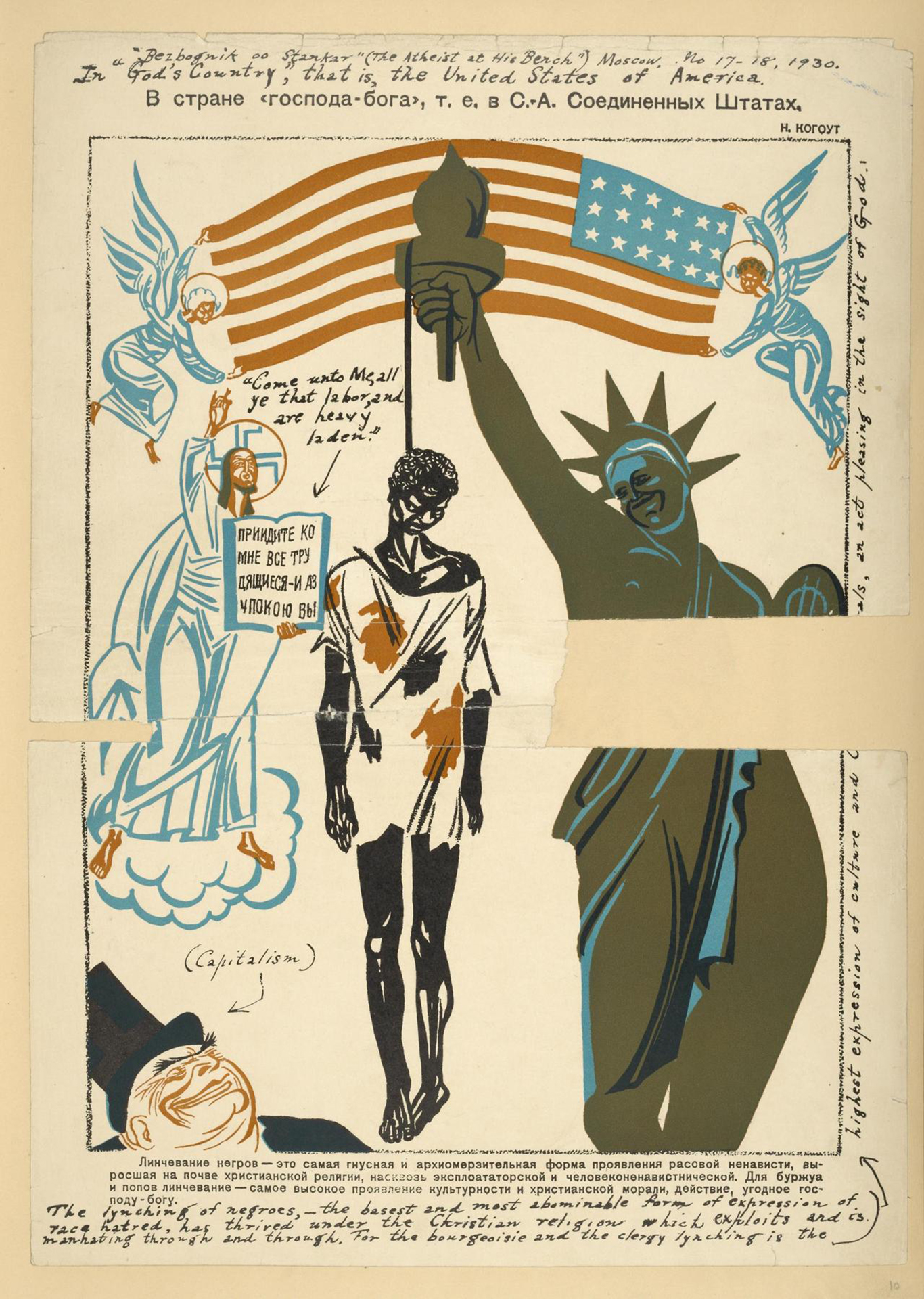

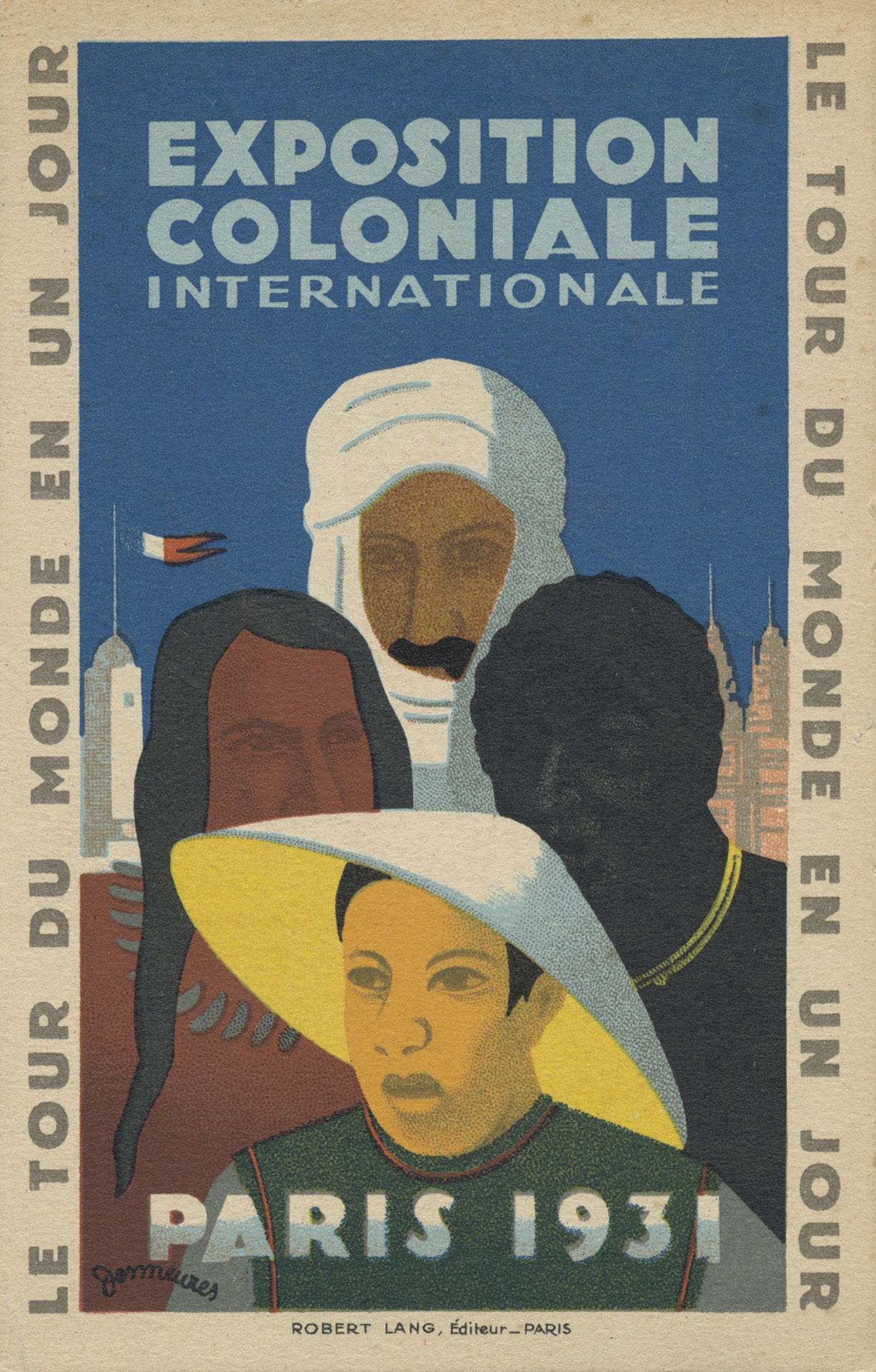

The left-wing intelligentsia of the interwar years not only wanted to fight Fascism in Europe but were also against all forms of oppression, including that practiced by their own countries in the colonies. Anti-colonialist sentiment had been galvanized not only by the impact of the First World War, the Russian Revolution and the rapid advance of nationalist-populist movements, but also by such shocking instances of imperial violence as the Amritsar massacre in 1919, the shooting of Chinese protestors in Shanghai in 1925 and the French suppression of the Syrian revolt of 1925–27. Several solidarity campaigns were launched that included the “Hands off China” campaign of the mid-1920s in Britain and Germany, or a solidarity campaign prompted by the Meerut conspiracy trial of British and Indian trade unionists (1929–33). A number of influential organizations were set up in the late 1920s with the intention of channeling such sympathy into effective political action. In particular, the transnational League Against Imperialism and Colonial Oppression (LAI, Liga gegen Kolonialgreuel und Unterdrückung, Ligue contre l’impérialisme et l’oppression coloniale] was established in Berlin following a successful founding congress in Brussels in February 1927. The Communist-inspired LAI was only one of these organizations that challenged the status quo, others included the London-based India League, and the Ligue de Défense de la race Nègre [League for the Defense of the Negro Race], which was formed in France in May 1927. Almost all of these organizations had strong Communist support. Of course, the extent and cohesiveness of the anti-imperialist movements of this period should not be exaggerated. The Comintern’s radical anti-imperialist policies during the “Third Period” (1927–33) were accompanied by a highly sectarian and counterproductive attitude towards middle-class nationalist movements in the colonial world. Furthermore, it was apparent that Comintern’s concept of anti-imperialism was more about the fight against the capitalist world, especially, the United States, than it was about solidarity with the oppressed nations and peoples of the Global South. In a way, Communists also instrumentalized the topic of the colonies and the people oppressed by the colonialist powers the same way they were instrumentalized at such events as the Exposition coloniale internationale [International Colonial Exhibition] of 1931 in Paris, or the World Fair in Brussels in 1935 [Exposition Universelle et Internationale Bruxelles de 1935], which, despite its title Paix entre les races [Peace between the Races], happened to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the founding of the “independent” state of the Belgian Congo [État indépendant du Congo]. T. Ras Makonnen, one of the leading international black activists of the period, developed a burning animosity at this time towards the Communists and, indeed, all political movements not under black leadership.

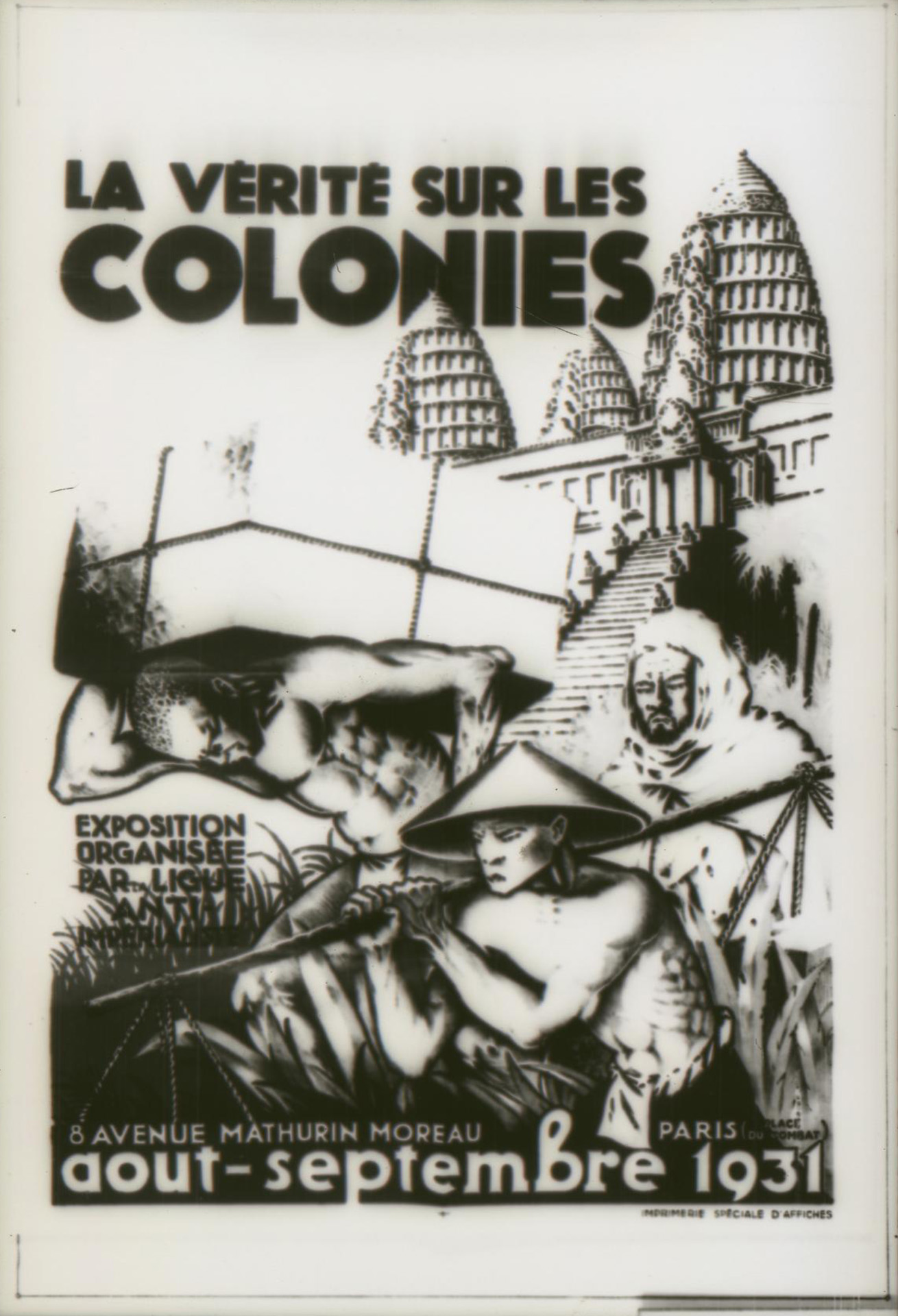

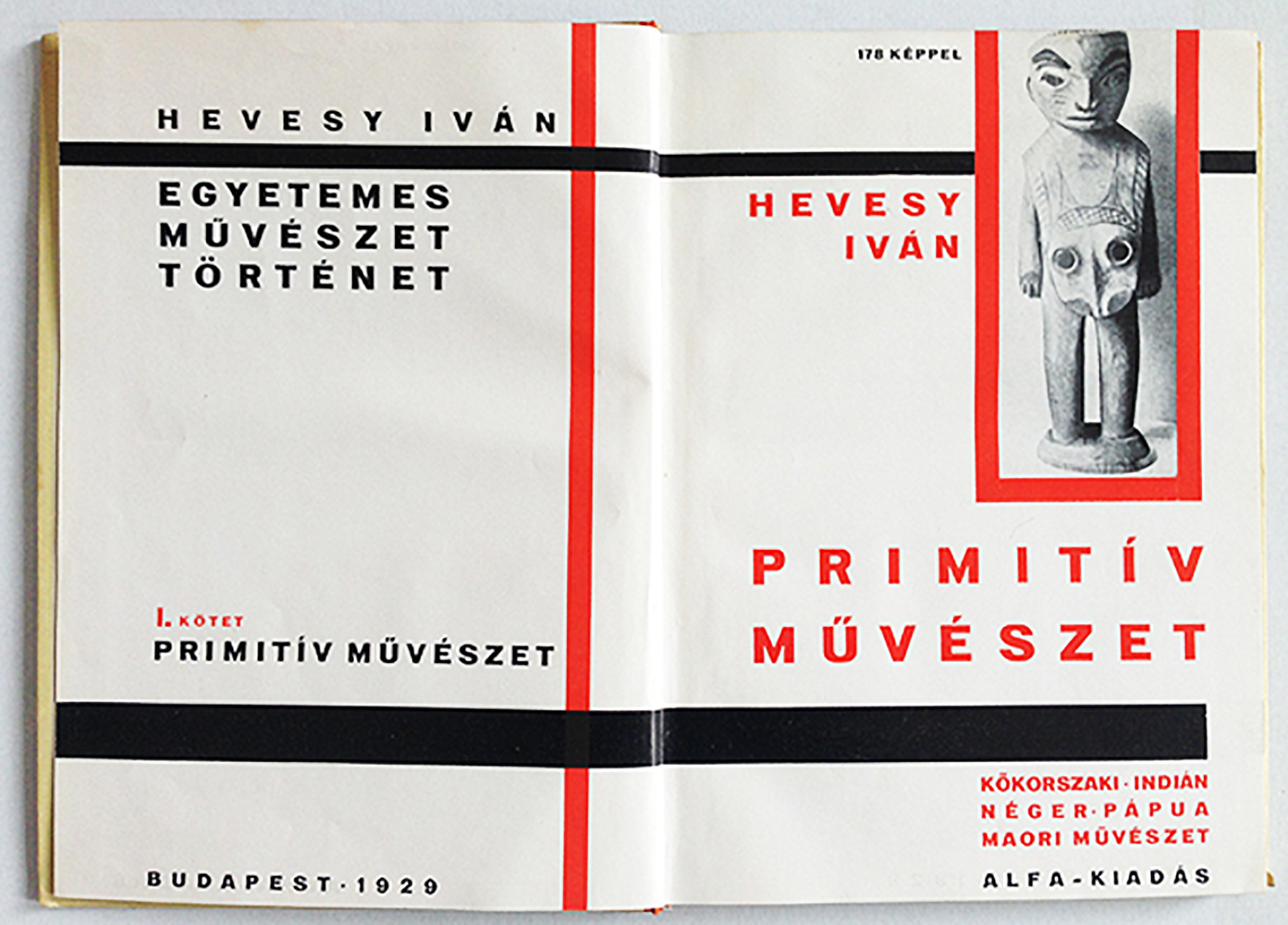

The French Communist and the League Against Imperialism and Colonial Oppression organized the exhibition La vérité sur les colonies [The Truth about the Colonies] as a counter-exhibition to the Exposition coloniale, in which many surrealist artists also participated. While the exhibition eschewed all primitivist stereotypes, it had no qualms about taking indigenous objects out of context and in the interests of Communist propaganda, instrumentalizing them for purely ideological ends. Yet, the mid-1930s was also the period of the beginning of the Négritude movement in France and French-speaking colonies. To a certain extent, the movement came to the fore as a response to the concept of “Primitivism,” which became a buzzword in the circles of modernist artists and theoreticians, and which, in a way, was another form of misrecognition of the cultures from outside of Europe. In the formation of the Négritude movement the Harlem Renaissance also played a pivotal role: there was an intense transatlantic exchange between members of the Harlem Renaissance and artists, writers, and intellectuals from the French colonies who gathered in Paris. In Hungary, seeing that the country had no colonies, these voices were barely heard. Instead, “primitive art” became a source of inspiration for modernist artists and poets, as can be gleaned from the book written by Iván Hevesy, the versatile Hungarian art historian, which was designed by Sándor Bortnyik, one of the most important figures of the Hungarian avant-garde.

Caricature of American Capitalism in Безбожник [The Godless] illustrated magazine, published by the Centre Soviet and Moscow Oblast Soviet of the Союз Воинствующих Безбожников [League of the Militant Godless], 1930

exhibition print

wikimedia commons

Poster of the exhibition Exposition coloniale internationale [International Colonial Exhibition], 1931

poster, exhibition print

Musée national de l’histoire de l’immigration, Paris

Poster of the exhibition La vérité sur les colonies [The Truth about the Colonies], 1931

poster, exhibition print

Musée national des Arts d’Afrique et d’Océanie, Paris

Iván Hevesy, Primitív művészet [Primitive Art], 1929

design by: Sándor Bortnyik, Budapest: Alfa

Budapest Poster Gallery